Ukraine has lost an entire generation in the four-year war with Russia and, if the conflict continues for another two years, it will lose another one.

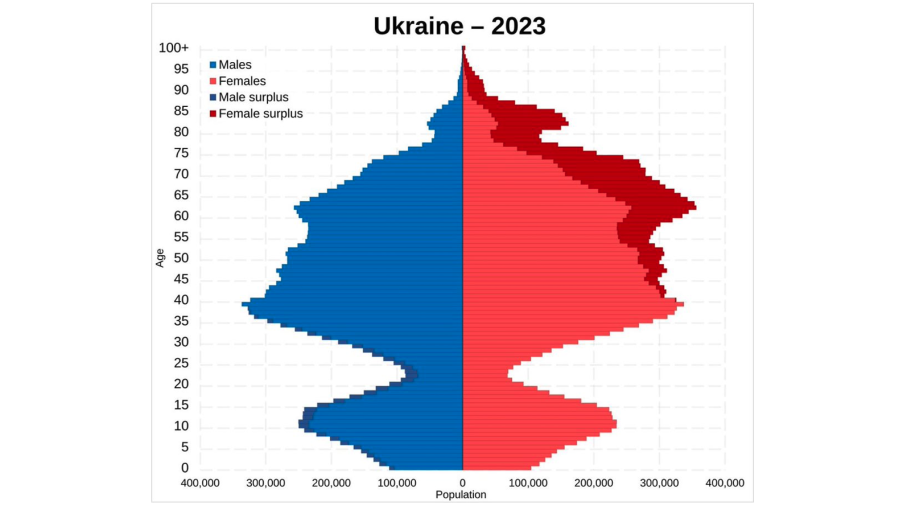

The latest demographic data and international estimates highlight a huge hole that has appeared in Ukraine’s demographic pyramid at 25 years of age. The number of deaths in the war remains a closely guarded state secret, but the horrific losses Ukraine has suffered shows up clearly in the demographic data. Ukraine is in the midst of a long-term population collapse unprecedented in Europe outside wartime.

