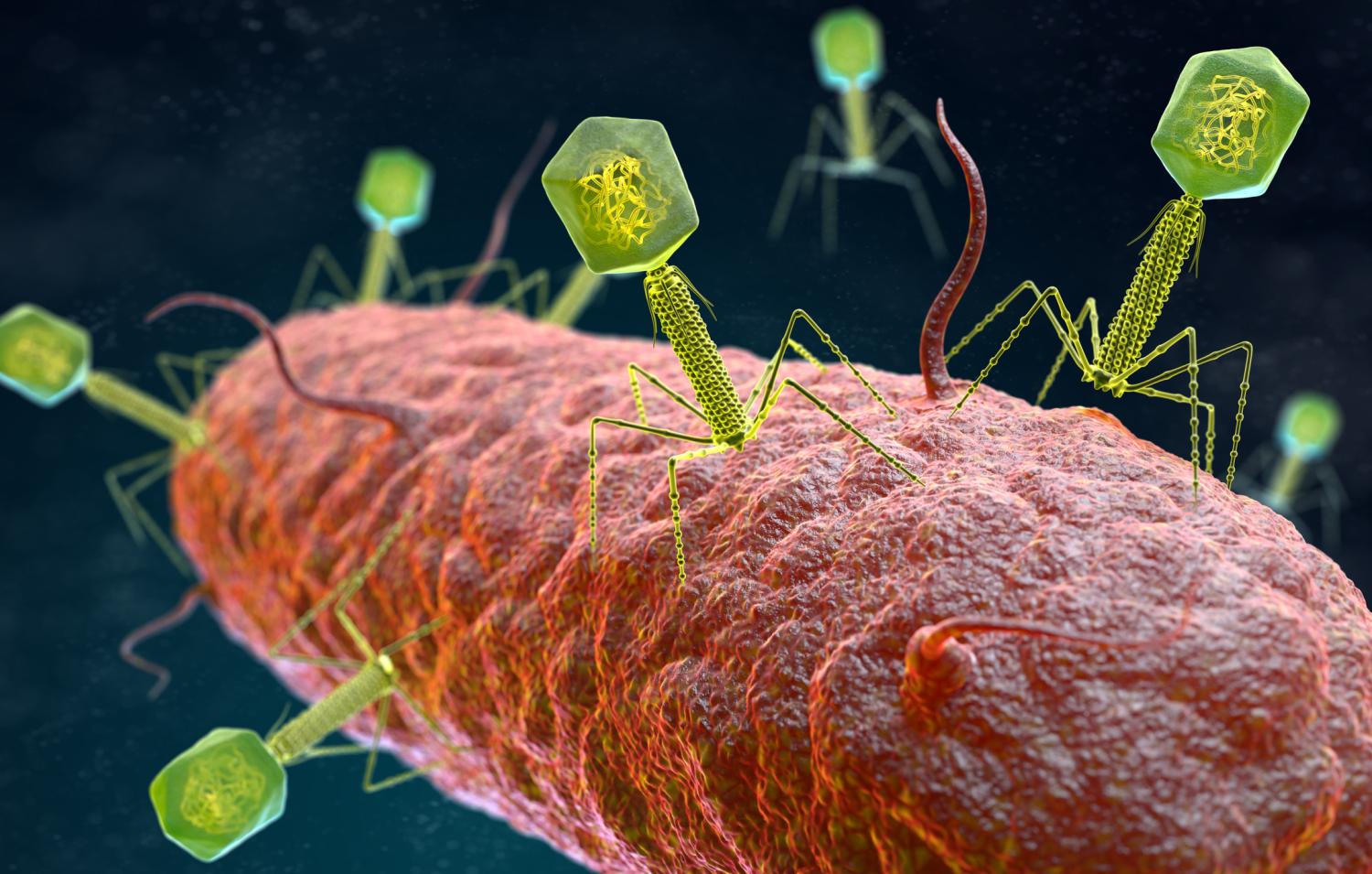

Meat and dairy production are linked to emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

By Cara Buckley

Cara Buckley eats lots of plants.

Feb. 28, 2024

Amsterdam won’t be giving up its Gouda. Los Angeles eateries will keep serving up combinations of bacon, chicken, egg and blue cheese that are essential to its signature Cobb salads. And Scots can breathe a sigh of relief knowing that Edinburgh has no plans to outlaw haggis.

