1/14/21

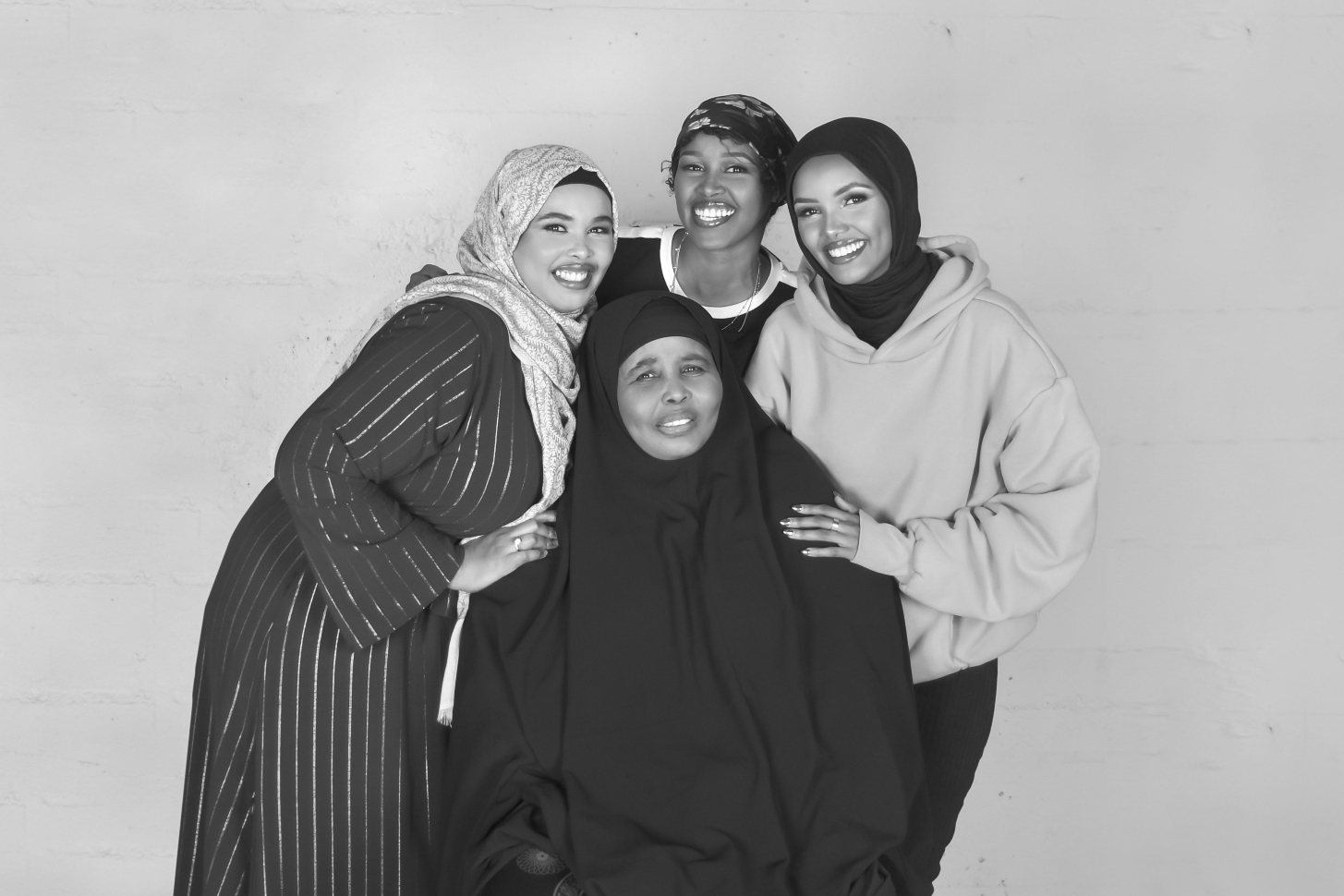

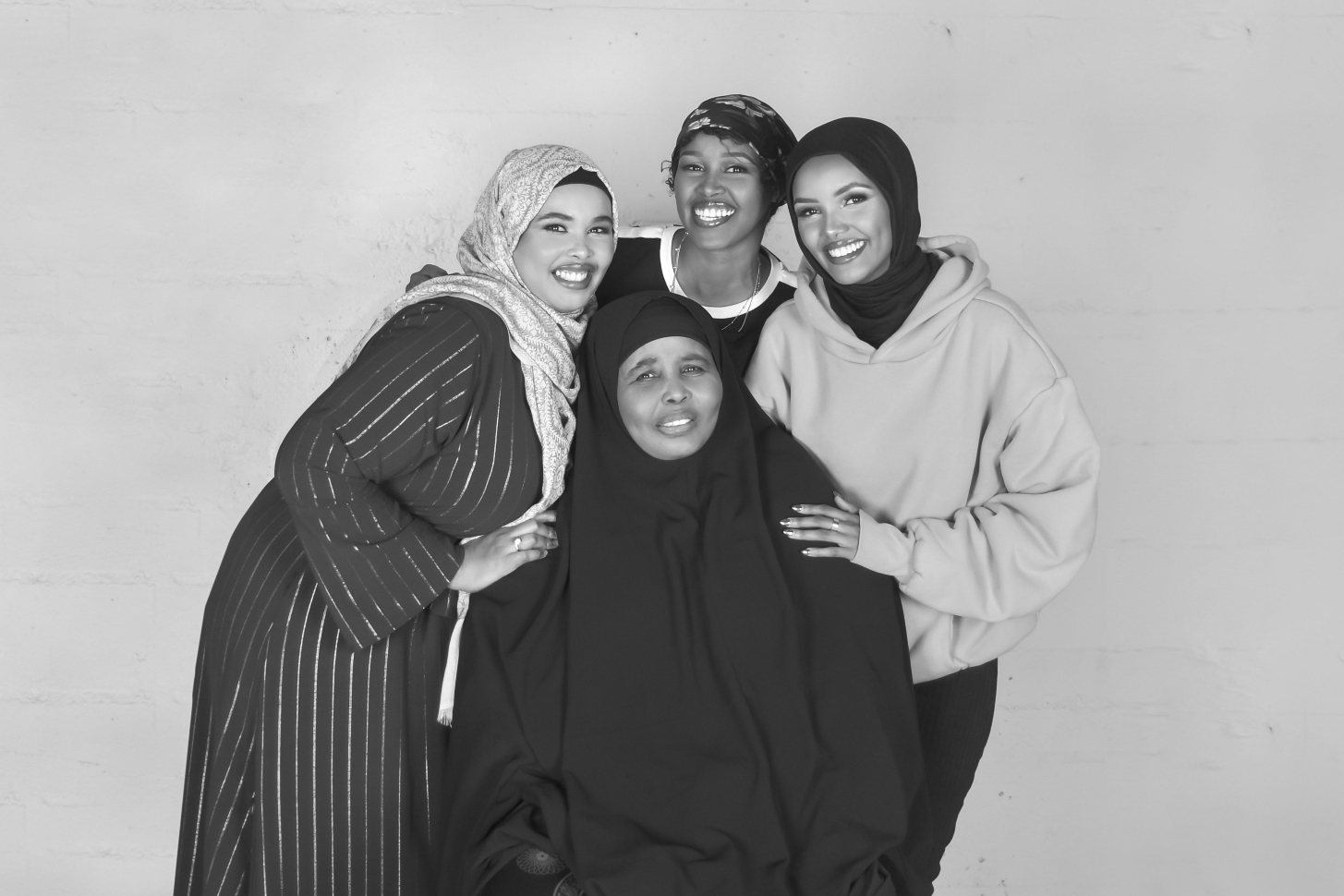

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGILIANE MANSFELDT PHOTOGRAPHY

Halima Aden, the first hijab-wearing supermodel, quit the fashion industry in November saying it was incompatible with her Muslim religion. Here, in an exclusive interview, she tells BBC Global Religion reporter Sodaba Haidare the full story - how she became a model, and how she reached the decision to walk away.

Halima, 23, is in St Cloud, Minnesota, where she grew up surrounded by other Somalis. She's wearing ordinary clothes and no makeup, cheerfully petting her dog, Coco.

