‘It’s a sweat factory’: Instacart workers ready to strike for pay and conditions

Gig workers report falling wages, unmanageable orders and lack of concern from the company

Gloria Oladipo

@gaoladipo

Fri 15 Oct 2021

For Instacart workers across the country, the popular grocery delivery app promised flexibility and a solid wage, perks that enticed thousands to join the app during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

But amid worsening working conditions including plummeting pay, safety concerns, and a punitive rating system, Instacart employees, known as shoppers, will be staging a walkout on 16 October and will continue striking until the company meets their demands for better treatment.

Workers, uniting as the Gig Workers Collective, have been organizing against Instacart for years, citing what they say is a trend of unresponsiveness from the company in the face of their concerns. The collective’s asks are mostly for a restoration of features the company has dropped: reinstating Instacart’s commission pay model, paying its shoppers per order rather than bundling them, a 10% default tip instead of the current 5%, transparency about how orders are assigned, and a rating system that doesn’t hurt shoppers forproblems outside their control.

Shoppers have also asked for occupational death benefits, noting the increasing dangers shoppers face on the job.

Ahead of the walk-off, the Guardian spoke to three Instacart shoppers on their journey to joining Instacart, problems they have encountered since joining the app, and why they’re participating in the 16 October protest.

Willy Solis, 43, Instacart shopper in Texas since October 2019, lead organizer with the Gig Workers Collective

For Willy Solis, Instacart started as a way to make ends meet during a transitional employment period. After running a business since 2008 and while trying to move out of state, he joined Instacart because it offered a low bar of entry and the flexibility Willy needed.

“I thought it was a pretty good deal as far as the pay compared to what I was actually doing, the time frame I was allowed to do it in, and all that stuff,” said Solis.

Advertisement

But soon, Solis noticed dips in his pay – small at first, but ever-growing. When Instacart decided to bundle individual orders together (“batches” as shoppers call them), batches began to double and triple in size – with 60 or 70 items in a batch for multiple orders at different addresses – while the pay remained the same. Tips, which make up the bulk of pay for shoppers, also dropped when Instacart’s default tip was set at a paltry 5%.

In some cases, he was making up to 50% less than average on orders. Soon, Solis was experiencing huge cuts in his pay from when he started. While he once brought home $1,000 a week, now Solis often struggles to break $500 for a week’s work after sitting on the app for hours in search of profitable orders, even while working across multiple apps besides Instacart.

“It’s getting to the point where it’s just not enough and I’m not making what I need to make,” said Solis.

Instacart’s changing pay structure is the source of at least two class-action lawsuits, but safety is also something Solis has struggled with. As an immunocompromised person, trying to stay safe during the pandemic while having to work to pay bills was a challenge that Instacart offered little support with.

While the company did send out personal protective equipment (PPE) to shoppers after facing public outrage and mounting collective action, Solis says the PPE was of poor quality and he was never compensated for the equipment he bought himself. When Solis did get Covid, he didn’t qualify for Instacart’s pay assistance program, and had to rely on family during the two months he was unable to work.

Advertisement

“It was a very tough period of time financially,” said Solis. “I had to work my tail off to try and get back on track.”

Changes to Instacart’s support service, now automated, has also left Solis feeling unsafe on the job. During threatening situations Solis has experienced, having live Instacart support was important for de-escalation; now, he says, that human resource is gone.

Instacart’s newly tenured CEO, Fidji Simo, has offered little response to workers’ concerns, and Solis says he’s ready to strike.

“I’m participating in the Instacart walkout because I feel like there is no other option. We don’t have another choice but to get so loud and so vocal that we bring that kind of attention to the issues,” said Solis.

Jen, shopper advocate, 54, based in Massachusetts, shopping with Instacart since April 2020

During the pandemic, the clothes business side hustle that Jen had established came to sudden halt. Looking for a different income source, Jen noticed long wait times on Instacart’s app while trying to get her own groceries delivered. She was intrigued and decided to sign up for herself. (Jen asked to be identified with her first name only for safety reasons.)

“I thought, ‘Well, let me help during the pandemic. Let me make money and let me also help with this shortage of shoppers.’”

Shopping on Instacart was enjoyable at first; using the app was convenient and demand was still high. But with Instacart’s dropping pay and losing profitable orders with bots, hackers using stolen Instacart shopper accounts to shop on the app, Jen struggled to find competitive orders.

