What Does Fascism Look Like? A Brief Introduction

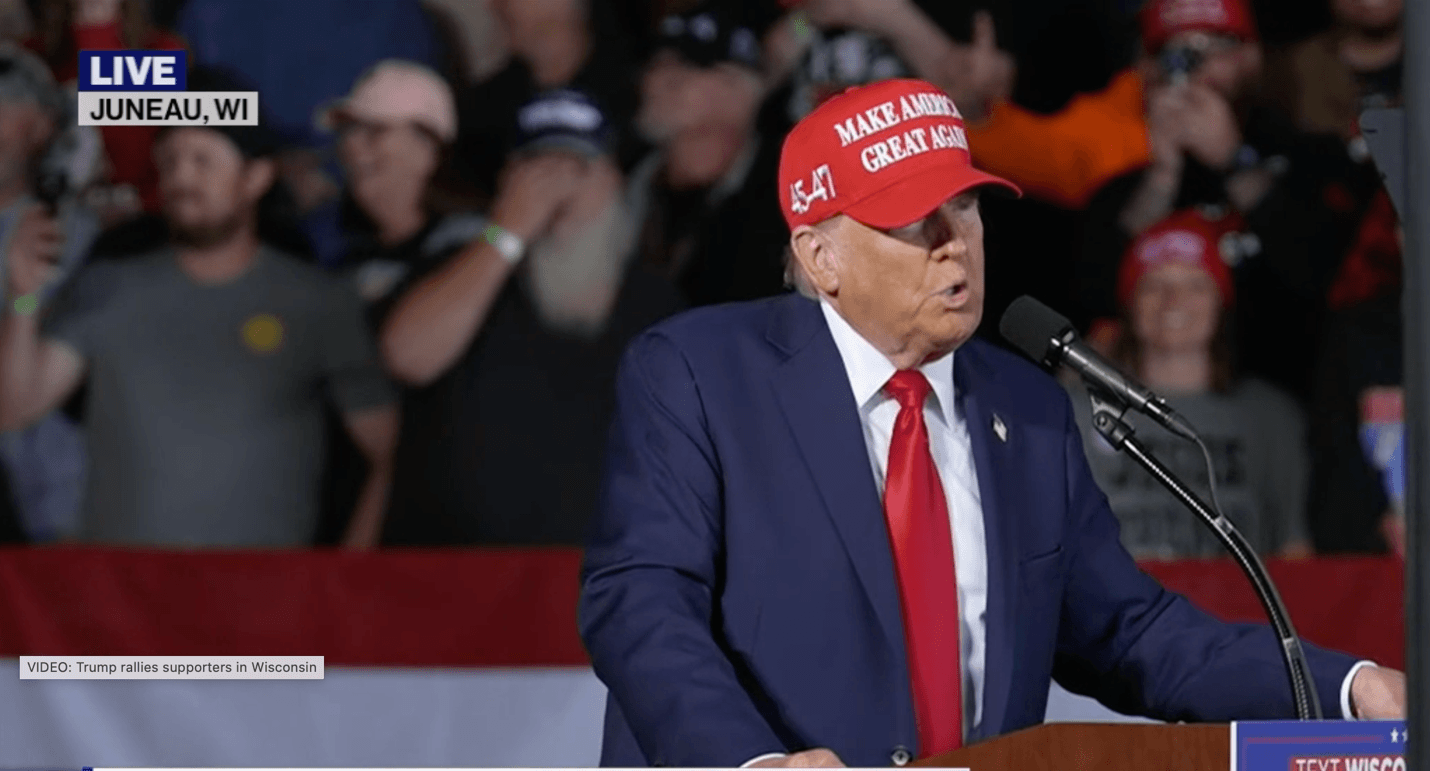

Trump Rally, Juneau, Wisconsin, Oct. 6, 2024. ABC News (Screenshot).

