Lush Caribbean tourist islands poisoned workers for decades with banned pesticide, protesters say

Shari Kulha 3/2/2021

Streets and parks were crowded on the French island of Martinique over the weekend as thousands of residents protested the government’s lack of progress on a compensation bid over the harm done by a program of using a highly toxic insecticide on banana plantations.

Provided by National Post Several thousand people demonstrate in Fort-de-France, Martinique, on Feb. 27, 2021 against the government's lack of care over the after-effects of chlordecone, an insecticide accused of having poisoned the French West Indies island.

From 1972 to 1993, chlordecone was used to protect the crop from bugs — but protest organizers say its damaging effects on humans had been known as early as the 1960s. Even though the chemical, related to DDT, was finally banned in 1990, growers lobbied for and were granted permission to use up stocks until 1993.

It was authorized for use in the French West Indies well after its harmful effects were known and for more than 20 years after it was banned. And now, the French public health agency notes , 92 per cent of the adult population of Martinique has chlordecone in their blood — and the tropical island has one of the highest rates of prostate cancer in the world.

Here’s Aljazeera’s account of the issue:

From 1972 to 1993, chlordecone was used to protect the crop from bugs — but protest organizers say its damaging effects on humans had been known as early as the 1960s. Even though the chemical, related to DDT, was finally banned in 1990, growers lobbied for and were granted permission to use up stocks until 1993.

It was authorized for use in the French West Indies well after its harmful effects were known and for more than 20 years after it was banned. And now, the French public health agency notes , 92 per cent of the adult population of Martinique has chlordecone in their blood — and the tropical island has one of the highest rates of prostate cancer in the world.

Here’s Aljazeera’s account of the issue:

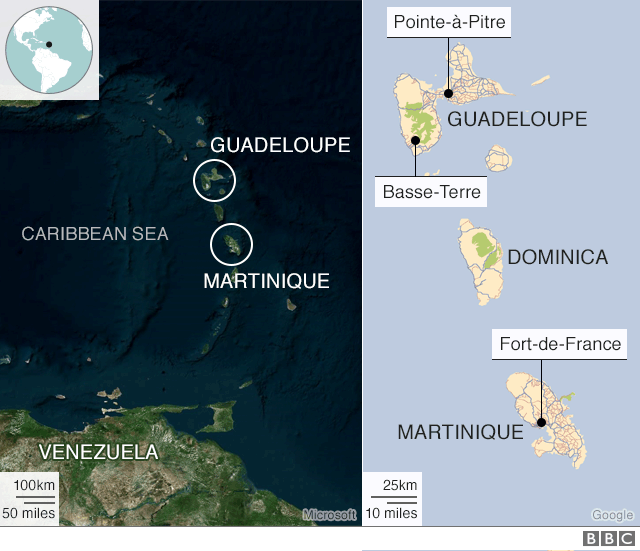

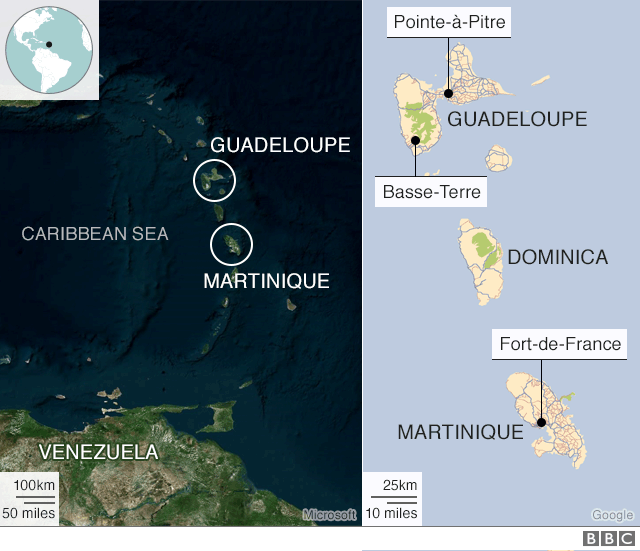

Organizations on Martinique and its neighbouring island, Guadeloupe, both French territories, filed a legal complaint over the issue in 2006, which triggered an investigation in 2008.

Production of chlordecone had been stopped in the United States — where it was marketed as Kepone — as far back as 1975, after workers at a factory producing it in Virginia complained of uncontrollable shaking, blurred vision and sexual problems. In 1979, the World Health Organization classed the pesticide, an endocrine disruptor, as potentially carcinogenic.

Chlordecone was then banned worldwide by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2009

© Lionel Chamoiseau / AFP Getty This placard in Saturday’s demonstration shows a number of bananas, like fingers, clutching at a man’s throat as if to strangle him.