“I haven’t shopped in more than four weeks now because there’s not one batch that comes on my screen that would put me making over minimum wage,” said Jen.

Jen also struggled with Instacart’s rating system, often described as “punishing” by shoppers. While Instacart maintains the system is fair and allows for the lowest rating of 100 deliveries to be dropped, shoppers remarked that a rating slightly below 5 stars could significantly affect their earning potential.

Jen found herself frequently penalized for false accusations of not delivering items from customers. On one occasion, after delivering bulk bags of Halloween candy to one shopper, Jen was penalized for not fulfilling the order – even though she had pictures of the completed delivery and she saw the customer bring the order inside.

Advertisement

“At the end of the day, nothing happened. The customer got the candy for free and I was punished.”

Jen, who runs a YouTube channel about her experiences with Instacart and aggregated concerns she hears from others, noted Instacart’s indifferent response to shoppers’ concerns, including failing to address the impact that customer fraud has on shoppers.

“Instacart doesn’t care. It’s a revolving door. It’s like a sweat factory. They’ll put 100 in, fire 10, and put 100 more back in. They are soulless when it comes to their frontline workers,” she said. “It’s just not OK. We’re human beings and we deserve to be treated like such.”

Robin Pape, 42, based in upstate New York, Instacart shopper since 2018

In 2018, after receiving an Instacart referral link from a friend who needed the extra sign-up bonus, Robin Pape decided to try the app out. But soon, with Instacart’s new pay structure, Pape saw her pay fall by more than a third.

Most of the Pape spends on the app she is waiting for worthwhile delivery orders, as batches grow increasingly scarce given the more than 200% increase in active Instacart workers in Pape’s area since the time she started.

“They were so proud [of] the hundreds of thousands of shoppers they were hiring [during the pandemic] while still not sending out PPE or appropriate hazard pay,” said Pape.

Like other shoppers, Pape has had run-ins with Instacart’s harsh rating system. She has seen her ratings drop even when customers don’t add a rating at all. Pape noted additional challenges: changing store layouts, a national supply shortage and other conditions that remain out of her control.

“There are certainly people who feel like [an Instacart shopper] is not a skilled position. But there certainly are a lot of skills in navigating the stores and shopping for three different customers and communicating with them and keeping it all straight and doing it efficiently enough to be competitive in this gig,” said Pape.

As one of Gig Worker Collective’s founding members, Pape believes the upcoming walkout is an opportunity to speak out against Instacart and treatment that has “only gotten worse and worse and worse”.

“I’m supporting the Instacart walkout because if a company can’t afford to pay their contractors a living wage, they don’t need to be in business,” said Pape.

Instacart shopper activists are going on strike

They want better wages and transparent communication with the company

On Saturday, some Instacart shoppers will go on strike, protesting the company’s low pay and lack of communication with its laborers. The action is led by the Gig Workers Collective, formed in early 2020, though Instacart shoppers have organized several walk-offs since 2016. At the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns in the U.S., for instance, the collective rallied for better safety precautions amid the outbreak.

The Gig Workers Collective — representing a body of about 13,000 of Instacart’s 500,000 shoppers — launched a campaign last month urging customers to delete the Instacart app as a show of solidarity with shoppers’ demands. But Instacart didn’t address the collective’s demands, which include being paid by individual order, not by a batch of orders; to re-introduce item-based commissions; to ensure the rating system doesn’t punish shoppers for issues beyond their control; to provide occupational death benefits; and to make the default tip at least 10%, up from the current 5% default. Now, the shopper activists will go on strike until these demands are met.

Some shoppers are frustrated that despite Instacart’s $39 billion valuation, they feel it’s becoming harder to make a reasonable hourly rate on the platform. In the past, Instacart had a $10 minimum on earnings for each batch a shopper completed (batches can contain between one and three individual customers’ orders). But after founder and former CEO Apoorva Mehta publicly apologized in February 2019 for subsidizing this $10 minimum with shoppers’ tips, the minimum batch pay changed to $7 for full-service shoppers, who both pick the groceries and deliver them. Instacart framed this as “a higher guaranteed floor” — the previous minimum batch payment was $3, though shoppers always got at least $10 because of the established minimum (which was paid for in part with shoppers’ own tips, unbeknownst to them at the time). But with that policy removed, some shoppers are making even less money than they were before the policy change.