The ideology of fascism

It would be good to be able to recognize fascism when you see it. Sight is our dominant sense (light travels faster than sound) and provides us warning. In addition, because “fascist” is an epithet as well as political term, it must be used carefully. In 1942, a New Hampshire Jehovah’s Witness named Chaplinsky was arrested after calling a Rochester city marshal a “damned fascist.” The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the arrest on the grounds that the expression constituted “fighting words,” excluded from constitutional protection. Recent court decisions in the U.S. have widened speech freedoms, but the word “fascist” remains highly charged, underlining the need for historical and political discretion.

Because of Hitler and Mussolini, it’s relatively easy to recognize fascism retrospectively. Though Hitler preferred the term “National Socialism” and Mussolini “fascism”, their regimes had enough in common that we can use the single word, fascism, to describe them both. They were violent, imperialist, racist, anti-Semitic, anti-individualist, and nationalist. “Palingenetic ultranationalism,” a phrase coined by Roger Griffin in 1991, describes their shared, underlying ideology: interwar fascists believed they were spurring the revolutionary rebirth and modernization of a decadent nation for the benefit of racially superior citizens. Fascism is hierarchical and corporatist; it endorses existing aristocracies of birth and wealth; it is capitalism in its desperate, parasitical phase.

Fascist iconography

While the Germans worshipped ancient Norsemen and Aryans, the Italian fascists venerated the Roman Empire. They embraced its symbols – the fasces (a bundle of sticks with an ax in the middle) and she-wolf. That the legendary founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were suckled by a wolf, allowed the Italian fascists to proclaim their own decent from a fierce and ruthless beast. Like the Roman emperors, Caesar Augustus and Marcus Aurelius, Mussolini and his followers were bent on imperial conquest. Mussolini was Il Duce, the name derived from the Latin dux, or Roman military commander.

The attainment of national and racial destiny, according to the fascist idea, is the result of individual will. Both Italian and German regimes were premised upon the “leadership principle” — in German Führerprinzip — the idea that power and wisdom reside in a single, great leader and that the people owe him loyalty and obedience. In 1936, Hitler and Mussolini quietly agreed to support each other politically and militarily; two years later, they openly formalized the relationship in a “Pact of Steel.” By the Spring of 1945, both were dead – the one by suicide, the other killed by a mob of ordinary Italians.

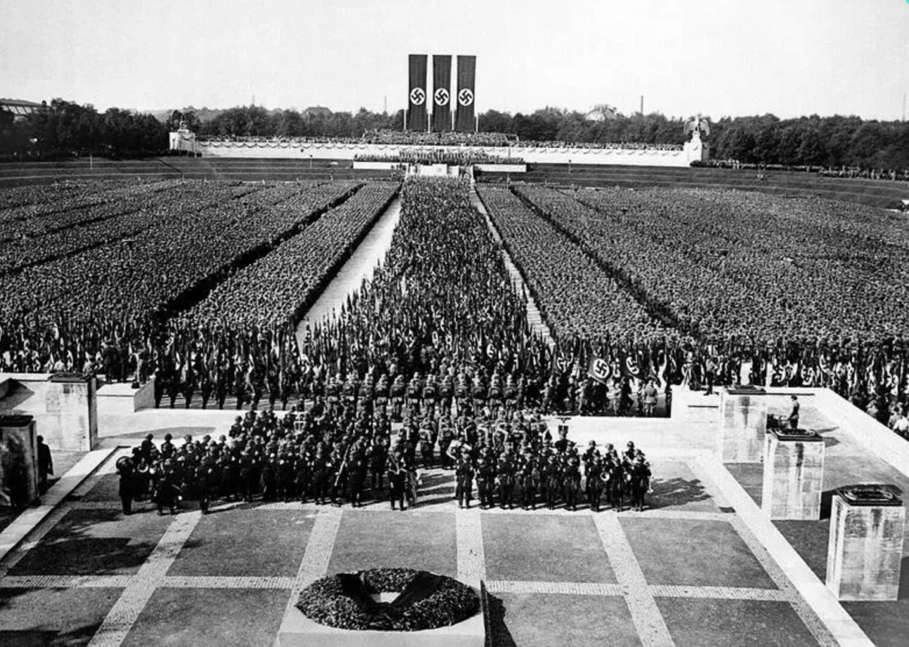

Leni Riefenstahl, Triumph of the Will, 1935.

