10 Reasons Why ICE is Harassing Native Americans

ICE and Border Patrol are increasingly detaining Native American citizens, and ignoring or refusing to treat Tribal ID cards as proof of citizenship. Just north of where ICE killed Minneapolis rights monitor Renee Nicole Good, agents have detained tribal citizens in the clearly Native neighborhood around Franklin Avenue, where the American Indian Movement was itself born to monitor police brutality. In much the same way, ICE often racially profiles immigrants who have become citizens.

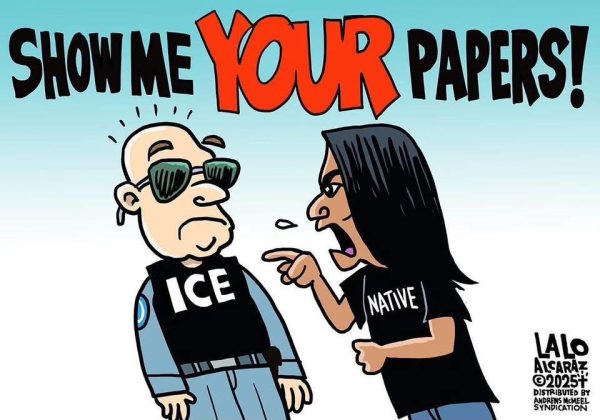

Many tribal leaders are speaking out, accurately pointing out that the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act granted U.S. citizenship to Native peoples, alongside their own tribal citizenship, so ICE has absolutely zero legal basis for stopping any tribal citizen. It might be easy for non-Natives to assume that ICE is simply unaware of tribal citizens’ status, and with proper education and training they will treat Native people as equal citizens, and stop the harassment.

The problem is that ICE already knows full well that Native Americans are citizens.

Even when shown Tribal IDs and passports, many ICE agents have been dismissive or hostile. And unfortunately there’s a reason. The harassment and detention of Native Americans today is the latest episode in a long and deep history of colonizing Indigenous peoples at home and abroad.

Let’s connect the dots, to show why this trend of anti-Native harassment is no accident:

- Many of the immigrants terrorized by ICE are themselves Indigenous, including those from Guatemala and southern Mexico. In 2019, Trump evoked an “invasion” of Central American refugees in “caravans,” and mocked their pleas for asylum. Guatemalans working at the Trump National Golf Club were ridiculed by a supervisor as “donkeys” and “dogs.” Last year, Trump cut funding for Indigenous language translation in immigration enforcement, and sought to deport Guatemalan unaccompanied children. These Indigenous immigrants, many of them fleeing conflicts fueled by the U.S., have borne the brunt of ICE mistreatment.

- Ask the Native nations whose lands were crossed by the U.S.-Mexico border, such as Tohono O’odham and Kumeyaay, how for decades they’ve faced harassment by Border Patrol and ICE (and their predecessor agencies) and constantly forced to prove their citizenship or abandon their relatives south of the border. The militarization of the border and construction of the border wall increasingly cuts them off from family ties, cultural sites and knowledge, and the ability to economically trade and support each other. These tribes (and others bisected by the U.S.-Canada boundary) still face a constant struggle to safely cross the border.

- There’s always been an overlap between anti-Native and anti-immigrant movements, and some politicians and agencies promote both forms of racism. A 2006 ICE raid on meatpacking plants was named “Operation Wagon Train.” When Elaine Willman, founder of the anti-Native Citizens Equal Rights Alliance, was on the Toppenish City Council in central Washington, she could have pitted the local Mexican immigrant population and Yakama tribal members against each other, but she instead accused tribal sovereignty of “contributing to an increase in illegal immigration.”

- Trump has explicitly opposed Native sovereignty, ever since he railed against tribal casino competitors in 1993. Starting in his first term, he used “Pocahontas” as a slur, hung a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office, oil pipelines and drilling on Native lands, slashed environmental regulations and climate funds that protect Native lands, waters, and sacred sites, cut federal programs that benefit tribes, began to take tribes out of trust, and much more. Last year he drastically cut tribal college funding, and his Department of Justice tried to make the preposterous argument that “birthright citizenship” does not apply to Native Americans. Previous administrations have not been friendly to tribal interests, to varying degrees, but Trump has taken it to a higher level, especially in his second term.

- Department of Homeland Security recruitment ads for new ICE agents have blatantly evoked Manifest Destiny images of white supremacy that seemingly have nothing to do with immigration enforcement, including John Gast’s “American Progress” painting as “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth defending.” And just who are these newly recruited agents? Back in 2020, it was common to see armed far-right militiamen threaten anti-Trump and Black Lives Matter marches, but now these paramilitaries are notably absent at even more widespread rallies. Perhaps that’s one reason that so many ICE agents wear masks, so they won’t be unmasked as Proud Boys or Three Percenters.

