It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Monday, January 06, 2020

Sanders draws an oversized crowd to talk student debt, minimum wage, Medicare

By Logan Kahler, Managing Editor lkahler@newsrepublican.com

Posted Jan 5, 2020

BOONE — Democratic presidential candidate and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders talked to a packed house of approximately 400 people at the Fareway Conference Center at Cobblestone Inn & Suites Sunday morning, where he said the goals he has for the country are not “unrealistic.”

Sanders was greeted by a roar of applause and responded by taking a moment to note what his hopes are for the country.

“You’re probably wondering, how did we get to where we are and maybe most importantly, where do we want to go?” Sanders said. “I’m here to tell you how we’re going to get there.”

“What makes our campaign different than others for a number of reasons—one is to tell the voters of Iowa, New Hampshire, Vermont to think a little bit outside of the box,” Sanders said. “Our motives may sound untraditional, but they’re certainly not unrealistic.”

During the event which was promoted as being a brunch, an attendee in the crowd took the microphone to profess her struggle with student loan debt as she pursued education to become a veterinarian. Throughout vet school, she had collectively gathered about $360,000 in student loans, the woman said.

Sanders said that when he is elected, he will cancel all the $1.6 trillion student loan debt to all Americans, as well as make universities tuition free.

“We are seeing young people delaying marriage, having children, unable to buy a car or even a house because of outrageous student loan debt,” said Sanders. “Think about it, we need veterinarians, doctors, but they shouldn’t be punished for the rest of their lives because they have an education.”

Sanders said the massive amount of student loan debt could easily be to blame for the weak economy. He said student loan debt is a financial burden not only on the individual but on the country and its economy.”

In an unheard-of comment from Sanders, he stated there was one thing he is happy for from Donald Trump and that’s the economy is actually picking up. There are more jobs now than when Trump became president, Sanders said.

“But just because there are more jobs, doesn’t mean that people can thrive..That’s why we need to raise the minimum wage to $15.”

According to the Bernie Sanders communications team, the event projected to have a crowd of 150, but a final verified count revealed a total of 431 people. For context, 800 people caucused in the city of Boone in 2016.

Many of those in attendance Sunday were drawn to Boone from all over because of their interest in Sanders’ health coverage policy.

Sanders told a story about a woman he met on the campaign trail who had undergone treatments for cancer. Because of the disease, she had to quit her job, lose her insurance, resulting in her death from the inability to pay her hospital bills.

“You see people all over the country putting their lives on hold because something with their health comes up,” Sanders said. “The drug companies have a grip on the costs of life-saving medications that we the American need to survive.”

“And that’s just not right.”

Professionals in the healthcare field have varied opinions on Sanders’ beliefs.

“I really like Bernie because he’s older and more experienced than the other candidates,” said Helen Clark of Ogden. “And he can beat Trump.”

Clark, 61, of Ogden, is a physical therapist who has been in healthcare for 40 years. She traveled to Boone to see Sanders as he is one of her top picks for her vote, second to former Vice President Joe Biden.

After listening to his platform on universal health coverage, Clark said it made more sense to her.

“Being in healthcare for 40 years, I can see how the lack of healthcare can make an impact on people,” Clark said. “I’m still a Democrat and I’m not-for-profit, and that’s why our healthcare system is the way it is—it’s all for profit.”

Others in the room said also said they support changes in the country’s healthcare system but were skeptical on the candidate’s claims he’d make healthcare affordable for everyone.

“I really don’t see how he’s going to be able to make healthcare for all affordable,” said Robert Hedges. “There’s a large portion of Americans who don’t work and won’t be able to pay for it.”

Hedges, 70, of Ames, retired from his career as a family physician and is currently enrolled in Medicaid A, B and D for his drugs.

Sanders’ Medicare for all Act was proposed in 2019 and would offer health care to all Americans without deductibles, random bills and co-pays.

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Americans spend more than $10,000 per capita on health care, while countries that have universal healthcare, like Canada, France and Germany, pay less than $5,000.

Sanders will be back in Iowa on Jan. 14 for the Democratic debate at Drake University Campus in Des Moines, just three weeks before Iowa’s Feb. 3 caucuses.

----30---

#FIGHTFOR15

Will A Minimum Wage Hike Boost Mexico’s Struggling Economy?

A BMW's employee is pictured working on a BMW car assembly process in a

Will A Minimum Wage Hike Boost Mexico’s Struggling Economy?

