By Khalil Ashawi, Reuters•February 24, 2020

1-3 / 10

As Syrian forces advance on Idlib, families fear being trapped at Turkish border

Internally displaced boys walk near the wall in Atmah IDP camp, located near the border with Turkey

By Khalil Ashawi

ATMEH, Syria (Reuters) - Syrian government forces are advancing closer to the displaced persons camp where Adnan Abdelkarim and his family have taken shelter along the Turkish border after being uprooted multiple times, and he fears there is nowhere left to go.

"Today the regime is advancing from everywhere and we are trapped along the border," said 30-year-old Abdelkarim.

At the Atmeh camp on the northern edge of Idlib province, uprooted families are arriving in droves as they flee bombardment from air strikes and artillery shelling.

They fear being trapped between the fighting and the closed-off Turkish border. About 50 meters from the camp an imposing gray concrete wall is crowned with barbed wire, blocking their entry to Turkey.

"In the event the regime advances..., either we will die storming the Turkish wall and fleeing with our families...or slaughter ourselves by turning ourselves over," said Abdelkarim.

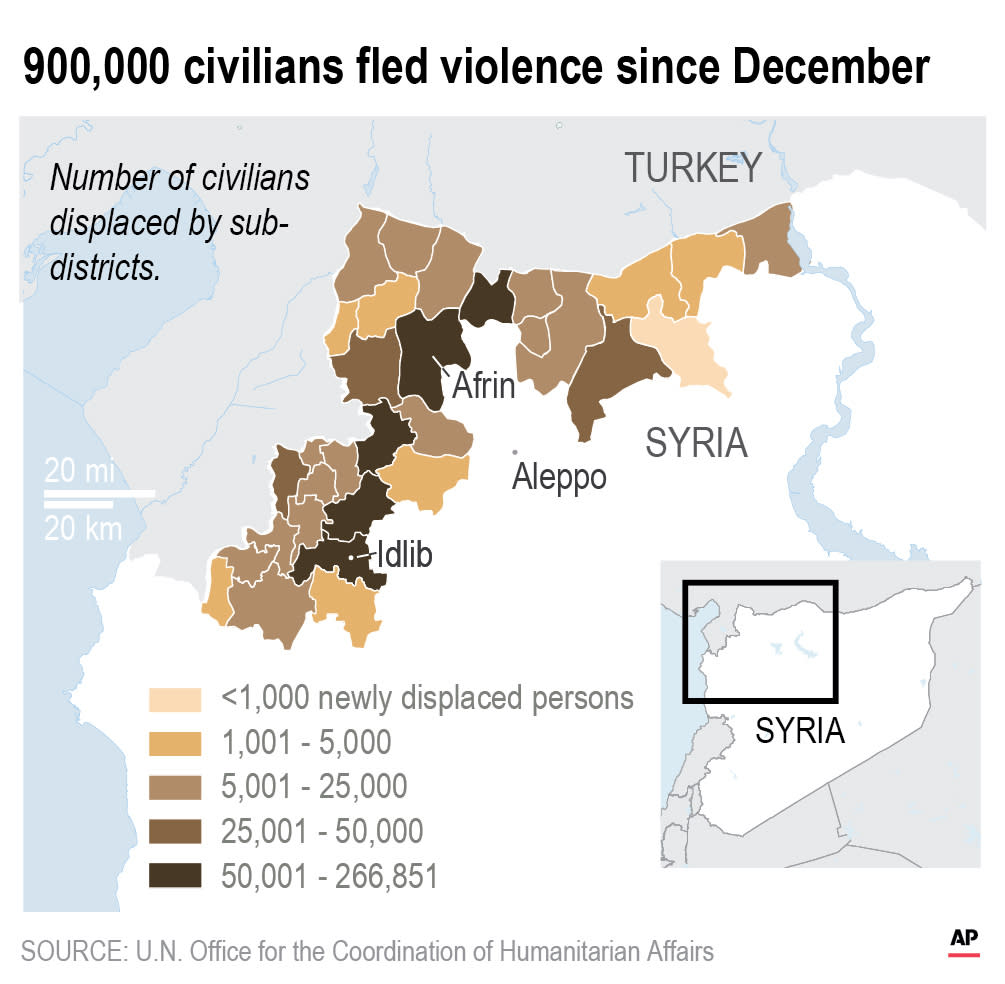

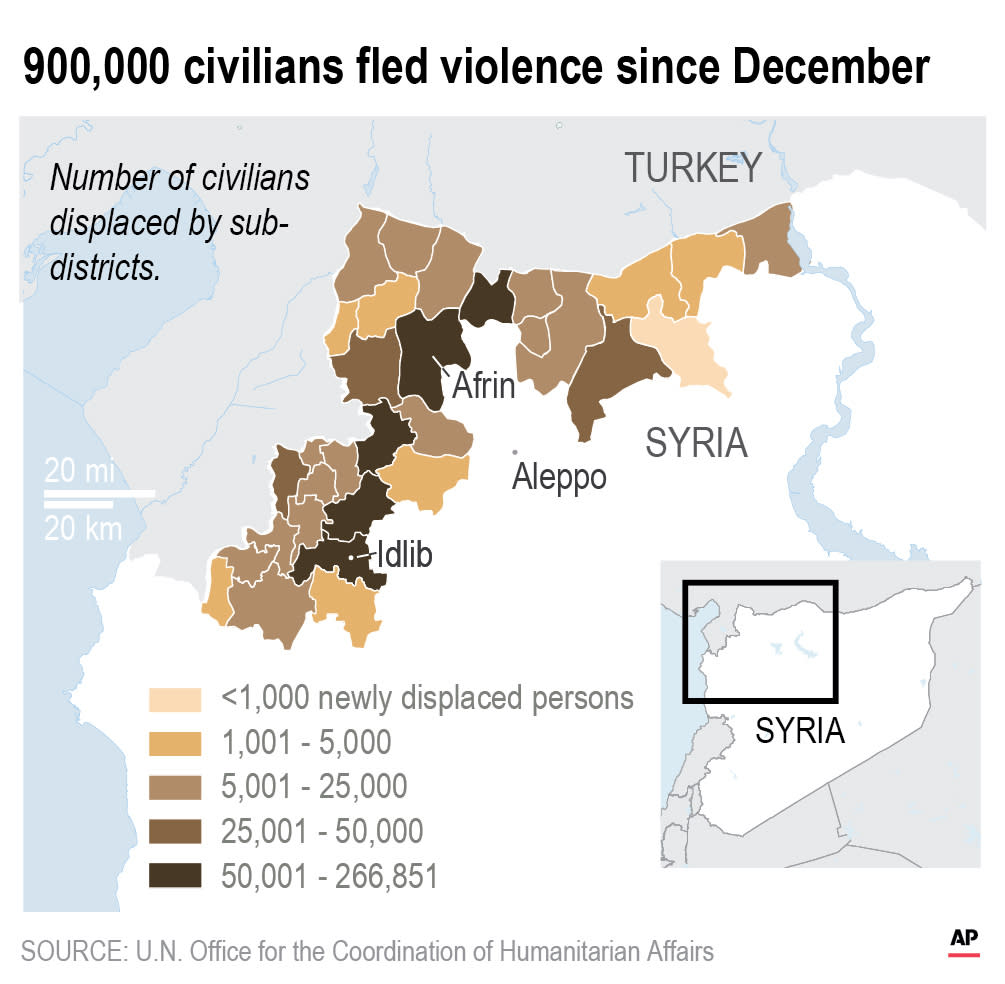

Backed by heavy Russian air power, Syrian government forces have stepped up a campaign to retake the last rebel stronghold in the northwestern regions of Aleppo and Idlib, sparking an exodus of nearly a million people toward a shrinking pocket along the Turkish frontier.

On Monday, Russian and Syrian warplanes continued to pound eastern and southern areas of Idlib province, according to the Syrian Observatory, a war monitor, and witnesses.

