Jennifer Rankin in Brussels

Sun, 28 July 2024

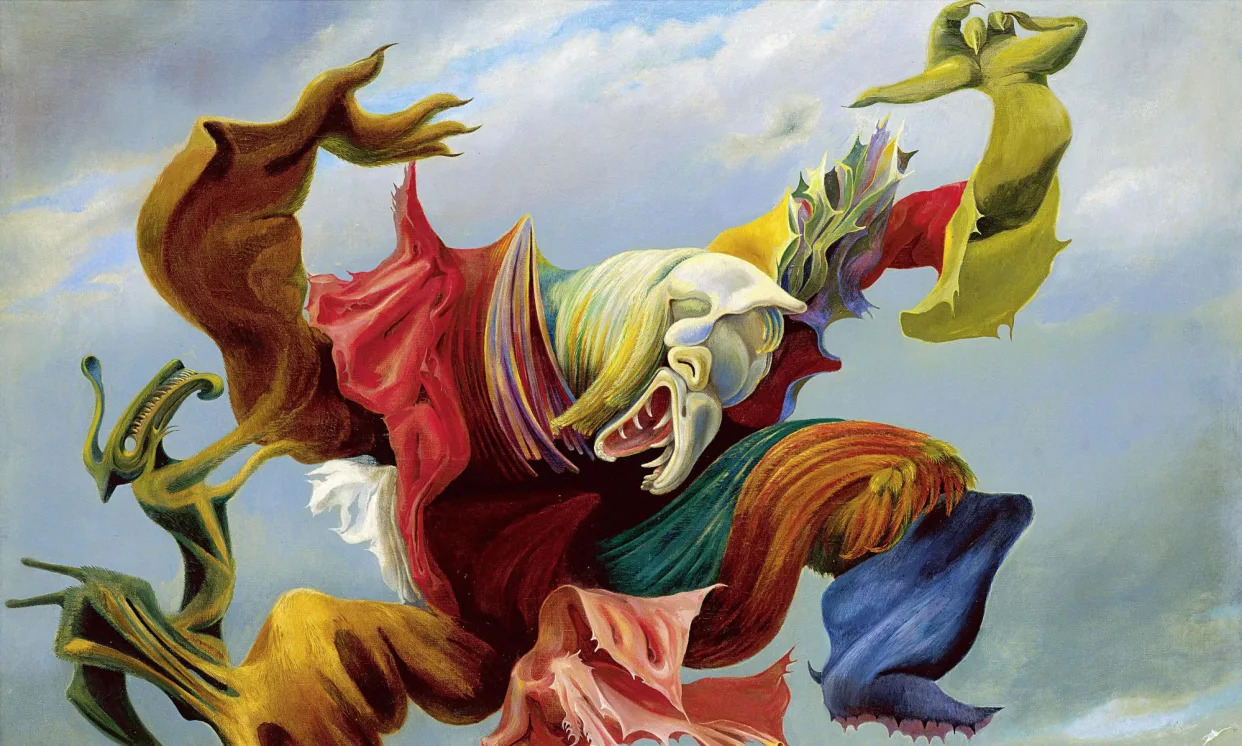

Max Ernst: The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism)

.Photograph: Classicpaintings/Centre Pompidou

One hundred years ago, in a tiny studio flat in a bohemian district of Paris, a former medical student turned writer set out to define surrealism “for once and for all”. In his Manifesto of Surrealism André Breton called for a new kind of art and literature fired by the unconscious, “the dictation of thought free from any control by reason, exempt from aesthetic or moral preoccupation”.

Far from settling surrealism “for once and for all”, the handwritten document was a departure point for a sprawling, subversive movement of bad dreams, haunting landscapes, fantastical alien creatures, unsettling portraits and visual tricks. Now, a century later, a major exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, opening in September, will celebrate how surrealism spread around the world, far beyond the environs of the French capital.

The Paris exhibition is the second in a sequence of five. The show opened in Brussels and will move on to Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia in 2025. Organisers say it is an unprecedented way to organise an exhibition: while some works and themes remain constant in each city, others change and each museum tells its own story.

Perfect, then, for a movement that always aimed to subvert traditional artistic norms.

When the Pompidou Centre last held a major exhibition on surrealism in 2002, it was characterised as an essentially European movement emanating from a group in Paris. Since then, a great deal of research by universities and museums has enlarged that view, said Marie Sarré, the curator of the show at the Pompidou Centre, the organisation that initiated the project. “This exhibition, on the centenary, aims to show surrealism in all its diversity,” she said.

