A Workers’ Revolution

However, this did not mean that the Russian Revolution would be confined to a liberal or bourgeois framework. Much like Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik current — and in direct opposition to their Menshevik rivals — Luxemburg held that the immediate task facing revolutionaries in the Russian Empire was the formation of a democratic republic under the control of the working class. Since the liberal bourgeoise was too weak and compromised to lead the revolution, “the proletariat had to become the only fighter and defender of the democratic forms of a bourgeois state”.

She stressed that conditions in Russia today were not like those existing in nineteenth-century France:

The Russian proletariat fights first for bourgeois freedom, for universal suffrage, the republic, the law of associations, freedom of the press, etc., but it does not fight with the illusions that filled the [French] proletariat of 1848. It fights for [such] liberties in order to instrumentalize them as a weapon against the bourgeoisie.

She further expanded on this point elsewhere:

The bourgeois revolution in Russia and Poland is not the work of the bourgeoisie, as in Germany and France in days gone by, but the working class, and a class already highly conscious of its labour interests at that — a working class that seeks political freedoms not so that the bourgeoisie may benefit, but just the opposite, so that the working class may resolve its class struggle with the bourgeoisie and thereby hasten the victory of socialism. That is why the current revolution is simultaneously a workers’ revolution. That is also why, in this revolution, the battle against absolutism goes hand in hand — must go hand in hand — with the battle against capital, with exploitation. And why economic strikes are in fact quite nearly inseparable in this revolution from political strikes.

Luxemburg consistently upheld the need for majority support from the exploited masses in achieving any transition to socialism, including those pertaining to freedom struggles in the technologically developed capitalist lands. As she later wrote in December 1918, on behalf of the group she led during the German Revolution: “The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power except in response to the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian mass of all of Germany, never except by the proletariat’s conscious affirmation of the views, aims, and methods of struggle of the Spartacus League.”

One Step Forward

Luxemburg’s perspective on the 1905 Russian Revolution raises a host of questions, which relate to the problems faced by revolutionary regimes in the non-Western world in the decades following her death. How can the working class maintain power in a democratic republic after the overthrow of the old regime if it represents only a minority of the populace? How can it do so if, as she claims, “Social Democracy finds only the autonomous class politics of the proletariat to be reliable” — since the hunger of the peasants for landed private property presumably puts them at odds with it? And how is it possible for such a democratic republic under the control of the proletariat to be sustained if revolutions do not occur in other countries that can come to its aid?

Luxemburg addressed these questions in a remarkable essay written in Polish in 1908, “Lessons of the Three Dumas,” which has never previously appeared in English. By 1908, the situation in Russia had radically changed since the revolution was by then defeated. She surveyed the course of its development, encouraging Marxists to “redouble their commitment to subjecting every detail of their tactics to rigorous self-criticism.” She did so by evaluating the history of the three Dumas — the parliamentary bodies established in the Russian Empire from 1906 as a concession to the revolution, with a restricted franchise that became progressively more biased in favour of the upper classes:

The Third Duma has shown — and from this flow its enormous political significance — that a parliamentary system that has not first overthrown the government, that has not achieved political power through revolution, not only cannot defeat the old power (a belief the First Duma vainly held), not only cannot hold its own against that power as an instrument of opposition (as the Second Duma tried to do), but can and must become, on the contrary, an instrument of the counterrevolution.

She proceeded to look ahead in thinking about the possible fate of a future revolution that, unlike the one in 1905, did succeed in overthrowing the old regime:

If the revolutionary proletariat in Russia were to gain political power, however temporarily, that would provide enormous encouragement to the international class struggle. That is why the working class in Poland and in Russia can and must strive to seize power with full consciousness. Because once workers have power, they can not only carry out the tasks of the current revolution directly — realizing political freedom across the Russian state — but also establish the eight-hour workday, upend agrarian relations, and in a word, materialize every aspect of their program, delivering the heaviest blows they can to bourgeois rule and in this way hastening its international overthrow.

Revolutionary Realism

Yet the question remained: How could the workers maintain themselves in power in a democratic republic over the long haul if they constituted a minority of the populace? Luxemburg’s answer was that they could not — and yet the effort would still be worth it:

The revolution’s bourgeois character finds expression in the inability of the proletariat to stay in power, in the inevitable removal of the proletariat from power by a counterrevolutionary operation of the bourgeoisie, the rural landowners, the petty bourgeoisie, and the greater part of the peasantry. It may be that in the end, after the proletariat is overthrown, the republic will disappear and be followed by the long rule of a highly restrained constitutional monarchy. It may very well be. But the relations of classes in Russia are now such that the path to even a moderate monarchical constitution leads through revolutionary action and the dictatorship of a republican proletariat.

Shortly before writing this, in an address to a Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, she made the following remarks:

I find that it is a poor leader and a pitiful army that only goes into battle when victory is already in the bag. To the contrary, not only do I not mean to promise the Russian proletariat a sequence of certain victories; I think, rather, that if the working class, being faithful to its historical duty, continues to grow and execute its tactics of struggle consistent with the unfolding contradictions and the ever-broader horizons of the revolution, then it could wind up in quite complicated and difficult circumstances ... But I think that the Russian proletariat must have the courage and resolve to face everything prepared for it by historical developments, that it should, if it has to, even at the cost of sacrifices, play the role of the vanguard in this revolution in relation to the global army of the proletariat, the vanguard that discloses new contradictions, new tasks, and new paths for class struggle, as the French proletariat did in the nineteenth century.

She did not shy away from acknowledging the implications of this argument:

Revolution in this conception would bring the proletariat losses as well as victories. Yet by no other road can the entire international proletariat march to its final victory. We must propose the socialist revolution not as a sudden leap, finished in twenty-four hours, but as a historical period, perhaps long, of turbulent class struggle, with breaks both brief and extended.

