Residents of the Mariana Islands are pushing to revive their indigenous language amid fears it might soon die out

Anita Hofschneider in Guam Wed 12 Feb 2020

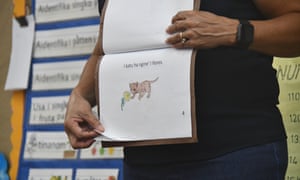

Bertilia Yamasta teaches her kindergarten class at at P.C. Lujan Elementary in Guam to speak CHamoru, the traditional language of the Mariana Islands. Photograph: Anita Hofschneider/The Guardian

Bertilia Yamasta moves a pointer across letters of the alphabet decorating the wall of her classroom. She’s standing before more than a dozen kindergarten students dressed in green-collared shirts who squirm on the carpet as she leads them in familiar recitations.

“A, å, b, ch, d,” the group says, calling out the alphabet backwards and forwards.

The students are speaking in CHamoru, the indigenous language of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific. And they’re among a shrinking number of people in the Marianas who actually know their ancestral tongue.

Guam: life in the nuclear firing line – in pictures

Yamasta’s class, at PC Lujan elementary, is the first publicly funded CHamoru immersion school on Guam, the southernmost and most populous island in the archipelago. The program is part of a broader effort to preserve and revitalise the CHamoru, also spelled Chamorro, language, which like many other indigenous languages worldwide is at risk of disappearing.

Bertilia Yamasta moves a pointer across letters of the alphabet decorating the wall of her classroom. She’s standing before more than a dozen kindergarten students dressed in green-collared shirts who squirm on the carpet as she leads them in familiar recitations.

“A, å, b, ch, d,” the group says, calling out the alphabet backwards and forwards.

The students are speaking in CHamoru, the indigenous language of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific. And they’re among a shrinking number of people in the Marianas who actually know their ancestral tongue.

Guam: life in the nuclear firing line – in pictures

Yamasta’s class, at PC Lujan elementary, is the first publicly funded CHamoru immersion school on Guam, the southernmost and most populous island in the archipelago. The program is part of a broader effort to preserve and revitalise the CHamoru, also spelled Chamorro, language, which like many other indigenous languages worldwide is at risk of disappearing.

Yamasta’s class is the first publicly-funded CHamoru immersion school on Guam, where US military forces once banned the language and burned CHamoru dictionaries. Photograph: Anita Hofschneider/The Guardian

Rufina Mendiola, who leads the Guam department of education’s CHamoru studies program, says the class is still a pilot program but the plan is to expand it through fifth grade.

“We cannot just stop now. We need to look ahead,” she says.

Mendiola’s sense of urgency reflects the diminishing number of CHamoru speakers. Although there’s little data about how many people still speak CHamoru, it’s clear the language is vulnerable.

The Mariana Islands are divided into two administrative areas – Guam in the south, which is a US territory with a population of 165,000, and the Northern Marianas, which has a population of about 60,000 people and, like Puerto Rico, is a commonwealth of the US.

A decade ago, the US census estimated there were about 25,827 CHamoru speakers on Guam, just 2,394 of whom were under the age of 18, and only 14,176 CHamoru speakers in the rest of the island chain.

Robert Underwood, the former president of the University of Guam, says most of the fluent speakers are likely to be over the age of 50.

“In another 20 to 30 years there may not be any real first-language speakers of CHamoru,” he says.

Underwood is leading a new effort to document the language backed by a $275,000 (£210,000) grant from the National Science Foundation.

But even if the language survives, centuries of colonisation have already irrevocably changed it. The Mariana Islands spent more than 300 years under Spanish colonial rule. Today it’s far more common to hear CHamoru speakers use Spanish numbers to count rather than the traditional numeric systems. And many words have been lost, such as the names of some colours.

Sacrificed on the altar of Americanisation

American military rule on Guam in the first half of the 20th century further contributed to the language loss. The US navy banned CHamoru in 1917 “except for official interpreting”. The naval administration even burned CHamoru-English dictionaries.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the ban on speaking CHamoru in schools was lifted, says Michael Bevacqua, a CHamoru language educator on Guam. Until then, schoolchildren who spoke CHamoru were punished, and their parents were sometimes even fined.

Bevacqua says that after the second world war, many parents on Guam were afraid that teaching their children CHamoru would limit their chances of success in the US.

“One of the things that they sacrificed on the altar of Americanisation was their language,” he says. That’s why today children like those in Yamasta’s class are a “novelty”.

Ann Marie Arceo is determined to change that. In 2005, Arceo founded Chief Hurao Academy, a nonprofit organisation that offers a CHamoru summer immersion program, an after-school immersion program and a CHamoru-language preschool.

Arceo says on the first day of registration, she expected 10 children to show up. Instead, there were more than 200. The overwhelming interest reflects a broader cultural renaissance in Guam, where there’s been a resurgence in pride in CHamoru history and identity.

“This millennial generation is wanting to know who they are and thirsting to fill an identity somehow,” Arceo says.