“It is important to remember that surrealism was a movement that spread – and this is exceptional for an avant-garde movement – around the world, in Europe, but also the United States, South America, Asia and the Maghreb.”

What unites all these artists is Breton’s call to live by the imagination, she suggests. “There is this attention to the wondrous in everyday life. [Surrealism] wants to provoke, to shock, [to show] the wonderful aspect of everyday life that comes from consciousness or access to dreams.”

At the heart of the exhibition will be Breton’s first manifesto, with pages of the original manuscript on display, in a loan from the French national library, which acquired the document in 2021 after it was declared a national treasure.

The emblematic names of the surrealist movement will be present, with works by René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. But visitors will find less well-known figures, such as Japanese artist Tatsuo Ikeda, whose art evoked the horrors of war and the toxic consequences of Japan’s postwar reindustrialisation, and Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican painter active in the middle of the 20th century, who is credited with fusing modernism with pre-Columbian motifs in vividly coloured works.

Reflecting a growing tendency, the Pompidou Centre restores to view neglected female artists, who were long reduced to girlfriends and muses with colourful bit parts in the surrealist story, rather than complex creatives in their own right, such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothy Tanning and Dora Maar.

And it will show surrealism’s contemporary resonances, suggests Marré, citing the surrealist preoccupation with the forest as an echo of modern environmentalism. Surrealism’s anticolonial messages also feature – the Paris exhibition includes artists’ tracts against France’s 1954-62 war in Algeria.

In Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts took the concept of surrealism backwards in time, looking at the links between late 19th-century symbolists and the surrealists, long seen as separate movements.

“There was no real rupture between what happened before and after the first world war,” said Francisca Vandepitte, the curator of the Brussels exhibition, which closed in late July. “Our fundamental approach is trying to show, for the first time, the links,” she said, citing Fernand Khnopff’s austere, somewhat unsettling late 19th-century portrait of his sister as an influence on Magritte’s 1932 work The Unexpected Answer, which shows a person-sized hole in a similarly sterile-looking doorway.

Related: Keeping it surreal: my Dalí-inspired art trip to Catalonia

Many of the works that were on display in Brussels are going to Paris, although the show will continue to evolve as it tours. The Royal Museum of Fine Arts is lending one of the jewels of its collection to Paris: René Magritte’s The Dominion of Light, where a clear blue sky filled with white fluffy clouds frames a row of trees and houses shrouded in nocturnal light. “If only the sun could shine tonight,” went a 1923 Breton poem that Magritte quoted.

But “it is not the classic travelling exhibition”, said Vandepitte. Instead, similar themes will emerge in some, but not of all the museums, themes suggested by Breton’s manifesto: dreams and nightmares, night, forests, the cosmos. “Each partner puts on the exhibition, building on the richness of its own collections and heritage,” she said.

After Paris, the exhibition moves to the Fundacíon Mapfre in Madrid, which will turn the spotlight on surrealists from the Iberian peninsula, such as Dalí and Joan Miró. Then it is on to the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which will explore the heritage of German romanticism, before arriving at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in late 2025 to tell the story of surrealists in the Americas during their second world war exile.

Fleeing the Nazi advance, artists came to the US, Mexico and the Caribbean, where they encountered new influences. In Mexico, for instance, surrealists discovered traditional mythologies about volcanoes, “wonderful fodder for the surrealist mindset”, says Matthew Affron, the curator of the Philadelphia exhibition.

“Someone who sees all five versions [of the exhibition] is going to have a wonderfully varied and broad understanding both of the character of surrealist art, in terms of its themes and styles, [and] its main concerns,” he said.

Perhaps the changing nature of the exhibition is particularly well suited to surrealism in all its strange and transgressive variety. “There is no such thing as surrealist style,” Affron said. “I would say it’s really a philosophy of life, almost, and a mindset. One of the key ideas of surrealism is that we must let the imagination be freed to take us to places that we have not yet been.”

Surrealism is at the Pompidou Centre in Paris from 4 September to 13 January

One hundred years ago, in a tiny studio flat in a bohemian district of Paris, a former medical student turned writer set out to define surrealism “for once and for all”. In his Manifesto of Surrealism André Breton called for a new kind of art and literature fired by the unconscious, “the dictation of thought free from any control by reason, exempt from aesthetic or moral preoccupation”.

Far from settling surrealism “for once and for all”, the handwritten document was a departure point for a sprawling, subversive movement of bad dreams, haunting landscapes, fantastical alien creatures, unsettling portraits and visual tricks. Now, a century later, a major exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, opening in September, will celebrate how surrealism spread around the world, far beyond the environs of the French capital.