Because of the indelible stain it left, fascist iconography is memorable: the toothbrush moustache and stiff salute, swastikas, goose-stepping troops, the SS symbol, black shirts, and the ancient fascist emblem itself. Here are two stills from Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary/propaganda film Triumph of the Will, about the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg; And here are two propaganda photos of Mussolini reviewing his troops. Together, they represent militarism, masculinism, elitism, nationalism and the Führerprinzip,

Photographers unknown, Mussolini speaking (Rome, 1940) and Reviewing Troops (Rome, c. 1938).

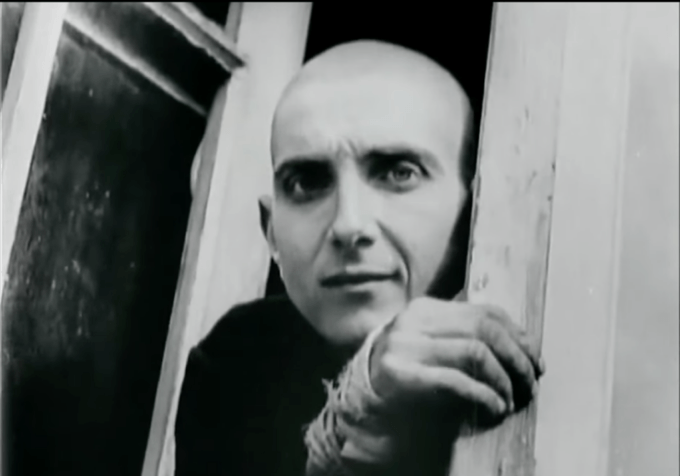

This iconography was so well known that it could be satirized by Charlie Chaplin in his popular, 1940 film, The Great Dictator. The story concerns a Jewish barber (no name given) who bears an uncanny resemblance to the dictator of Tomania, Adenoid Hynkel. Both roles are played by Chaplin. (Rather than Führer, he’s called the “phooey” of Tomania.) Hynkel is allied with, but also in comic competition with Benzio Napaloni, the dictator of Bacteria, played by Jack Oakie.

The movie is vague on the details of Nazi politics and ideology. But the best three minutes of the movie – Hynkel’s ballet with a giant balloon-globe — effectively suggests the imperial ambitions of fascist leaders. It includes many of the icons of Nazism: Hitler’s moustache, uniforms, jackboots, eagle, and swastikas (the latter so well-known they can be changed into doubled x’s). The balloon/globe — which bursts at the end — suggests both Hitler’s violence and self-destructiveness.

Still from The Great Dictator.

