The Only Solution to “Wealth Supremacy” Is a Democratic Economy

Our economy must center human outcomes rather than rising share prices, says social theorist and author Marjorie Kelly.

The extraction of wealth is a pathology of late capitalism and is defined by the cultural and political processes by which the rich establish themselves as the dominant class. Social theorist and organizer Marjorie Kelly labels this phenomenon “wealth supremacy” which is also the title of her latest book. But as she points out in this exclusive interview for Truthout, wealth supremacy, which has institutionalized greed, defines a system that is not only biased but rigged against the great bulk of the population and thus detrimental to the economy, the citizens and the planet. She argues, in turn, that a movement to build a democratic economy is our only way out. Kelly is Distinguished Senior Fellow with the Democracy Collaborative. In addition to Wealth Supremacy: How the Extractive Economy and the Biased Rules of Capitalism Drive Today’s Crises (2023), she is the author of The Making of a Democratic Economy: Building Prosperity for the Many, Not Just the Few (coauthored with Ted Howard; 2019). The interview that follows has been lightly edited for clarity.

C. J. Polychroniou: One of the most pronounced developments over the past 40 years within the global economy, and particularly within developed countries, is financialization — which means finance has come to dominate our economy, our culture, the natural world, even our ostensibly democratic politics. Some say financialization represents a new phase of capitalism, while others see it as a consequence of neoliberalism. Your recent book, Wealth Supremacy, analyzes the current form of capitalism and shines a light on what you perceive as its core problem, while also offering a vision of an alternative system, a democratic economy — along with pathways to get there. Let’s start with what you mean by “wealth supremacy,” and how, in your own view, financialization came to dominate over all other forms of economic activity.

Marjorie Kelly: We can’t fix a problem that we can’t name. We point to “corporate power,” “inequality” and “greed” as the problem. But these don’t get to the root of the system’s dysfunction. I call it wealth supremacy — the bias that institutionalizes infinite extraction of wealth for the wealthy, even as it means stagnation or losses for the rest of us. Personal greed is certainly operating. But the system problem is how greed is mandated, rewarded, normalized and institutionalized in the practices and institutions of the system.

It’s mandated in how investments are managed, how corporations are governed; the aim of both is maximum income to capital. In operation, wealth supremacy takes the form of capital bias — the way only capital votes in corporations, how a rising stock market is equated with a successful economy.

Neoliberal government policies let this capital-centric machine loose. The result was financialization — the churning out of more and more financial wealth.

Don’t Dismiss Marx. His Critique of Colonialism Is More Relevant Than Ever.

Contrary to liberal misinterpretations, Marx was a fierce critic of colonialism, says Marxist scholar Marcello Musto.

By C.J. Polychroniou , TRUTHOUT December 14, 2023

Behind it all is the aim of keeping the wealthy on top, protected, comfortable. Wealth supremacy is a manifestation of class bias. It’s about the countless ways our culture favors the wealthy, the upper class. Class is many things — exquisite taste in art and wine, speaking and dressing well, having children attend the right schools — but it stands on a foundation of wealth, which makes possible all the rites of class.

Building wealth is certainly a goal that many people aspire to; yet, in your book, you argue that the ongoing processes of piling up wealth are actually detrimental to the economy, to citizens and to the planet. How is wealth detrimental? And who’s the culprit here — the culture of “wealth supremacy” or capitalism itself?

The real problem is excess wealth — like the eight billionaires who own half the world’s wealth. But the culture of our economy in general supports, in fact mandates, maximum wealth extraction. When investors look at their/our portfolio returns, we step into the dreamworld of wealth, the fiction that financial gains somehow fall from the sky, pristine and unblemished. The system is so focused on benefit to wealth that it ignores the impact on others. Wealth has an underside we rarely talk about.