Now, a shopper might fill three customers’ individual orders for a minimum total of $7 base pay, before tips. Instacart told TechCrunch that it considers items, mileage, weight and other factors when determining payment for a batch. But Willy Solis, a lead organizer for the Gig Workers Collective and Instacart shopper, told TechCrunch that there’s “no rhyme or reason” to the way orders are combined into batches.

“You would think that they would be in the same geographic location that you’re delivering to, but they’re not,” he said. “It can be totally different parts of the city, so you have to drive east for one and west for the other.”

Instacart told TechCrunch that batching orders makes it possible for shoppers to earn three individual tips off of one trip to the grocery store. But this means that shoppers can only earn decent compensation if their customers tip appropriately. When customers go to check out, the default tip option is 5%. One of the collective’s goals of the strike is to raise the default to 10%, which was standard on the platform in 2016. If a customer tips higher than 5%, that percentage will auto-populate as the default for their next order, but shoppers are still finding that they aren’t making adequate hourly wages.

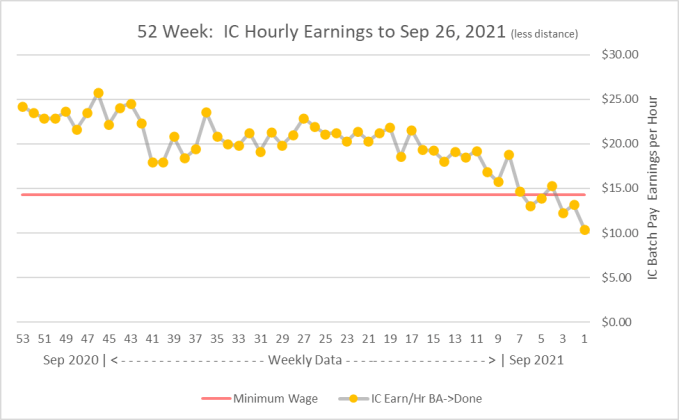

The Gig Workers Collective told TechCrunch that workers have seen a significant slash to their earnings over the last three months. A shopper in Canada, Daniel Feuer, recently wrote an open letter to Instacart CEO Fidji Simo, who took the helm of the company in July. He created a graph that shows his hourly wage over the last year.

“It’s not gone unnoticed that, in the company’s pre-IPO drive to profitability, batch earnings pay has been drastically cut,” he wrote. “See how it starts dropping in May this year?”

Image Credits: Daniel Feuer

Other shoppers have also observed that their pay has gone down over time. Shoppers pay for their own gas, car insurance and car expenses, so their take-home pay stretches less than it might seem.

“My pay has gone down probably 70% since I started four years ago,” said Sharon Goen, a 58-year-old Instacart shopper based in Las Vegas, Nevada. “It used to be that anything over 24 items, you get a bump in pay. Now, it’s $7 a batch. I saw one the other day that had 77 unique items, 100 units, for $7. You can’t go through the store and get 77 items in 15 minutes. You’re there for an hour and a half.”

Anni McClung, a shopper based in Houston, Texas, started shopping on Instacart four months ago. But she’s already confused by how pay is calculated.

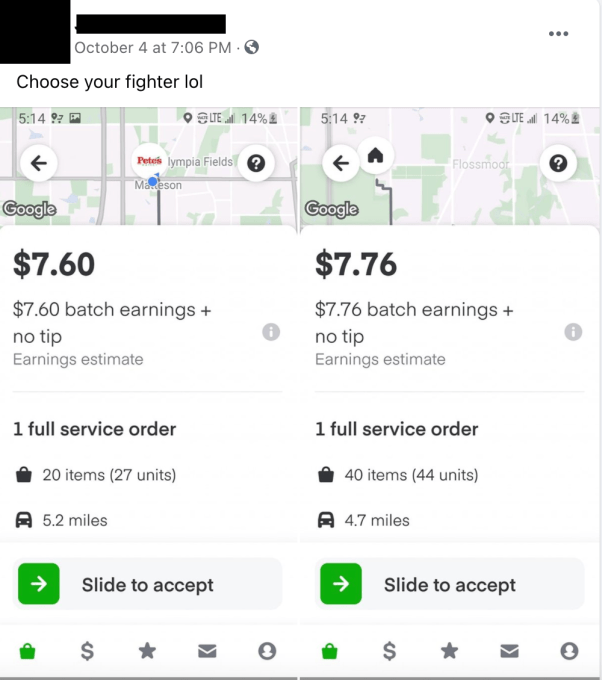

“I would like someone to explain to me why for one batch I get $7, for two batches I get $7 and for three batches I get $7. Seems like they have to pay me $21,” McClung told TechCrunch. “Why is it $7 for half a mile, and also $7 for 6.8 miles?”