A BMW's employee is pictured working on a BMW car assembly process in a

guided visit during the ... [+]AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

So far Mexico’s popular but polarizing president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has failed to kick-start broad-based economic growth and has focused instead on delivering increases to the country’s minimum wage on two separate occasions. Lopez Obrador raised Mexico’s minimum wage by 16% in 2019 and by additional 20% at the start of 2020.

“We continue to gradually recover the value that the minimum salary has lost over time. This is an important increase,” Lopez Obrador explained.

The move is an attempt to ameliorate the deep divisions that continue to define Mexico’s economy. Mexico has transformed over the last thirty years, buoyed by success in attracting investment in the electronics, automotive and aerospace sectors. But, while the products Mexico’s fabricates and exports have become ever more complex, overall wages in Mexico remain very low in comparison to other OECD countries. In 2018 a minimum wage worker in Mexico took home just over $2,000, around a tenth of the salary earned by minimum wage workers in France, the U.K. and Canada, and less than half of the take-home pay of minimum wage workers in Brazil and Colombia.

Overall, among industrial economies Mexico has become an anomaly for tolerating minimum wages that are dismally low by global standards. Stagnant wages have helped Mexico maintain competitiveness with China in low productivity, labor-intensive work, but low wages have also stifled the growth of a domestic market for goods and services.

Mexico’s new minimum wage won’t affect most workers but will still impact a few million families. In the third quarter of 2019 Mexico recorded nearly 10 million workers earning less than the minimum wage salary.

In 2020 minimum wage workers in Mexico will now take home 123.22 pesos (around $6.50) per day. The increase is notable, but Mexico’s daily minimum wage will still be around half of the hourly minimum wage in Arizona and California.

According to official statistics the wage hike will help at least three million people. But, it’s difficult to measure the impact of the wage hike since many workers in Mexico are employed by small family-run companies and receive cash salaries under the table. Overall in Mexico over 56% of the workforce is employed in informal sector jobs. In the under-developed south the problem is even more acute. In Chiapas, the poorest state in Mexico, a major target of attention for Lopez Obrador, over 73% of workers are employed in informal jobs. Overall in Mexico 99% of employers are small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and while a few major employers may be affected by the new minimum wage laws, the salary increase isn’t likely to catalyze broad improvements for the bulk of the population. Economists are still trying to predict whether the increase in the minimum wage in Mexico could have an impact on inflation or affect hiring in formal sector jobs.

To ask about the impact of Mexico’s new minimum wage law, I reached out to David Kaplan, Senior Labor Markets Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery: When we look at Mexico's labor market in the NAFTA-era we see signs of wage stagnation. How significant is this wage hike?

David Kaplan: Overall, Mexican wages are quite low compared to the rest of Latin America, and much lower than in countries with similar levels of GDP per capita. In 2018, in terms of average hourly wages, Mexico sat in 14th place out of the 17 Latin-American countries analyzed in the IDB’s Labor Markets and Social Security Information System, despite being the fourth richest country in terms of GDP per capita. Average wages have increased a bit in recent years but are still below 2005 levels in real terms.

A 20% increase of the minimum wage from 2019 to 2020 is obviously significant when inflation is below 3%, but in 2020 Mexico will still have one of the lowest minimum wages in the region, significantly lower than in countries with similar levels of GDP per capital like Argentina or Chile. In November of 2019, 16% of formal workers were registered with a wage less than or equal to the 2020 minimum wage. The 2020 minimum wage is equal to 54% of the median formal wage in November of 2019, which does not seem alarmingly high by international standards. For these reasons my impression is that the 2020 minimum wage will likely not be high enough to reduce formal employment in a significant way.

It is worthwhile to also consider the timing of the minimum-wage increase. Real GDP growth over the first three quarters of 2019 was close to zero. From May 2017 to May 2018, employment registered with social security increased by 4.5%. From November 2018 to November 2019, employment registered with social security grew by only 1.7%. The fact that this ambitious increase of the minimum wage comes at a time of zero economic growth and extremely sluggish growth of formal employment lends more credence to concerns of a negative impact on formal employment.

Parish Flannery: Mexico's economy is characterized by having high levels of labor market informality. What impact will this wage increase have on states in Mexico's south where the majority of people work in informal jobs?

Kaplan: A minimum-wage increase is more likely to reduce formal employment in low-wage areas, which also tend to be high-informality areas. The 2020 minimum wage is more than 60% of the November 2019 median wage in 11 states and more than two thirds of the November 2019 median wage in four states. A recent report for the UK government by Arindrajit Dube suggests that one may become more concerned about the negative impacts of minimum wages when they reach these levels.