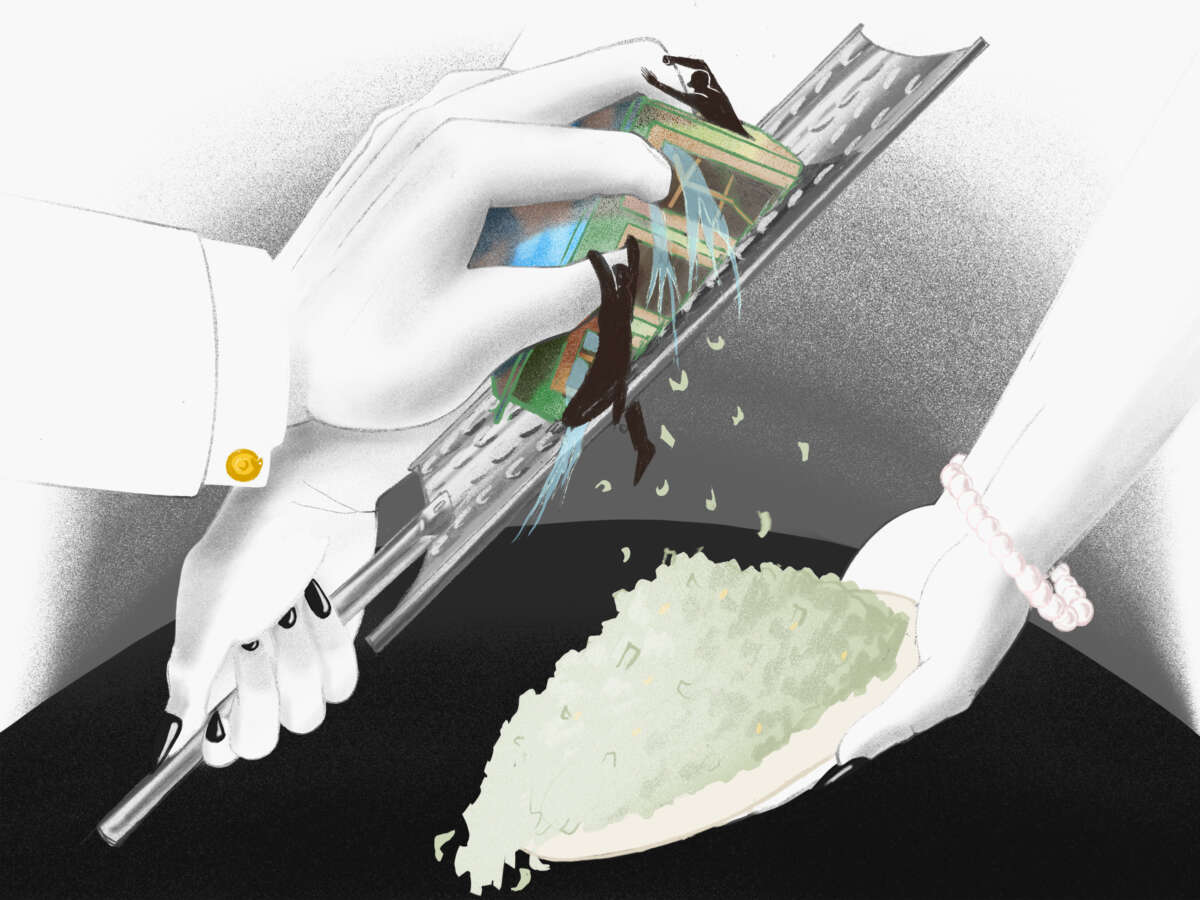

At the Democracy Collaborative where I work, we commissioned work by three international economists who demonstrated how wealth grows by extraction. Every asset held by one person represents a claim on someone or something else. Credit card debt is a claim against your checkbook. Shares of stock are a claim on the value of a corporation and growing that value for wealthy shareholders often means laying off workers, or turning full-time jobs into part-time and Uberized jobs, in order to shift income from labor to capital. The problem isn’t just that wealth is unequal. As these international economists demonstrated, the financial sector has become the locus where inequality is created.

As our society watches the wealth of multimillionaires and billionaires magically expand as though out of thin air, much of that wealth is being extracted from the pockets of ordinary people and our taxpayer-financed governments. We’re told we’re in a “trickle-down” economy. The truth is the reverse: What’s happening is a vacuuming upward. Financial assets have become a giant sucking action squeezing consumer pocketbooks, creating unemployment, pushing housing prices to unreachable heights, creating monopolies that hampers family businesses, blocking our ability to tackle climate change, destabilizing the economy with stock market booms and busts. And enabling billionaires to capture democracy.

Capitalism is this system of extraction. Its aim is keeping the wealthy rolling in clover. Our culture helps to hold it all in place — to legitimize it — when we revere the wealthy as the possessors of godlike powers, and when we accept the operations and institutions of the economy as normal, necessary and benign. Calling it out as a system of bias is a step toward delegitimizing it, turning its cultural foundation to sand.

You write about the myths of wealth supremacy that normalize the system’s bias. What are some of those myths and how do they impact politics and democratic governance in particular?

I identify seven myths that form the operating system of our economy. The core myth is the myth of maximizing — the idea that no amount of wealth is ever enough. That’s the basic principle of investing. In the book, I distinguish “profit making” from “profit maximizing.” Businesses need to make a profit to survive, but maximizing unleashes damage to society and destruction of the Earth.

