WOMEN IN SURREALISM

the imagination in the wake of Surrealism

Corneli van den Berg

Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the Masters’ degree

qualification in the Department of Art History and Image Studies in the Faculty

of Humanities at the University of the Free State

Supervisor: Prof E.S. Human

Co‐supervisor: Prof A. du Preez

Date: October 2015

TABLE OF CONTENTS I

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS III

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCING THE IMAGINATION IN THE WAKE OF SURREALISM 1

1.1 DIEGO RIVERA’S LAS TENTACIONES DE SAN ANTONIO 5

1.1.1 Surrealist ‘poetic images’ 8

1.1.2 Shared imagining 10

1.1.3 Hypericonic dynamics 12

1.2 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS 17

1.2.1 Image‐picture distinction 17

1.2.2 Archival approach 19

1.2.3 Chapter overview 20

CHAPTER 2: THE DANGEROUS POWER OF IMAGES – TORMENTING AND SEDUCTIVE IMAGERY IN THE

TEMPTATION OF ST ANTHONY 23

2.1 THE LEGEND OF ST ANTHONY: A TOPOS OF THE IMAGINATION 24

2.2 THE CHRISTIAN SAINT IN PATRISTIC LITERATURE 26

2.3 ST ANTHONY IN EARLY MODERN DEPICTIONS 27

2.4 THE SAINT AS MODERN ARTIST 32

2.5 FLAUBERTIAN ST ANTHONY AND HIS SEDUCTIONS 33

2.6 ST ANTHONY AS A SURREALIST TOPOS 36

CHAPTER 3: THE SURREALIST IMAGINATION 45

3.1 PRODUCTIVE IMAGINING 46

3.2 PERTINENT MOMENTS IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL HISTORY OF THE IMAGINATION 48

3.3 VISIONARY IMAGINING 52

3.4 SURREALIST IMAGING ACTIONS: AUTOMATISM, CHANCE, DREAM & PLAY 54

3.5 ALCHEMY: A SURREALIST METAPHOR 61

3.6 APPROPRIATING SO‐CALLED PRIMITIVISM 64

CHAPTER 4: ON THE EDGE OF SURREALISM: A LATIN AMERICAN CLUSTER OF WOMEN ARTISTS 72

4.1 WOMEN AND SURREALISM 74

4.2 FRIDA KAHLO: AN UNWILLING SURREALIST 77

4.3 REMEDIOS VARO: COSMIC WONDER 82

4.4 LEONORA CARRINGTON: ALCHEMICAL SURREALISM 85

CHAPTER 5: IN THE WAKE OF SURREALISM: SURREALISM IN SOUTH AFRICA 92

5.1 ALEXIS PRELLER: DISCOVERING ARCHAIC AFRICA 95

5.2 CYRIL COETZEE: ALCHEMICAL HISTORY PAINTING 99

5.3 BREYTEN BREYTENBACH: A SURREALIST PAINTER‐POET 103

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION 112

BIBLIOGRAPHY 118

APPENDIX A 132

SUMMARY

Summary

This thesis reports an exploration of various interrelated facets of human imaging and

imagining using the literary and artistic movement, French Surrealism, as catalyst. The ‘wake of Surrealism’ – a vigil held at the movement’s passing, as well as its aftereffects – indicates my primary focus on ideas concerning the imagination held by members of the Surrealist movement, which I trace further in selected artworks of a cluster of women surrealists active in Latin‐America as well as select artists in the South African context.

The Surrealists desired a return to the sources of the poetic imagination, believing that the

so‐called ‘unfettered imagination’ of Surrealism has the capacity to create unknown worlds,

or the potential to envision often startling and strange realities. Not only did members of

Surrealism have a high regard for the imagination, they also emphasised particular

involuntary actions and unconscious functions of the imagination, as evidenced in their use

of the method of automatic writing, dreams, play, objective chance, alchemy and so‐called

primitivism.

In this investigation I follow digital‐archival procedures rather than being in the physical

presence of the artworks selected for interpretation. Responding to this limitation and to

the current interest in image theory, I elaborate a method of art historical interrogation,

based on the eventful and affective power of images. This exploration of the imagination

into Surrealism’s wake therefore also functions as a ‘pilot study’, to determine the viability

of this approach to image hermeneutics. I appropriate and expand W.J.T. Mitchell’s notion

of ‘hypericons’ to develop the proposed concept of ‘hypericonic dynamics’. The hypericonic

dynamic transpires in ‘hypericonic events’, through the cooperative imaging and imagining

eventfulness of the interaction between artist and spectator, mediated by artworks. The

dynamic is especially prominent in artworks with a metapictorial tenor.

With hypericonic dynamics and metapictorial thematics as my heuristic method, I

investigate artworks by three women surrealists – Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington – living and working in Latin‐America after the Second World War, and after the French Surrealist movement had already experienced its decline. Against the backdrop of indigenous visual culture their distinct individual styles are also related to Magical realism in the Latin‐American literary context, a style which overlaps and intersects with Surrealism. I expand upon insights gained in investigating the women in Mexico, to determine whether select South African artists, Alexis Preller, Cyril Coetzee, and Breyten Breytenbach belong in the wake of Surrealism.

The central aim of my exploration of the imagination is to gain a deeper understanding of

the everyday human imagination and its myriad operations in daily life, for the greater part

conducted below the threshold of consciousness. The imagination is a universal human

function, shared by all, yet also operational at an individual level. It also performs a unique

function of image creation in the specialised domain of the fine arts. I understand the

imagination to be irreducible, while often working in a subconscious, involuntary, and

supportive, but nevertheless primary manner in everyday human life.

Keywords:

Surrealism, imagination, image studies, Bildwissenschaft, metapictures, hypericons, ‘power

of images’, ‘hypericonic dynamics’, St Anthony, women surrealists.

INTRODUCTION

In this thesis I aim to explore various interrelated facets of human imaging and imagining

using the literary and artistic movement, French Surrealism, as a catalyst for this

investigation. I propose Surrealism, with its emphasis on highly imaginative and challenging

artistic creations, can be a valuable springboard for studying human imaging and imagining

capabilities and activities, both artistic and non‐artistic.

For a period of approximately two decades, Surrealism was one of the dominant

movements of the modernist avant‐garde in Europe.1 Although situated, diachronically,

within the modernist avant‐garde, the Surrealist movement followed its own historical

trajectory. In contrast to what one could term Greenbergian ‘mainstream modernism’, and

its predominantly formalist rush toward aesthetic autonomy in the various forms of non‐

figurative expressionism, constructivism, and minimalism, and the search for aesthetic

purity, Surrealism was interested in researching the roots of the imagination, in the

subconscious and dreaming.2

The surrealist period style or time‐current took form and solidified into the French Surrealist

movement with the publication of André Breton’s First Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924.3

Various authors, including Theodor Adorno in his 1956 essay Looking back on Surrealism,

remark on the fact that French Surrealism did not survive the Second World War. Reasons

given for this termination include the fact that most of the group’s members no longer

resided in Paris, having become exiles in America during the war, and since the changes in

bourgeois society that they had called for, after the destruction of the Great War, no longer

applied (Adorno 1992: 87).4

Therefore, the French movement can be described as having a reasonably well‐defined

beginning and ending.

1 Cf. Poggioli (1968), Calinescu (1977), Bürger (1984).

2 Abstraction, grounded in the early twentieth century work of Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, was,

according to Cheetham (1991: xi) the most daring and challenging development to occur in Western painting

since the Renaissance. Abstraction, or the search for the aesthetic ideology of purity, had crucial consequences

for all aspects relating to art – for art ‘itself’, its creation and embodiment, as a model for society, and – closely

related – for art as a political force (Cheetham 1991: 104).

3 When I am referring to the core French group the terms ‘Surrealism’ or ‘Surrealist’ will be spelled with a

capital ‘S’. I indicate the broader ‘surrealist’ dynamic or time‐current, and the wake of ‘surrealism’, by using a

lowercase ‘s’.

4 Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School were also exiled in America, until eventually becoming

disenchanted with the so‐called progressive free West, and returning to Germany.

2

still be alive and endure (Breton 2010: 35, 129).

5 Maurice Nadeau, Surrealism’s premier

historian, allows that the movement might have failed in achieving the societal revolution it

had called for, but denies that it is dead, believing the surrealist attitude or mind‐set to be

“eternal” (Nadeau 1965: 35).