The Observatory said on Monday that pro-Damascus forces had seized control of 10 more towns in southern areas of Idlib province in less than 24 hours. It said fighting continued meanwhile around the Idlib town of Neirab between government forces and rebels backed by Turkish artillery.

"People here have little hope and everyone has started to head toward the border, fearful of the (government) advance," said Ismail Shahine, 37, originally displaced six years earlier from the Hama countryside.

Shahine on Monday prepared a tent to accommodate the rest of his family, which he said would soon arrive from the western countryside of Aleppo, where government forces have retaken large swathes of land from rebels at a rapid clip in recent weeks.

Story continues

Fearing a fresh refugee crisis, Turkey has poured thousands of troops into Idlib in the last few weeks and President Tayyip Erdogan has threatened to use military force to drive back Syrian forces unless they pull back by the end of the month.

Turkey hosts about 3.7 million Syrians and says it cannot absorb any more.

As Turkish military convoys continue to enter northern Syria, Shahine and others near the border have pinned their hopes on Erdogan's pledge to force Damascus to retreat.

"Everyone today is waiting for the start of the coming month, for the deadline that Erdogan gave the regime to withdraw," said Shahine. "I am expecting that they will make a move and not leave the Syrian people to fend for themselves."

(Reporting by Khalil Ashawi; Writing by Eric Knecht; Editing by Nick Macfie)

How to save face in Syria: Erdogan's conundrum

Ezzedine SAID,AFP•February 24, 2020

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is battling not to be the biggest loser from the Idlib campaign (AFP Photo/Mustafa Kamaci)

Istanbul (AFP) - As Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's regime presses ahead with a relentless campaign, his counterpart across the border in Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan is battling to avoid being the big loser in the battle for the last rebel bastion of Idlib.

Erdogan, who has been siding with the rebels opposing Assad, is not only facing a fierce military push by the Syrian forces. He is also having to watch a massive number of displaced people fleeing to the Turkish border while his erstwhile Russian ally, Vladimir Putin, appears to have turned his back.

This month, as many as 17 Turkish soldiers have been killed by Syrian regime forces in the northwest Idlib province and several Turkish military observation posts -- which Ankara thought were safe under deals with Russia, a key Damascus ally -- ended up being surrounded in areas retaken by the regime.

Desperate to prevent a victory by his sworn enemy Assad and a new influx of refugees swarming to Turkey's border gates, Erdogan has threatened an operation against Damascus forces unless they pull back by the end of February.

But at a time of tense relations with Putin over disagreements on Syria, a possible military campaign against the regime risks a confrontation with its guarantor Moscow -- which is for Erdogan akin to squaring the circle.

Erdogan and Putin -- the key international actors in the Syrian conflict -- signed an agreement in Sochi in 2018 establishing a "demilitarised zone" separating the regime forces from the armed opposition and jihadist groups in the Idlib province.

But the deal has been in tatters in recent weeks as Ankara and Moscow have pointed the finger of blame at each other over its failure.

- 'Direct conflict'-

"If the Assad regime fails to retreat to the previous lines at the end of the month and if Turkey and Russia fail to reach an agreement, there is a great chance that we will witness a direct conflict between Turkey and the Assad regime," Ankara-based political analyst Ali Bakeer told AFP.

"The problem for Turkey will not be the Syrian regime but the Russians," he said.

Turkey has already taken in 3.6 million Syrian refugees and has said it is unwilling to open its borders to a new wave from Idlib.

With the growing resentment toward Syrians in Turkey, officials are planning to ease the burden by settling some of them in areas now controlled by the Turkish army following three previous offensives since 2016.

"The new wave of refugee arrivals would be the worst-case scenario for Turkey, not the direct clash with Assad regime," Bakeer said.

If Turkey and Russia fail to revive the Sochi agreement, Erdogan's options are limited.

"One possible scenario is for Turkey to establish a safe zone in what would be left of Idlib and that zone would not be tied to any sort of agreements with Russia or Assad regime," said Bakeer.