It is useful to analyze the impact of the 2019 increase of the minimum wage at the northern border where the daily minimum wage was doubled from 88.36 pesos in 2018 to 176.72 pesos in 2019. The 2019 minimum wage at the northern border was 81.3% of the November 2018 median wage. The first impact evaluation by the Minimum Wage Commission has not shown a significant impact on formal employment, although it will be important to replicate this analysis over a longer timeframe. In general, given that an even more ambitious increase of the minimum wage at the northern border in 2019 appears to have generated small effects on formal employment, my impression is that the 2020 generalized increase of the minimum wage will not cause important reductions of formal employment, even in low-wage states.

It is also worth noting that there is an economic model that would predict that an increase of the minimum wage could increase formal employment. If employers have excessive bargaining power in the labor market, which economists call monopsony power, the increase of wages of formal jobs could attract workers from informal jobs. Some support for this hypothesis can be found in a recent study from the United States by Jose Azar, Emiliano Huet-Vaughn, Ioana Marinescu, Bledi Taska, and Till von Wachter.

Parish Flannery: Overall, what impact do you expect this wage increase to have on Mexico's economy?

Kaplan: I am extremely confident that the increase of the minimum wage will not have an important effect on inflation. The minimum wage at the northern border increased by 94.2% in real terms from November 2018 to November 2019. The average real wage for jobs registered with social security increased by only 10%. Given that the generalized minimum-wage increase in 2020 will be about 17%, it seems unlikely to me that the average real wage will increase by more than 4%. We saw average wages grow by 3.5% in 2019 overall, including the border region. So, any inflationary pressure should be manageable for the Central Bank, particularly since the annual inflation rate is currently below 3% and the annual core inflation rate has fallen from 3.85% in June to 3.65% in November. Of course, one would expect that an increase of the minimum wage would have a larger percentage effect on the wages of low-wage workers.

I am fairly confident that the increase of the minimum wage will not have an important impact on aggregate formal employment for the reasons I mentioned in my answers to the previous two questions, although the fact that the increase comes at a time when the labor market is showing clear signs of weakness is a reason for some concern. There is an economic argument developed by Daron Acemoglu that a minimum wage set to a meaningful but moderate level can cause firms to invest more in worker training and in new technologies, but I would not be confident making such a prediction.

Follow me on Twitter. Check out some of my other work here.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery

I am a Latin America focused political analyst and writer. I split my time between New York City and Mexico City. My book, Searching For Modern Mexico, was published in 2019. I have written feature articles and op-eds on business, organized crime, and politics for The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, Americas Quarterly, Fortune and a number of other publications. I have a Master's degree in International Affairs from Columbia University (SIPA). In the last few years I've had the chance to work on projects in Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, India and China.

So far Mexico’s popular but polarizing president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has failed to kick-start broad-based economic growth and has focused instead on delivering increases to the country’s minimum wage on two separate occasions. Lopez Obrador raised Mexico’s minimum wage by 16% in 2019 and by additional 20% at the start of 2020.

“We continue to gradually recover the value that the minimum salary has lost over time. This is an important increase,” Lopez Obrador explained.

The move is an attempt to ameliorate the deep divisions that continue to define Mexico’s economy. Mexico has transformed over the last thirty years, buoyed by success in attracting investment in the electronics, automotive and aerospace sectors. But, while the products Mexico’s fabricates and exports have become ever more complex, overall wages in Mexico remain very low in comparison to other OECD countries. In 2018 a minimum wage worker in Mexico took home just over $2,000, around a tenth of the salary earned by minimum wage workers in France, the U.K. and Canada, and less than half of the take-home pay of minimum wage workers in Brazil and Colombia.

Overall, among industrial economies Mexico has become an anomaly for tolerating minimum wages that are dismally low by global standards. Stagnant wages have helped Mexico maintain competitiveness with China in low productivity, labor-intensive work, but low wages have also stifled the growth of a domestic market for goods and services.

Mexico’s new minimum wage won’t affect most workers but will still impact a few million families. In the third quarter of 2019 Mexico recorded nearly 10 million workers earning less than the minimum wage salary.

In 2020 minimum wage workers in Mexico will now take home 123.22 pesos (around $6.50) per day. The increase is notable, but Mexico’s daily minimum wage will still be around half of the hourly minimum wage in Arizona and California.