"I'm Halima from Kakuma," she says, referring to the refugee camp in Kenya, where she was born. Others have described her as a trailblazing hijab-wearing supermodel or as the first hijabi model to feature on the cover of Vogue magazine - but she left all that behind two months ago, saying the fashion industry clashed with her Muslim faith.

"It's the most comfortable I've ever felt in an interview," she laughs. "Because I didn't spend 10 hours getting ready, in an outfit I couldn't keep."

As a hijab-wearing model, Halima was selective about her clothing. At the start of her career, she would take a suitcase filled with her own hijabs, long dresses and skirts to every shoot. She wore her own plain black hijab for her first campaign for Rihanna's Fenty Beauty.

However she was dressed, keeping her hijab on for every shoot was non-negotiable. It was so important to her that in 2017 when she signed with IMG, one of the biggest modelling agencies in the world, she added a clause to her contract making IMG agree that she would never have to remove it. Her hijab meant the world to her.

Halima Aden, the first hijab-wearing supermodel, quit the fashion industry in November saying it was incompatible with her Muslim religion. Here, in an exclusive interview, she tells BBC Global Religion reporter Sodaba Haidare the full story - how she became a model, and how she reached the decision to walk away.

Halima, 23, is in St Cloud, Minnesota, where she grew up surrounded by other Somalis. She's wearing ordinary clothes and no makeup, cheerfully petting her dog, Coco.

"I'm Halima from Kakuma," she says, referring to the refugee camp in Kenya, where she was born. Others have described her as a trailblazing hijab-wearing supermodel or as the first hijabi model to feature on the cover of Vogue magazine - but she left all that behind two months ago, saying the fashion industry clashed with her Muslim faith.

"It's the most comfortable I've ever felt in an interview," she laughs. "Because I didn't spend 10 hours getting ready, in an outfit I couldn't keep."

As a hijab-wearing model, Halima was selective about her clothing. At the start of her career, she would take a suitcase filled with her own hijabs, long dresses and skirts to every shoot. She wore her own plain black hijab for her first campaign for Rihanna's Fenty Beauty.

However she was dressed, keeping her hijab on for every shoot was non-negotiable. It was so important to her that in 2017 when she signed with IMG, one of the biggest modelling agencies in the world, she added a clause to her contract making IMG agree that she would never have to remove it. Her hijab meant the world to her.

GETTY IMAGES Halima modelling for Max Mara in February 2017

"There are girls who wanted to die for a modelling contract," she says, "but I was ready to walk away if it wasn't accepted."

This was despite the fact that at that stage no-one had heard of her - that she was "a nobody".

But as time went on she had less control over the clothes she wore, and agreed to head coverings she would have ruled out at the start.

"I eventually drifted away and got into the confusing grey area of letting the team on-set style my hijab."

In the last year of her career her hijab got smaller and smaller, sometimes accentuating her neck and chest. And sometimes instead of the hijab, she wrapped jeans, or other clothes and fabrics, around her head.

GETTY IMAGES On the runway for Tommy Hilfiger London Spring 2020

Another clause of Halima's contract guaranteed her a blocked-out box, allowing her to get dressed in the privacy of her own space.

But she soon realised that other hijab-wearing models, who had followed her into the industry, were not being treated with the same respect. She would see them being told to find a bathroom to change in.

"That rubbed me the wrong way and I was like, 'OMG, these girls are following in my footsteps, and I have opened the door to the lion's mouth.'"

She had expected her successors to be her equals, and this intensified her protective feelings towards them.

"A lot of them are so young, it can be a creepy industry. Even the parties that we attended, I would always find myself in big sister mode having to grab one of the hijab-wearing models because she'd be surrounded by a group of men following and flocking [round] her. I was like, 'This doesn't look right, she's a child.' I would pull her out and ask her who she was with."

Part of this sense of responsibility and community comes from Halima's Somali background.

As a child in Kakuma refugee camp, in north-western Kenya, she was taught by her mother to work hard and to help others. And this continued after they moved to Minnesota, when Halima was seven, becoming part of the largest Somali community in the US.

So there was a problem when Halima became her high school's first hijab-wearing homecoming queen (an honour bestowed on the school's most popular students). She knew her mum, whose focus was on good grades, would disapprove.