Such an area would allow Turkey to house internally displaced people who fled the fighting on the Syrian territory.

- 'Strong resentment'-

"Erdogan is aware of the strong resentment in Turkey against Syrian refugees," Haid Haid, researcher at Chatham House, told AFP.

"That's why it has been framing its military activities in Idlib as a means to prevent more refugees from crossing

"The (political) cost will likely be high for him if he loses many soldiers in Syria and still fails to stop refugees from crossing to Turkey. But he might be able to gain from the crisis if the outcome of his intervention is positive."

Haid also believes that a Turkish offensive against the Syrian regime forces "is still a possibility" if political negotiations between Ankara and Moscow prove fruitless.

"Allowing Assad to capture Idlib will not only hurt Erdogan domestically, it will likely damage Turkey's reputation and its ability to project power."

For Haid, such a confrontation would not necessarily spell the end of the Turkish-Russian alliance given the burgeoning ties between the two countries in recent years especially in the fields of energy and defence.

"The current alliance between Turkey and Russia is broader than Syria," he said.

"That is why neither of them is willing, at least for now, to destroy it. Idlib is important for Turkey but it is still not considered a deal breaker."

Ezzedine SAID,AFP•February 24, 2020

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is battling not to be the biggest loser from the Idlib campaign (AFP Photo/Mustafa Kamaci)

Istanbul (AFP) - As Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's regime presses ahead with a relentless campaign, his counterpart across the border in Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan is battling to avoid being the big loser in the battle for the last rebel bastion of Idlib.

Erdogan, who has been siding with the rebels opposing Assad, is not only facing a fierce military push by the Syrian forces. He is also having to watch a massive number of displaced people fleeing to the Turkish border while his erstwhile Russian ally, Vladimir Putin, appears to have turned his back.

This month, as many as 17 Turkish soldiers have been killed by Syrian regime forces in the northwest Idlib province and several Turkish military observation posts -- which Ankara thought were safe under deals with Russia, a key Damascus ally -- ended up being surrounded in areas retaken by the regime.

Desperate to prevent a victory by his sworn enemy Assad and a new influx of refugees swarming to Turkey's border gates, Erdogan has threatened an operation against Damascus forces unless they pull back by the end of February.

But at a time of tense relations with Putin over disagreements on Syria, a possible military campaign against the regime risks a confrontation with its guarantor Moscow -- which is for Erdogan akin to squaring the circle.

Erdogan and Putin -- the key international actors in the Syrian conflict -- signed an agreement in Sochi in 2018 establishing a "demilitarised zone" separating the regime forces from the armed opposition and jihadist groups in the Idlib province.

But the deal has been in tatters in recent weeks as Ankara and Moscow have pointed the finger of blame at each other over its failure.

- 'Direct conflict'-

"If the Assad regime fails to retreat to the previous lines at the end of the month and if Turkey and Russia fail to reach an agreement, there is a great chance that we will witness a direct conflict between Turkey and the Assad regime," Ankara-based political analyst Ali Bakeer told AFP.

"The problem for Turkey will not be the Syrian regime but the Russians," he said.

Turkey has already taken in 3.6 million Syrian refugees and has said it is unwilling to open its borders to a new wave from Idlib.

With the growing resentment toward Syrians in Turkey, officials are planning to ease the burden by settling some of them in areas now controlled by the Turkish army following three previous offensives since 2016.

"The new wave of refugee arrivals would be the worst-case scenario for Turkey, not the direct clash with Assad regime," Bakeer said.

If Turkey and Russia fail to revive the Sochi agreement, Erdogan's options are limited.

"One possible scenario is for Turkey to establish a safe zone in what would be left of Idlib and that zone would not be tied to any sort of agreements with Russia or Assad regime," said Bakeer.

Such an area would allow Turkey to house internally displaced people who fled the fighting on the Syrian territory.

- 'Strong resentment'-

"Erdogan is aware of the strong resentment in Turkey against Syrian refugees," Haid Haid, researcher at Chatham House, told AFP.

