Sep. 29, 2024

Tom Frantz, a manager with the state Department of Natural Resources, controls a Green Climber slope mower June 26 near Nile, Yakima County. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

By Amanda Zhou

Seattle Times staff reporter

Climate Lab is a Seattle Times initiative that explores the effects of climate change in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. The project is funded in part by The Bullitt Foundation, Jim and Birte Falconer, Mike and Becky Hughes, University of Washington and Walker Family Foundation, and its fiscal sponsor is the Seattle Foundation.

OKANOGAN-WENATCHEE NATIONAL FOREST — The teeth of the mower chewed through a stand of small trees and shrubs 30 miles from Mount Rainier and belched out a brown cloud of dirt and wood chips.

Tom Frantz, a manager with the state Department of Natural Resources, used a joystick to control this tool remotely. DNR hopes it can help thin Washington’s overcrowded forests that are primed for wildfire.

The work is part of DNR’s 20-year plan to improve forest health in Central and Eastern Washington and includes not only mechanical treatments like the mower but also prescribed burns. It also marks a different approach to managing forestland and wildland firefighting in the West.

This is a mammoth undertaking with hundreds of thousands of acres needing help. The Legislature in 2021 budgeted $500 million over eight years to get things started and help communities prepare for wildfire. So far, groups including DNR, the U.S. Forest Service, tribes, commercial and private landowners, and other state agencies have completed nearly 800,000 acres of treatment, of its goal of 1.25 million acres by 2037.

The stakes are high in a state that has seen record wildfires in recent years. Washington had its second- and third-worst fire seasons in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Wildfires in the Pacific Northwest have also destroyed hundreds of homes and structures, devalued timber sales, closed highways and foiled carbon sequestration plans.

After over a century of policies that prioritized fire suppression, unhealthy and overgrown forests are widespread across Eastern Washington. When a wildfire sweeps through these forests, which historically would experience periodic fires, they burn to a crisp because of decades of accumulated leaves, pine needles, shrubs and younger trees in the understory.

Nevertheless, barriers and questions remain. Prescribed fire, an essential step in making forests more resilient to wildfire, has been thwarted by workforce shortages and regulatory roadblocks. Hundreds of thousands to millions of acres still need some kind of intervention to be restored to health. Conservationists have also questioned to what degree the plan has changed operations at the massive agency and how much of DNR’s own resilience work is its standard forest harvests repackaged under a new name.

Wildfire season in the Pacific Northwest is expected to become longer and more intense as summers are anticipated to become hotter and drier. Forest resiliency scientists argue the treatments — if done at scale — have the potential to fundamentally change fire behavior in the state.

What does a healthy forest look like?

An hour drive outside Mount Rainier National Park, the forest road tunnels through a blanket of dense, decades-old pine and fir trees. You can barely see through the understory, and tree trunks brush up against the needles of younger Douglas firs, only a few feet tall.

This view might seem natural to the hikers, campers and motorcyclists who visit the area each summer, but to those who have studied these landscapes, their composition is the result of decades of Western forest management.

Forest fires emerged as a natural enemy in the early days of settlement, when timber made up as much as 90% of the country’s energy needs for things like heating, cooking, construction and toolmaking, said Lincoln Bramwell, the U.S. Forest Service’s chief historian. Prevailing scientific understanding on forests came from countries like France or Germany, which don’t experience the same type of forest fires. Settlers considered wildfire something that needed to be eliminated.

Yet Indigenous people understood the necessity of wildfire for a healthy forest ecology, often lighting fires of their own to cleanse the land.

When settlers moved west, they fought wildfires directly, killed Indigenous people en masse and outlawed cultural burning practices, said Sean Parks, research ecologist with the Forest Service. The number of annual wildfires had dropped sharply by 1880 and the formation of the Forest Service in 1905 created a formal agency tasked with ridding forests of wildfire, he said.

By the 1950s, wildfires that used to burn around 30 million acres each year now burned close to 3 million a year, said Timothy Ingalsbee, a wildfire ecologist and the executive director of the nonprofit Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology. During these decades, forests across the American West were accumulating a fire deficit. Grasses, shrubs and trees that historically burned away collected and piled up.

In Eastern Washington, around half of the forests have historically experienced low-intensity wildfires every five to 25 years, which would open up spaces for animals like deer to travel through and recycle nutrients in the soil. These forests would be dominated by fire-resistant species like Douglas fir and ponderosa pine, which rely on fires to open their cones and distribute their seeds.

