Student says National University of Singapore censored his graduation death penalty protest

Luke Levy reportedly faces a police probe over the protest, whilst the National University of Singapore says graduations are “not a forum for advocacy.”

Luke Levy reportedly faces a police probe over the protest, whilst the National University of Singapore says graduations are “not a forum for advocacy.”

by TOM GRUNDY08:00,

26 JULY 2022

The National University of Singapore (NUS) stands accused of editing a death penalty protest placard from a student’s graduation photo and livestream. The school told HKFP that the event was “not a forum for advocacy.”

The National University of Singapore (NUS) stands accused of editing a death penalty protest placard from a student’s graduation photo and livestream. The school told HKFP that the event was “not a forum for advocacy.”

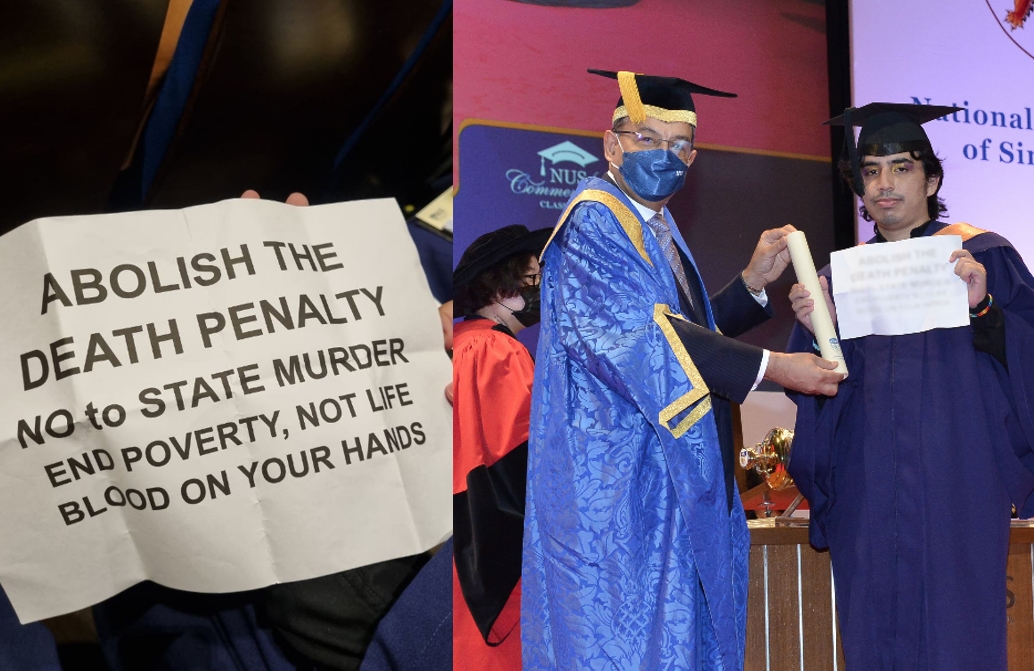

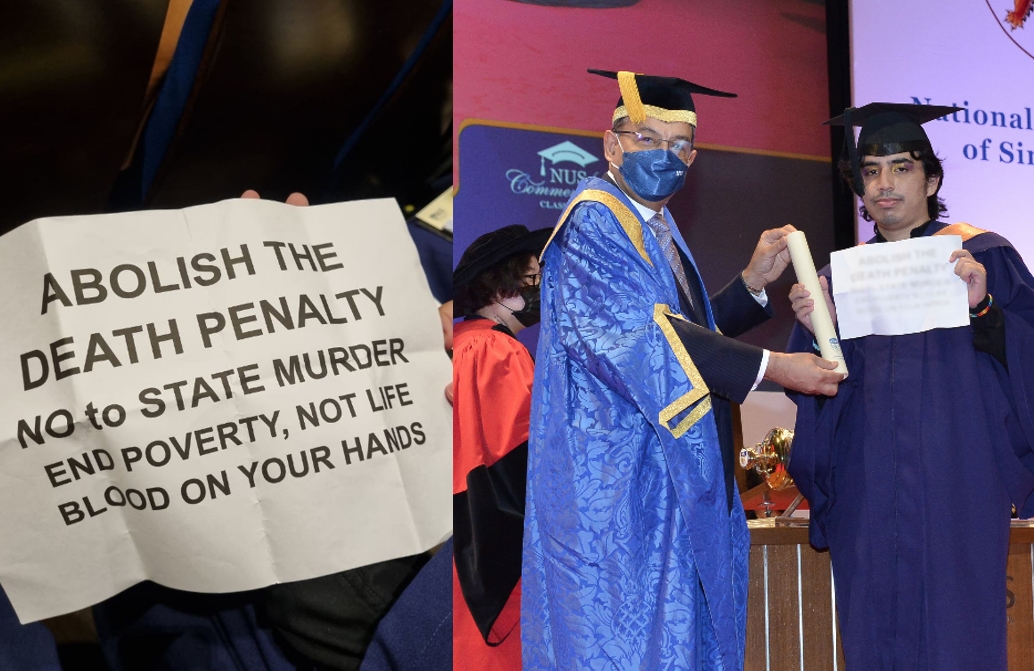

Luke Levy’s protest at the NUS. Photo: AngMohSnowball, via Twitter.

During his graduation ceremony earlier this month, Luke Levy, held up a sign saying “Abolish the death penalty. No to state murder. End poverty, not life. Blood on your hands.”

“I held that sign as I walked on stage, took my on-stage photo, and left the stage, sign in hand… NUS took down the live recording of my commencement ceremony, only to reupload it later with an edit,” Levy said in a tweet.

“In the official stage photograph (that I paid for, for my own private display), the photo studio actually took time to try and edit the words on my sign out,” the 25-year-old activist added.

It comes as Singapore executed its fifth prisoner since March, following a Covid-related pause. In April, the authorities killed a mentally impaired man, as last-ditch appeals for clemency were rejected by the court. The spate of hangings has prompted a fresh wave of criticism and protests.

Levy added that the death penalty “unjustly kills the poor. It is not an effective deterrent of ‘crime’. And there’s no acquittal for those found innocent after execution.”

In response to HKFP’s enquiries, a university spokesperson told HKFP: “The NUS Commencement is an important ceremony celebrating the achievements of our 13,975 graduates and the completion of their NUS journey. All graduates and guests are expected to conduct themselves appropriately during the occasion. It is not a forum for advocacy.”Gardens by the Bay in Singapore. Photo: James Faulkner, via Flickr.

According to Today Online, police are looking into the protest. It cited lawyers as saying the activist may be liable under the Public Order Act, which restricts even single-person protests in public.

