The Belgian Idealist sought to depict the elevation of the human spirit in his art, believing that the defiance of base desires could lead to spiritual enlightenment

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Jul 23, 2021

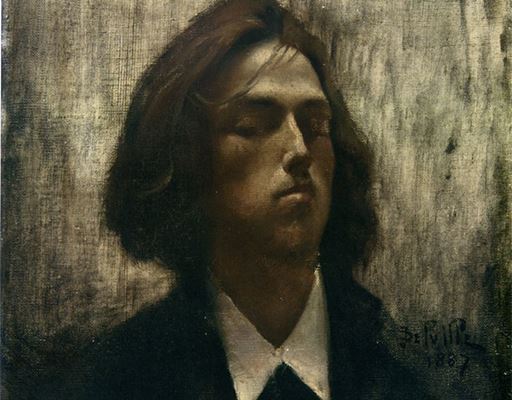

Jean Delville, Self Portrait, 1887, Unknown Collection

Viewers of art often derive their own interpretations and meanings from the pieces that hang before them. At times, speculations on what the artist was trying to say, are exactly that — speculation — and bear no reflection on what the creator’s actual artistic intentions or motivations were for picking up the paintbrush. It is a common practice, which at times is not unlike staring at a page of text written in a foreign language and exacting an arbitrary translation, then telling those around oneself that the translation is indeed accurate. The truth is that there are some painters who simply paint what they feel, and any profoundly detailed interpretation is, by nature, inaccurate. Then, in contrast, there are other painters that have something very specific to express through their brushstrokes, whether the viewer realizes it or not. This is exemplified in pieces created from the core beliefs of the artist. And if one knows what those core beliefs are, interpretation becomes both easier and more accurate. One of those artists whose paintings are easier to interpret when delving into the spirituality of their creator, is Belgium-born symbolist painter, poet, Theosophist, and occultist, Jean Delville.

Jean Delville led the Belgian idealist movement in the 1890s and believed that art should be representative of a higher spiritual truth, expressed through the ideal, through a beauty indicative of belief. And while Delville discussed his spiritual beliefs frequently and openly, he was rather reticent when it came to discussing his paintings, preferring for the viewer themselves to form their own interpretation. Somewhat ironically, the clues needed to interpret their painter’s motivations, and subsequently the painting’s ‘true’ meaning, are hidden in plain sight.

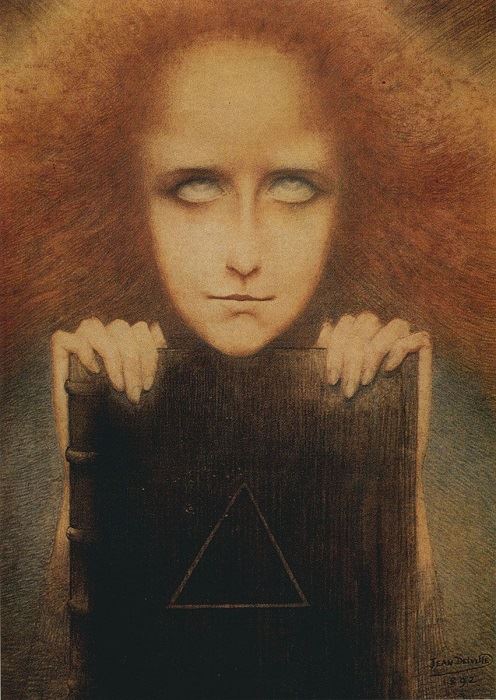

Mysteriosa or The Portrait of Mrs. Stuart Merrill, 1892, pencil, pastel and coloured pencil on paper, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Perhaps Jean Delville’s most well-known painting, Mysteriosa or The Portrait of Mrs. Stuart Merrill is a simplistically composed, albeit fascinating piece. A young, fiery-headed medium clutches a leatherbound black book, its cover inscribed with only a simple triangle, her eyes tilted up as if they are about to disappear completely into the back of her head in a trance-like state. The triangle is representative of Delville’s belief in the idea of ‘perfect human knowledge’ attained through occult practices, and the technique used in making the subject’s hair seem to radiate and bleed into the space around her shows that Mrs. Merrill is indeed transcending into a plane that is not that of the still-breathing mortal. The slender hands that clutch the book are pale and almost spectral, hinting at the divine power hidden within its pages. While little is known of Mrs. Stuart Merrill herself, her husband was a Symbolist poet who had works published in Paris and Brussels. The painting’s air of mystery had led it to be sometimes referred to as the ‘Mona Lisa of the 1890s.’

In the early stages of his artistic career, Delville was influenced by the writings and teachings of such renowned esotericists and occultists as Éliphas Lévi and Saint-Yves d'Alveydre, and later by Theosophists such as Helena Blavatsky and Annie Besant. Great emphasis on the theme of the transfiguration of the soul toward a higher purpose is evident throughout his work. Delville believed that the true purpose of man was to seek spiritual enlightenment, and that the base desires, such as sexual pleasure, the attainment of power, and the accumulation of wealth, all kept mankind from achieving that enlightenment. This ideology is evident in his 1895 painting, Sathan’s Treasures (Les Trésors de Sathan).