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query SURREALISM. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query SURREALISM. Sort by date Show all posts

Friday, February 14, 2020

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s Art, Politics, and the Psyche

A LOCAL TEXT FROM EDMONTON WHERE THE U OF A IS LOCATED

AUTHOR: Steven Harris, University of Alberta

DATE PUBLISHED: January 2004

AVAILABILITY: Available

FORMAT: Hardback

ISBN: 9780521823876

This volume examines the intersection of Hegelian aesthetics, experimental art and poetry, Marxism and psychoanalysis in the development of the theory and practice of the Surrealist movement. Steven Harris analyzes the consequences of the Surrealists' efforts to synthesize their diverse concerns through the invention, in 1931, of the "object" and the redefining of their activities as a type of revolutionary science. He also analyzes the debate on proletarian literature, the Surrealists' reaction to the Popular Front, and their eventual defense of an experimental modern art

Review

"Excellent...an example of how good art history can be. Thorough research of primary sources and intelligent grounding in social history is accompanied by genuinely illuminating interpretations of specific works." CAA Reviews

"It makes a significant contribution to the understanding of how and why surrealism changed in the 1930's."

GOOGLE BOOKS

Steven Harris

Cambridge University Press, Jan. 26, 2004 - Art - 342 pages

This volume examines the intersection of Hegelian aesthetics, experimental art and poetry, Marxism and psychoanalysis in the development of the theory and practice of the Surrealist movement. Steven Harris analyzes the consequences of the Surrealists' efforts to synthesize their diverse concerns through the invention, in 1931, of the "object" and the redefining of their activities as a type of revolutionary science. He also analyzes the debate on proletarian literature, the Surrealists' reaction to the Popular Front, and their eventual defense of an experimental modern art.

CAA BOOK REVIEW

June 11, 2004

Steven Harris Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s: Art, Politics, and the PsycheNew York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 340 pp.; 35 b/w ills. Cloth $108.00 (0521823870)

Steven Harris’s new book on Surrealism is excellent. It is refreshing to see the politics of Surrealism properly acknowledged, and, at the same time and as part of the same argument, to see the aesthetics that underwrote those politics correctly assessed. In Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s: Art, Politics, and the Psyche, Harris tracks an extremely rich and nuanced discourse between Surrealism and the French Left, a series of debates virtually unknown in Anglophone culture; he also nicely lays out his arguments in clear and readable prose. But the real issues at stake in this discourse are difficult to convey to a contemporary audience bred on the simplistic and misleading accounts of Surrealism found in much of the literature. Virtually all histories of Surrealism on this side of the Atlantic persist in viewing it as an art movement, and in looking at Surrealist works as if they were only art. Though Surrealist research often resulted in art, it did not start that way. For any understanding of the potentials of modern art, of modernism’s past dreams and future possibilities, it is crucial to consider fully what the Surrealists were trying to do.

As an avant-garde movement, Surrealism aimed to surmount the anodyne role of art as a provider of “spiritual” experiences that make a false life bearable, and to overcome the specialist function of the artist. These goals were frequently and plainly stated in manifestos and articles in Surrealist publications, but mainly expressed in the Surrealist artworks themselves. The most critical social position was presented in sensuous form, in an appeal to the imagination and the poetic faculty, not in the dry and all-too-literal polemics that we are familiar with today. A failure to realize this might be one of the reasons why Surrealism is not entirely understood today. Harris performs the task of elucidation that we evidently need, makes very concrete and illuminating readings of enigmatic and ambiguous works, and traces a chronology of Surrealist activity that allows all the points and sharpened edges in its polemic to emerge to the touch once more.

The Surrealists wanted to understand the relation between subjectivity and the world, between the inner and outer realms of experience. On the surface, their quest seems too general, too vague to generate useful answers; yet the importance of line of research is that it has political and aesthetic and psychological ramifications. It can reduce to matters of artistic technique (an artwork might be constructed according to an objective system or be the product of a series of decisions by the artist), or to problems in interpretation (such as the question of how much weight to give to intention), but for the Surrealists the fundamental issue was the role of the intellectual in modern society. This issue also set the music for the Surrealists’ complicated dances with the French Communist Party.

The great merit of Harris’s book is that it brings forward the philosophical researches of André Breton and the others, most profoundly their speculation on the connection between mind and matter. The question was left unsolved—perhaps it is unsolvable—but for the Surrealists it was capable of generating concrete outcomes. Harris argues that the Surrealists based their investigations most importantly on Hegel, particularly his notion that, in both the romantic and modern eras, art must become knowledge. This notion so contradicts the popular, widely disseminated view of Surrealism that it deserves a double take. The Surrealists saw their activity as research into the operations of the mind, in order to understand how the imagination works; they did not want to traffic in obscurities. Judging from Harris’s bibliography (of studies published mostly in French), some work has been done on Hegelianism in Surrealist thought, and therefore the subject is not Harris’s main focus. Yet, as the author suggests in his introduction, the recent interest in Georges Bataille, fostered partly by the editors of October, has brought with it a one-sided derogation of Breton and an obscured appreciation of his critical and dialectical appropriation of Hegel. The Surrealists were not in any way idealist; their Hegelianism was materialist, Marxist, and, one might even say, negative. In other words, there may be more similarities between Breton and Theodor Adorno than first meets the eye. The Surrealists were not looking for false resolutions, but for openings toward the future.

Harris does not pursue the Hegelian strand as far as I, for one, might wish. Among other things, I came to the book to gain a better understanding of where the Surrealists thought the boundaries of consciousness lay. That topic, however, might belong more to the 1920s and the theoretical context of Breton’s novel Nadja. As the book’s title indicates, Harris’s period is the 1930s, and so inevitably must entail a close study of the political discourse of the movement. But if his study manages to put the Bretonian core of Surrealism back on the table in an unfamiliar way, namely through its politics, it also opens up an extremely rich body of aesthetic and political thought virtually unknown in the English-speaking art world. For myself, I knew that Salvador Dalí was an important thinker, but I did not realize how rigorous, how polemical, and how taken up with the political agenda of the group, at least in his early period, he was. Likewise, I have some familiarity with Roger Callois from reprints of his writings in October, but also without an inkling of the real nature of his importance at the time. But the real surprises were Claude Cahun and Tristan Tzara.

Tzara, the former Dadaist who famously declared that “thought begins in the mouth,” turns out to be a committed Marxist who broke with Surrealism because he felt that automatism had degenerated into mystification. According to Harris, “The waking dream is for Tzara … consciously Hegelian in its attempt to synthesize and incorporate the rational and the irrational in a new mode of thought” (128). Cahun is even more surprising. Her photos are now well known and she is generally seen as a Cindy Sherman avant-la-lettre, but as Harris demonstrates, she was one of the sharpest, most passionate and literate of leftists, as well as a strong presence at the center of the Surrealist group. Her writing must now be essential in any history of twentieth-century art and theory.

Cahun appears here not as a photographer, but as a writer and maker of objects. Harris’s book is built around the Surrealist object, whether assemblage, found, or readymade. He focuses on two important occasions: objects published and discussed in the December 1931 issue of Le Surréalisme au service de la Révolution, and in the Exposition Surréaliste d’Objets, held in May of 1936 at the Galerie Charles Ratton (the latter perhaps the central moment in his history). Harris tracks changes in the conceptualization of the object in Surrealist literature, but he also shows how the objects themselves constitute interventions in an ongoing debate. Furthermore, he has evidently studied the works closely and consequently has a lot of very interesting things to say about how they are made and what they mean.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s is an example of how good art history can be, and it reaches this level because thorough research of primary sources and intelligent grounding in social history is accompanied by genuinely illuminating interpretations of specific works. It is rare that an art historian today can marshal the whole orchestra so that all the sections play together and in tune. It is the tuning that is crucial, by which I mean an ear for the note that matters, in a text or a work. If I have one criticism of Harris’s book, it is that his prose is not perfect music—but that is excusable considering the constraints and pressures of a graduate dissertation. In comparison to any other example of that genre that I have read, Harris’s book is superior. It covers a lot of material without losing focus; it does justice to the specificity of the artwork without losing sight of the politics that surround it; the writing is polemical and participates in current debates while maintaining a scholarly posture defended by rigorous historical argument. This book deserves to be noticed, and read.

Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Arts, University of Waterloo

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s

Published: SEPTEMBER 14, 2005

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s: Art, Politics, and the Psyche. By Steven Harris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 328 pages. 35 b+w illustrations.

Whether due to a sense of convenience or to partisan docility, too many intellectuals regard and represent the social revolution as either completed or unrealizable. It is time to rise up against such a misunderstanding of the realities that surrounds us, and of the determinism that governs them. (225)

Cited in the journal Clé

November or December 1938.