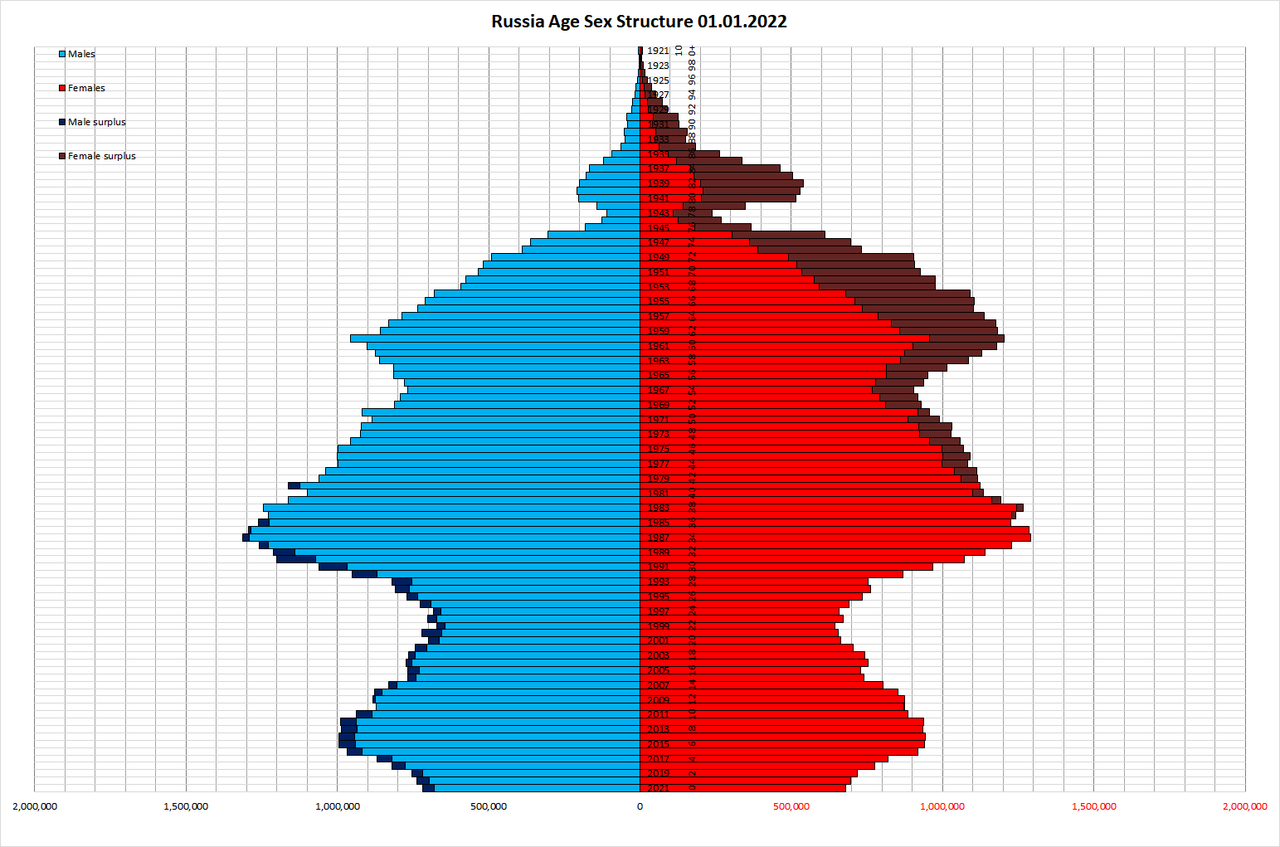

The results are worse than the same demographic dent that appeared in Russia’s demographic pyramid from the chaos of the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union when male life expectancy fell to a mere 56-years-old – but Ukraine’s war induced losses are far worse. A healthy population pyramid should be a triangle.

Russia has also suffered a demogtraphic decline and heavy losses in the younger cohorts, but the dents in its population syramid are not as bad as those Ukraine has suggered.

While Russia is reported losing 1,000 or more men in Donbas a day, whereas Ukraine is maybe losing a fifth of this number, according to scattered and unconfirmed reports, the relative sizes of the two countries’ populations mean that Ukraine is suffering worse than Russia, despite the lower casualty count.

Russia has 1.4mn men under arms, but this only accounts for 1% of its total population. Ukraine has around 850,000 service men, but this accounts for 3.3% of its population. That means Ukraine has to kill three times more Russians to just keep even in the manpower struggle. And Ukraine is already bumping up against the ceiling of its pool of military-aged men despite full mandatory conscription. Russia’s pool of potential servicemen remains much deeper, and it is able to still rely exclusively well-paid volunteers to cover its battlefield losses with an estimated 30,000 fresh recruits a month.

The scale of the crisis is starkly illustrated by Ukraine’s 2023 population pyramid, which shows deep hollows among children, working-age adults and men in their twenties to forties, reflecting a combination of war deaths, mass displacement, plummeting birth rates and persistently high mortality.

As 80% of the estimated 8-11mn refugees that have fled the country since the war began are believed to be women and children. The longer the war goes on, the less likely this group is to return. Women outnumber men sharply in older age groups in the pyramid, while younger cohorts are visibly thinner than those of previous generations.

As bne IntelliNews reported, Ukraine's demographic trajectory now hinges on how many of the millions who fled the country return after the war. Surveys suggest at least a third may not come back, citing security concerns, destroyed housing and better economic prospects elsewhere.

The longer-term outlook is even more severe. United Nations projections cited by IntelliNews show Ukraine’s population could shrink to about 15mn by 2100, down from more than 40mn before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. Even before the war, Ukraine was among the fastest-shrinking countries in the world, as part of a wider demographic crisis that will take Emerging Europe population levels back to the early 20th century. Nowhere in Europe currently has fertility rates over the 2.1 necessary to keep a population’s size stable.

Birth rates have collapsed to historic lows. As bne IntelliNews reported on October 22 that Ukraine’s fertility rate has fallen to its lowest level in 300 years, with wartime uncertainty, economic hardship and family separation discouraging childbearing. At the same time, mortality remains exceptionally high – three-times higher than the birthrate. According to data, Ukraine has both the highest mortality rate and the lowest birth rate globally.

The war has made pre-existing demographic problems far worse that date back decades, including poor public health, widespread emigration and low life expectancy for men. The loss of working-age adults is expected to weigh heavily on Ukraine’s post-war recovery, constraining economic growth, public finances and the ability to sustain pensions and healthcare.

This month the war in Ukraine will have gone on longer than the Soviet Union’s participation in WWII – known in Russia as the Great Patriotic war – that emptied entire cities of men. The textiles centre of Ivanov, a few hundred kilometres south of Moscow, was known as the “city of the widows” in the post-war Soviet Union as so many of its menfolk died fighting the Nazis. Many cities in Ukraine are very likely already in a similar position.

There is a chance that the war will be ended in the coming months. Zelenskiy said this week that he hopes the war will end this summer. However, if the talks fail, the EU has proposed a €90bn loan for Ukraine on December 19 that will prolong the war for another two years. As Ukraine is already suffering from an acute shortage of men, money and materiel, the only way that Bankova can replenish its dwindling fighting force will be by lowering the conscription age from the current 26-years-old to 18-years-old and sacrifice another generation to the killing fields of Donbas.

Even if fighting ends soon, demographers warn that Ukraine faces a narrow window to stabilise its population post-war through refugee returns, reconstruction and support for families. Without that, the country’s demographic curve suggests a future defined by rapid ageing, labour shortages, swelling pension and disability costs, falling tax income revenues and a sharply diminished society.

No comments:

Post a Comment