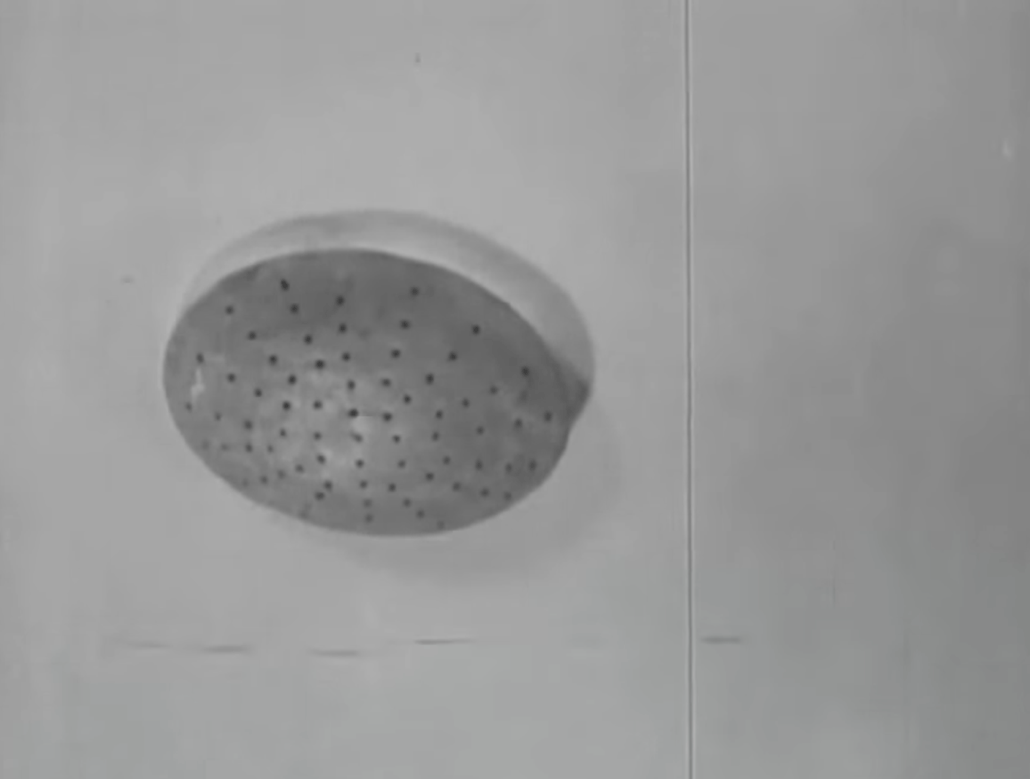

Not until the end of the war, did Chaplin fully learn about another Nazi iconography: piles of emaciated dead bodies, hollow-eyed survivors, showers that sprayed poison gas instead of water, industrial-sized crematoria, and the slogan, Arbeit Macht Frei (“work sets you free”), above the entrance to the forced-labor/death camp at Auschwitz. During the Nuremberg trials (1945-47), documentary films played in court showing these icons of genocide. They were edited and replayed as newsreels all over the world.

From concentration camp films, shown at Nuremberg Trials, Nov. 29, 1945.

Fascist architecture and art in Italy and Germany

If that were all there was to the visuality of fascism, the question in my title would be answered. Look for swastikas, goosesteps, stiff arm salutes, jackboots, or the sign Arbeit Macht Frei, and there you’ll find fascism. But the visual culture of interwar fascism is obviously much more extensive than that, encompassing fine art, architecture, and design. And it’s quite varied — up to a point.

Giuseppe Terragni, Casa del Fascio, Como,1932–36. (Photographer unknown).

During their first decade in power, fascist authorities in Italy allowed a wide variety of artistic and architectural styles to co-exist and even flourish. Avant-garde modernism, with its focus on structure and function, appealed to a state striving to develop or modernize its infrastructure. Many civic buildings, schools and railway stations — such as the Santa Maria Novella (1932-35) by Giovanni Michelucci and others — present an austere, modernist aspect. The archetypal example of fascist modernism however, is Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio, in Como (1932–36). The building, with its planarity, grid, and lack of ornament, draws upon Walter Gropius’s innovations at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, and Gerrit Rietveld’s Schroeder House, among other buildings. Tarragni was part of Gruppo Sette, a coalition of Italian rationalists. In their 1926 manifesto, they rejected Expressionism and Futurism in favor of “logic and rationality.”

Marcello Piacentini, Palace of Justice, in Milan,1932-40. (Photographer unknown).

Mussolini himself in 1933 proclaimed rationalism the correct architectural style for fascist Italy, but internal and external competition forced a change, and by the middle 1930s, a more traditional and ostentatious architecture – an architecture of power — was favored. An example is Marcello Piacentini’s colossal Palace of Justice, in Milan (1932-40). It speaks the language and rhythm of classicism – tripartite horizontal and vertical division of the main facade, rusticated lower level, tripartite central portals, half columns between the windows, plus cornices and entablature. But ornamentation (capitals, fluted columns, pediments and decorative moldings) is reduced or eliminated. Classical antiquity is recalled not by detailing, but sheer monumentality — it has 1200 rooms — and lavish materials, chiefly marble and bronze.