In his new book, adapted from his doctoral dissertation from the University of British Columbia, University of Alberta art historian Steven Harris analyzes one of the most complex and fraught moments in the history of the avant-garde and of twentieth century art in general. Harris’s primary intent “is to understand the development of surrealist thought and activity at a moment when, in its second period from 1929-1939, it was able to catch a glimpse of what the implications of its radical aesthetic project might be, at the time of its most active and searching attempt to synthesize Hegelian aesthetics, psychoanalysis, and Marxism.”(2) What is notable about Harris’s approach to surrealism is that, unlike other writers on the subject, he attempts, largely successfully, to weave together the Hegelian, psychoanalytic, and Marxian themes in his own methodology, thus illuminating the cultural and political significance of surrealism, especially for the members of the group allied with André Breton. Harris’s analysis diverges not only from the Kantian-inflected interpretations of surrealism found in such diverse writers as Jürgen Habermas, Jean-François Lyotard, and Clement Greenberg but also from the more heavily psychoanalytic approach found within the writers around the journal October. While the secondary literature on surrealism has been rapidly expanding in the past two decades, Harris’s book is such a welcome addition to the literature thanks to his desire to focus, not just on the formal aspects of the objects produced by surrealists or on the politics of the surrealists, but rather on the twin poles of art and politics in a constant productive tension with one another. While bearing a superficial similarity to certain transgressive and hybridizing strategies in postmodernist and post-colonialist critiques Harris’s foregrounding of the Hegelian element in both his analysis and methodology declares his distancing from the theoretical models of the recent past.

An example of both the similarities and differences within the modernist-postmodernist debates on the question of the avant-garde and surrealism is captured in the work of Jürgen Habermas and Jean-François Lyotard. In perhaps his most widely read essay dealing with questions of aesthetics and the avant-garde, entitled “Modernity – An Incomplete Project” Habermas summarized the diverse approaches within surrealism to overcome and level the barriers between art and life, fiction and praxis, appearance and reality to one plane or “the attempts to declare everything to be art and everyone to be an artist, to retrace all criteria and to equate aesthetic judgement with the expression of subjective experiences – all these undertakings have proved themselves to be sort of nonsense experiments.” Surrealism makes two strategic errors from Habermas’s perspective: first, failure of the surrealist revolt arises when the attempt to integrate the autonomous cultural sphere into life disperses its contents but there is no resultant emancipatory effect. Secondly, Habermas argues that the focus of the surrealists on dissolving the sphere of the aesthetic-expressive merely replaces one abstraction with another precisely because “a reified everyday praxis can be cured only by creating unconstrained interaction of the cognitive with the moral-practical and the aesthetic-expressive elements. Reification cannot be overcome by forcing just one of those highly stylized cultural spheres to open up and become more accessible.” Harris, by foregrounding the Hegelian aspect of the surrealists, demonstrates that Breton is emphasizing the imagination over the rational but not merely advocating “nonsense experiments”. In the combination of psychoanalysis and Hegel, the surrealist objects of the mid-1930s reveal that “the use of Hegel becomes the occasion for the end of art anticipated in his own aesthetics (as art becomes reflection), but this occurs through a reinvestment of desire in the object, rather than through a more conscious, rational approach. Art does not become pure Idea as it approaches philosophy; rather, it retains a sensual dimension through the poetic imagination, to which it returns with the aid of Freud, in a contestation of the purity and autonomy of modern art.” In his analysis Harris, reveals the inadequacy of Habermas’s formulation of surrealism, in particular, and by broader implication the limitations of his understanding of the role of art and the avant-garde within modernity.

By contrast, in the work of the postmodernist Jean-François Lyotard the work of the avant-garde art practices are valued for their ability to explore the sublime but sideline the Hegelian impetus of the surrealist avant-garde to hold onto the tension between the artistic and political realms. Lyotard argues, “Burke’s elaboration of the aesthetics of the Sublime, and to a lesser degree Kant’s, outlined a world of possibilities for artistic experiments in which the avant-gardes would later trace out their paths.” In opposition to Habermas advocacy of the communicative role outlined for the aesthetic-expressive sphere, Lyotard advocates for the avant-garde to abandon “the role of identification that the work previously played in relation to the community of addressees.” The avant-garde becomes wedded to an investigation of the `unrepresentable’ within the Kantian notion of the sublime or, as Lyotard himself argues, “our business is not to supply reality but to invent allusions to the conceivable which cannot be represented”. Lyotard attacks both Hegel and Habermas at the end of his essay on “What is the Postmodern” by arguing that “it is not to be expected that this task will effect the last reconciliation between language-games (which, under the name of faculties, Kant knew to be separated by a chasm), and that only the transcendental illusion (that of Hegel) can hope to totalize them into a real unity.” Hegel and Habermas are pilloried for their willingness to embrace the terror of such totalizing errors. I would argue that Harris’s investigations into the surrealist object reveal a more nuanced understanding of surrealism and the avant-garde than that of either Habermas or Lyotard in re-establishing the legitimacy of the Hegelian dimension in the surrealist object as neither a “nonsense experiment” or as merely an exploration of the sublime.

Given the intensity of the debates over the legacy of modernism and postmodernism in the visual arts over the last three in recent decades on the relationship between art and politics, Harris adroitly balances the nuances of politics, aesthetics, and psychoanalysis. In his analysis, Harris places his emphasis on an immanent engagement with his subject, thus enabling him to see in surrealism an important exploration in the attempt to found another culture. In other words he notes, in the 1930s, “[surrealist] art was no longer simply art, the production of rarefied commodities for connossieurs,” but actually, “reconceptualized as a kind of science – that other autonomous sphere of human endeavour – as a form of experimental research contributing to a greater knowledge of human thought.” “Art would no longer be,” in Harris’s words,” what it had been hitherto, a separate art belonging to a dying culture, but would realize itself in becoming something that would make a real contribution to the present and the future, both in re

alizing its true nature as unconscious thought – the source of imagination, in this psychoanalytic understanding – and in the interpretation of such works in the interests of knowledge.”(3) Harris places the emphasis on an imminent critique of surrealism while yet maintaining the dynamic inter-action between art and politics. This is an indication, perhaps, of Harris’s greatest departure from one of the most significant schools of thought on surrealism; that of the October group of critics and historians. While he acknowledges the important work of Rosalind Krauss, Hal Foster, and Denis Hollier, Harris is very careful to emphasize his own perspective, residing more on the side of the historical and dialectical as opposed to the more `theoretical’ and psychoanalytical approach of the New York critics. For example, from Harris’s perspective, Foster’s symptomatic reading of Surrealism leaves out “the movement’s inter-textual relation to art and literature of its time, and its valorization of science as a supersession of these categories.” (117) Harris especially challenges the work of Krauss and Hollier for its uncritical acceptance of Georges Bataille’s description of the surrealists as `Icarian idealists’ in relation to his own `base materialism.'(9) Thus on the important questions of surrealism’s relation to modernism, the role of sublimation or desublimation, or its use of poetry, Harris’s analysis is an important and valuable departure from the October group’s analysis and procedures.

Harris has composed the book in five chapters beginning with a key investigation of the prototypical surrealist objects in 1931 which embody, as Harris notes, “the first moment of the object’s invention in relation to the imperative to go `beyond painting.'”(6). However, Harris reminds us that it is vital to remember that “the object still bore a critical relation to cubist assemblage; the claim to be an avant-garde position was manifested precisely in this `au-dela’.” Therefore Harris rightly asserts, “It is the objects’ critical relation to the dominant categories of art making that is important here, rather than their mere rejection; there is an attempt to sublate what are understood to be the progressive aspects of modern art – in particular, the principle of collage and the experimental nature of prewar modernism – into the object, which is understood at the same time to be antiformal and antiaesthetic in its rejection of the claims for autonomy made by the partisans and practioners of modern art.”(6) However, by seeking to go beyond painting and traditional aesthetics surrealism required an alliance with a potentially revolutionary political avant-garde to effect a reconciliation between art and life. Harris documents in his second chapter the difficult task of the surrealists in the 1930s to achieve recognition as an avant-garde in the cultural sphere by the leaders of the revolutionary avant-garde in the Communist Party of France. Without this recognition the surrealists pretensions to being a new revolutionary avant-garde would dissolve. Harris highlights in chapter three the effort to reframe the surrealist object as scientific research, as opposed to aesthetic experimentation, which challenged the unity of the movement and even the definition of what surrealism was meant to represent. Chapter four focuses upon the break with the Communist Part in 1935 and the relationship between surrealism and the Popular Front. Finally, a key moment for the expression of the surrealist approach to the tension between art and politics, the exhibition of surrealist objects in the Exposition surréaliste d’objects, is the focus of the fifth chapter entitled “Beware of Domestic Objects: Vocation and Equivocation in 1936”. Lacking access to the revolutionary avant-garde but desiring to remain critical, the interrelationship of art and dream so essential to surrealist aspirations remains, especially in key objects like Jacqueline Lamba’s and Andre Breton’s Le Petit Mimétique, “but it no longer promises the reconciliation of rational and irrational, nor the overcoming of art in a generalized creativity for which the object would furnish a model.” Criticality is salvaged but at a tremendous price; “its preservation as a separate activity somewhat paradoxically represents a delay in the reconciliation of art and life.” However, as Harris notes, shortly thereafter, “once surrealism resituates itself within the field of modern art,” the surrealist project becomes “unviable in the present.”(218)