McClung, who will participate in the strike, said that she tried to contact Instacart’s customer service line for shoppers to learn how mileage is calculated into base pay for a batch. She said that she was routed to three different representatives without receiving an answer.

TechCrunch asked Instacart to clarify how base pay is impacted by the distance a shopper has to drive. The company said that mileage is incorporated into a shopper’s base pay at a rate of $0.60 per mile from store to customer delivery, except in California, where the rate is $0.30 per mile. But shoppers aren’t seeing that value reflected in their batches. Instacart declined to tell TechCrunch whether or not the $7 minimum is inclusive of the $0.60 per mile driven. If that is the case, then that would explain why shoppers might see a batch that’s five miles away for less than $8 — if the mileage were added to the minimum labor fee, then a five-mile drive would give the shopper an extra $3 to their $7 base.

Image Credits: Screenshot from Instacart Chicago Shoppers group on Facebook, obtained by TechCrunch

Instacart contracted 300,000 more shoppers during the coronavirus pandemic since the demand for grocery delivery was higher than ever. Instacart told TechCrunch that its shopper population has remained steady at around 500,000 shoppers since then, and that customer demand is four times higher than it was at the start of 2020. Since March 2020, Instacart said shoppers have earned more than $5.5 billion on the platform.

But as customers adapt to the conditions of the pandemic, shoppers observe that fewer customers are using the service, making it harder to get work on the app. Instacart said that there are waitlists to become a shopper in many regions. Shoppers that spoke to TechCrunch from Nevada, Texas and New York all reported that their markets are oversaturated with shoppers’ demand for batches to fill.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, it was great. I was making anywhere from $1,200 to $1,500 a week only working about 30 hours or so,” said JoJo Spatafora, a shopper in Staten Island, New York who has been with Instacart for three years. “But it seems as if things have changed and they over-hired. Instacart has been aware of this and has not done anything about it. They only care about customers, not their shoppers.”

In the past, shoppers would set the hours they wanted to work, and during that time, they would be individually assigned batches — they had four minutes to look it over and decide if they wanted to accept before it would be assigned to someone else. Since 2019, Instacart has used an on-demand system, where shoppers can choose to work at a moment’s notice. Because of that, many shoppers will be offered a batch at once, which shows the base pay, tip, distance to drive, and a preview of the items in the order — whoever swipes on the batch first gets the job. Goen told TechCrunch that her area is so oversaturated with shoppers that when a batch pops up, she needs to accept it without taking much time to look over the details.

“I’m 58 years old, and if I see something that’s got a decent pay, I don’t have the time to see how many cases of water are going to a third-floor apartment,” Goen said. “I just can’t physically do those kinds of orders anymore, and if I were to accept that and then cancel it, that would go against my acceptance rate.” If a shopper has canceled around 15% of their last 100 orders, they will start to receive notices from Instacart before their account is suspended.

Shoppers going on strike hope that this action will get the attention of CEO Fidji Simo. Instacart told TechCrunch that Simo has been regularly conversing with shoppers about their experiences on the job, but Simo hasn’t responded to the Gig Workers Collective’s open letters.

“As far as the strike, I don’t participate in such nonsense because it does not make a difference,” Spatafora told TechCrunch. “Once when shoppers went on strike, Instacart decided to punish us by removing the three-dollar bonus every time a customer gives us a five-star rating.”

Spatafora is referring to a past Instacart policy that would give shoppers an extra $3 for each order they completed with a five-star rating. Workers were tipped off that the bonus would last through January 2020. But when shoppers went on strike in November 2019 to demand that the default tip be raised from 5% back to 10%, the company removed the bonus soon after. Instacart said that it always planned to end the bonus in November 2019, but the Gig Workers Collective claimed that this was an act of retaliation.

“Are we really going to impact business? Probably not,” said Goen. Instacart affirmed to TechCrunch that they don’t expect to see a change in their revenue. “But this will be my sixth walk-off I think. I’m going to keep doing it ’til we make progress. And we have made progress every now and then.”

No comments:

Post a Comment