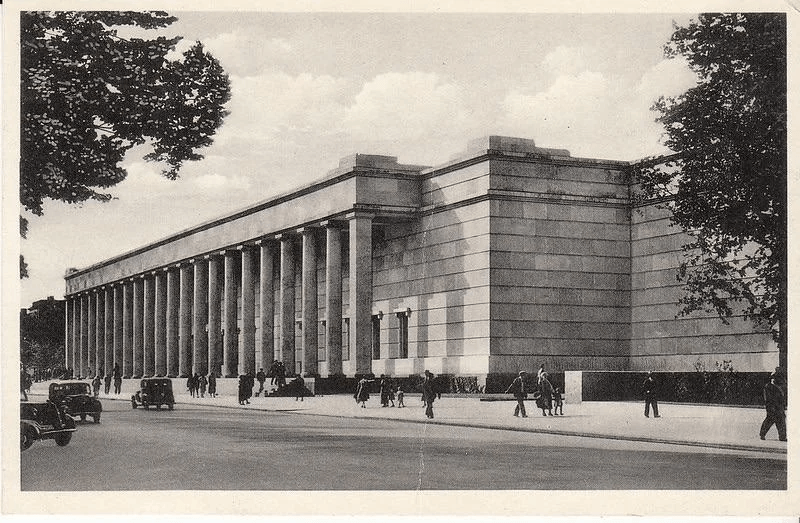

In Nazi Germany, the modern movement in architecture – meaning the Bauhaus and its planning and design offshoots — was cast aside as soon as Hitler came to power in 1933, though no theory or program of art and architecture ever took its place. Instead, modern artists and designers and more traditional ones were forced into competitions which the former could not possibly win. Thus, classicism – at once buffed-up and stripped down –was the chosen idiom for major architectural commissions such as the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich (1936) by Paul Troost, and the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin by Albert Speer (1939).

Postcard of Haus der Deutschen Kunst, Munich, 1936.

Albert Speer, New Reich Chancellery, 1939. (Photographer unknown).

Speer was of course the kingpin of Nazi architecture. He was Hitler’s favorite and later named Minister for Armament and War Production, in which post he commanded hundreds of thousands of slave laborers. Speer claimed to have no architectural program or theory, only a desire to tailor his plans to the Fuhrer’s will. Indeed, his buildings, and Nazi public architecture in general, are not programmatic expressions of Nazi ideas about race, Lebensraum, Judeo-Bolshevism or the Führerprinzip. In both architectural and symbolic terms, they are banal in the extreme. They are however, effective instruments of political strategy, in particular, war planning. Parade grounds, Zeppelin fields, stadiums, party headquarters, the Chancellery and more were built with a speed and scale intended to drum up enthusiasm for war. They were public demonstrations that Germany was a powerful and ambitious nation. Only a state with a legitimate claim on empire would build on such an imperial scale and at such expense. “On the long walk from the entrance to the reception hall,” Hitler said of the Chancellery, “they’ll get a taste of the power and grandeur of the German Reich!” Two over life-sized figures by Arno Breker, Hitler’s favorite sculptor, flank the entrance court; on the left is Partei and on the right, Wehrmacht. They are roughly derived from the famous ancient Greek bronze figure of Zeus, hurling a thunderbolt.

Albert Speer, New Reich Chancellery, grand gallery, 1939. (Photographer unknown.)

Arno Breker, Partei and Wehrmacht, outside, New Reich Chancellery, 1939. (Photographer unknown.)

As in architecture, so in art. There was no single aesthetic criteria guiding Nazi or fascist painting and sculpture, except the consistent preference for traditional over modern art. That, however, was not unusual. Representational art was the preference across Europe, Russa, and the Americas. It could be used for indoctrination, persuasion or entertainment, and was deployed by progressive as well as regressive institutions and states. Despite the inroads of modernism, traditional art retained its popular appeal. It was familiar – available to be seen in churches, newspapers, advertising, and movies – and therefore comforting. The great modernists on the other hand — Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Klee, etc – despite their considerable success, were little understood by the broad public.