During his graduation ceremony earlier this month, Luke Levy, held up a sign saying “Abolish the death penalty. No to state murder. End poverty, not life. Blood on your hands.”

“I held that sign as I walked on stage, took my on-stage photo, and left the stage, sign in hand… NUS took down the live recording of my commencement ceremony, only to reupload it later with an edit,” Levy said in a tweet.

“In the official stage photograph (that I paid for, for my own private display), the photo studio actually took time to try and edit the words on my sign out,” the 25-year-old activist added.

It comes as Singapore executed its fifth prisoner since March, following a Covid-related pause. In April, the authorities killed a mentally impaired man, as last-ditch appeals for clemency were rejected by the court. The spate of hangings has prompted a fresh wave of criticism and protests.

Levy added that the death penalty “unjustly kills the poor. It is not an effective deterrent of ‘crime’. And there’s no acquittal for those found innocent after execution.”

In response to HKFP’s enquiries, a university spokesperson told HKFP: “The NUS Commencement is an important ceremony celebrating the achievements of our 13,975 graduates and the completion of their NUS journey. All graduates and guests are expected to conduct themselves appropriately during the occasion. It is not a forum for advocacy.”Gardens by the Bay in Singapore. Photo: James Faulkner, via Flickr.

According to Today Online, police are looking into the protest. It cited lawyers as saying the activist may be liable under the Public Order Act, which restricts even single-person protests in public.

Singapore wants to kill, but it doesn’t want anyone talking about it

“As a system, capital punishment makes us forget our humanity, but the growing mobilisation of the abolitionist movement in Singapore reminds us that there are many people who care and feel deeply about this issue…” writes anti-death penalty activist Kirsten Han.

by KIRSTEN HAN

21 JULY 2022

2022 is shaping up to be a brutal year in Singapore as the authorities ramp up the speed of executions. Four men have already been hanged this year for drug offences — if not for last-ditch court applications that resulted in stays of execution or respite orders issued by the President, the state would have hanged another four more. Barring a miracle, Nazeri bin Lajim will be hanged in the early hours of Friday morning. Demands for the abolition of the death penalty are more urgent than ever, even as the state clamps down on such dissent.