Yet officials from each of these cities want people to consume less dairy and meat. They are signatories to the Plant Based Treaty, which was launched in 2021 with the aim of calling attention to the role played by greenhouse gases that are generated by food production.

The treaty is not binding and its effect varies wildly, ranging from just messaging to concrete plans to reduce dairy and meat served in institutions and schools and cut down on food waste.

But local leaders who championed the treaty said it helped solidify their efforts to encourage plant consumption for both climate and health reasons, while also sending a pressing message.

“In Edinburgh, we’ve got quite ambitious climate plans, whether it’s energy or retrofitting public transport, but we were missing a key part of this, which was food,” said Ben Parker, a member of the Scottish Green Party on the Edinburgh City Council, which endorsed the treaty in early 2023. “Plant based foods have a massive role to play in terms of bringing down carbon emissions.”

The treaty grew out of the Animal Save Movement. As climate change worsened, one of its founders, Anita Krajnc, grew dismayed at how little both the heat trapping emissions and ecological destruction related to meat were factoring into global climate talks.

She and other activists modeled the Plant Based Treaty after the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, which calls on governments to stop new oil, gas and coal projects. Along with encouraging people to eat more plants, the Plant Based Treaty presses for no new land be cleared for animal agriculture and that ecosystems and forests be restored.

The first municipality to sign on was Boynton Beach, Fla., in September 2021. “It’s about raising awareness around individual choices and the benefits of eating more plants,” said Rebecca Harvey, the city’s former sustainability coordinator.

Twenty-five other municipalities have since joined, including Los Angeles, Amsterdam and more than a dozen cities in India.

Amsterdam spokesman Rory van den Bergh said the city is trying to change eating habits and is aiming for 60 percent of the protein consumed by residents to come from plants by 2030.

Have Climate Questions? Get Answers Here.

What’s causing global warming? How can we fix it? This interactive F.A.Q. will tackle your climate questions big and small.

Other signatories include Nobel laureates, politicians, scientists, physicians, athletes and celebrities, among them Joaquin Phoenix, Mara Rooney, Alicia Silverstone, Moby, and Paul McCartney and his daughters Mary and Stella, who launched the Meat Free Monday campaign in 2009.

Globally, food systems make up a third of planet-heating greenhouse gasses, with the environmental toll of the meat and dairy industries being particularly high. Livestock accounts for about a third of methane emissions, which have 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in the short term.

It’s also a water intensive industry. It takes 2,110 gallons of water to produce one pound of beef, 520 gallons of water to produce one pound of cheese and 410 gallons of water to produce one pound of chicken. By comparison, protein-rich lentils require 190 gallons of water per pound.

A 2023 study from the University of Oxford found that, compared to diets heavy in meat, vegan diets resulted in 75 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions, 54 percent less water use and 66 less biodiversity loss. The study’s author also calculated that if omnivores in the United Kingdom cut their meat intake in half, it would be equivalent to taking 8 million cars off the road.

Lambeth, one of London’s 32 boroughs, also signed onto the treaty. Jim Dickson, a councilor, said it dovetailed with efforts to encourage people to eat more fruits and vegetables to help improve health, along with “social prescribing” programs that got isolated individuals involved in community gardening. The borough also aims to reduce per-plate emissions of school meals in large part by shifting to more plant-based food.

There have been grumblings. “Some people have said that this is clearly a sinister plot to impose a meat tax or meat bans on local people, or that the nanny state is controlling people’s diets,” Mr. Dickson said, adding that none of it was true. And a rural organization has been pressing the Edinburgh City Council to cancel its backing of the treaty, saying it was “anti-farming.”

Edinburgh’s city council pressed on, adopting a Plant Based Treaty action plan in January that clarified that the city did “not seek to eliminate meat and dairy” but focus on high quality, sustainable, locally sourced food. “The action plan is about trying to make plant based foods as accessible as possible, and understanding that that’s going to be a journey,” said Mr. Parker, the city councilor.

Cara Buckely is a reporter on the climate team at The Times who focuses on people working toward climate solutions. More about Cara Buckley