"That's why it has been framing its military activities in Idlib as a means to prevent more refugees from crossing

"The (political) cost will likely be high for him if he loses many soldiers in Syria and still fails to stop refugees from crossing to Turkey. But he might be able to gain from the crisis if the outcome of his intervention is positive."

Haid also believes that a Turkish offensive against the Syrian regime forces "is still a possibility" if political negotiations between Ankara and Moscow prove fruitless.

"Allowing Assad to capture Idlib will not only hurt Erdogan domestically, it will likely damage Turkey's reputation and its ability to project power."

For Haid, such a confrontation would not necessarily spell the end of the Turkish-Russian alliance given the burgeoning ties between the two countries in recent years especially in the fields of energy and defence.

"The current alliance between Turkey and Russia is broader than Syria," he said.

"That is why neither of them is willing, at least for now, to destroy it. Idlib is important for Turkey but it is still not considered a deal breaker."

We have nothing left': displaced Syrians wait out war in Idlib

With the closed Turkish border behind them and Russian-backed forces at the horizon, Syrians have nowhere left to run

Martin Chulov Middle East correspondent Fri 21 Feb 2020

Children wait in queue to receive toys. Aid agencies say the continuous movement of people make it difficult to deliver humanitarian aid. Photograph: Burak Kara/Getty

Syrians in Idlib have implored again for international help, but that is unlikely to be forthcoming in the form of any western-backed intervention to stop the Russian-backed push. Even as the US military spokesman for the anti-Isis campaign in Syria and Iraq, Colonel Myles Caggins, called for a stop to the pro-regime offensive on Thursday, he also described Idlib as a “magnet” for extremists who are a “nuisance, menace and a threat”. The words echoed Russia’s stated views and were condemned from inside the province as “an incomplete understanding” of events.

“We are victims of the regime before anyone else,” said Rasha al-Homsi, 26. “Our lives have been reduced to labels that suit others, but don’t reflect what we suffer.”

The UN high commissioner for refugees, Filippo Grandi, made a new appeal on Thursday for those trapped in the province to be able to leave. “For these countries, already hosting 5.6 million refugees, of whom 3.6 million are in Turkey, international support must be sustained and stepped up.”

Ankara seems disinclined to open its borders again – a well-known fact to Russia, which is helping Syrian and Iranian forces on the ground. “This will all end in a deal between them both at some point,” the western diplomat said. “But I’m more worried than ever about the carnage this will leave behind and the chaos it will leave for the region and the world.”

With the closed Turkish border behind them and Russian-backed forces at the horizon, Syrians have nowhere left to run

Martin Chulov Middle East correspondent Fri 21 Feb 2020

Displaced Syrians walk on the road in Atmeh, in Idlib protectorate, the last area of Syria outside Assad’s authority. Photograph: Burak Kara/Getty

Hemmed against a border wall in Somme-like mud and misery, more than 1 million Syrians are awaiting their fate. Nearby, Iranian-backed militias and what remains of the national army are advancing towards them, as Russian jets pick them off in the crowded fields and ruined towns that are all that is left of opposition-held Syria.

Convoys of the Turkish military, a protector of the displaced that have made it to the province over the last eight years, pass regularly along roads teeming with clapped out cars full of families and remnants of their belongings. Women and children beg them to stop, but they continue on to battlefronts miles from the panic and confusion, their attention diverted from helping the destitute to shaping the final months of the war in Ankara’s interests. Aid workers, who say things have never been worse in Syria, do what they can among scenes they describe as overwhelming and impossible.

Over eight years of slaughter and displacement, the Turks had been the protectors of many people in Idlib – the last part of the war-torn country to remain outside of central government authority – their sole insurance against a final onslaught long considered inevitable and which was launched in mid-January by a conglomerate of forces supporting the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, all bent on retaking control.