2022 is shaping up to be a brutal year in Singapore as the authorities ramp up the speed of executions. Four men have already been hanged this year for drug offences — if not for last-ditch court applications that resulted in stays of execution or respite orders issued by the President, the state would have hanged another four more. Barring a miracle, Nazeri bin Lajim will be hanged in the early hours of Friday morning. Demands for the abolition of the death penalty are more urgent than ever, even as the state clamps down on such dissent.

Nazeri bin Lajim with his then-wife, who has continued to visit him in prison.

Singapore retains capital punishment for a range of offences, but uses it most commonly in the context of drug trafficking. Under the Misuse of Drugs Act, a person can be hanged if found guilty of trafficking above a certain threshold of controlled drugs — such as 15g of heroin or 500g of cannabis. The majority of the 495 people hanged in the city-state since 1991 were convicted of drug offences.

Singapore retains capital punishment for a range of offences, but uses it most commonly in the context of drug trafficking. Under the Misuse of Drugs Act, a person can be hanged if found guilty of trafficking above a certain threshold of controlled drugs — such as 15g of heroin or 500g of cannabis. The majority of the 495 people hanged in the city-state since 1991 were convicted of drug offences.

There are currently about 60 people on death row — a significant number for such a small country. Prisoners tell their families that death row is “too full”. They suspect that the prison will schedule as many executions as it can so as to make room for new condemned inmates. They see their lives treated as an administrative problem, and live in fear of the day execution notices will be delivered to their loved ones.

Changi Prison. Photo: Singapore Gov’t.

The situation is desperate. As abolitionist activists working with the family members of people sentenced to death, we see this desperation up close. Every execution notice is felt acutely by every family, even if it isn’t addressed to them. “Every one of them [prisoner on death row] is my brother,” Sonia, older sister of Kalwant Singh, told me in June. Her brother was hanged on 7 July. The prison issued an execution notice to Nazeri bin Lajim’s family just a week later. Sonia hadn’t even completed the last rites for Kalwant before she was texting me about how much it hurt to know that another sister would soon experience the pain she’d felt when she lost her brother. There isn’t enough time to process and grieve one execution before another comes, leaving families in a constant state of anxiety and trauma

The situation is desperate. As abolitionist activists working with the family members of people sentenced to death, we see this desperation up close. Every execution notice is felt acutely by every family, even if it isn’t addressed to them. “Every one of them [prisoner on death row] is my brother,” Sonia, older sister of Kalwant Singh, told me in June. Her brother was hanged on 7 July. The prison issued an execution notice to Nazeri bin Lajim’s family just a week later. Sonia hadn’t even completed the last rites for Kalwant before she was texting me about how much it hurt to know that another sister would soon experience the pain she’d felt when she lost her brother. There isn’t enough time to process and grieve one execution before another comes, leaving families in a constant state of anxiety and trauma

.

Singapore. File photo: Tom Grundy/HKFP.

The Singapore government stubbornly defends its pro-death penalty position. It insists that capital punishment is necessary to deter the drug trade and protect people, even though there’s no clear evidence that proves that the death penalty deters drug offences. But while it claims confidence in this stance, it also takes steps to suppress alternative perspectives and resistance, so that it never has to engage with them.

Information about Singapore’s use of the death penalty is hard to come by. Before this year, the death row population was not publicly known; it took volunteers of the Transformative Justice Collective (of which I’m a member) tracking trials and court judgements to arrive at a number, which the law and home affairs minister recently confirmed in an interview with the BBC. The mainstream media reports on the death penalty when a government body or state organ issues a statement, otherwise it pretends the issue doesn’t exist. They often don’t even report when an execution has taken place.

The Singapore government stubbornly defends its pro-death penalty position. It insists that capital punishment is necessary to deter the drug trade and protect people, even though there’s no clear evidence that proves that the death penalty deters drug offences. But while it claims confidence in this stance, it also takes steps to suppress alternative perspectives and resistance, so that it never has to engage with them.

Information about Singapore’s use of the death penalty is hard to come by. Before this year, the death row population was not publicly known; it took volunteers of the Transformative Justice Collective (of which I’m a member) tracking trials and court judgements to arrive at a number, which the law and home affairs minister recently confirmed in an interview with the BBC. The mainstream media reports on the death penalty when a government body or state organ issues a statement, otherwise it pretends the issue doesn’t exist. They often don’t even report when an execution has taken place.

Singapore’s Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam. Photo: Wikicommons.