The emphasis of Harris’s self-declared dialectical and immanent critique of surrealism is on weaving the two poles of art and politics into a more sophisticated relationship with one another than has hitherto been attempted by art historians. He foregrounds the productive tension between art and politics in a manner that has important ramifications for the future study of surrealism but also for contemporary art production that wishes to explore the range of questions concerning the relationship of art to the political raised in such an intelligent manner by the surrealist movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Harris targets exactly the crucial moment within the history of surrealism that signals the shift, “from a confidence in the self-sufficiency and superiority of an autonomous, unconscious thought process (such as is expressed in automatic writing and other surrealist techniques), to an acknowledgement of the interdependence of thought and the phenomenal world. This was in keeping with an imperative shared by many revolutionary intellectuals in the 1930s to make thought active, to relate the hitherto separate spheres of thought and action, action and dream, a separation that had been understood to be the hallmark of a separate, modernist art and literature since the time of Baudelaire.”(2) However, I believe that, in the aftermath of decades of intellectual combat between modernists and postmodernists, and especially in the aftermath of September 11, 2001 and the invasion of Iraq, what is most welcome in Harris’s analysis of surrealism are the questions concerning the fraught relationship between culture and politics that he raises in a new and provocative way. These questions have been ignored for too long by too many art and cultural historians as well as producers of contemporary art because of the antipathy of many modernists, postmodernists, and poststructuralists towards Hegel and what they regard as the authoritarian and homogenizing meta-narratives of his approach. Perhaps this book signals, at last, an awakening to the critical efficacy and non-totalitarian potential of a combined Marxist, Hegelian, and psychoanalytic approach to culture and politics that momentarily bloomed in the 1930s. Is the surrealist object, as outlined by Harris, any more viable today than it was in the cataclysm of the 1930s? This question has yet to be resolved.

David Howard is an Associate Professor of Art History at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

This entry was posted in Miscellaneous and edition 2005 Issue 3 . Bookmark the permalink. Both comments and trackbacks are currently closed.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s: Art, Politics and the Psyche by Steven HarrisPatricia Allmer 28 Jun 2004

"A strong, well-illustrated analysis and a highly complex picture of Surrealism in the 1930s." Pop MattersThe co-option of the movement into modern mass culture is overwhelming, a testament to its genuinely threatening force.

SURREALIST ART AND THOUGHT IN THE 1930S

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Length: 340

Subtitle: Art, Politics and the Psyche

Price: $90 (US)

Author: Steven Harris

UK PUBLICATION DATE: 2004-02

AMAZON

The art object lies between the sensible and the rational. It is something spiritual that appears as material.

Length: 340

Subtitle: Art, Politics and the Psyche

Price: $90 (US)

Author: Steven Harris

UK PUBLICATION DATE: 2004-02

AMAZON

The art object lies between the sensible and the rational. It is something spiritual that appears as material.

Hegel's Poetics and the beginning of Breton's 1935 lecture 'Situation Surréaliste de l'Objet'

Surrealism was arguably the only truly revolutionary art movement of the 20th century. Contemporary culture, from advertising to pop videos to film to political spin to t-shirts, repeatedly uses Surrealist devices, methods, and iconography. The co-option of the movement into modern mass culture is overwhelming, a testament to its genuinely threatening force. Steven Harris, assistant professor of Art History at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, tries in Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s to reposition the movement in some of its original contexts.

The book researches Surrealism in its second period, from 1929-1939, and offers long and detailed scholarly engagement, attempting to capture thirties Surrealism as a collaborative movement, as well as shedding light on Surrealist attempts and failures at bringing together and synthesising Hegelian aesthetics, psychoanalysis and Marxism. As this might suggest, this is a demanding but rewarding work, shedding new light on a perennially popular area of art history.

Recent writings on Surrealism have, to a large extent, focused on Surrealism's preoccupation with psychoanalysis, as well as the analysis of Surrealism's own "unconscious." The leading figures and, perhaps, initiators of this trend are the group of art theorists linked to the journal October. Formed in 1976, October members such as Rosalind E. Krauss, Hal Foster and Denis Hollier have revolutionised the art historical world by introducing post-structuralist theories into modern thinking on art.

Part of Harris's project is to argue with October's psychoanalysis of Surrealism (specifically their reliance on the controversial theories of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan), some of which, he suggests, "runs counter to some of the movement's own claims." Harris argues that Surrealism is a dynamic field in which theoretical constituents (psychoanalysis, Marxism, Hegelianism) battle, causing friction between each other as well as interacting in centrifugal and centripetal ways through "Hegelianising psychoanalysis" and "Freudianising Marxism."

Another argument with the October group is their positioning of French writer and philosopher Georges Bataille as a Surrealist. Instead, Harris argues that Bataille becomes, in the 1930s, "materialist in antithesis to Surrealism's projected idealism, realist in antithesis to its Surrealism, and antidialectical in opposition to its dialectics," whilst his 1930 essay on Surrealism "is too often accepted uncritically as an adequate description of Surrealism."

The Surrealist object -- things found or recovered from flea-markets, junk shops, even from the gutter, and reinvested with aesthetic importance -- lies for Harris at the heart of Surrealism in the 1930s, and embodies "many of the aspirations of the group in this period." The Surrealist object, the first of which was Alberto Giacometti's highly erotic Boule Suspendue in 1931, and which attained its most significant moment in the Exposition surréaliste d'objets in 1936, becomes in Harris's book a fragment encapsulating and telling the story of Surrealism's second period.

It is the evidence of an attempt to move beyond painting: "The Surrealist object is … situated beyond the traditional artistic categories of painting or sculpture, and it participates in the logic of a scientific activity that would also be disruptive and revolutionary, as an activist intervention allied to (but not identical to) the activities of the political avant-garde." Following this, his theoretical elaborations never lose sight of the Surrealist object, as object of investigation and revelation. His arguments are underlined by detailed interpretations of objects offered by a wide range of artists such as Claude Cahun, Valentine Hugo, Man Ray, Juan Miró, Oscar Dominguez, Méret Oppenheim and André Breton.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s is concerned with the Surrealist attempt to integrate or synthesise art into life. Harris explores the movement from an original "overcoming of the separation of art and life in a 'poetry made by all, not by one'" to the end of this aspiration by 1938, where the "overcoming of art is exchanged for the persistence of art." Here the Surrealist object is seen as the "object of the object," as the "leading example offered by the Surrealists of this art that would no-longer-be-art... since in their understanding it was a realization and an articulation of the relation between subject and object, action and dream."

One criticism of Harris's book is its lack of geographical range. For example, he remains very focussed on Surrealism in France, and manages to go 321 pages without mentioning Belgian Surrealism and its relation to and conceptualisation of the Surrealist object as understood by French Surrealist artists. So, for example, René Magritte produced numerous objects from 1931 onwards, such as his painted plaster cast Les Menottes de Cuivre (1931), his painted casts of Napoleon death masks L'Avenir des Statues (c. 1932) or his painted bottles like Femme-Bouteille (1940). Questions such as how these objects differ from, relate to, enrich or challenge the specifically French conceptions of the Surrealist object are never addressed.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s is a rigorously written and highly academic book, which redirects attention from a principally psychoanalytical approach to understanding Surrealism, positing instead an evolving, dynamic movement caused by the interaction of often contradictory theoretical forces. Harris relentlessly returns to the different arguments he sets out in the book, and through this he links them together into a strong, well-illustrated analysis and a highly complex picture of Surrealism in the 1930s.

SURREALIST ART AND THOUGHT IN THE 1930S STEVEN HARRIS

Surrealism was arguably the only truly revolutionary art movement of the 20th century. Contemporary culture, from advertising to pop videos to film to political spin to t-shirts, repeatedly uses Surrealist devices, methods, and iconography. The co-option of the movement into modern mass culture is overwhelming, a testament to its genuinely threatening force. Steven Harris, assistant professor of Art History at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, tries in Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s to reposition the movement in some of its original contexts.