According to official statistics the wage hike will help at least three million people. But, it’s difficult to measure the impact of the wage hike since many workers in Mexico are employed by small family-run companies and receive cash salaries under the table. Overall in Mexico over 56% of the workforce is employed in informal sector jobs. In the under-developed south the problem is even more acute. In Chiapas, the poorest state in Mexico, a major target of attention for Lopez Obrador, over 73% of workers are employed in informal jobs. Overall in Mexico 99% of employers are small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and while a few major employers may be affected by the new minimum wage laws, the salary increase isn’t likely to catalyze broad improvements for the bulk of the population. Economists are still trying to predict whether the increase in the minimum wage in Mexico could have an impact on inflation or affect hiring in formal sector jobs.

To ask about the impact of Mexico’s new minimum wage law, I reached out to David Kaplan, Senior Labor Markets Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery: When we look at Mexico's labor market in the NAFTA-era we see signs of wage stagnation. How significant is this wage hike?

David Kaplan: Overall, Mexican wages are quite low compared to the rest of Latin America, and much lower than in countries with similar levels of GDP per capita. In 2018, in terms of average hourly wages, Mexico sat in 14th place out of the 17 Latin-American countries analyzed in the IDB’s Labor Markets and Social Security Information System, despite being the fourth richest country in terms of GDP per capita. Average wages have increased a bit in recent years but are still below 2005 levels in real terms.

A 20% increase of the minimum wage from 2019 to 2020 is obviously significant when inflation is below 3%, but in 2020 Mexico will still have one of the lowest minimum wages in the region, significantly lower than in countries with similar levels of GDP per capital like Argentina or Chile. In November of 2019, 16% of formal workers were registered with a wage less than or equal to the 2020 minimum wage. The 2020 minimum wage is equal to 54% of the median formal wage in November of 2019, which does not seem alarmingly high by international standards. For these reasons my impression is that the 2020 minimum wage will likely not be high enough to reduce formal employment in a significant way.

It is worthwhile to also consider the timing of the minimum-wage increase. Real GDP growth over the first three quarters of 2019 was close to zero. From May 2017 to May 2018, employment registered with social security increased by 4.5%. From November 2018 to November 2019, employment registered with social security grew by only 1.7%. The fact that this ambitious increase of the minimum wage comes at a time of zero economic growth and extremely sluggish growth of formal employment lends more credence to concerns of a negative impact on formal employment.

Parish Flannery: Mexico's economy is characterized by having high levels of labor market informality. What impact will this wage increase have on states in Mexico's south where the majority of people work in informal jobs?

Kaplan: A minimum-wage increase is more likely to reduce formal employment in low-wage areas, which also tend to be high-informality areas. The 2020 minimum wage is more than 60% of the November 2019 median wage in 11 states and more than two thirds of the November 2019 median wage in four states. A recent report for the UK government by Arindrajit Dube suggests that one may become more concerned about the negative impacts of minimum wages when they reach these levels.

It is useful to analyze the impact of the 2019 increase of the minimum wage at the northern border where the daily minimum wage was doubled from 88.36 pesos in 2018 to 176.72 pesos in 2019. The 2019 minimum wage at the northern border was 81.3% of the November 2018 median wage. The first impact evaluation by the Minimum Wage Commission has not shown a significant impact on formal employment, although it will be important to replicate this analysis over a longer timeframe. In general, given that an even more ambitious increase of the minimum wage at the northern border in 2019 appears to have generated small effects on formal employment, my impression is that the 2020 generalized increase of the minimum wage will not cause important reductions of formal employment, even in low-wage states.

It is also worth noting that there is an economic model that would predict that an increase of the minimum wage could increase formal employment. If employers have excessive bargaining power in the labor market, which economists call monopsony power, the increase of wages of formal jobs could attract workers from informal jobs. Some support for this hypothesis can be found in a recent study from the United States by Jose Azar, Emiliano Huet-Vaughn, Ioana Marinescu, Bledi Taska, and Till von Wachter.

Parish Flannery: Overall, what impact do you expect this wage increase to have on Mexico's economy?

Kaplan: I am extremely confident that the increase of the minimum wage will not have an important effect on inflation. The minimum wage at the northern border increased by 94.2% in real terms from November 2018 to November 2019. The average real wage for jobs registered with social security increased by only 10%. Given that the generalized minimum-wage increase in 2020 will be about 17%, it seems unlikely to me that the average real wage will increase by more than 4%. We saw average wages grow by 3.5% in 2019 overall, including the border region. So, any inflationary pressure should be manageable for the Central Bank, particularly since the annual inflation rate is currently below 3% and the annual core inflation rate has fallen from 3.85% in June to 3.65% in November. Of course, one would expect that an increase of the minimum wage would have a larger percentage effect on the wages of low-wage workers.