"I was so embarrassed, because when you get nominated, the kids come to your house and I said, 'Don't do that - my mum will have the shoe ready and you wouldn't know what you've gotten yourselves into!'"

Her fears were justified. Halima's mum broke the homecoming crown. "You're focusing way too much on friends and beauty pageants," she said.

But Halima still took part in Miss Minnesota USA in 2016. She was the first hijab-wearing contestant and became a semi-finalist.

Another clause of Halima's contract guaranteed her a blocked-out box, allowing her to get dressed in the privacy of her own space.

But she soon realised that other hijab-wearing models, who had followed her into the industry, were not being treated with the same respect. She would see them being told to find a bathroom to change in.

"That rubbed me the wrong way and I was like, 'OMG, these girls are following in my footsteps, and I have opened the door to the lion's mouth.'"

She had expected her successors to be her equals, and this intensified her protective feelings towards them.

"A lot of them are so young, it can be a creepy industry. Even the parties that we attended, I would always find myself in big sister mode having to grab one of the hijab-wearing models because she'd be surrounded by a group of men following and flocking [round] her. I was like, 'This doesn't look right, she's a child.' I would pull her out and ask her who she was with."

Part of this sense of responsibility and community comes from Halima's Somali background.

As a child in Kakuma refugee camp, in north-western Kenya, she was taught by her mother to work hard and to help others. And this continued after they moved to Minnesota, when Halima was seven, becoming part of the largest Somali community in the US.

So there was a problem when Halima became her high school's first hijab-wearing homecoming queen (an honour bestowed on the school's most popular students). She knew her mum, whose focus was on good grades, would disapprove.

"I was so embarrassed, because when you get nominated, the kids come to your house and I said, 'Don't do that - my mum will have the shoe ready and you wouldn't know what you've gotten yourselves into!'"

Her fears were justified. Halima's mum broke the homecoming crown. "You're focusing way too much on friends and beauty pageants," she said.

But Halima still took part in Miss Minnesota USA in 2016. She was the first hijab-wearing contestant and became a semi-finalist.

ALAMY Competing in the Miss Minnesota pageant in 2016

And then, to her mother's dismay, Halima chose to pursue a career in modelling - a career her mother felt was in conflict with who Halima was as a person: black, Muslim, refugee.

Even when she started walking on some of the world's major runways for Yeezy and Max Mara, or became a Miss USA judge, her mother still encouraged her to "get a proper job".

It was the humanitarian side of Halima's career that had gone some way to convincing her mother that it was worth it. As a refugee who had walked 12 days from Somalia to Kenya for a better life, she knew the value of helping those in need.

"She said, 'There's no way you'll do modelling if it doesn't have a giving-back component.' In my first meeting with IMG I told them to take me to Unicef," Halima says.

And then, to her mother's dismay, Halima chose to pursue a career in modelling - a career her mother felt was in conflict with who Halima was as a person: black, Muslim, refugee.

Even when she started walking on some of the world's major runways for Yeezy and Max Mara, or became a Miss USA judge, her mother still encouraged her to "get a proper job".

It was the humanitarian side of Halima's career that had gone some way to convincing her mother that it was worth it. As a refugee who had walked 12 days from Somalia to Kenya for a better life, she knew the value of helping those in need.

"She said, 'There's no way you'll do modelling if it doesn't have a giving-back component.' In my first meeting with IMG I told them to take me to Unicef," Halima says.

GETTY IMAGES

IMG supported her in this and in 2018 Halima became a Unicef ambassador. As she had spent her childhood in a refugee camp, her work focused on children's rights.

"My mum never viewed me as a model or cover girl. She viewed me as a beacon of hope for young girls and would always remind me to be a good role model for them."

Halima wanted to raise awareness about displaced children, and to show the children that if she could make it out of the refugee camp, they could hope to one day do the same.

But Unicef didn't live up to her expectations.

In 2018, not long after becoming a Unicef ambassador, she visited the Kakuma camp to give a Ted Talk.

"I met with the kids and asked them, 'Are things still being done the way they were, do you still have to dance and sing in front of newcomers?' They said, 'Yes, but this time we're not doing it for other celebrities they'd bring to the camp, this time we're doing it for you.'"