The book researches Surrealism in its second period, from 1929-1939, and offers long and detailed scholarly engagement, attempting to capture thirties Surrealism as a collaborative movement, as well as shedding light on Surrealist attempts and failures at bringing together and synthesising Hegelian aesthetics, psychoanalysis and Marxism. As this might suggest, this is a demanding but rewarding work, shedding new light on a perennially popular area of art history.

Recent writings on Surrealism have, to a large extent, focused on Surrealism's preoccupation with psychoanalysis, as well as the analysis of Surrealism's own "unconscious." The leading figures and, perhaps, initiators of this trend are the group of art theorists linked to the journal October. Formed in 1976, October members such as Rosalind E. Krauss, Hal Foster and Denis Hollier have revolutionised the art historical world by introducing post-structuralist theories into modern thinking on art.

Part of Harris's project is to argue with October's psychoanalysis of Surrealism (specifically their reliance on the controversial theories of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan), some of which, he suggests, "runs counter to some of the movement's own claims." Harris argues that Surrealism is a dynamic field in which theoretical constituents (psychoanalysis, Marxism, Hegelianism) battle, causing friction between each other as well as interacting in centrifugal and centripetal ways through "Hegelianising psychoanalysis" and "Freudianising Marxism."

Another argument with the October group is their positioning of French writer and philosopher Georges Bataille as a Surrealist. Instead, Harris argues that Bataille becomes, in the 1930s, "materialist in antithesis to Surrealism's projected idealism, realist in antithesis to its Surrealism, and antidialectical in opposition to its dialectics," whilst his 1930 essay on Surrealism "is too often accepted uncritically as an adequate description of Surrealism."

The Surrealist object -- things found or recovered from flea-markets, junk shops, even from the gutter, and reinvested with aesthetic importance -- lies for Harris at the heart of Surrealism in the 1930s, and embodies "many of the aspirations of the group in this period." The Surrealist object, the first of which was Alberto Giacometti's highly erotic Boule Suspendue in 1931, and which attained its most significant moment in the Exposition surréaliste d'objets in 1936, becomes in Harris's book a fragment encapsulating and telling the story of Surrealism's second period.

It is the evidence of an attempt to move beyond painting: "The Surrealist object is … situated beyond the traditional artistic categories of painting or sculpture, and it participates in the logic of a scientific activity that would also be disruptive and revolutionary, as an activist intervention allied to (but not identical to) the activities of the political avant-garde." Following this, his theoretical elaborations never lose sight of the Surrealist object, as object of investigation and revelation. His arguments are underlined by detailed interpretations of objects offered by a wide range of artists such as Claude Cahun, Valentine Hugo, Man Ray, Juan Miró, Oscar Dominguez, Méret Oppenheim and André Breton.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s is concerned with the Surrealist attempt to integrate or synthesise art into life. Harris explores the movement from an original "overcoming of the separation of art and life in a 'poetry made by all, not by one'" to the end of this aspiration by 1938, where the "overcoming of art is exchanged for the persistence of art." Here the Surrealist object is seen as the "object of the object," as the "leading example offered by the Surrealists of this art that would no-longer-be-art... since in their understanding it was a realization and an articulation of the relation between subject and object, action and dream."

One criticism of Harris's book is its lack of geographical range. For example, he remains very focussed on Surrealism in France, and manages to go 321 pages without mentioning Belgian Surrealism and its relation to and conceptualisation of the Surrealist object as understood by French Surrealist artists. So, for example, René Magritte produced numerous objects from 1931 onwards, such as his painted plaster cast Les Menottes de Cuivre (1931), his painted casts of Napoleon death masks L'Avenir des Statues (c. 1932) or his painted bottles like Femme-Bouteille (1940). Questions such as how these objects differ from, relate to, enrich or challenge the specifically French conceptions of the Surrealist object are never addressed.

Surrealist Art and Thought in the 1930s is a rigorously written and highly academic book, which redirects attention from a principally psychoanalytical approach to understanding Surrealism, positing instead an evolving, dynamic movement caused by the interaction of often contradictory theoretical forces. Harris relentlessly returns to the different arguments he sets out in the book, and through this he links them together into a strong, well-illustrated analysis and a highly complex picture of Surrealism in the 1930s.