A Syrian family ride in the back of a truck as up to 1 million civilians have been displaced by fighting in Idlib since December. Photograph: Burak Kara/Getty

Even in a war that has known few boundaries, the last month of brutality has been almost without precedent. Up to 1 million people are again on the move in Idlib. With the Turkish frontier behind them and an ascendant, vengeful foe over the horizon, they have nowhere left to run or hide.

Across the sodden, chaotic plains of the northwestern province, in the newly energised Russian war rooms, and among European diplomats that have failed to steer the war towards a diplomatic end, a realisation is growing that, one way or another, the most devastating conflict of modern times is grinding to a close. Its cost will be enormous, and will likely be paid over many continents and several generations. But first the people of Idlib need help and aid agencies say it has never been harder to deliver.

Syria: the fight for Idlib

“It’s not just the mind-boggling number of people in need of critical help, but the fact they are constantly moving,” said the Syria director of Mercy Corps, Kieren Barnes. “It’s next to impossible to preposition the quantity of supplies needed. If the fighting doesn’t stop soon, we have to face the terrible reality that our teams may not be able to reach those most at risk.”

A Mercy Corps worker inside Idlib said: “There is panic, confusion and a sense of loss. Many feel like this is the end of the road. I have never seen anything like this.”

Ahmed Naddour, who is now living in a makeshift tent near the border with six family members after four years of the moves that included Damascus, west Aleppo and the far north of Idlib, said: “Everywhere we could have sheltered has been levelled by the Russians. This is it for us. We have nothing left, and I have not admitted that to myself at any point since 2011.”

Nearby are displaced people from all over Syria: Homs, where the uprising began in 2011; Ghouta, where it was crushed by poison gas in 2013; and Aleppo, whose fall in 2016 marked a change in Ankara’s broad support for the anti-Assad opposition and a turning point in the course of the war.

Through it all, Idlib has been a last redoubt, a place where all comers could seek refuge from pro-regime forces, but at the price of living among extremist groups that had been there before and taken instrumental roles in most aspects of civic life across large parts of the province.

The aegis of extremists, including global jihadists, has been an intractable problem for nationalist opposition groups in Idlib that had received Turkish and, until early 2018, western backing in their fight against Assad. Both sides had accommodated each other in earlier clashes and as the final battle drew nearer.

The presence of extremists had been central to the Syrian narrative that all those opposing it were terrorists from the outset. Large numbers of exiles had been sent to Idlib as part of surrender deals negotiated with vanquished opposition communities and forced to co-exist with extremists. The fear that this would dehumanise an entire population of at least 3.5 million people, 80% of which, according to UN estimates, is made up of women and children, has been borne out in the eyes of international observers.

“Yes, there is fatigue about Syria and war in the region in general,” said a regional diplomat. “But this is one of the gravest crises of our lifetimes. They have created a kill box in Idlib and no-one cares about that.”

Hemmed against a border wall in Somme-like mud and misery, more than 1 million Syrians are awaiting their fate. Nearby, Iranian-backed militias and what remains of the national army are advancing towards them, as Russian jets pick them off in the crowded fields and ruined towns that are all that is left of opposition-held Syria.

Convoys of the Turkish military, a protector of the displaced that have made it to the province over the last eight years, pass regularly along roads teeming with clapped out cars full of families and remnants of their belongings. Women and children beg them to stop, but they continue on to battlefronts miles from the panic and confusion, their attention diverted from helping the destitute to shaping the final months of the war in Ankara’s interests. Aid workers, who say things have never been worse in Syria, do what they can among scenes they describe as overwhelming and impossible.

Over eight years of slaughter and displacement, the Turks had been the protectors of many people in Idlib – the last part of the war-torn country to remain outside of central government authority – their sole insurance against a final onslaught long considered inevitable and which was launched in mid-January by a conglomerate of forces supporting the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, all bent on retaking control.

A Syrian family ride in the back of a truck as up to 1 million civilians have been displaced by fighting in Idlib since December. Photograph: Burak Kara/Getty

Even in a war that has known few boundaries, the last month of brutality has been almost without precedent. Up to 1 million people are again on the move in Idlib. With the Turkish frontier behind them and an ascendant, vengeful foe over the horizon, they have nowhere left to run or hide.