In this climate, capital punishment is not an issue for which any political party is willing to stick their necks out on. Although the families of Singaporean death row prisoners have collected hundreds of signatures for a parliamentary petition calling for a moratorium on executions, they haven’t been able to find a Member of Parliament — whether from the ruling party or the opposition — to carry it into the House on their behalf.

Abolitionist lawyers have also felt the heat. Filing a late-stage application (i.e. after the standard trial and appeal process is over) carries the risk of being accused of abusing court process, and subject to hefty cost orders, paid for by the lawyers themselves. M Ravi, a human rights lawyer who has fought the death penalty in the courts for 20 years, has been ordered to pay tens of thousands of Singaporean dollars in cost orders to the Attorney-General’s Chambers. The climate is such that multiple death row prisoners seeking legal representation for late-stage applications have found it impossible to find a lawyer willing to take on the challenge.

The task then falls to activists to push the issue onto the national stage as best we can, but avenues are limited. There is only one park in the whole country where demonstrations can be held without prior permission. In April, two anti-death penalty protests drew crowds of about 400 people each — significant for a protest-averse country like Singapore — but more widespread action is needed, and that comes at a cost. A number of activists, including myself, are currently under police investigation for illegal assembly in relation to small-scale, non-violent actions related to the death penalty. A graduate from the National University of Singapore has been summoned for police questioning because he held up an anti-death penalty sign while accepting his degree onstage.

Fighting the death penalty in an authoritarian state has always been an uphill battle, and this year looks especially grim as the relentless pace of executions breaks us down and wears us out. Yet there are still reasons to be hopeful: there’s also been an unprecedented momentum for abolition over the past year, with Singaporeans from different walks of life calling for an end to the killing. Families of death row prisoners have also grown more united, coming together in solidarity to talk about their shared experiences and to campaign in support of one another. As a system, capital punishment makes us forget our humanity, but the growing mobilisation of the abolitionist movement in Singapore reminds us that there are many people who care and feel deeply about this issue, and want to be there for the families going through the hardest times. Such reminders are more necessary than ever — it is only by standing together that we can withstand the onslaught and work towards a Singapore without such state violence.

In this climate, capital punishment is not an issue for which any political party is willing to stick their necks out on. Although the families of Singaporean death row prisoners have collected hundreds of signatures for a parliamentary petition calling for a moratorium on executions, they haven’t been able to find a Member of Parliament — whether from the ruling party or the opposition — to carry it into the House on their behalf.

Abolitionist lawyers have also felt the heat. Filing a late-stage application (i.e. after the standard trial and appeal process is over) carries the risk of being accused of abusing court process, and subject to hefty cost orders, paid for by the lawyers themselves. M Ravi, a human rights lawyer who has fought the death penalty in the courts for 20 years, has been ordered to pay tens of thousands of Singaporean dollars in cost orders to the Attorney-General’s Chambers. The climate is such that multiple death row prisoners seeking legal representation for late-stage applications have found it impossible to find a lawyer willing to take on the challenge.

The task then falls to activists to push the issue onto the national stage as best we can, but avenues are limited. There is only one park in the whole country where demonstrations can be held without prior permission. In April, two anti-death penalty protests drew crowds of about 400 people each — significant for a protest-averse country like Singapore — but more widespread action is needed, and that comes at a cost. A number of activists, including myself, are currently under police investigation for illegal assembly in relation to small-scale, non-violent actions related to the death penalty. A graduate from the National University of Singapore has been summoned for police questioning because he held up an anti-death penalty sign while accepting his degree onstage.

Fighting the death penalty in an authoritarian state has always been an uphill battle, and this year looks especially grim as the relentless pace of executions breaks us down and wears us out. Yet there are still reasons to be hopeful: there’s also been an unprecedented momentum for abolition over the past year, with Singaporeans from different walks of life calling for an end to the killing. Families of death row prisoners have also grown more united, coming together in solidarity to talk about their shared experiences and to campaign in support of one another. As a system, capital punishment makes us forget our humanity, but the growing mobilisation of the abolitionist movement in Singapore reminds us that there are many people who care and feel deeply about this issue, and want to be there for the families going through the hardest times. Such reminders are more necessary than ever — it is only by standing together that we can withstand the onslaught and work towards a Singapore without such state violence.

KIRSTEN HAN is a Singaporean freelance journalist and Editor-in-Chief of New Naratif, a platform for Southeast Asian journalism, research, art and community-building. Her bylines have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian and Asia Times, among others. She also curates We, The Citizens, a weekly newsletter on Singaporean current affairs.More by Kirsten Han

No comments:

Post a Comment