I am fairly confident that the increase of the minimum wage will not have an important impact on aggregate formal employment for the reasons I mentioned in my answers to the previous two questions, although the fact that the increase comes at a time when the labor market is showing clear signs of weakness is a reason for some concern. There is an economic argument developed by Daron Acemoglu that a minimum wage set to a meaningful but moderate level can cause firms to invest more in worker training and in new technologies, but I would not be confident making such a prediction.

---30---

Follow me on Twitter. Check out some of my other work here.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery

I am a Latin America focused political analyst and writer. I split my time between New York City and Mexico City. My book, Searching For Modern Mexico, was published in 2019. I have written feature articles and op-eds on business, organized crime, and politics for The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, Americas Quarterly, Fortune and a number of other publications. I have a Master's degree in International Affairs from Columbia University (SIPA). In the last few years I've had the chance to work on projects in Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, India and China.

#FIGHTFOR15

USA

When Prices Increase, But The Minimum Wage Has Not

By EDITOR •

The federal minimum wage hasn't gone up since 2009. But the price of almost everything else has.

TYRONE TURNER/WAMU

The federal minimum wage is $7.25. And that rate hasn’t changed in 10 years, even though the price of everything from housing to transportation has increased.

But new reporting shows that wages around the country have grown, in part due to state and local measures which increase the minimum wage.

In Washington D.C., paying a living wage means a rate of $14.50 an hour. But even then, some workers say it’s not enough to make ends meet.

WAMU’s Sasha-Ann Simons spoke to Ed Lazere, the executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. He told her that in D.C., “the minimum wage is a floor, and the living wage should be something that is much closer to what it really takes to live on,” and added, “we’re going to be at the weird point in a year where the living wage is actually the minimum wage, and that’s clearly a bad place to be.”

Is it enough? Are businesses or the government responsible for ensuring everyone makes a salary on which they can live?

In partnership with our home station’s Affordability Desk, this is the beginning of our series on the cost of living around the country.

We’re calling the series “Priced Out,” and throughout, we want to hear from you. What do you need to make every month to live in the U.S. and have your basic needs met? And who do you think is responsible for providing a living wage?

Produced by Morgan Givens.

GUESTS

Adriana Kugler, Professor of economics and foreign policy, Georgetown University; former Chief Economist, United States Department of Labor (Obama Administration 2011 – 2013)

David Cooper, Senior economic analyst, Economic Policy Institute; deputy director, Economic Analysis and Research Network; @metaCoop

Sasha-Ann Simons, Race & Identity Reporter, WAMU 88.5; @SashaAnnSimons

For more, visit https://the1a.org.

© 2020 WAMU 88.5 – American University Radio.

USA

When Prices Increase, But The Minimum Wage Has Not

By EDITOR •

The federal minimum wage hasn't gone up since 2009. But the price of almost everything else has.

TYRONE TURNER/WAMU

The federal minimum wage is $7.25. And that rate hasn’t changed in 10 years, even though the price of everything from housing to transportation has increased.

But new reporting shows that wages around the country have grown, in part due to state and local measures which increase the minimum wage.

In Washington D.C., paying a living wage means a rate of $14.50 an hour. But even then, some workers say it’s not enough to make ends meet.

WAMU’s Sasha-Ann Simons spoke to Ed Lazere, the executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. He told her that in D.C., “the minimum wage is a floor, and the living wage should be something that is much closer to what it really takes to live on,” and added, “we’re going to be at the weird point in a year where the living wage is actually the minimum wage, and that’s clearly a bad place to be.”

Is it enough? Are businesses or the government responsible for ensuring everyone makes a salary on which they can live?

In partnership with our home station’s Affordability Desk, this is the beginning of our series on the cost of living around the country.

We’re calling the series “Priced Out,” and throughout, we want to hear from you. What do you need to make every month to live in the U.S. and have your basic needs met? And who do you think is responsible for providing a living wage?

Produced by Morgan Givens.

GUESTS

Adriana Kugler, Professor of economics and foreign policy, Georgetown University; former Chief Economist, United States Department of Labor (Obama Administration 2011 – 2013)

David Cooper, Senior economic analyst, Economic Policy Institute; deputy director, Economic Analysis and Research Network; @metaCoop

Sasha-Ann Simons, Race & Identity Reporter, WAMU 88.5; @SashaAnnSimons

For more, visit https://the1a.org.

© 2020 WAMU 88.5 – American University Radio.

#FIGHTFOR15

USA

Case for $15 minimum federal wage convincing

The New York Times Editorial

This editorial first appeared in The New York Times.

