Indigenous creators are clashing with YouTube’s and Instagram’s sensitive content bans

Deep in the heartlands of Brazil, Indigenous creators are having to censor themselves to avoid getting banned on social platforms.

Ruwangi Amarasinghe for Rest of World

By GABRIEL DAROS

21 AUGUST 2024 • SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL

Indigenous creators are trying to preserve their cultures and raise awareness through social media.

Instagram and YouTube offer Indigenous creators a way to make money — but have taken down their work for “sensitive content,” including nudity.

●

Xingu

The Kalapalo tribe lives in the Xingu reservation of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.

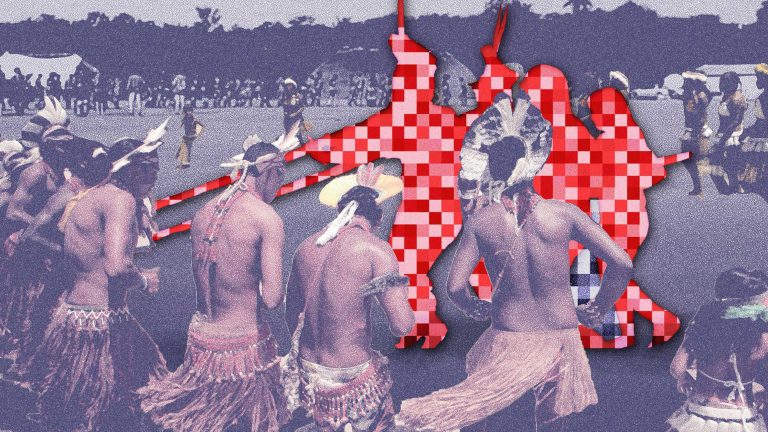

The Kalapalo tribe lives in the Xingu reservation of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.Shortly after Diamantha Aweti Kalapalo posted a video of a funeral ceremony in her village on YouTube in 2016, the platform took it down for violating its policy on child safety, which includes the prohibition of sexually explicit content.

In the video, a couple of tribesmen marched across a dirt road in Xingu, in the wild heartlands of central-west Brazil, playing long ceremonial flutes. Two raven-haired women trailed them, wearing their traditional outfit: a necklace and loincloth.

Such takedowns have become par for the course for Brazilian Indigenous content creators like Kalapalo who have taken to social media in recent years to increase awareness about their cultures and gain a kind of financial independence. Censorship from social media platforms has forced them to sanitize their content, eliciting concern among academics who believe that doing so erodes their archival records.

The internet is important to Indigenous communities “because [theirs] is a culture of orality, of images,” Maria Perpétua Domingues, a history researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, told Rest of World.

She added that these Indigenous influencers are creating a new form of ethno-media — content that both portrays and preserves aspects of their culture without going through the lens of outside actors.

“It is not journalism, it is not all about ‘news,’ it’s everything: music, textures, body art,” said Domingues.

YouTube and Kwai — a popular video platform in Brazil — did not respond to questions from Rest of World, while Meta declined to comment. TikTok declined to comment on a specific example of a video it took down.

Diamantha Kalapalo’s inspiration resides close to home: her older sister, Ysani Kalapalo, who has been recording and uploading videos since at least 2012. Ysani told Rest of World that she started making YouTube videos after she faced “harassment” and “bullying” from nonindigenous neighbors when the family moved to São Carlos, a city nearly 1,375 kilometers away from Xingu, in 2007. She wanted to use social media as a way to expose discrimination.

Ysani returned to Xingu five years later and now has around 2.1 million followers across YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram.

But as she found popularity online, her content slowly shifted.

Ysani Kalapalo’s YouTube page, where she posts videos of her Indigenous community, has over 810,000 subscribers.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGCwxz5GFso

Ysani Kalapalo’s YouTube page, where she posts videos of her Indigenous community, has over 810,000 subscribers.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGCwxz5GFsoHer earlier videos, which highlighted prejudice and the inefficiency of public institutions in supporting Indigenous rights, gave way to less politically charged posts about local cuisine, fire-starting techniques, and traditional dances. Ysani said she had to tone even these down, in large part due to the frequent bans.

Both Kalapalo sisters have had videos taken down from YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Kwai for violating rules related to copyright laws and age-restricted content.

The sisters now ensure that anyone shown in their films is clothed. They also limit some of their content to short Q&A vlogs, which show little other than their faces. While this usually avoids pushback from platforms, it also hinders their effort to preserve their culture, with traditional dances and rites left out to avoid further takedowns.

“People ask me, ‘Ysani, make videos on the rituals or the dances,’ and I can’t,” said Ysani, who believes her YouTube channel is one flagged video away from being banned.

A screenshot from Diamantha Aweti Kalapalo’s removed YouTube video, showing a funeral ceremony in her community. Diamantha Aweti Kalapalo

Diamantha told Rest of World that despite these challenges, “I always try to talk about things that still exist within our culture, things that people aren’t brave enough to voice out.” She often addresses subjects that remain taboo within her community, including issues like domestic violence, infanticide, child marriage, and abuse.

Chirley Pankara, a doctor in anthropology at the University of São Paulo and an Indigenous activist, said that the platforms’ posture on nudity, when not taking these cultures into consideration, results in inadvertent forms of censorship and prejudice.

“We have to safeguard our own culture,” Pankara told Rest of World. “If we take our clothes off when in our communities, then it has to be shown in the same way on the internet.”

The money the Kalapalo sisters make through social media makes up the majority of their earnings, which also come from selling native artisanal goods and giving guided tours of the region.

Pushback against their content isn’t just external. Some members of their tribe have criticized their videos because they mark a departure from the cultural expectation placed on women to keep their thoughts and opinions to themselves, Diamantha said. The sisters said they have received threats on the internet and had spells cast on them by neighbors.

Large online communities have made it possible for some Indigenous creators to pursue ambitious dreams. In February 2024, Ysani published her first novel, titled Itaõ-Kuengü’s Awakening — The Saga of Djamuhu and Ana Sophia, kickstarting her literary career. Meanwhile, Diamantha is hoping to ink a TV deal.

“We dream about our history turning up in some sort of series,” she said.

Gabriel Daros is a journalist and photographer based in São Paulo, Brazil.

Diamantha told Rest of World that despite these challenges, “I always try to talk about things that still exist within our culture, things that people aren’t brave enough to voice out.” She often addresses subjects that remain taboo within her community, including issues like domestic violence, infanticide, child marriage, and abuse.

Chirley Pankara, a doctor in anthropology at the University of São Paulo and an Indigenous activist, said that the platforms’ posture on nudity, when not taking these cultures into consideration, results in inadvertent forms of censorship and prejudice.

“We have to safeguard our own culture,” Pankara told Rest of World. “If we take our clothes off when in our communities, then it has to be shown in the same way on the internet.”

The money the Kalapalo sisters make through social media makes up the majority of their earnings, which also come from selling native artisanal goods and giving guided tours of the region.

Pushback against their content isn’t just external. Some members of their tribe have criticized their videos because they mark a departure from the cultural expectation placed on women to keep their thoughts and opinions to themselves, Diamantha said. The sisters said they have received threats on the internet and had spells cast on them by neighbors.

Large online communities have made it possible for some Indigenous creators to pursue ambitious dreams. In February 2024, Ysani published her first novel, titled Itaõ-Kuengü’s Awakening — The Saga of Djamuhu and Ana Sophia, kickstarting her literary career. Meanwhile, Diamantha is hoping to ink a TV deal.

“We dream about our history turning up in some sort of series,” she said.

Gabriel Daros is a journalist and photographer based in São Paulo, Brazil.

No comments:

Post a Comment