But creating fluent CHamoru speakers isn’t easy.

CHamoru language schools need funding, and that’s not always available. Federal funding recently expired for a similar language immersion program in the Northern Mariana Islands.

Experts warn that without intervention, there may not be any first-language speakers of the CHamoru language within 30 years. Photograph: Anita Hofschneider/The Guardian

Guam’s new immersion program has two years of funding, but getting the program off the ground is still challenging. At the start of the school year, Yamasta says her students were mostly quiet and unsure. A few knew a little CHamoru and one got frustrated to the point of tears. Yamasta felt overwhelmed translating lesson plans and looking for materials to help her teach effectively.

But several months in, the children are constantly chatting in CHamoru. Every week Yamasta uses to make a new CHamoru-language book out of rough paper to help the children read. She bought child-sized kitchen and cashier sets to help them practice useful vocabulary. Their parents attend weekly CHamoru classes themselves to help keep up the language use at home.

On a recent afternoon, Yamaste watches as her class scrambles to finish addition and subtraction problems.

One by one, the children run up to her with their completed math worksheets and declare, “Esta manayan!” to indicate they’re finished.

“Maolik,” she tells them, which means good. “It makes me so proud,” she says.

Rufina Mendiola, who leads the Guam department of education’s CHamoru studies program, says the class is still a pilot program but the plan is to expand it through fifth grade.

“We cannot just stop now. We need to look ahead,” she says.

Mendiola’s sense of urgency reflects the diminishing number of CHamoru speakers. Although there’s little data about how many people still speak CHamoru, it’s clear the language is vulnerable.

The Mariana Islands are divided into two administrative areas – Guam in the south, which is a US territory with a population of 165,000, and the Northern Marianas, which has a population of about 60,000 people and, like Puerto Rico, is a commonwealth of the US.

A decade ago, the US census estimated there were about 25,827 CHamoru speakers on Guam, just 2,394 of whom were under the age of 18, and only 14,176 CHamoru speakers in the rest of the island chain.

Robert Underwood, the former president of the University of Guam, says most of the fluent speakers are likely to be over the age of 50.

“In another 20 to 30 years there may not be any real first-language speakers of CHamoru,” he says.

Underwood is leading a new effort to document the language backed by a $275,000 (£210,000) grant from the National Science Foundation.

But even if the language survives, centuries of colonisation have already irrevocably changed it. The Mariana Islands spent more than 300 years under Spanish colonial rule. Today it’s far more common to hear CHamoru speakers use Spanish numbers to count rather than the traditional numeric systems. And many words have been lost, such as the names of some colours.

Sacrificed on the altar of Americanisation

American military rule on Guam in the first half of the 20th century further contributed to the language loss. The US navy banned CHamoru in 1917 “except for official interpreting”. The naval administration even burned CHamoru-English dictionaries.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the ban on speaking CHamoru in schools was lifted, says Michael Bevacqua, a CHamoru language educator on Guam. Until then, schoolchildren who spoke CHamoru were punished, and their parents were sometimes even fined.

Bevacqua says that after the second world war, many parents on Guam were afraid that teaching their children CHamoru would limit their chances of success in the US.

“One of the things that they sacrificed on the altar of Americanisation was their language,” he says. That’s why today children like those in Yamasta’s class are a “novelty”.

Ann Marie Arceo is determined to change that. In 2005, Arceo founded Chief Hurao Academy, a nonprofit organisation that offers a CHamoru summer immersion program, an after-school immersion program and a CHamoru-language preschool.

Arceo says on the first day of registration, she expected 10 children to show up. Instead, there were more than 200. The overwhelming interest reflects a broader cultural renaissance in Guam, where there’s been a resurgence in pride in CHamoru history and identity.

“This millennial generation is wanting to know who they are and thirsting to fill an identity somehow,” Arceo says.

But creating fluent CHamoru speakers isn’t easy.

CHamoru language schools need funding, and that’s not always available. Federal funding recently expired for a similar language immersion program in the Northern Mariana Islands.

Experts warn that without intervention, there may not be any first-language speakers of the CHamoru language within 30 years. Photograph: Anita Hofschneider/The Guardian

Guam’s new immersion program has two years of funding, but getting the program off the ground is still challenging. At the start of the school year, Yamasta says her students were mostly quiet and unsure. A few knew a little CHamoru and one got frustrated to the point of tears. Yamasta felt overwhelmed translating lesson plans and looking for materials to help her teach effectively.

But several months in, the children are constantly chatting in CHamoru. Every week Yamasta uses to make a new CHamoru-language book out of rough paper to help the children read. She bought child-sized kitchen and cashier sets to help them practice useful vocabulary. Their parents attend weekly CHamoru classes themselves to help keep up the language use at home.

On a recent afternoon, Yamaste watches as her class scrambles to finish addition and subtraction problems.

One by one, the children run up to her with their completed math worksheets and declare, “Esta manayan!” to indicate they’re finished.

“Maolik,” she tells them, which means good. “It makes me so proud,” she says.

No comments:

Post a Comment