USA

Case for $15 minimum federal wage convincing

The New York Times Editorial

This editorial first appeared in The New York Times.

Guest editorials don’t necessarily reflect the Denton Record-Chronicle’s opinions.

Opponents of minimum-wage laws have long argued that companies have only so much money and, if required to pay higher wages, they will employ fewer workers.

Opponents of minimum-wage laws have long argued that companies have only so much money and, if required to pay higher wages, they will employ fewer workers.

Now there is evidence that such concerns, never entirely sincere, are greatly overstated.

Over the past five years, a wave of increases in state and local minimum-wage standards has pushed the average effective minimum wage in the United States to the highest level on record. The average worker must be paid at least $11.80 an hour — more after inflation than the last peak, in the 1960s, according to an analysis by the economist Ernie Tedeschi.

And even as wages have marched upward, job growth remains strong. The unemployment rate at the end of 2019 will be lower than the previous year for the 10th straight year.

The interventions by some state and local governments, however, do not obviate the need for federal action. To the contrary. Millions of workers are being left behind because 21 states still use the federal standard, $7.25 an hour, which has not risen since 2009 — the longest period without an increase since the introduction of a federal standard in the 1930s.

Across much of America, the minimum wage is set to rise again in the next few days. In Maine and Colorado it will reach $12; in Washington, $13.50; in New York City, $15. Workers in the rest of the country also deserve a raise. The time has come to increase the federal minimum.

House Democrats passed legislation in July that would gradually increase the federal standard to $15 an hour in 2025 — likely raising the real value above the peak value in the late 1960s — and most of the Democrats running for president have endorsed the legislation. Last year, only about 430,000 people — or 0.5% of hourly workers — were paid the federal minimum. The share has fallen in recent years as state and local governments, and some employers, have stepped in. But a much larger group of workers stand to benefit, because they now earn less than the proposed minimum. The Congressional Budget Office estimated a $15 minimum hourly wage would raise the pay of at least 17 million workers.

Among the beneficiaries: people who work for tips. Federal law lets businesses pay $2.13 an hour to waiters, bartenders and others who get tips, so long as the total of tips and wages meets the federal minimum. The legislation would end that rule; the same minimum would apply to all hourly employees. Opponents of the change argue customers will curtail tipping and workers will end up with less money. But eight states, including Minnesota, Montana and Oregon, already have a universal minimum, including for tipped workers, and restaurant workers in those states make more money.

Crucially, the legislation also would require automatic adjustments in the minimum wage to keep pace with wage growth in the broader economy. The current minimum rises only when Congress is in the mood. As a result, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has eroded by nearly 40% over the past half-century. A full-time worker making the minimum wage cannot afford a one-bedroom apartment in almost any American city.

The simplistic view that minimum-wage laws cause unemployment commanded such a broad consensus in the 1980s that this editorial board came out against the federal minimum in 1987, calling it “an idea whose time has passed,” and citing as evidence “a virtual consensus among economists.” The old critique is still put forward regularly by the restaurant industry and other major employers of low-wage workers.

But evidence that any such effects are relatively small has been piling up for several decades. A groundbreaking study published in 1993 by the economists David Card and Alan Krueger examined a minimum-wage rise in New Jersey by comparing fast-food restaurants there and in an adjacent part of Pennsylvania. It found no impact on employment.

This prompted other economists to test the standard theory. This year, the British government asked the economist Arindrajit Dube to review the results accumulated over the last quarter-century. Mr. Dube reported the sum total of the research showed minimum-wage increases raised compensation while producing a “very muted effect” on employment.

The patchwork nature of recent minimum-wage increases — the rate rising in some jurisdictions while staying the same in adjacent areas — is offering new opportunities for research.

For most companies, the bill is relatively small, and it can be defrayed by giving less money to shareholders, or by raising prices. Opponents often argue minimum-wage increases will encourage automation, but the point is easily overstated. Companies constantly invest in technology: McDonald’s is installing self-order kiosks across the United States, not just at places with higher minimum wages. And instead of replacing workers with robots, companies may choose to invest in technology that enhances the productivity of their workforce.

More than doubling the current federal standard would be a significant change, and it is not without risk. It is possible that a national $15 standard would produce the kinds of damage critics have long predicted; the Congressional Budget Office puts the potential increase in unemployment somewhere between zero and 3.7 million people, essentially acknowledging the effects are unpredictable.

One simple corrective, proposed by Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, would be to include exemptions from the $15 standard for low-wage metropolitan areas and rural areas.