There’s the myth of corporate governance, which says workers are not members of the corporation. Workers can go to a company every day for 40 years, keeping the place running, but they’re outsiders. Hedge fund investors holding shares for 15 minutes are the insiders, because only capital has a vote for the board. Workers are dispossessed and disenfranchised.

There’s the myth of materiality in corporate and financial accounting, which says that gains to capital alone are real. Impacts on the environment or society aren’t real, aren’t “material,” unless they affect capital. ExxonMobil increased shareholder value by in 2022. That’s considered a success. No matter that these products are fueling catastrophic wildfires and flooding cities.

We’re told we’re in a “trickle-down” economy. The truth is the reverse: What’s happening is a vacuuming upward.

Important for our politics is the myth of the free market, which says government is to be subdued, for it’s the enemy of the independence and power of wealth. There shall be no limits on the field of action of corporations and capital.

This myth is about letting the machine of wealth extraction run unimpeded. Yet as that machine revs into overdrive — financial assets are now five times GDP in the U.S., and even more in the U.K. — ongoing extraction becomes more difficult. Regulations need to be knocked down, monopolies built up, good jobs eliminated, taxes evaded. But regular folks in a democracy don’t support such an agenda. Thus, the party of wealth gets white working-class resentment on its side by blaming immigrants, inflaming racial bias. And it seeks to destroy democracy itself — vilifying the very concept of government, deploying dark money to change how ballots are cast and counted. Or pitching the Big Lie, as Donald Trump is doing. Yet beyond Trump, as Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse has said, the broader assault on democracy is run by a small billionaire elite.

What helped remake U.S. politics was financialization. This led to runaway inequality — creating the expanding pool of the disaffected working class — while also creating the wealth that shifted policy toward corporations and the rich. The post-1980 neoliberal era marked the rise of the plutocracy — what Whitehouse calls “the unseen ruling class.” Destroying democracy is part of its game plan to keep the wealth extraction machine going.

In what I understood to be an attempt on your part to interfuse class and race, you wrote that white supremacy and wealth supremacy are closely related. Are you saying that capitalism has color?

These two forms of bias are deeply intertwined. In the initial phase of what Guyanese intellectual Walter Rodney called the “capitalist/imperialist system,” much wealth came from extracting from persons and nations of color, through slavery and imperial possession. Racial extraction by finance continued in modern times through redlining, predatory mortgages, and more.

But if systems of wealth supremacy and white supremacy work together, they also function by separate logics. White supremacy persists, inflicting harm across generations. Yet wealth supremacy accelerates. Because the larger the sphere of swollen wealth becomes, the greater extraction it requires in order to grow larger still. If people of color have long been and remain primary targets for this extraction, today the planet itself is caught in its iron grip. And the suffering that people of color have long known is hitting white people.

State socialism is pretty much dead, and social democracy is on its knees. First, how do we go about changing the current system and, second, what would a democratic economy look like?

So now we’re talking about system change. Not regulating capitalism, but shifting to a next system, where capital is no longer at the center. It starts by recognizing that ownership and control of our political economy by a wealthy elite is the core problem. Then the solution becomes clear. We need to preserve political democracy and bring its spirit into the economy itself — creating a democratic economy, where wealth and power are held broadly, where economic institutions and practices are designed to allow all of us to prosper on a flourishing Earth.

How do we get there? We need a great ownership transition, including public ownership of key sectors like water and health care, worker ownership of enterprise, protection of the commons through trusts and preserves, just ownership and control of land, forests and housing. And we need corporations redesigned to have a legal obligation to serve the public good. The profit-maximizing corporation that exists to make the rich richer can no longer be allowed to exist.

We also need a next system of capital — including debt forgiveness when necessary, a new ecosystem of banking in the public interest, authentic impact and local investing, and wealth and inheritance taxes that prohibit the formation of dynasties. Also needed are regulations reining in the super-predators, the uber-extractors like private equity and hedge funds.

I’m often asked if all this is possible. And I like to break that question into two parts. Are these new models of a democratic economy — like public banks and worker-owned firms — are these models feasible? The answer is yes. They’re proven. They’re practical. They’re superior in their outcomes, if success means human well-being rather than just a rising share price.

The second question then is: Is system change possible? But if we had started there with climate change — asking if it’s possible to cut carbon emissions by 80 percent — we would have given up. As Nelson Mandela said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.”

System change doesn’t start by asking if transformation is possible. Instead, we ask: Is it necessary? It’s here we begin.

One thing we can know with some certainty. A world half plutocratic and half democratic cannot endure long. One half will eventually supersede the other. Either the plutocratic economy will destroy democracy, or we’ll suffuse democracy into our economy, building the democratic economy now necessary to our survival.