“They used to tell us: don’t eat or drink anything while you’re putting it down,” Ambroise Bertin, now 70, told the BBC . Few, if any, were told to wear gloves or masks. For decades, he says the workers were told nothing else about it. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Up to 15,000 people, according to organizers (5,000 according to police), marched through the capital, Fort-de-France, on Saturday, precipitated by a judge’s statement in Paris earlier this year that said the case may fall under French statute of limitation rules, which would make it impossible to pursue action.

“Thousands are mobilized to respond to that gob of spit the French state is sending us, the statute of limitations,” said Francis Carole, a Martinican politician.

“They used to tell us: don’t eat or drink anything while you’re putting it down,” Ambroise Bertin, now 70, told the BBC . Few, if any, were told to wear gloves or masks. For decades, he says the workers were told nothing else about it. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Up to 15,000 people, according to organizers (5,000 according to police), marched through the capital, Fort-de-France, on Saturday, precipitated by a judge’s statement in Paris earlier this year that said the case may fall under French statute of limitation rules, which would make it impossible to pursue action.

“Thousands are mobilized to respond to that gob of spit the French state is sending us, the statute of limitations,” said Francis Carole, a Martinican politician.

© Lionel Chamoiseau / AFP Getty Protesters crowd a park in Fort-de-France, Martinique, on Feb. 27, 2021 to vent anger over the possibility of not being able sue for damage to their health.

In 2018, President Emmanuel Macron accepted the state’s responsibility for what he called “an environmental scandal,” the BBC reported. He said France had suffered “collective blindness” over the issue. A law to create a compensation fund for agricultural workers has now been passed but payouts are yet to begin.

“The government pretended to accept legal action but did nothing, except wash its hands of this bit by bit,” said Harry Bauchaint, a member of the Peyi-A political movement.

One of the world’s leading experts on chlordecone, Prof. Luc Multigner, of Rennes University in France, told the BBC original documents of the official body that authorized use of the pesticide in 1981 have disappeared, hampering the investigation into how the decision was made.

In Guadeloupe on Saturday, some 300 people demonstrated as well, while 200 protested in Paris.

“The entire French population should mobilize to make sure the statute of limitations doesn’t apply,” Toni Mango, head of the Kolektif Doubout Pou Gwadloup association, told AFP.

Bananas and other tree fruits are said to be safe now but vegetables can’t yet be grown. Some say it will take hundreds of years for the land and waters to be free of the contamination.

Ambroise Bertin, who now also suffers from thyroid problems, said “they never told us it was dangerous.”

In 2018, President Emmanuel Macron accepted the state’s responsibility for what he called “an environmental scandal,” the BBC reported. He said France had suffered “collective blindness” over the issue. A law to create a compensation fund for agricultural workers has now been passed but payouts are yet to begin.

“The government pretended to accept legal action but did nothing, except wash its hands of this bit by bit,” said Harry Bauchaint, a member of the Peyi-A political movement.

One of the world’s leading experts on chlordecone, Prof. Luc Multigner, of Rennes University in France, told the BBC original documents of the official body that authorized use of the pesticide in 1981 have disappeared, hampering the investigation into how the decision was made.

In Guadeloupe on Saturday, some 300 people demonstrated as well, while 200 protested in Paris.

“The entire French population should mobilize to make sure the statute of limitations doesn’t apply,” Toni Mango, head of the Kolektif Doubout Pou Gwadloup association, told AFP.

Bananas and other tree fruits are said to be safe now but vegetables can’t yet be grown. Some say it will take hundreds of years for the land and waters to be free of the contamination.

Ambroise Bertin, who now also suffers from thyroid problems, said “they never told us it was dangerous.”

Pesticide poisoned French paradise islands in Caribbean

By Laurence Peter

BBC News

Published25 October 2019

By Laurence Peter

BBC News

Published25 October 2019

Bananas are a big export industry for Martinique and nearly all are shipped to France

The French Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique thrive on their image as idyllic sun, sea and sand destinations for tourists.

But few visitors are aware that these lush, tropical islands have a chronic pollution problem.

A pesticide linked to cancer - chlordecone - was sprayed on banana crops on the islands for two decades and now nearly all the adult local residents have traces of it in their blood.

French President Emmanuel Macron has called it an "environmental scandal" and said the state "must take responsibility". He visited Martinique last year and was briefed on the crisis on the islands, known in France as the Antilles.

The French parliament is holding a public inquiry which will report its findings in December.

"We found anger and anxiety in the Antilles - the population feel abandoned by the republic," said Guadeloupe MP Justine Benin, who is in charge of the inquiry's report.

"They are resilient people, they've been hit by hurricanes before, but their trust needs to be restored," she told the BBC.

Large tracts of soil are contaminated, as are rivers and coastal waters. The authorities are trying to keep the chemical out of the food chain, but it is difficult, as much produce comes from smallholders, often sold at the roadside.