Halima was guilt-stricken and upset. She says she still remembers when she and other children sang and danced for visiting celebrities.

"The UN workers prepped me for what was to come: I had my first headshot, thanks to those organisations."

IMG supported her in this and in 2018 Halima became a Unicef ambassador. As she had spent her childhood in a refugee camp, her work focused on children's rights.

"My mum never viewed me as a model or cover girl. She viewed me as a beacon of hope for young girls and would always remind me to be a good role model for them."

Halima wanted to raise awareness about displaced children, and to show the children that if she could make it out of the refugee camp, they could hope to one day do the same.

But Unicef didn't live up to her expectations.

In 2018, not long after becoming a Unicef ambassador, she visited the Kakuma camp to give a Ted Talk.

"I met with the kids and asked them, 'Are things still being done the way they were, do you still have to dance and sing in front of newcomers?' They said, 'Yes, but this time we're not doing it for other celebrities they'd bring to the camp, this time we're doing it for you.'"

Halima was guilt-stricken and upset. She says she still remembers when she and other children sang and danced for visiting celebrities.

"The UN workers prepped me for what was to come: I had my first headshot, thanks to those organisations."

GETTY IMAGES Sudanese refugees dancing at Kakuma refugee camp

It seemed to her that the organisation focused more on its brand than on children's education.

"I could spell 'Unicef' when I couldn't spell my own name. I was marking X," she says. "Minnesota gave me my first book, my first pencil, my first backpack. Not Unicef."

She had assumed all of that had changed since she left.

In November, when she video-called the kids in Kakuma for World Children's Day, she decided she couldn't carry on. It was hard to see them in winter in the middle of a global pandemic.

"After speaking to the kids, I had a breakthrough," she says.

"I just decided I'm done with the NGO world using me for 'my beautiful story of courage and hope'"

Unicef USA told the BBC: "We are grateful for [Halima's] three-and-a-half years of partnership and support. Her remarkable story of resilience and hope has guided her vision for a world that upholds the rights of every child. It has been a privilege for Unicef to work with Halima and we wish her all the best in her future endeavours."

Halima's doubts about the modelling side of her career had also been multiplying.

As demand for her in the fashion industry grew, she spent less time with her family and would be away from home on Muslim religious festivals.

"In the first year of my career I was able to make it home for Eid and Ramadan but in the last three years, I was travelling. I was sometimes on six to seven flights a week. It just didn't pause," she says.

GETTY IMAGES Halima Aden watching a model wearing clothes designed by Sherri Hill

In September 2019, she was featured on the cover of King Kong magazine, wearing bright red and green eye shadow and a large piece of jewellery on her face. It resembled a mask and covered everything but her nose and mouth.

"The style and makeup were horrendous. I looked like a white man's fetishised version of me," she says.

And to her horror, she found a picture of a nude man in the same issue.

"Why would the magazine think it was acceptable to have a hijab-wearing Muslim woman when a naked man is on the next page?" she asks. It went against everything she believed in.

King Kong told the BBC: "The artists, photographers and contributors with whom we work express themselves in ways which may both appeal to some and seem provocative to others, but the stories they produce always respect the subject and the model.

In September 2019, she was featured on the cover of King Kong magazine, wearing bright red and green eye shadow and a large piece of jewellery on her face. It resembled a mask and covered everything but her nose and mouth.

"The style and makeup were horrendous. I looked like a white man's fetishised version of me," she says.

And to her horror, she found a picture of a nude man in the same issue.

"Why would the magazine think it was acceptable to have a hijab-wearing Muslim woman when a naked man is on the next page?" she asks. It went against everything she believed in.

King Kong told the BBC: "The artists, photographers and contributors with whom we work express themselves in ways which may both appeal to some and seem provocative to others, but the stories they produce always respect the subject and the model.

"We are sorry that Halima now regrets the work she did with us, and that there were images in the issue that she personally did not like, but were in no way connected to her own feature."

Halima says that when she spotted her photograph on the cover of magazines at airports, as she travelled between shoots, she would often barely recognise herself.