SURREALIST ART AND THOUGHT IN THE 1930S STEVEN HARRIS

Monday, July 29, 2024

Paris exhibition celebrates global spread of surrealism

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels

Sun, 28 July 2024

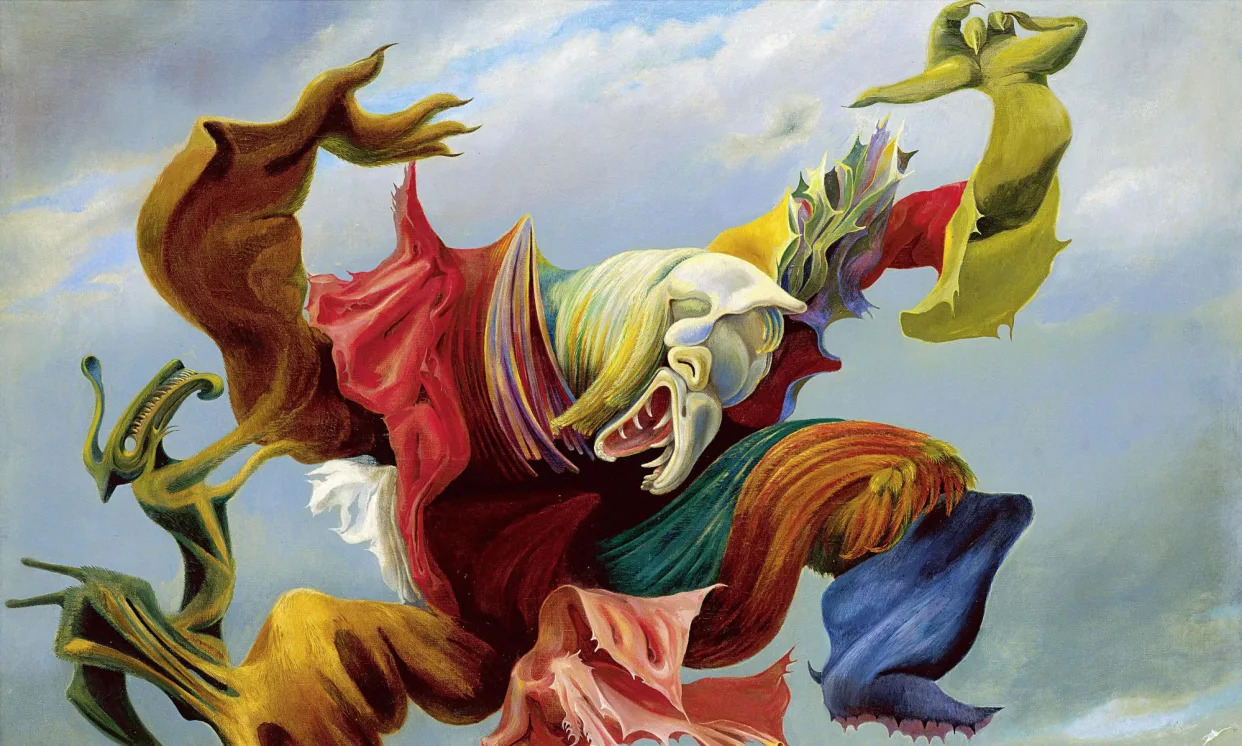

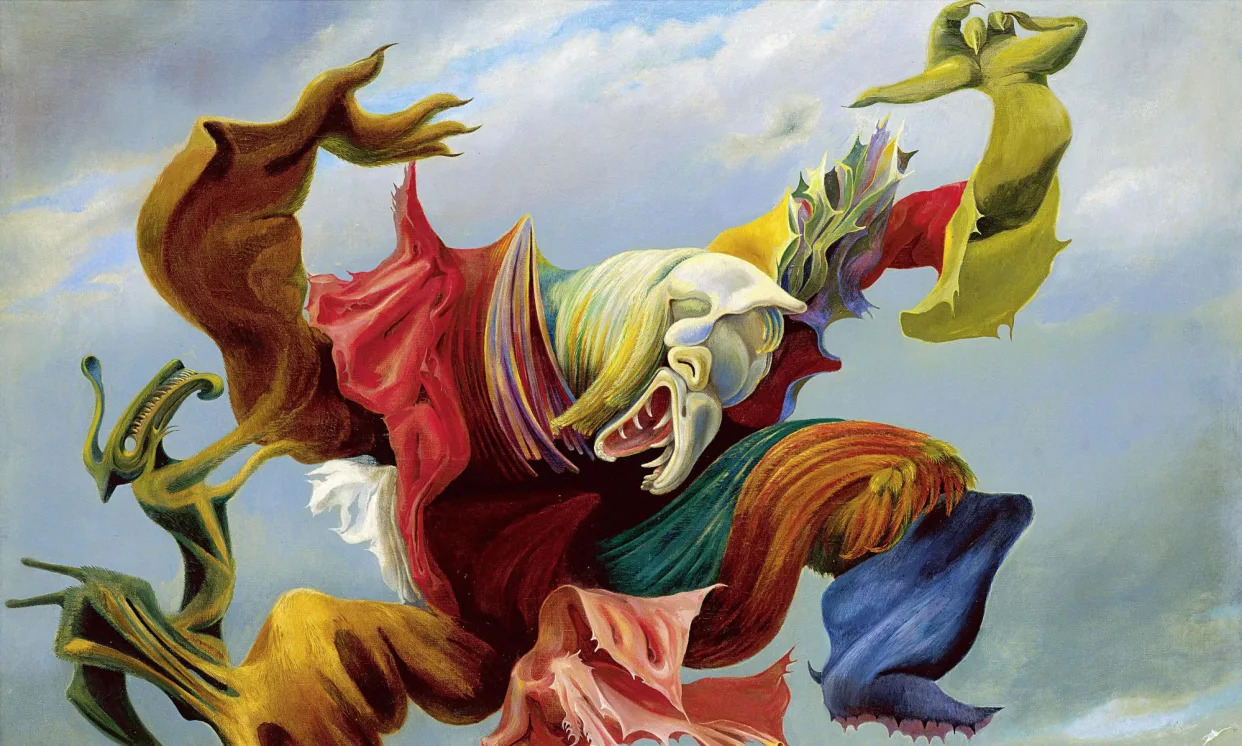

Max Ernst: The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism)

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels

Sun, 28 July 2024

Max Ernst: The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism)

.Photograph: Classicpaintings/Centre Pompidou

One hundred years ago, in a tiny studio flat in a bohemian district of Paris, a former medical student turned writer set out to define surrealism “for once and for all”. In his Manifesto of Surrealism André Breton called for a new kind of art and literature fired by the unconscious, “the dictation of thought free from any control by reason, exempt from aesthetic or moral preoccupation”.

Far from settling surrealism “for once and for all”, the handwritten document was a departure point for a sprawling, subversive movement of bad dreams, haunting landscapes, fantastical alien creatures, unsettling portraits and visual tricks. Now, a century later, a major exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, opening in September, will celebrate how surrealism spread around the world, far beyond the environs of the French capital.

The Paris exhibition is the second in a sequence of five. The show opened in Brussels and will move on to Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia in 2025. Organisers say it is an unprecedented way to organise an exhibition: while some works and themes remain constant in each city, others change and each museum tells its own story.

Perfect, then, for a movement that always aimed to subvert traditional artistic norms.

When the Pompidou Centre last held a major exhibition on surrealism in 2002, it was characterised as an essentially European movement emanating from a group in Paris. Since then, a great deal of research by universities and museums has enlarged that view, said Marie Sarré, the curator of the show at the Pompidou Centre, the organisation that initiated the project. “This exhibition, on the centenary, aims to show surrealism in all its diversity,” she said.

“It is important to remember that surrealism was a movement that spread – and this is exceptional for an avant-garde movement – around the world, in Europe, but also the United States, South America, Asia and the Maghreb.”

What unites all these artists is Breton’s call to live by the imagination, she suggests. “There is this attention to the wondrous in everyday life. [Surrealism] wants to provoke, to shock, [to show] the wonderful aspect of everyday life that comes from consciousness or access to dreams.”

At the heart of the exhibition will be Breton’s first manifesto, with pages of the original manuscript on display, in a loan from the French national library, which acquired the document in 2021 after it was declared a national treasure.

The emblematic names of the surrealist movement will be present, with works by René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. But visitors will find less well-known figures, such as Japanese artist Tatsuo Ikeda, whose art evoked the horrors of war and the toxic consequences of Japan’s postwar reindustrialisation, and Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican painter active in the middle of the 20th century, who is credited with fusing modernism with pre-Columbian motifs in vividly coloured works.

Reflecting a growing tendency, the Pompidou Centre restores to view neglected female artists, who were long reduced to girlfriends and muses with colourful bit parts in the surrealist story, rather than complex creatives in their own right, such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothy Tanning and Dora Maar.

And it will show surrealism’s contemporary resonances, suggests Marré, citing the surrealist preoccupation with the forest as an echo of modern environmentalism. Surrealism’s anticolonial messages also feature – the Paris exhibition includes artists’ tracts against France’s 1954-62 war in Algeria.

In Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts took the concept of surrealism backwards in time, looking at the links between late 19th-century symbolists and the surrealists, long seen as separate movements.

“There was no real rupture between what happened before and after the first world war,” said Francisca Vandepitte, the curator of the Brussels exhibition, which closed in late July. “Our fundamental approach is trying to show, for the first time, the links,” she said, citing Fernand Khnopff’s austere, somewhat unsettling late 19th-century portrait of his sister as an influence on Magritte’s 1932 work The Unexpected Answer, which shows a person-sized hole in a similarly sterile-looking doorway.

Related: Keeping it surreal: my Dalí-inspired art trip to Catalonia

Many of the works that were on display in Brussels are going to Paris, although the show will continue to evolve as it tours. The Royal Museum of Fine Arts is lending one of the jewels of its collection to Paris: René Magritte’s The Dominion of Light, where a clear blue sky filled with white fluffy clouds frames a row of trees and houses shrouded in nocturnal light. “If only the sun could shine tonight,” went a 1923 Breton poem that Magritte quoted.

But “it is not the classic travelling exhibition”, said Vandepitte. Instead, similar themes will emerge in some, but not of all the museums, themes suggested by Breton’s manifesto: dreams and nightmares, night, forests, the cosmos. “Each partner puts on the exhibition, building on the richness of its own collections and heritage,” she said.

After Paris, the exhibition moves to the Fundacíon Mapfre in Madrid, which will turn the spotlight on surrealists from the Iberian peninsula, such as Dalí and Joan Miró. Then it is on to the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which will explore the heritage of German romanticism, before arriving at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in late 2025 to tell the story of surrealists in the Americas during their second world war exile.

Fleeing the Nazi advance, artists came to the US, Mexico and the Caribbean, where they encountered new influences. In Mexico, for instance, surrealists discovered traditional mythologies about volcanoes, “wonderful fodder for the surrealist mindset”, says Matthew Affron, the curator of the Philadelphia exhibition.

“Someone who sees all five versions [of the exhibition] is going to have a wonderfully varied and broad understanding both of the character of surrealist art, in terms of its themes and styles, [and] its main concerns,” he said.

Perhaps the changing nature of the exhibition is particularly well suited to surrealism in all its strange and transgressive variety. “There is no such thing as surrealist style,” Affron said. “I would say it’s really a philosophy of life, almost, and a mindset. One of the key ideas of surrealism is that we must let the imagination be freed to take us to places that we have not yet been.”

Surrealism is at the Pompidou Centre in Paris from 4 September to 13 January

One hundred years ago, in a tiny studio flat in a bohemian district of Paris, a former medical student turned writer set out to define surrealism “for once and for all”. In his Manifesto of Surrealism André Breton called for a new kind of art and literature fired by the unconscious, “the dictation of thought free from any control by reason, exempt from aesthetic or moral preoccupation”.

Far from settling surrealism “for once and for all”, the handwritten document was a departure point for a sprawling, subversive movement of bad dreams, haunting landscapes, fantastical alien creatures, unsettling portraits and visual tricks. Now, a century later, a major exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, opening in September, will celebrate how surrealism spread around the world, far beyond the environs of the French capital.

The Paris exhibition is the second in a sequence of five. The show opened in Brussels and will move on to Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia in 2025. Organisers say it is an unprecedented way to organise an exhibition: while some works and themes remain constant in each city, others change and each museum tells its own story.

Perfect, then, for a movement that always aimed to subvert traditional artistic norms.

When the Pompidou Centre last held a major exhibition on surrealism in 2002, it was characterised as an essentially European movement emanating from a group in Paris. Since then, a great deal of research by universities and museums has enlarged that view, said Marie Sarré, the curator of the show at the Pompidou Centre, the organisation that initiated the project. “This exhibition, on the centenary, aims to show surrealism in all its diversity,” she said.

“It is important to remember that surrealism was a movement that spread – and this is exceptional for an avant-garde movement – around the world, in Europe, but also the United States, South America, Asia and the Maghreb.”