Jean Delville

Belgian, 1867 - 1953

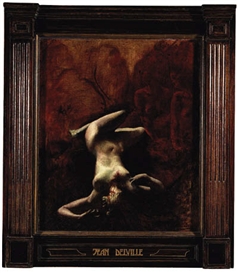

Sathan’s Treasures (Les Trésors de Sathan), 1895, oil on canvas, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

At first glance, Sathan’s Treasures appears to be simply a fantasy piece. A devil or demon cavorts above a stream of nude figures, against the backdrop of a mystical undersea land. And even though that may in fact be what the piece depicts, there is more to the painting than meets the eye. The unclothed figures represent the base nature of mankind, those carnal desires we all possess, and which subsequently come under the jurisdiction of Satan. The Great Deceiver has lured these souls away from the path of enlightenment, and into his underwater lair. Here, they are his ‘treasure,’ hence the painting’s title. Delville expressed his belief in these sentiments in an 1893 article, published in the journal Le Mouvement Littéraire:

“Erotic fever has sterilized most minds. One ordinarily thinks of himself as virile because he satisfies a woman’s unquenched bestial desires. Well, that’s where the great shame of the cerebral degeneration of our time starts…”

L’Homme-Dieu (Man-God), 1903, oil on canvas, Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Composed strikingly in a palette of pastel colors, Delville’s L’Homme-Dieu simply depicts the process of apotheosis. In the painting’s lowest third, its subjects are preoccupied with the animalistic aspects of existence, in the throes of copulation, pain, childbirth, and the like. This morphs into the second third of the painting, the subjects here raising their hands to the heavens, seeking wisdom and enlightenment to be imparted upon them. And once it has, and they have truly understood the spiritual truth of the universe, they can then transcend into a god-like being themselves, all-knowing from where they stand on the highest point of the spiritual ladder. This makes up the uppermost part of the painting. L’Homme-Dieu was painted when Delville’s interest in Theosophy increased, the religion’s followers believing that men, through a process of spiritual enlightenment, can become spiritual masters, similar to the beliefs of the Buddhists.

Jean Delville died in Brussels, Belgium, on January 19, 1953, at the age of 86. And even though he was a driving force in the Belgian idealist movement, he never quite achieved the same fame as his contemporaries. A large part of this was simply due to the fact that he wasn’t interested in doing so. While many Belgian Idealist artists exhibited their work within the highly commercialized exhibition societies, Delville never did so — simply because of his beliefs. Materialistic and monetary gain were not conducive while slowly and steadily travelling up the path of enlightenment. In fact, they were quite the opposite. He believed that art should be used as tool in which to educate society, a beauty created for posterity. He once summed up the sentiment perfectly in his writings:

“There will be nothing to prevent art increasingly to become an educative force in society, conscious of its mission. It is time to penetrate society with art, with the ideal and with beauty. Today's society tends to fall increasingly into instinct. It is saturated with materialism, sensualism and ... commercialism.”

Which unfortunately sounds like it could be referring to a time similar to that in which we currently live in, and most-likely always will.

Belgian, 1867 - 1953

Sathan’s Treasures (Les Trésors de Sathan), 1895, oil on canvas, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

At first glance, Sathan’s Treasures appears to be simply a fantasy piece. A devil or demon cavorts above a stream of nude figures, against the backdrop of a mystical undersea land. And even though that may in fact be what the piece depicts, there is more to the painting than meets the eye. The unclothed figures represent the base nature of mankind, those carnal desires we all possess, and which subsequently come under the jurisdiction of Satan. The Great Deceiver has lured these souls away from the path of enlightenment, and into his underwater lair. Here, they are his ‘treasure,’ hence the painting’s title. Delville expressed his belief in these sentiments in an 1893 article, published in the journal Le Mouvement Littéraire:

“Erotic fever has sterilized most minds. One ordinarily thinks of himself as virile because he satisfies a woman’s unquenched bestial desires. Well, that’s where the great shame of the cerebral degeneration of our time starts…”

L’Homme-Dieu (Man-God), 1903, oil on canvas, Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Composed strikingly in a palette of pastel colors, Delville’s L’Homme-Dieu simply depicts the process of apotheosis. In the painting’s lowest third, its subjects are preoccupied with the animalistic aspects of existence, in the throes of copulation, pain, childbirth, and the like. This morphs into the second third of the painting, the subjects here raising their hands to the heavens, seeking wisdom and enlightenment to be imparted upon them. And once it has, and they have truly understood the spiritual truth of the universe, they can then transcend into a god-like being themselves, all-knowing from where they stand on the highest point of the spiritual ladder. This makes up the uppermost part of the painting. L’Homme-Dieu was painted when Delville’s interest in Theosophy increased, the religion’s followers believing that men, through a process of spiritual enlightenment, can become spiritual masters, similar to the beliefs of the Buddhists.

Jean Delville died in Brussels, Belgium, on January 19, 1953, at the age of 86. And even though he was a driving force in the Belgian idealist movement, he never quite achieved the same fame as his contemporaries. A large part of this was simply due to the fact that he wasn’t interested in doing so. While many Belgian Idealist artists exhibited their work within the highly commercialized exhibition societies, Delville never did so — simply because of his beliefs. Materialistic and monetary gain were not conducive while slowly and steadily travelling up the path of enlightenment. In fact, they were quite the opposite. He believed that art should be used as tool in which to educate society, a beauty created for posterity. He once summed up the sentiment perfectly in his writings:

“There will be nothing to prevent art increasingly to become an educative force in society, conscious of its mission. It is time to penetrate society with art, with the ideal and with beauty. Today's society tends to fall increasingly into instinct. It is saturated with materialism, sensualism and ... commercialism.”

Which unfortunately sounds like it could be referring to a time similar to that in which we currently live in, and most-likely always will.

No comments:

Post a Comment