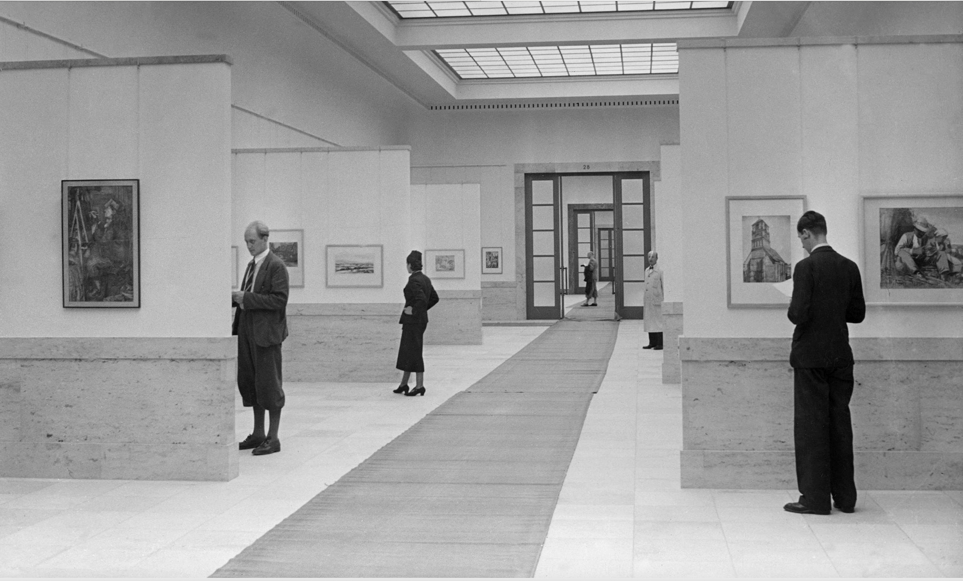

Where fascist or totalitarian states differed from capitalist democracies, was in their enforcement of the preference for traditional art. In Nazi Germany, this was most clearly manifested in the contest between the annual Great German Art Exhibitions, inaugurated in 1937, and the Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937-38. The former arose from an open

Great German Art Exhibition, Haus der Deutschen Kunst, 1937 (photographer unknown).

Catalogue for Great German Art Exhibition, 1937; Adolf Ziegler, The Four Elements, 1934.

invitation to artists in 1937 to submit works for national exhibition at the new, Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich. After seeing the submissions, which included some modern and expressionist works, Hitler was furious. A few years before, he had called modern artists “incompetents, cheats and madmen.” He thereupon fired the jurors (who had been chosen by propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels) and appointed his personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffman to curate the selection. In addition, he endorsed

Visitor at Degenerate Art exhibition, Munich, 1937.

Goebbels’ proposal to mount a didactic exhibition of the rejected artists and many others, under the rubric “Entartete Kunst”. The “degenerate artists” included much-derided German expressionists such as Grosz, Dix, Kirchner, Marc, and Nolde, as well as dozens of others, including Impressionists, Post-Impressionists (including Van Gogh), Cubists, Dadaists, Surrealists and more. The works were hung helter-skelter among wall texts that read, for example: “nature, as seen by sick minds”, “madness becomes method”, “revelation of the Jewish racial soul” and “deliberate sabotage of national defense” (the latter displayed anti-war imagery by Dix, Grosz and others). And while the Great German exhibition was lauded in the Nazi-controlled press and the Degenerate exhibition mocked, the former was little visited while the latter attracted nearly 3 million total viewers. It was probably the most visited art exhibition of all time. Whether that represents widespread embrace of the Nazi derision of modern art, or broad endorsement of the works is unclear.