What unites all these artists is Breton’s call to live by the imagination, she suggests. “There is this attention to the wondrous in everyday life. [Surrealism] wants to provoke, to shock, [to show] the wonderful aspect of everyday life that comes from consciousness or access to dreams.”

At the heart of the exhibition will be Breton’s first manifesto, with pages of the original manuscript on display, in a loan from the French national library, which acquired the document in 2021 after it was declared a national treasure.

The emblematic names of the surrealist movement will be present, with works by René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. But visitors will find less well-known figures, such as Japanese artist Tatsuo Ikeda, whose art evoked the horrors of war and the toxic consequences of Japan’s postwar reindustrialisation, and Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican painter active in the middle of the 20th century, who is credited with fusing modernism with pre-Columbian motifs in vividly coloured works.

Reflecting a growing tendency, the Pompidou Centre restores to view neglected female artists, who were long reduced to girlfriends and muses with colourful bit parts in the surrealist story, rather than complex creatives in their own right, such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothy Tanning and Dora Maar.

And it will show surrealism’s contemporary resonances, suggests Marré, citing the surrealist preoccupation with the forest as an echo of modern environmentalism. Surrealism’s anticolonial messages also feature – the Paris exhibition includes artists’ tracts against France’s 1954-62 war in Algeria.

In Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts took the concept of surrealism backwards in time, looking at the links between late 19th-century symbolists and the surrealists, long seen as separate movements.

“There was no real rupture between what happened before and after the first world war,” said Francisca Vandepitte, the curator of the Brussels exhibition, which closed in late July. “Our fundamental approach is trying to show, for the first time, the links,” she said, citing Fernand Khnopff’s austere, somewhat unsettling late 19th-century portrait of his sister as an influence on Magritte’s 1932 work The Unexpected Answer, which shows a person-sized hole in a similarly sterile-looking doorway.

Related: Keeping it surreal: my Dalí-inspired art trip to Catalonia

Many of the works that were on display in Brussels are going to Paris, although the show will continue to evolve as it tours. The Royal Museum of Fine Arts is lending one of the jewels of its collection to Paris: René Magritte’s The Dominion of Light, where a clear blue sky filled with white fluffy clouds frames a row of trees and houses shrouded in nocturnal light. “If only the sun could shine tonight,” went a 1923 Breton poem that Magritte quoted.

But “it is not the classic travelling exhibition”, said Vandepitte. Instead, similar themes will emerge in some, but not of all the museums, themes suggested by Breton’s manifesto: dreams and nightmares, night, forests, the cosmos. “Each partner puts on the exhibition, building on the richness of its own collections and heritage,” she said.

After Paris, the exhibition moves to the Fundacíon Mapfre in Madrid, which will turn the spotlight on surrealists from the Iberian peninsula, such as Dalí and Joan Miró. Then it is on to the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which will explore the heritage of German romanticism, before arriving at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in late 2025 to tell the story of surrealists in the Americas during their second world war exile.

Fleeing the Nazi advance, artists came to the US, Mexico and the Caribbean, where they encountered new influences. In Mexico, for instance, surrealists discovered traditional mythologies about volcanoes, “wonderful fodder for the surrealist mindset”, says Matthew Affron, the curator of the Philadelphia exhibition.

“Someone who sees all five versions [of the exhibition] is going to have a wonderfully varied and broad understanding both of the character of surrealist art, in terms of its themes and styles, [and] its main concerns,” he said.

Perhaps the changing nature of the exhibition is particularly well suited to surrealism in all its strange and transgressive variety. “There is no such thing as surrealist style,” Affron said. “I would say it’s really a philosophy of life, almost, and a mindset. One of the key ideas of surrealism is that we must let the imagination be freed to take us to places that we have not yet been.”

Surrealism is at the Pompidou Centre in Paris from 4 September to 13 January

Friday, February 14, 2020

The Pope of Surrealism himself—an informative, intelligent, readable study

https://www.nytimes.com/1971/05/30/archives/andre-breton-magus-of-surrealism-by-anna-balakian-illustrated-289.html

By Leo Bersani

May 30, 1971

Our favorite intellectual game is to announce revolutions of consciousness. From Charles Reich's parlor game theory of consciousness‐on‐the move to the cataclysmic view of history implied in Michel Foucault's brilliant “Words and Things,” con temporary thinkers have been generously satisfying the appetite for conclusive endings and wholly fresh beginnings which, as Frank Kermode has argued, characterizes Western attempts to impose design and purpose on experience. As it becomes more and more difficult to imagine solutions—for the self and for society—which are not merely repeti tions of the problems they are meant to solve, modes of magical thought help to smother our painful sense of historical entrapment. Apocalyptic thinking provides a glamorous fiction of escape from inescapable history.

To return to surrealism now is a little like looking at ourselves from a distance. Surrealism was the most spectacular announcement in our century of a revolution both psychic and social, and it is no accident that the slogans and manifestoes of May, 1968, in Paris were more reminiscent of surrealist verbal fireworks than of the more austere dialectical re flections on revolution and rebellion of either Sartre or Camus. Contem porary recipes for revolution often blend attacks against capitalism and nationalism, psychic trips designed to expand consciousness, the deter mination to free women from their economic and psychological enslave ment to the “bourgeois rationalism” of a male‐dominated society, and an interest in the occult, in mysterious, correspondences between personal destiny and objective forces or laws. These ingredients, so familiar to us today, were also the principal ele ments of a surrealist program in which the exploration of dreams, the reading of Tarot cards and a battle against economic oppression often seemed to have equal dignity in an enterprise of total human liberation.

For all its “relevance,” surrealism has been rather neglected in Amer ica. Anna Balekian's new book is therefore particularly welcome. Miss Balakian, professor of French and comparative literature at New York University, has written an informative, intelligent and commendably readable study about the Pope of Surrealism himself— its uncompro mising, often tyrannical director and most articulate spokesman, André Breton. Miss Balakian surveys both the life and the work, with a strong emphasis on the exposition of Bre ton's thought. Her point of view is almost unreservedly sympathetic, and while I would myself have been in clined totake a more critical per spective on both Breton's personality and his achievements, Miss Balak ian's judicious book bath documents her own admiration and gives us the evidence for a somewhat less sym pathetic appraisal.

Surrealism as a movement had its ups and dawns, but from 1919—the year of “Les Champs Magnétiques,” the experiment in automatic writing which Breton called the first surreal ist text—to Breton's death in 1966, the continuity of surrealism was guaranteed by the leader's active faith. Through all the defections and the heresies, the Church was always alive in his person. Even after World War II, when the fortunes of sur realism were particularly low, Bret on's apartment in Paris once again became the central office for surreal ist research. And among the recent recruits or admirers were some of the major figures in contemporary French writing: Yves Bonnefoy, Julien Gracq, Malcolm de Chazal, and André Pievre de Mandiargues. Breton could add these names to the extraordinarily impressive list of writers and painters who had already been attracted, however briefly, to surrealism. To mention just a few of these artists—Paul Eluard, René Char, René Magritte, Giorgio di Chirico, Max Ernst—is to recognize at once the unique importance of surrealism in twentieth‐century cul tural life. It was the most powerful magnet for artistic genius in our century. And the magnetizing power of surrealism—its ability to draw so much original talent into its field— is, as Miss Balakian rightly suggests, inseparable from the intellectual and moral authority of its charismatic leader.

Breton had always emphasized the collective nature of the surrealist adventure. Indeed, the originality of surrealism as an artistic movement lies partly in its effort to erase the traditional hierarchy of individual talents which helps us to give a ebherent shape to literary history. Nevertheless, it is of course difficult to avoid a certain violation of the surrealist spirit and to refrain from any assessment of Breton's own literary achievement. Miss Balakian proposes a useful division of Breton's writings into what she calls three distinct structures: “free verse...; logical prose, which is the structure under which can be classified all his critical writings, philosophical essays, and manifestoes and addresses; and finally — perhaps his most original farm—analogical prase, which unlike the prose poem takes on vast propor tions, and often the dimensions of a short novel.”

I have never felt comfortable with the heavy, frequently pompous elo quence of Breton's “logical prose” (especially in the manifestoes). On the other hand, I think Miss Balakian is right to suggest that Breton has been underestimated as a poet. She argues convincingly for his verse, while recognizing its difficulties. We may be put off by the longwinded and harsh‐sounding lines of Breton's poetry, the archaic verb structures, the scientific terminology and occult ist imagery; but at its best his verse has a startlingly fresh shock quality. Still, Breton's particular literary gifts are perhaps most evident in the “analogical prose,” especially in “Nadja” (published in 1928 and avail able in an English translation by Richard Howard) and in “Arcane 17” (written in 1944 and 1947). The dif ferences between these two texts are considerable. If, as Michel Beau jour has written, all of Breton's other works can be thought of as “only fragments” of the triumphant syn thesis of his thought achieved in “Arcane 17,” “Nadja” is perhaps the more appealingly tentative quest of the younger Breton — through his meetings in Paris with the mysterious Nadja—for signs and signals of his own identity. But in spite of differ ences, both “Nadja” and “Arcane 17” illustrate Breton's talent for narra tives in which richly criss crossing networks of anal ogy provide a unified structure saved from rigidity by the unpredictable, open‐ended na ture of the mental processes of association.