“For the most part in Eastern Washington, fire was just part of the system that maintained and shaped it,” said Derek Churchill, a DNR forest health scientist.

Many forests across Eastern Washington now lack forests with large and medium trees where less than 40% of the sky is covered by tree canopies.

“We’ve done such an amazing job, even on the federal lands, of removing those large, old trees that we’re in a deep deficit. We don’t have anywhere near the number that we would have historically,” said Dave Werntz, a science and conservation director at Conservation Northwest.

An hour drive outside Mount Rainier National Park, the forest road tunnels through a blanket of dense, decades-old pine and fir trees. You can barely see through the understory, and tree trunks brush up against the needles of younger Douglas firs, only a few feet tall.

This view might seem natural to the hikers, campers and motorcyclists who visit the area each summer, but to those who have studied these landscapes, their composition is the result of decades of Western forest management.

Forest fires emerged as a natural enemy in the early days of settlement, when timber made up as much as 90% of the country’s energy needs for things like heating, cooking, construction and toolmaking, said Lincoln Bramwell, the U.S. Forest Service’s chief historian. Prevailing scientific understanding on forests came from countries like France or Germany, which don’t experience the same type of forest fires. Settlers considered wildfire something that needed to be eliminated.

Yet Indigenous people understood the necessity of wildfire for a healthy forest ecology, often lighting fires of their own to cleanse the land.

When settlers moved west, they fought wildfires directly, killed Indigenous people en masse and outlawed cultural burning practices, said Sean Parks, research ecologist with the Forest Service. The number of annual wildfires had dropped sharply by 1880 and the formation of the Forest Service in 1905 created a formal agency tasked with ridding forests of wildfire, he said.

By the 1950s, wildfires that used to burn around 30 million acres each year now burned close to 3 million a year, said Timothy Ingalsbee, a wildfire ecologist and the executive director of the nonprofit Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology. During these decades, forests across the American West were accumulating a fire deficit. Grasses, shrubs and trees that historically burned away collected and piled up.

In Eastern Washington, around half of the forests have historically experienced low-intensity wildfires every five to 25 years, which would open up spaces for animals like deer to travel through and recycle nutrients in the soil. These forests would be dominated by fire-resistant species like Douglas fir and ponderosa pine, which rely on fires to open their cones and distribute their seeds.

“For the most part in Eastern Washington, fire was just part of the system that maintained and shaped it,” said Derek Churchill, a DNR forest health scientist.

Many forests across Eastern Washington now lack forests with large and medium trees where less than 40% of the sky is covered by tree canopies.

“We’ve done such an amazing job, even on the federal lands, of removing those large, old trees that we’re in a deep deficit. We don’t have anywhere near the number that we would have historically,” said Dave Werntz, a science and conservation director at Conservation Northwest.

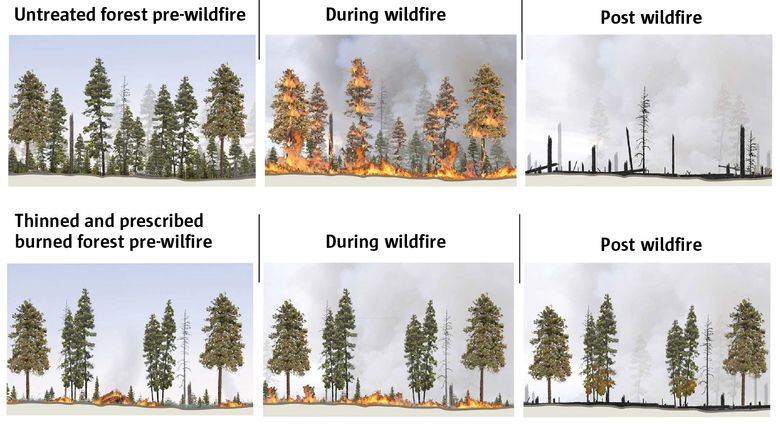

How forests can better survive wildfire

In Eastern Washington, fire has long been a natural part of the landscape. However, policies that have prioritized fire suppression have led to overgrown forests that are not able to survive wildfire when it does come through. Forest health experts say a combination of reducing the tree density with thinning and prescribed fire can help boost survival rates for the largest and oldest trees, which may already be fire-tolerant species.