The French Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique thrive on their image as idyllic sun, sea and sand destinations for tourists.

But few visitors are aware that these lush, tropical islands have a chronic pollution problem.

A pesticide linked to cancer - chlordecone - was sprayed on banana crops on the islands for two decades and now nearly all the adult local residents have traces of it in their blood.

French President Emmanuel Macron has called it an "environmental scandal" and said the state "must take responsibility". He visited Martinique last year and was briefed on the crisis on the islands, known in France as the Antilles.

The French parliament is holding a public inquiry which will report its findings in December.

"We found anger and anxiety in the Antilles - the population feel abandoned by the republic," said Guadeloupe MP Justine Benin, who is in charge of the inquiry's report.

"They are resilient people, they've been hit by hurricanes before, but their trust needs to be restored," she told the BBC.

Large tracts of soil are contaminated, as are rivers and coastal waters. The authorities are trying to keep the chemical out of the food chain, but it is difficult, as much produce comes from smallholders, often sold at the roadside.

Grande Anse des Salines, Martinique: Tourism is the island's biggest foreign exchange earner

Drinking water is considered safe, as carbon filters are used to remove contaminants.

In the US a factory producing chlordecone - sold commercially as kepone - was shut down in 1975 after workers fell seriously ill there. But Antilles banana growers continued to use the pesticide.

What is chlordecone?

It is a chlorinated chemical similar to DDT, and an endocrine disruptor - meaning it can interfere with hormones and cause disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as "potentially carcinogenic". It causes liver tumours in lab mice.

Banana plantations in the Antilles used it to eradicate root borers - weevils that attack banana plants.

Chlordecone was already recognised as hazardous in 1972. It was banned in the US as kepone after several hundred workers were contaminated at a factory in Hopewell, Virginia, in 1975. Their symptoms included nervous tremors, slurred speech, short-term memory loss and low sperm counts.

As French agriculture minister in 1972 Jacques Chirac, who later became president, authorised chlordecone as a pesticide.

It was not banned in the Antilles until 1993 - a delay attributed to lobbying pressure from banana growers.

Drinking water is considered safe, as carbon filters are used to remove contaminants.

In the US a factory producing chlordecone - sold commercially as kepone - was shut down in 1975 after workers fell seriously ill there. But Antilles banana growers continued to use the pesticide.

What is chlordecone?

It is a chlorinated chemical similar to DDT, and an endocrine disruptor - meaning it can interfere with hormones and cause disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as "potentially carcinogenic". It causes liver tumours in lab mice.

Banana plantations in the Antilles used it to eradicate root borers - weevils that attack banana plants.

Chlordecone was already recognised as hazardous in 1972. It was banned in the US as kepone after several hundred workers were contaminated at a factory in Hopewell, Virginia, in 1975. Their symptoms included nervous tremors, slurred speech, short-term memory loss and low sperm counts.

As French agriculture minister in 1972 Jacques Chirac, who later became president, authorised chlordecone as a pesticide.

It was not banned in the Antilles until 1993 - a delay attributed to lobbying pressure from banana growers.

A Guadeloupe banana plantation - the fruit itself is not contaminated

The chemical is very slow to break down in the environment: contamination can persist for centuries, experts say.

It was restricted globally under the Stockholm Convention in 2016, along with 25 other "Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)".

How big is the problem?

"The economic impact is enormous," says Prof Luc Multigner, head of research at Inserm, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research.

Prof Multigner has investigated the chlordecone crisis and says Antilles residents are very anxious and feel the French state is not doing enough.

"The authorities have banned fishing near the coast, but small-scale fishermen get by from day to day, so they are out of work," he told the BBC.

"One-third of coastal waters are contaminated, all the rivers are - fishing is banned there. Agricultural land is 30-50% contaminated, so some cultivation has to stop."

However, he notes that the chemical does not contaminate bananas.

Last year the official unemployment rate in Guadeloupe was 23% and in Martinique 18%, compared with 9% in mainland France. The Antilles rely heavily on French state subsidies.

Serge Letchimy, a Martinique MP leading the French parliamentary inquiry, said half of the island's 24,000 hectares (59,305 acres) of agricultural land had some chlordecone contamination, and 4,000 ha of that was totally polluted.

Ms Benin said compensation claims would follow the inquiry, but "the priority is more research, we need soil analysis and impact assessments for the affected farmers".

Determining responsibility was proving hard because the pesticide's licensing and distribution was complicated, she said.

"The kepone licence was resold several times," she said, adding that so far the inquiry had been unable to speak to the producers.

What is the health impact?

A study in 2013-2014 found that among adults in Martinique, 95% had chlordecone in their blood, while the figure for Guadeloupe was 93%. That corresponds to about 750,000 people.