But the successful increases in minimum-wage standards across a diverse range of states and cities suggest the broader risk is worth taking. The American economy is generating plenty of jobs; the problem is in the paychecks. The solution is a $15 federal minimum wage.

Over the past five years, a wave of increases in state and local minimum-wage standards has pushed the average effective minimum wage in the United States to the highest level on record. The average worker must be paid at least $11.80 an hour — more after inflation than the last peak, in the 1960s, according to an analysis by the economist Ernie Tedeschi.

And even as wages have marched upward, job growth remains strong. The unemployment rate at the end of 2019 will be lower than the previous year for the 10th straight year.

The interventions by some state and local governments, however, do not obviate the need for federal action. To the contrary. Millions of workers are being left behind because 21 states still use the federal standard, $7.25 an hour, which has not risen since 2009 — the longest period without an increase since the introduction of a federal standard in the 1930s.

Across much of America, the minimum wage is set to rise again in the next few days. In Maine and Colorado it will reach $12; in Washington, $13.50; in New York City, $15. Workers in the rest of the country also deserve a raise. The time has come to increase the federal minimum.

House Democrats passed legislation in July that would gradually increase the federal standard to $15 an hour in 2025 — likely raising the real value above the peak value in the late 1960s — and most of the Democrats running for president have endorsed the legislation. Last year, only about 430,000 people — or 0.5% of hourly workers — were paid the federal minimum. The share has fallen in recent years as state and local governments, and some employers, have stepped in. But a much larger group of workers stand to benefit, because they now earn less than the proposed minimum. The Congressional Budget Office estimated a $15 minimum hourly wage would raise the pay of at least 17 million workers.

Among the beneficiaries: people who work for tips. Federal law lets businesses pay $2.13 an hour to waiters, bartenders and others who get tips, so long as the total of tips and wages meets the federal minimum. The legislation would end that rule; the same minimum would apply to all hourly employees. Opponents of the change argue customers will curtail tipping and workers will end up with less money. But eight states, including Minnesota, Montana and Oregon, already have a universal minimum, including for tipped workers, and restaurant workers in those states make more money.

Crucially, the legislation also would require automatic adjustments in the minimum wage to keep pace with wage growth in the broader economy. The current minimum rises only when Congress is in the mood. As a result, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has eroded by nearly 40% over the past half-century. A full-time worker making the minimum wage cannot afford a one-bedroom apartment in almost any American city.

The simplistic view that minimum-wage laws cause unemployment commanded such a broad consensus in the 1980s that this editorial board came out against the federal minimum in 1987, calling it “an idea whose time has passed,” and citing as evidence “a virtual consensus among economists.” The old critique is still put forward regularly by the restaurant industry and other major employers of low-wage workers.

But evidence that any such effects are relatively small has been piling up for several decades. A groundbreaking study published in 1993 by the economists David Card and Alan Krueger examined a minimum-wage rise in New Jersey by comparing fast-food restaurants there and in an adjacent part of Pennsylvania. It found no impact on employment.

This prompted other economists to test the standard theory. This year, the British government asked the economist Arindrajit Dube to review the results accumulated over the last quarter-century. Mr. Dube reported the sum total of the research showed minimum-wage increases raised compensation while producing a “very muted effect” on employment.

The patchwork nature of recent minimum-wage increases — the rate rising in some jurisdictions while staying the same in adjacent areas — is offering new opportunities for research.

For most companies, the bill is relatively small, and it can be defrayed by giving less money to shareholders, or by raising prices. Opponents often argue minimum-wage increases will encourage automation, but the point is easily overstated. Companies constantly invest in technology: McDonald’s is installing self-order kiosks across the United States, not just at places with higher minimum wages. And instead of replacing workers with robots, companies may choose to invest in technology that enhances the productivity of their workforce.

More than doubling the current federal standard would be a significant change, and it is not without risk. It is possible that a national $15 standard would produce the kinds of damage critics have long predicted; the Congressional Budget Office puts the potential increase in unemployment somewhere between zero and 3.7 million people, essentially acknowledging the effects are unpredictable.

One simple corrective, proposed by Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, would be to include exemptions from the $15 standard for low-wage metropolitan areas and rural areas.

But the successful increases in minimum-wage standards across a diverse range of states and cities suggest the broader risk is worth taking. The American economy is generating plenty of jobs; the problem is in the paychecks. The solution is a $15 federal minimum wage.

---30---

#FIGHTFOR15

USA

Pay Is Rising Fastest for Low Earners. One Reason? Minimum Wages.

Increases in minimum wages across the country may make the labor market look a bit rosier than it really is.