Source: “Tamm review: A meta-analysis of thinning, prescribed fire, and wildfire effects on subsequent wildfire severity in conifer dominated forests of the Western US,” Forest Ecology and Management, Volume 561, June 1, 2024, 121885; sciencedirect.com (Illustrations by Eric Sloniker, graphic by Mark Nowlin / The Seattle Times)

According to scientific research on Pacific Northwest forests, around 3 million acres of the 10 million acres of forested lands in Eastern Washington are unhealthy and need prescribed fire, thinning, time or a combination to restore the landscape to a resilient condition. However, not all of that land is accessible to humans.

So far in higher-priority lands, DNR has estimated that at least 900,000 to 1.3 million acres in Eastern Washington need thinning or fire. The need will always surpass what resources are available, especially after taking into account that treated lands require maintenance, Churchill said.

During the 2021 Schneider Spring’s fire, the area on the right, which had previous had been thinned and prescriptively burned, survived better than the area on the left, which was... (Courtesy Washington Department of Natural Resources)More

Since 2017, various agencies in Washington have completed 790,790 acres of treatment like thinning and pruning, though after accounting for the fact that those treatments often happen on the same pieces of land, the actual footprint of the treatments total around 381,000 acres.

As proof of the efficacy of forest treatments, the DNR likes to point out one area in the massive 2021 Schneider Springs fire near Mount Rainier National Park. On one side of a road, the U.S. Forest Service cut down trees in 2008, created slash piles a year later and did a prescribed burn in 2013. The forest on the other side of the road was untreated

After the fire, the difference between the two sides of the road was stark.

On the untreated side, the trees look like spiky black toothpicks. On the treated side, the trees survived and still have green canopies, despite some scorching near their base. With less dead vegetation on the ground, fewer understory trees and more room between trees, the fire burned less intensely and wasn’t able to travel up the existing trees. Naturally fire-resistant ponderosa pines have thick bark and don’t have branches low to the ground that can help a fire climb to the canopy.

Barriers around fire and questions from conservationists

The lack of prescribed fire threatens to be the biggest bottleneck of all in Washington’s forest resiliency plans.

Only around 23% of all treatments and 12% of DNR’s treatments since 2017 were prescribed fires, according to data collected by DNR. Most of those treatments were when piles of branches, shrubs and “slash” were burned and only around 0.5% of all the treatments were “broadcast burns,” or when an entire section of a forest floor was cleared of vegetation. DNR ignited its first prescribed burn of that kind in two decades in 2022. Other agencies, like the Forest Service and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, have been conducting prescribed burns for longer.

Earlier this year, Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz wrote that the amount of prescribed fire called for by the state’s scientific work is at least five times what is currently done.

The lack of prescribed burning can be blamed on workforce shortages and regulatory hurdles, said DNR assistant division manager Kate Williams. She said the state has a narrow burn window in the spring and fall, and if firefighters are already out on wildfires, there may not be personnel available to perform prescribed burns.

Washington’s air-quality standards are also more strict than federal requirements and do not have the flexibility needed, she said.

Experts have also argued that because the scale of the issue is so large, there needs to be more “managed fire,” or wildfires that are allowed to burn in a larger area without harming nearby communities.

While this can happen on federal land, Williams said, state laws still require immediate suppression of wildfire and DNR still aims to keep fires small to protect timber.

It’s unclear so far whether the current rate of treatment is fast enough to make a difference in some communities, said Katie Fields, Conservation Action’s Forest and Communities program manager, but generally thinning and prescribed fire “needs to happen on a much more rapid scale.”

“If they meet the goal [of 1.25 million acres of treatment] and they’re not really getting prescribed fire back in the landscape, it feels questionable whether those stands will be at the level of forest health that we’re seeking,” Fields said.

Conservationists have also expressed concern over certain DNR timber harvests that are counted as forest health work. DNR reports the highest amount of these harvests counting as treatments.

While there are cases when a clear-cut can help restore a landscape, Werntz, with Conservation Northwest, said he is skeptical that the amount DNR is doing is actually what the science calls for. Rachel Baker, the forest program director with Washington Conservation Action, agreed and said she would like more details about these treatments from DNR.

Churchill acknowledged that these treatments are done to make money for DNR and its beneficiaries but said they “often” include forest-health benefits, like shifting the area to more resilient fire-resistant species or creating open habitat. DNR spokesperson Will Rubin added that these tree harvests are different from standard timber harvests in Western Washington, and in all of DNR’s cuttings, a certain number of trees are left standing.