Crowd awaiting entry to Degenerate Art exhibition, Berlin 1938 (photographer unknown).

What does fascism look like today?

Fascism doesn’t have a light switch with an on/off setting. It may be found in capitalist democracy, just as democracy may be discovered in the recesses of fascist states. Maybe it’s better to say fascism is controlled by a dimmer switch. Under Donald Trump, turned up quite high. Under Biden it has been dialed down, but still glows in the background and sometimes flares up, like in the current U.S. president’s growing anti-immigrant rhetoric, or his consistent support for Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza and now Lebanon. That’s fascism by proxy.

George Bergstrom, The Pentagon, Arlington, VA, 1941-43.

However, it’s difficult to speak of fascist art and architecture in the U.S. The amount of public patronage of art is tiny, and what exists is extremely diverse in form and style. There are certainly municipal, state and federal buildings that serve deeply oppressive, even fascistic, purposes: prisons, psychiatric hospitals, military bases, and some schools. And a few buildings, like the U.S. Pentagon resemble in monumentality and style, buildings by Speer. (It was built just two years after the completion of The New Reich Chancellery, and may have been influenced by it.) But these are outliers and marked by contradiction. For example, when the Pentagon was completed in between 1943, it was the only public building in the state that had integrated lunchrooms and toilet facilities. In that respect, it may have been the least fascist building in Virginia!