- Anti-Indigenous theorists have usually equated tribal sovereignty with Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), and posed Native self-determination as “special rights” based on race, rather than on tribes’ political status as nations. But as I noted in a recent post, in the past few years they’re refocusing on the “dangers” of the growing opposition to settler colonialism, whether in Palestine, South Africa, or North America. They’re now concentrating their ire on Indigenous self-determination as a threat to settler states’ entitlement to land, and on Native Studies in education as a threat to the national narrative of progress. The MAGA message is shifting away from race and toward place, and who controls natural resources. And it’s no accident that Trump threatens to annex resource-rich Greenland, just when it’s poised to become the first independent Indigenous state in the Americas. The puzzle begins to fit together.

- The connections between the colonization of Native America and the overseas extension of the American Empire long predate Trump. Western Army forts were the first U.S. military bases on foreign soil. The doctrine of “Manifest Destiny” was the template for the expansion of U.S. colonialism into the Caribbean, Hawai’i and other Pacific nations, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In his classic Facing West: the Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire Building, Richard Drinnon documented that the “Indian Wars,” Philippine-American War, and Vietnam War used identical tactics, and rhetoric of enemy territory as hostile “Indian country.” Drinnon concluded, “In each and every West, place itself was infinitely less important…than what the white settlers brought in their heads and hearts to that particular place. At each magic margin, their metaphysics of Indian-hating underwent a seemingly confirmatory ‘perennial rebirth.’…. All along, the obverse of Indian-hating had been the metaphysics of empire building…. Winning the West amounted to no less than winning the world.” Evoking this history, it’s no accident that the military deploys “Tomahawk” missiles, and helicopters named “Black Hawk,” “Apache,” and “Chinook.”

- In Latin America, the source of most immigration into the U.S., Indigenous-led movements are increasingly being targeted by U.S. military and intelligence agencies in their counterinsurgency planning. The National Intelligence Council projected in 2005 that the “demands of free markets” will “drive indigenous movements, which so far have sought change through democratic means, to consider more drastic means.” The Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, applied this emerging doctrine in Military Review, by lumping together “Insurgencies, Terrorist Groups and Indigenous Movements,” particularly in Mexico. The FMSO’s Lt. Col. Geoffrey Demarest stated in his book Geoproperty that “The coming center of gravity of armed political struggles may be indigenous populations…” and that the Internet is increasingly being used by “Indigenous rebels, feminists, troublemakers…”

- The so-called “Global War on Terror” grew from Iraq and Afghanistan into Pakistan, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia, in the name of combating “Islamist terrorism.” Yet within all these countries, the main targets of the wars have been “tribal regions,” and the frontier language of Indian-fighting is becoming the lexicon of 21st-century counterinsurgency. The “Global War on Terror” has morphed into a “Global War on Tribes” (as I noted in an article with that title). Counterinsurgency doctrine views “tribal regions” as festering cauldrons of “lawlessness” and “breeding grounds” for terrorism, unless the tribes themselves are divided against each other and turned against the empire’s enemies. Robert D. Kaplan brazenly wrote in 2004 that “the American military is back to the days of fighting the Indians,” and it’s no accident that in the 2011 raid that killed Osama Bin Laden, his military codename was “Geronimo.” The “Global War on Tribes” is first and foremost a grab for the many natural resources remaining on Indigenous lands, but also a war against the very existence of “tribal regions” that are not under centralized state control, and still retain collective forms of property and social organization.

- The swings of the domestic Indian policy pendulum have always been tied into foreign and military affairs: the era of allotment and boarding schools with the age of imperial conquests and “English-Only” restrictions, the Indian New Deal with nonintervention abroad, the Termination Era with the Cold War against communism, tribal self-determination with the rise of national liberation movements, and the white backlash against tribal sovereignty with the far-right swing against multicultural societies. In U.S. military interventions at home or abroad, the existence of Indigenous peoples, lands, and lifeways has always been deemed a threat to the colonial order, and Trump’s administration is making that longstanding view more open and transparent with every statement and action. Restricting the rights of Native peoples and dispossessing their lands is the original disease of colonialism, not a side effect.

The fact that ICE and Border Patrol are now harassing and detaining Native citizens is a warning to the larger U.S. society. As federal Indian law scholar Felix Cohen wrote in 1953, “Like the miner’s canary,” U.S. treatment of Native peoples “marks the shift from fresh air to poison gas in our political atmosphere.” Trump began his second term by demonizing Haitians, Somalis, and Venezuelans, and is taking the next step by harassing Native citizens, and will then extend the repression to all citizens. ICE started as a bludgeon against immigrants, but is becoming a test case for expanding authoritarianism against everyone. Only by showing active solidarity with both immigrant and Indigenous communities (and other targeted communities), can we block his plans.

ICE knows that the rights of Native peoples and recent immigrants are connected, and more Americans should learn that too.

Zoltán Grossman is a professor of Geography and Native American and Indigenous Studies at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, and a longtime treaty rights activist. He is a past co-chair of the Indigenous Peoples Specialty Group of the American Association of Geographers. He was author of Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands, and co-editor of Asserting Native Resilience: Pacific Rim Indigenous Nations Face the Climate Crisis. His courses have included “American Frontiers” and “A People’s Geography of American Empire.” His faculty website is here.

No comments:

Post a Comment