This was a remarkable expression of revolutionary realism. Luxemburg was fully aware that even a democratic republic under the control of the working class — which is how she as well as Marx understood “the dictatorship of the proletariat” — was bound to be forced from power in the absence of an international revolution, especially in a country where the working class constituted a minority. And yet, even though the revolution would therefore have “failed” from at least one point of view, it would have produced important social transformations, providing the intellectual sediment from which a future uprooting of capitalism could arise.

In short, Luxemburg did not think that it made sense to sacrifice democracy for the sake of staying in power, since the political form required to achieve the transition to socialism was “thoroughgoing democracy”. If a nondemocratic regime stayed in power, the transition to socialism would become impossible, since the working class would be left without the means and training to exercise power on its own behalf. Yet on the other hand, if a proletarian democracy existed even for a brief period of time, it could help inspire a later transition to socialism.

Self-Examination

This argument speaks to what would unfold a decade later, when tsarism was finally overthrown in the February 1917 Revolution, followed in short order by the Bolshevik seizure of power in October of the same year. Lenin and the Bolsheviks were fully aware at the time that the material conditions did not permit the immediate creation of a socialist society, even as they proclaimed the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat. This was why Lenin worked so hard to foster proletarian revolutions in Western Europe.

However, two fundamental issues separated Lenin’s approach from that of Luxemburg. Firstly, his regime did not take the form of a democratic republic, as seen in its suppression of political liberties — a development that Luxemburg sharply opposed in her 1918 critique of the Russian Revolution. Secondly, Lenin held that once the Bolsheviks seized power, they intended to keep it — permanently. This was very different from Luxemburg’s statement that “the inability of the proletariat to stay in power” would not be the worst outcome, so long as the vision of liberation projected to the world through its creation of a democratic society based on the rule of the working class inspired others to take up the fight against capitalism.

Luxemburg’s position is especially striking because she was fully aware that the bourgeoisie would always resort to violent suppression in the aftermath of a defeated revolution. Indeed, she lost her own life following the defeat of the January 1919 Spartacus League uprising in Berlin, which she initially opposed on the grounds that it lacked sufficient mass support. However, Luxemburg was equally aware that any effort to forge a transition to socialism through nondemocratic means was doomed to fail. In this sense, she anticipated the tragic outcome of many revolutions in the decades following her death.

Whatever one makes of Luxemburg’s reflection on these issues, one thing is clear: she developed a distinctive, though rarely discussed, conception of the transition to socialism (especially for developing societies, which is what the Russian Empire was at the time) that has received far too little attention. The publication of these writings in English will hopefully remedy that neglect.

Although many of Luxemburg’s ideas speak to issues that democratic socialists, anti-imperialists, and feminists are grappling with today, on at least one critical issue, her perspective has not stood the test of time. It is to be found in her oft-repeated insistence: “When the sale of workers’ labour to private exploiters is abolished, the source of all today’s social inequalities will disappear.”

Luxemburg’s contention that the abolition of private ownership of the means of production would provide the basis for ending “every inequality in human society” was not hers alone. Virtually every tendency and theorist of revolutionary social democracy in the Second International shared it, including Lenin, Karl Kautsky, Leon Trotsky, and many others. Yet it is hardly possible to maintain this view today.

Neither the social-democratic welfare states, which sought to limit private property rights, nor the regimes in the USSR, China, and elsewhere in the developing world, which abolished them through the nationalization of property, succeeded in developing a viable alternative to the capitalist mode of production. A much deeper social transformation that targets not alone private property and “free” markets but most of all the alienated form of human relations that define capitalist modernity is clearly needed.

That is a task for our generation, which can be much aided by returning with new eyes to the humanist implications of Marx’s critique of the logic of capital. This entails a critical re-evaluation of the meaning of socialism that may not have been on the agenda in Luxemburg’s time, but which the overall spirit of her work surely encourages. As she wrote in 1906:

Self-examination — that is, making oneself aware at every step of the direction, logic, and basis for the class movement itself — is that store from which the working mass draws its strength, again and again, to struggle anew, and by which it understands its own hesitation and defeats as so many proofs of its strength and inevitable future victory.

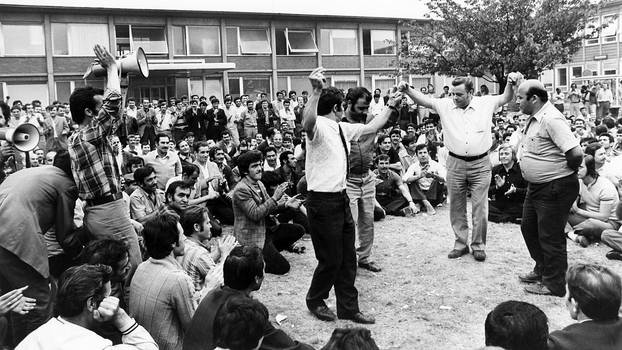

Striking Turkish workers at the Ford factory in Cologne-Niehl, 29 August 1973. The wildcat strike was triggered by the firing of 300 workers who returned home from vacation behind schedule, but in reality, it was about a lot more than that.

Striking Turkish workers at the Ford factory in Cologne-Niehl, 29 August 1973. The wildcat strike was triggered by the firing of 300 workers who returned home from vacation behind schedule, but in reality, it was about a lot more than that.

Members of the left-wing group Szikra demonstrate against the Orbán government’s plan to bring Chinese Fudan University to Budapest, 5 June 2021

Members of the left-wing group Szikra demonstrate against the Orbán government’s plan to bring Chinese Fudan University to Budapest, 5 June 2021