In 2010 Prof Multigner and colleagues found a link between higher chlordecone concentrations in the blood and prostate cancer. Their conclusion was based on a study of 623 men in Guadeloupe with newly diagnosed prostate cancer and a control group of 671.

The World Cancer Research Fund reports that prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide.

In 2018, the highest rates in the world were in Guadeloupe (189 per 100,000) and Martinique (158 per 100,000). The rate for mainland France was 99.

"Chlordecone contributes to the higher rate [in the Antilles], but it is not the only factor," Prof Multigner said. Ethnicity and lifestyle are also factors in hormone-dependent cancers.

Prostate cancer is more common among Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American men than among white Europeans or Asians. But testicular cancer rates are higher among white European men.

Inserm's research also found a link between chlordecone exposure and "adverse effects on cognitive and motor skills development in infants".

Another scientific study in the Antilles suggested that the chemical was a factor in premature births.

The chemical is very slow to break down in the environment: contamination can persist for centuries, experts say.

It was restricted globally under the Stockholm Convention in 2016, along with 25 other "Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)".

How big is the problem?

"The economic impact is enormous," says Prof Luc Multigner, head of research at Inserm, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research.

Prof Multigner has investigated the chlordecone crisis and says Antilles residents are very anxious and feel the French state is not doing enough.

"The authorities have banned fishing near the coast, but small-scale fishermen get by from day to day, so they are out of work," he told the BBC.

"One-third of coastal waters are contaminated, all the rivers are - fishing is banned there. Agricultural land is 30-50% contaminated, so some cultivation has to stop."

However, he notes that the chemical does not contaminate bananas.

Last year the official unemployment rate in Guadeloupe was 23% and in Martinique 18%, compared with 9% in mainland France. The Antilles rely heavily on French state subsidies.

Serge Letchimy, a Martinique MP leading the French parliamentary inquiry, said half of the island's 24,000 hectares (59,305 acres) of agricultural land had some chlordecone contamination, and 4,000 ha of that was totally polluted.

Ms Benin said compensation claims would follow the inquiry, but "the priority is more research, we need soil analysis and impact assessments for the affected farmers".

Determining responsibility was proving hard because the pesticide's licensing and distribution was complicated, she said.

"The kepone licence was resold several times," she said, adding that so far the inquiry had been unable to speak to the producers.

What is the health impact?

A study in 2013-2014 found that among adults in Martinique, 95% had chlordecone in their blood, while the figure for Guadeloupe was 93%. That corresponds to about 750,000 people.

In 2010 Prof Multigner and colleagues found a link between higher chlordecone concentrations in the blood and prostate cancer. Their conclusion was based on a study of 623 men in Guadeloupe with newly diagnosed prostate cancer and a control group of 671.

The World Cancer Research Fund reports that prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide.

In 2018, the highest rates in the world were in Guadeloupe (189 per 100,000) and Martinique (158 per 100,000). The rate for mainland France was 99.

"Chlordecone contributes to the higher rate [in the Antilles], but it is not the only factor," Prof Multigner said. Ethnicity and lifestyle are also factors in hormone-dependent cancers.

Prostate cancer is more common among Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American men than among white Europeans or Asians. But testicular cancer rates are higher among white European men.

Inserm's research also found a link between chlordecone exposure and "adverse effects on cognitive and motor skills development in infants".

Another scientific study in the Antilles suggested that the chemical was a factor in premature births.

A Guadeloupe market: There are fears about produce grown on contaminated soil

What is France doing about it?

Since 2008 France has conducted public awareness campaigns in the Antilles, warning of the chlordecone risk.

The islands' authorities are monitoring local fruit and vegetables, as well as meat and fish.

The French ministers of health, overseas territories, research and agriculture have been questioned at the parliamentary inquiry.

But MP Serge Letchimy said just 16% of the polluted land had been mapped and "the measures adopted to deal with this drama bear no relation to its gravity".

What is France doing about it?

Since 2008 France has conducted public awareness campaigns in the Antilles, warning of the chlordecone risk.

The islands' authorities are monitoring local fruit and vegetables, as well as meat and fish.

The French ministers of health, overseas territories, research and agriculture have been questioned at the parliamentary inquiry.

But MP Serge Letchimy said just 16% of the polluted land had been mapped and "the measures adopted to deal with this drama bear no relation to its gravity".

Read more on pesticide risks:

Monsanto 'compiled dossier' on political opponents

Dangerous chemicals found in nappies

New pesticides 'may have risks for bees'

Disrupting chemicals ‘cost billions’

Monsanto 'compiled dossier' on political opponents

Dangerous chemicals found in nappies

New pesticides 'may have risks for bees'

Disrupting chemicals ‘cost billions’

No comments:

Post a Comment