The Paris exhibition is the second in a sequence of five. The show opened in Brussels and will move on to Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia in 2025. Organisers say it is an unprecedented way to organise an exhibition: while some works and themes remain constant in each city, others change and each museum tells its own story.

Perfect, then, for a movement that always aimed to subvert traditional artistic norms.

When the Pompidou Centre last held a major exhibition on surrealism in 2002, it was characterised as an essentially European movement emanating from a group in Paris. Since then, a great deal of research by universities and museums has enlarged that view, said Marie Sarré, the curator of the show at the Pompidou Centre, the organisation that initiated the project. “This exhibition, on the centenary, aims to show surrealism in all its diversity,” she said.

“It is important to remember that surrealism was a movement that spread – and this is exceptional for an avant-garde movement – around the world, in Europe, but also the United States, South America, Asia and the Maghreb.”

What unites all these artists is Breton’s call to live by the imagination, she suggests. “There is this attention to the wondrous in everyday life. [Surrealism] wants to provoke, to shock, [to show] the wonderful aspect of everyday life that comes from consciousness or access to dreams.”

At the heart of the exhibition will be Breton’s first manifesto, with pages of the original manuscript on display, in a loan from the French national library, which acquired the document in 2021 after it was declared a national treasure.

The emblematic names of the surrealist movement will be present, with works by René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. But visitors will find less well-known figures, such as Japanese artist Tatsuo Ikeda, whose art evoked the horrors of war and the toxic consequences of Japan’s postwar reindustrialisation, and Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican painter active in the middle of the 20th century, who is credited with fusing modernism with pre-Columbian motifs in vividly coloured works.

Reflecting a growing tendency, the Pompidou Centre restores to view neglected female artists, who were long reduced to girlfriends and muses with colourful bit parts in the surrealist story, rather than complex creatives in their own right, such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothy Tanning and Dora Maar.

And it will show surrealism’s contemporary resonances, suggests Marré, citing the surrealist preoccupation with the forest as an echo of modern environmentalism. Surrealism’s anticolonial messages also feature – the Paris exhibition includes artists’ tracts against France’s 1954-62 war in Algeria.

In Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts took the concept of surrealism backwards in time, looking at the links between late 19th-century symbolists and the surrealists, long seen as separate movements.

“There was no real rupture between what happened before and after the first world war,” said Francisca Vandepitte, the curator of the Brussels exhibition, which closed in late July. “Our fundamental approach is trying to show, for the first time, the links,” she said, citing Fernand Khnopff’s austere, somewhat unsettling late 19th-century portrait of his sister as an influence on Magritte’s 1932 work The Unexpected Answer, which shows a person-sized hole in a similarly sterile-looking doorway.

Related: Keeping it surreal: my Dalí-inspired art trip to Catalonia

Many of the works that were on display in Brussels are going to Paris, although the show will continue to evolve as it tours. The Royal Museum of Fine Arts is lending one of the jewels of its collection to Paris: René Magritte’s The Dominion of Light, where a clear blue sky filled with white fluffy clouds frames a row of trees and houses shrouded in nocturnal light. “If only the sun could shine tonight,” went a 1923 Breton poem that Magritte quoted.

But “it is not the classic travelling exhibition”, said Vandepitte. Instead, similar themes will emerge in some, but not of all the museums, themes suggested by Breton’s manifesto: dreams and nightmares, night, forests, the cosmos. “Each partner puts on the exhibition, building on the richness of its own collections and heritage,” she said.

After Paris, the exhibition moves to the Fundacíon Mapfre in Madrid, which will turn the spotlight on surrealists from the Iberian peninsula, such as Dalí and Joan Miró. Then it is on to the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which will explore the heritage of German romanticism, before arriving at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in late 2025 to tell the story of surrealists in the Americas during their second world war exile.

Fleeing the Nazi advance, artists came to the US, Mexico and the Caribbean, where they encountered new influences. In Mexico, for instance, surrealists discovered traditional mythologies about volcanoes, “wonderful fodder for the surrealist mindset”, says Matthew Affron, the curator of the Philadelphia exhibition.

“Someone who sees all five versions [of the exhibition] is going to have a wonderfully varied and broad understanding both of the character of surrealist art, in terms of its themes and styles, [and] its main concerns,” he said.

Perhaps the changing nature of the exhibition is particularly well suited to surrealism in all its strange and transgressive variety. “There is no such thing as surrealist style,” Affron said. “I would say it’s really a philosophy of life, almost, and a mindset. One of the key ideas of surrealism is that we must let the imagination be freed to take us to places that we have not yet been.”

Surrealism is at the Pompidou Centre in Paris from 4 September to 13 January

No comments:

Post a Comment