Across the sodden, chaotic plains of the northwestern province, in the newly energised Russian war rooms, and among European diplomats that have failed to steer the war towards a diplomatic end, a realisation is growing that, one way or another, the most devastating conflict of modern times is grinding to a close. Its cost will be enormous, and will likely be paid over many continents and several generations. But first the people of Idlib need help and aid agencies say it has never been harder to deliver.

Syria: the fight for Idlib

“It’s not just the mind-boggling number of people in need of critical help, but the fact they are constantly moving,” said the Syria director of Mercy Corps, Kieren Barnes. “It’s next to impossible to preposition the quantity of supplies needed. If the fighting doesn’t stop soon, we have to face the terrible reality that our teams may not be able to reach those most at risk.”

A Mercy Corps worker inside Idlib said: “There is panic, confusion and a sense of loss. Many feel like this is the end of the road. I have never seen anything like this.”

Ahmed Naddour, who is now living in a makeshift tent near the border with six family members after four years of the moves that included Damascus, west Aleppo and the far north of Idlib, said: “Everywhere we could have sheltered has been levelled by the Russians. This is it for us. We have nothing left, and I have not admitted that to myself at any point since 2011.”

Nearby are displaced people from all over Syria: Homs, where the uprising began in 2011; Ghouta, where it was crushed by poison gas in 2013; and Aleppo, whose fall in 2016 marked a change in Ankara’s broad support for the anti-Assad opposition and a turning point in the course of the war.

Through it all, Idlib has been a last redoubt, a place where all comers could seek refuge from pro-regime forces, but at the price of living among extremist groups that had been there before and taken instrumental roles in most aspects of civic life across large parts of the province.

The aegis of extremists, including global jihadists, has been an intractable problem for nationalist opposition groups in Idlib that had received Turkish and, until early 2018, western backing in their fight against Assad. Both sides had accommodated each other in earlier clashes and as the final battle drew nearer.

The presence of extremists had been central to the Syrian narrative that all those opposing it were terrorists from the outset. Large numbers of exiles had been sent to Idlib as part of surrender deals negotiated with vanquished opposition communities and forced to co-exist with extremists. The fear that this would dehumanise an entire population of at least 3.5 million people, 80% of which, according to UN estimates, is made up of women and children, has been borne out in the eyes of international observers.

“Yes, there is fatigue about Syria and war in the region in general,” said a regional diplomat. “But this is one of the gravest crises of our lifetimes. They have created a kill box in Idlib and no-one cares about that.”

Children wait in queue to receive toys. Aid agencies say the continuous movement of people make it difficult to deliver humanitarian aid. Photograph: Burak Kara/Getty

Syrians in Idlib have implored again for international help, but that is unlikely to be forthcoming in the form of any western-backed intervention to stop the Russian-backed push. Even as the US military spokesman for the anti-Isis campaign in Syria and Iraq, Colonel Myles Caggins, called for a stop to the pro-regime offensive on Thursday, he also described Idlib as a “magnet” for extremists who are a “nuisance, menace and a threat”. The words echoed Russia’s stated views and were condemned from inside the province as “an incomplete understanding” of events.

“We are victims of the regime before anyone else,” said Rasha al-Homsi, 26. “Our lives have been reduced to labels that suit others, but don’t reflect what we suffer.”

The UN high commissioner for refugees, Filippo Grandi, made a new appeal on Thursday for those trapped in the province to be able to leave. “For these countries, already hosting 5.6 million refugees, of whom 3.6 million are in Turkey, international support must be sustained and stepped up.”

Ankara seems disinclined to open its borders again – a well-known fact to Russia, which is helping Syrian and Iranian forces on the ground. “This will all end in a deal between them both at some point,” the western diplomat said. “But I’m more worried than ever about the carnage this will leave behind and the chaos it will leave for the region and the world.”

No comments:

Post a Comment