Breton was, then, a signifi cant literary figure in his own right, as well as the leader of a movement which func tioned as a major source of inspiration for twentieth ‐ cen tury poetry and painting. Even Sartre, in his famous attack in 1947 on surrealism's view of itself as a revolutionary move ment, conceded that it was “the only poetic movement of the first half of the twentieth century.” But to take Breton and surrealism seriously, we must dismiss—or at least sus pend—our appreciation of its importance in the arts, and consider the surrealist art prod uct as an almost negligible by product in a collective experi ment designed to transform radically the self and society. Surrealism in the libraries and in the museums is the defeat of its revolutionary ambitions — another victory, as we would say, for “repressive tolerance.”

What did surrealism propose in the way of psychic and so cial transformations? Breton wished, as Miss Balakian puts it, “to see how far objective necessity could be made to coincide with the desires of the human will.” The im portance of this lies in an attempted revision of Freudian ideas about the relation be tween desires, dreams or fan tasies and a reality apparently distinct from those fantasies. Breton was interested not in how we adjust our desires to a reality incompatible with them, but rather in the as yet unexplored ways in which the desires expressed in dreams, for example, seek to be satis fied in our waking life. De sire, as he writes in “Les Vases Communicants,” pursues in the external world the objects nec essary for its own fulfillment. The surrealist's availability to chance is not simply a passive stance. The discovery of our techniques for coercing people and things into a conformity with desires we may not even be consciously aware of re quires that state of mind which the surrealists brought to their tireless walks through Paris: a leisurely but attentive observa tion of those movements by which we attempt to make physical space coincide with psychic space. The surrealist stroll is part of a scientific investigation into the mind's power to change the world.

But the “marvelous” coin cidences which Breton records in “Les Vases Communicants” and in “Nadja” leave the larger social world intact. The com plex and at times stormy his tory of surrealism's relation with Communism expresses the group's understandable but no less telling failure to imagine specific ways in which the psychic and the social revolu tions might be coordinated. Aragon abandoned the psychic laboratory for the party. Breton, after a brief period in the party, resolutely returned to more pri vate revolutionary programs.

In discussing this aspect of surrealism, Miss Balakian al lows her sympathy for Breton to silence her critical intelli gence. She assures us that Breton refused to write a paper for the party on the conditions of Italian workers “not due to any dislike of Italian workers but because it jarred with the basic principles of autonomy he maintained in politics as in private life.” The fact that “Breton had not taken orders from anybody since the day he left his father's house” may make us think of him as a very lucky man, but it is hardly an argument for his refusing to take orders. Also, it's clear enough that the assignment “jarred” with Breton's “basic principles of autonomy,” but this intransigent commitment to his own autonomy led to decisions (not to fight with his friends on the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War, not to join the Resistance in France but to spend the war years in America) which make revolu tionary personal freedom look suspiciously dike social quietism (as Sartre called it) if not po litical conservatism. The sur realists were for a time after World War I the bad boys of French cultural life, but to shock the bourgeoisie is not to destroy the structures of bour geois society.

Finally, there was a certain authoritarianism and even in tolerance in Breton's personal ity. His psychological and moral openness had definite limits. I'm thinking of Breton's pen chant for excommunicating “fal len” members of the group, of his exclusion of homosexuals from the surrealist coterie, of his dismissal of Artaud large ly because of the latter's use of drugs, and of the curious discrepancy in Breton's writ ing between the stated desire to explode the traditional bound aries of consciousness and a style that imprisons thought in a tightly disciplined rhetorical art reminiscent of Chateaubri and.

As I have suggested, the vi sion of revolutionary transfor mations of consciousness is per haps a fantasy of escape from history rather than a viable in spiration for programs of his torical change. In Breton's case, that fantasy expressed, in part, an admirably generous view of human possibilities. But —and the example is an in structive one for us—the lan guage of intransigence also helped to protect his somewhat self‐limiting freedom, his re luctance to take the psycho logical and moral risks of a possibly more authentic rebel lion. ■

https://www.nytimes.com/1971/05/30/archives/andre-breton-magus-of-surrealism-by-anna-balakian-illustrated-289.html

By Leo Bersani

May 30, 1971

Our favorite intellectual game is to announce revolutions of consciousness. From Charles Reich's parlor game theory of consciousness‐on‐the move to the cataclysmic view of history implied in Michel Foucault's brilliant “Words and Things,” con temporary thinkers have been generously satisfying the appetite for conclusive endings and wholly fresh beginnings which, as Frank Kermode has argued, characterizes Western attempts to impose design and purpose on experience. As it becomes more and more difficult to imagine solutions—for the self and for society—which are not merely repeti tions of the problems they are meant to solve, modes of magical thought help to smother our painful sense of historical entrapment. Apocalyptic thinking provides a glamorous fiction of escape from inescapable history.

To return to surrealism now is a little like looking at ourselves from a distance. Surrealism was the most spectacular announcement in our century of a revolution both psychic and social, and it is no accident that the slogans and manifestoes of May, 1968, in Paris were more reminiscent of surrealist verbal fireworks than of the more austere dialectical re flections on revolution and rebellion of either Sartre or Camus. Contem porary recipes for revolution often blend attacks against capitalism and nationalism, psychic trips designed to expand consciousness, the deter mination to free women from their economic and psychological enslave ment to the “bourgeois rationalism” of a male‐dominated society, and an interest in the occult, in mysterious, correspondences between personal destiny and objective forces or laws. These ingredients, so familiar to us today, were also the principal ele ments of a surrealist program in which the exploration of dreams, the reading of Tarot cards and a battle against economic oppression often seemed to have equal dignity in an enterprise of total human liberation.

For all its “relevance,” surrealism has been rather neglected in Amer ica. Anna Balekian's new book is therefore particularly welcome. Miss Balakian, professor of French and comparative literature at New York University, has written an informative, intelligent and commendably readable study about the Pope of Surrealism himself— its uncompro mising, often tyrannical director and most articulate spokesman, André Breton. Miss Balakian surveys both the life and the work, with a strong emphasis on the exposition of Bre ton's thought. Her point of view is almost unreservedly sympathetic, and while I would myself have been in clined totake a more critical per spective on both Breton's personality and his achievements, Miss Balak ian's judicious book bath documents her own admiration and gives us the evidence for a somewhat less sym pathetic appraisal.

Surrealism as a movement had its ups and dawns, but from 1919—the year of “Les Champs Magnétiques,” the experiment in automatic writing which Breton called the first surreal ist text—to Breton's death in 1966, the continuity of surrealism was guaranteed by the leader's active faith. Through all the defections and the heresies, the Church was always alive in his person. Even after World War II, when the fortunes of sur realism were particularly low, Bret on's apartment in Paris once again became the central office for surreal ist research. And among the recent recruits or admirers were some of the major figures in contemporary French writing: Yves Bonnefoy, Julien Gracq, Malcolm de Chazal, and André Pievre de Mandiargues. Breton could add these names to the extraordinarily impressive list of writers and painters who had already been attracted, however briefly, to surrealism. To mention just a few of these artists—Paul Eluard, René Char, René Magritte, Giorgio di Chirico, Max Ernst—is to recognize at once the unique importance of surrealism in twentieth‐century cul tural life. It was the most powerful magnet for artistic genius in our century. And the magnetizing power of surrealism—its ability to draw so much original talent into its field— is, as Miss Balakian rightly suggests, inseparable from the intellectual and moral authority of its charismatic leader.

Breton had always emphasized the collective nature of the surrealist adventure. Indeed, the originality of surrealism as an artistic movement lies partly in its effort to erase the traditional hierarchy of individual talents which helps us to give a ebherent shape to literary history. Nevertheless, it is of course difficult to avoid a certain violation of the surrealist spirit and to refrain from any assessment of Breton's own literary achievement. Miss Balakian proposes a useful division of Breton's writings into what she calls three distinct structures: “free verse...; logical prose, which is the structure under which can be classified all his critical writings, philosophical essays, and manifestoes and addresses; and finally — perhaps his most original farm—analogical prase, which unlike the prose poem takes on vast propor tions, and often the dimensions of a short novel.”