ALAMY

"I had zero excitement because I couldn't see myself. Do you know how mentally damaging that can be to be to somebody? When I'm supposed to feel happy and grateful and I'm supposed to relate, because that's me, that's my own picture, but I was so far removed.

"My career was seemingly on top, but I was mentally not happy."

And there were those other problems - her hijab rule getting stretched to breaking point, and the way other hijab-wearing models were being treated.

The coronavirus pandemic put everything in perspective. With Covid-19 halting fashion shoots and runway shows, she returned home to St Cloud to spend time with her mother, to whom she remains incredibly close.

"I was having anxiety thinking of 2021 because I loved staying at home with my family and seeing friends again," she says.

All this explains why, in November, she decided to give up both modelling and her role with Unicef.

"I'm grateful for this new chance that Covid gave me. We're all reflecting about our career paths and asking, 'Does it bring me genuine happiness, does it bring me joy?'" she says.

Her mother's prayers had finally been granted. She was so elated she even agreed to do a photoshoot with her daughter, just for fun.

"When I was a model, my mum turned down every shoot, she wouldn't even do mother-daughter campaigns. I wanted to give her a chance to see me in my creative zone," says Halima excitedly.

"She really is my number one inspiration and I'm so grateful God picked me to be her daughter. She's truly a remarkable and resilient woman."

"I had zero excitement because I couldn't see myself. Do you know how mentally damaging that can be to be to somebody? When I'm supposed to feel happy and grateful and I'm supposed to relate, because that's me, that's my own picture, but I was so far removed.

"My career was seemingly on top, but I was mentally not happy."

And there were those other problems - her hijab rule getting stretched to breaking point, and the way other hijab-wearing models were being treated.

The coronavirus pandemic put everything in perspective. With Covid-19 halting fashion shoots and runway shows, she returned home to St Cloud to spend time with her mother, to whom she remains incredibly close.

"I was having anxiety thinking of 2021 because I loved staying at home with my family and seeing friends again," she says.

All this explains why, in November, she decided to give up both modelling and her role with Unicef.

"I'm grateful for this new chance that Covid gave me. We're all reflecting about our career paths and asking, 'Does it bring me genuine happiness, does it bring me joy?'" she says.

Her mother's prayers had finally been granted. She was so elated she even agreed to do a photoshoot with her daughter, just for fun.

"When I was a model, my mum turned down every shoot, she wouldn't even do mother-daughter campaigns. I wanted to give her a chance to see me in my creative zone," says Halima excitedly.

"She really is my number one inspiration and I'm so grateful God picked me to be her daughter. She's truly a remarkable and resilient woman."

GILIANE MANSFELDT PHOTOGRAPHY

Halima with her mother, sister Fadumo (left) and cousin Rahma

The photoshoot is not the only thing Halima is excited about. She has just finished executive-producing a film inspired by the true story of a refugee fleeing war and violence in Afghanistan. I Am You is due to be released on Apple TV in March.

"We're anxiously waiting to see if we've been nominated for an Oscar!" she says.

Quitting Unicef doesn't mean Halima has given up doing charity work.

"I'm not going to stop volunteering," she says. "I don't think the world needs me as a model or celebrity, it needs me as Halima from Kakuma - somebody who understands the true value of a penny and the true value of community."

But first she is going to take a break.

"You know, I've never been on a proper vacation. I'm putting my mental health and my family at the top. I'm thriving, not just surviving. I'm getting my mental health checked, I'm getting therapy time."

The photoshoot is not the only thing Halima is excited about. She has just finished executive-producing a film inspired by the true story of a refugee fleeing war and violence in Afghanistan. I Am You is due to be released on Apple TV in March.

"We're anxiously waiting to see if we've been nominated for an Oscar!" she says.

Quitting Unicef doesn't mean Halima has given up doing charity work.

"I'm not going to stop volunteering," she says. "I don't think the world needs me as a model or celebrity, it needs me as Halima from Kakuma - somebody who understands the true value of a penny and the true value of community."

But first she is going to take a break.

"You know, I've never been on a proper vacation. I'm putting my mental health and my family at the top. I'm thriving, not just surviving. I'm getting my mental health checked, I'm getting therapy time."

No comments:

Post a Comment