“We know people have economic objectives. Can people meet those objectives and still meet these other broader forest-health goals? I think we can. The devil is in the details in particular landscapes,” Churchill said.

Regardless, DNR has been hoping to expand more of its treatments to Western Washington. While fire has been historically less frequent here, research suggests these areas could see at least twice as much fire activity in the 30 years after 2035.

But the job will never be over when you consider that trees and other plants just keep on growing, said Chuck Hersey, DNR forest health environmental planner.

“You gotta run faster than the treadmill and keep running faster than the treadmill or else you’re gonna fall off. That’s our challenge,” he said.

Seattle Times climate reporter Conrad Swanson contributed reporting.

Amanda Zhou: 206-464-2508 or azhou@seattletimes.com; Amanda Zhou covers climate change and the environment for The Seattle Times.

The lack of prescribed fire threatens to be the biggest bottleneck of all in Washington’s forest resiliency plans.

Only around 23% of all treatments and 12% of DNR’s treatments since 2017 were prescribed fires, according to data collected by DNR. Most of those treatments were when piles of branches, shrubs and “slash” were burned and only around 0.5% of all the treatments were “broadcast burns,” or when an entire section of a forest floor was cleared of vegetation. DNR ignited its first prescribed burn of that kind in two decades in 2022. Other agencies, like the Forest Service and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, have been conducting prescribed burns for longer.

Earlier this year, Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz wrote that the amount of prescribed fire called for by the state’s scientific work is at least five times what is currently done.

The lack of prescribed burning can be blamed on workforce shortages and regulatory hurdles, said DNR assistant division manager Kate Williams. She said the state has a narrow burn window in the spring and fall, and if firefighters are already out on wildfires, there may not be personnel available to perform prescribed burns.

Washington’s air-quality standards are also more strict than federal requirements and do not have the flexibility needed, she said.

Experts have also argued that because the scale of the issue is so large, there needs to be more “managed fire,” or wildfires that are allowed to burn in a larger area without harming nearby communities.

While this can happen on federal land, Williams said, state laws still require immediate suppression of wildfire and DNR still aims to keep fires small to protect timber.

It’s unclear so far whether the current rate of treatment is fast enough to make a difference in some communities, said Katie Fields, Conservation Action’s Forest and Communities program manager, but generally thinning and prescribed fire “needs to happen on a much more rapid scale.”

“If they meet the goal [of 1.25 million acres of treatment] and they’re not really getting prescribed fire back in the landscape, it feels questionable whether those stands will be at the level of forest health that we’re seeking,” Fields said.

Conservationists have also expressed concern over certain DNR timber harvests that are counted as forest health work. DNR reports the highest amount of these harvests counting as treatments.

While there are cases when a clear-cut can help restore a landscape, Werntz, with Conservation Northwest, said he is skeptical that the amount DNR is doing is actually what the science calls for. Rachel Baker, the forest program director with Washington Conservation Action, agreed and said she would like more details about these treatments from DNR.

Churchill acknowledged that these treatments are done to make money for DNR and its beneficiaries but said they “often” include forest-health benefits, like shifting the area to more resilient fire-resistant species or creating open habitat. DNR spokesperson Will Rubin added that these tree harvests are different from standard timber harvests in Western Washington, and in all of DNR’s cuttings, a certain number of trees are left standing.

“We know people have economic objectives. Can people meet those objectives and still meet these other broader forest-health goals? I think we can. The devil is in the details in particular landscapes,” Churchill said.

Regardless, DNR has been hoping to expand more of its treatments to Western Washington. While fire has been historically less frequent here, research suggests these areas could see at least twice as much fire activity in the 30 years after 2035.

But the job will never be over when you consider that trees and other plants just keep on growing, said Chuck Hersey, DNR forest health environmental planner.

“You gotta run faster than the treadmill and keep running faster than the treadmill or else you’re gonna fall off. That’s our challenge,” he said.

Seattle Times climate reporter Conrad Swanson contributed reporting.

Amanda Zhou: 206-464-2508 or azhou@seattletimes.com; Amanda Zhou covers climate change and the environment for The Seattle Times.

:

:

Britain announced plans to close all its coal-fired power stations by 2025, such as Ferrybridge in northern England. © OLI SCARFF / AFP

Britain announced plans to close all its coal-fired power stations by 2025, such as Ferrybridge in northern England. © OLI SCARFF / AFP