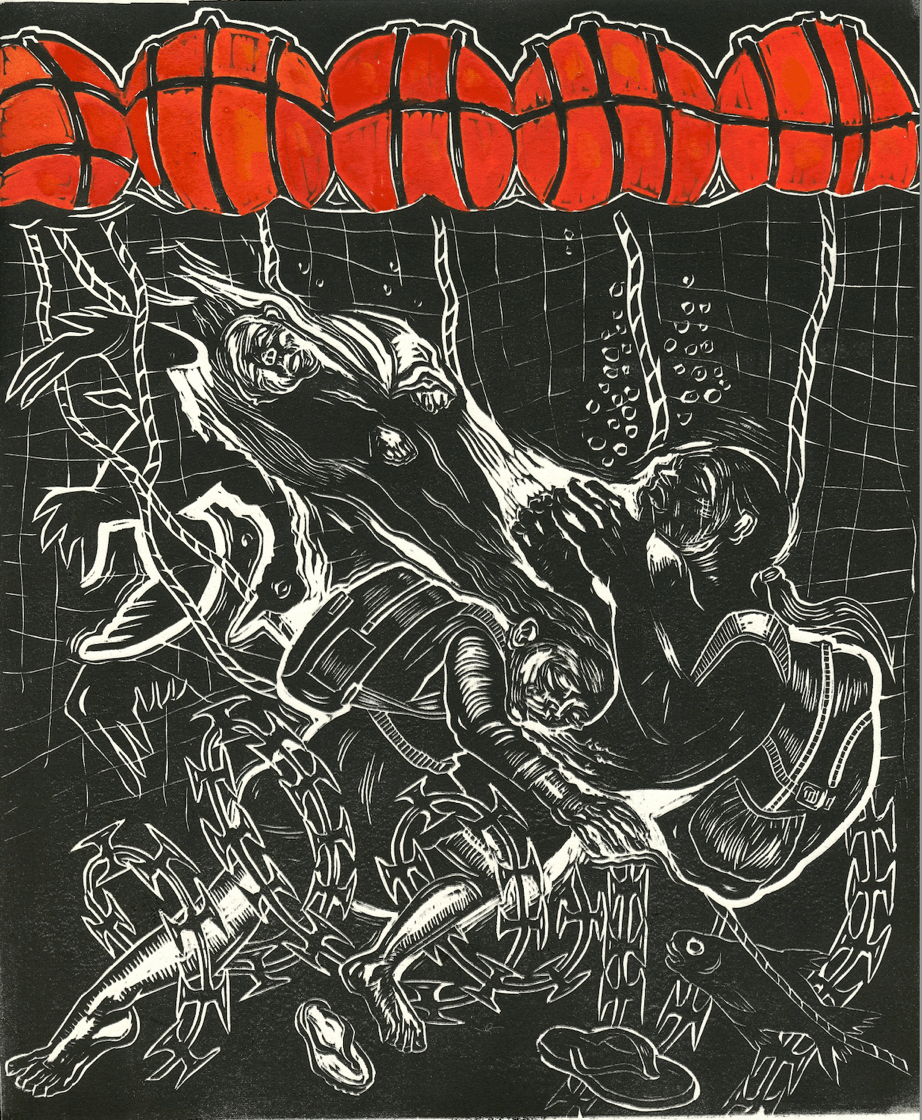

Sue Coe, Rio Grande, 2023. (Courtesy the artist).

Today, the U.S. the border wall with Mexico – actually, dozens of different and colliding walls, fences, and natural barriers – is an icon of fascism. So are the concentration camps (detention centers) that temporarily house immigrants. But the image of these facilities — in photographs and memory — have also made them a resource of anti-fascism, as apparent in drawings and linocuts by British-born, U.S. artist Sue Coe. For example her linocut titled Rio Grande, depicts immigrants caught up in razor wire and drowned on the Texas/Mexico border. This actually happened on Jan. 14, 2023. (For more such images, please see our new book, The Young Person’s Illustrated Guide to American Fascism.)

A more clear-cut diagnostic of fascism is the MAGA hat. Trump often wears one when he gives speeches, and regularly repeats the phrase “make America great again.” Here’s a few lines from a speech he gave in 2023, that has since become standard at rallies: “Illegal immigration is poisoning the blood of our nation. They’re coming from prisons, from mental institutions, from all over the world. Without borders and fair elections, you don’t have a country. Make America great again.”

MAGA is today emblazoned on millions of caps, T-shirts, yard-signs, flags and more, It’s an expression of palingenetic ultranationalism — almost. By proposing the revival of an earlier time, it’s more conservative than revolutionary; and the “greatness” it promises is not imperialist. There is no discussion of “lebensraum”. Indeed, Trump’s other major slogan, “America First” is isolationist, dating back to Charles Lindberg’s America First movement, which aimed to head off U.S. participation in World War II. But given Trump’s rhetoric about Iran and China, as well as his proposals to increase military spending and massively update and expand the nation’s nuclear arsenal, I’d argue that his policies are in fact expansionist – in that sense, fully consonant with fascist militarism and imperialism. Trump’s rallies suggest he has a war strategy. They are intended to mobilize thousands of followers who will, if needed, storm U.S. voting stations, state capitals and the capital in Washington to overturn an unwelcome election outcome.

As we have seen, fascism has no settled or essential iconography. It can’t. Wherever it appears, it draws from motifs and ideologies that are distinctive to that particular nation. In 1939, a Yale professor and Methodist minister named Halford Luccock gave a lecture at Riverside Church in New York City. Observing the growing strength of Nazism and fascism abroad and a rising fascist movement in the U.S., he warned his audience:

“When and if fascism comes to America it will not be labeled ‘made in Germany’; it will not be marked with a swastika; it will not even be called fascism; it will be called, of course, ‘Americanism.’…The high-sounding phrase ‘the American way’ will be used by interested groups, intent on profit, to cover a multitude of sins against the American and Christian tradition, such sins as lawless violence, tear gas and shotguns, denial of civil liberties.”

Huey Long, governor of Louisiana from 1928-32, himself often called a fascist, said: “American Fascism would never emerge as Fascist, but as a 100 percent American movement; it would not duplicate the German method of coming to power but would only have to get the right President and Cabinet.” Fascism, as I said at the beginning of this brief survey, is easy to see in retrospect, but not in prospect. However, when it appears right in front of you, identification becomes simple – signs and symbols appear everywhere. As we approach the U.S. election, we can clearly witness one political party’s tight embrace of fascism – but seeing it doesn’t mean we can easily stop it.

No comments:

Post a Comment