By Ernie Tedeschi

Jan. 3, 2020 NYT

These days, wages in the United States are doing something extraordinary: They’re growing faster at the bottom than at the top. In fact, recent growth for workers with low wages has outpaced that for high-wage workers by the widest margin in at least 20 years.

The main story here is the long economic recovery, now entering its 11th year. For much of the early phase of this recovery, wage growth for the bottom group was weaker than for others, but it began gradually accelerating in 2014 as unemployment continued to fall. This was around the same time the labor market started tapping into people some economists had all but given up on as work force participants, such as those who had been citing health reasons or disability for not having a job.

But there has been another factor at play: the rise in state and local minimum wages.

For the last decade, the federal minimum wage has been unchanged at $7.25 an hour. But over that period, dozens of states and localities have enacted their own minimum wages or raised existing ones. As a result, the effective U.S. minimum wage is closer to $12 an hour, most likely the highest in U.S. history even after adjusting for inflation.

And with two dozen states and four dozen localities set to raise their minimums further in 2020, the effective minimum wage will keep rising this year.

These state and local actions are affecting wage data, especially for workers at the bottom. To get a sense of this impact, I have used data in the Current Population Survey to look at minimum wage workers as a group and calculate the pressure their wage gains have put on aggregate wage growth over time, controlling for compositional changes in the share of minimum wage work.

Americans Are Seeing Highest Minimum Wage in History (Without Federal Help)April 24, 2019

Note that this approach doesn’t settle whether minimum-wage increases are a net benefit to Americans, since among other things wage data will by definition capture only those who stayed employed after an increase. If people were laid off because of a minimum-wage increase, their loss of wages wouldn’t factor into the average.

This analysis shows that growth in average wages has been running about 3.9 percent per year in the Current Population Survey over the past two years, a bit firmer than the pace right before the Great Recession but below the near 5 percent reached in 2000.

But increases to minimum wages at the state and local level have put 0.4 percentage points of upward pressure on this recent growth. Absent that pressure, wage growth in the Current Population Survey over the last two years would have been 3.5 percent. That’s still a fine result, but it’s a bit cooler than the unadjusted data suggest.

Wage pressure from minimum wage workers is magnified when you look at only the lowest wages. That’s because while minimum wage work makes up about 6 percent of all usual hours worked, it’s around 13 percent of hours worked by Americans in the bottom third of wages.

As the analysis has shown us, wage growth at the bottom is doing well. It has been around 4.1 percent over the last two years — above the 3.6 percent at the top end, and above the overall average of 3.9 percent.

But absent the pressure from minimum wage workers, growth at the bottom would have been closer to 3.3 percent.

It’s important to keep the effect of these minimum wage increases in perspective. The increases aren’t responsible for most of the wage growth, or for most of the acceleration in wage growth, during this recovery. Even among the bottom third, minimum wage workers have contributed around a fifth to a quarter of wage growth over the last two years.

As notable as the recent rise in state and local minimum wages has been to this effect, it has probably not been as important as the tightening labor market. In a tight labor market, firms have to compete more to hire and retain the workers they need, which among other things gives those workers more bargaining power to bid up their wages.

The Federal Reserve chair, Jerome Powell, has argued that reaching workers traditionally “left behind” is one of the most compelling reasons to sustain the expansion for as long as possible.

Still, this analysis suggests these minimum-wage increases are having a meaningful impact on wages, at least for the employed workers who benefit from them. For the bottom third, state and local minimum wage increases have probably been the difference between the wage growth just before the economic crisis and the wage growth that is now above that pace.

But that benefit also brings with it a cautionary note for policymakers.

Economists look to wages as one thermometer of how hot the economy is getting: Accelerating wages may eventually spill over into higher prices and signal an economy at capacity, though this hasn’t happened yet in this recovery.

But these continuing increases to state and local minimum wages — and any possible future action at the federal level — could skew wage data, making the American labor market look tighter than it actually is.

The recent rise in minimum wages, although not producing a giant effect, still might suggest overall wage growth is progressing about a year further along than the reality. For low-wage workers, whom policymakers are citing more often, the minimum wage effect can be worth closer to two years’ worth of wage acceleration.

The risk of misdiagnosing an overheating economy is one reason it’s important to be clear and precise about what role minimum wage increases have played in recent wage growth: They have been important, but they’re most likely not the biggest factor.

Methodology: This analysis defines “minimum wage pressure” as the growth in the effective minimum wage — the average binding federal, state or local minimum wage received per hour of minimum wage work — over 12 months, weighted by the share of minimum wage work at the beginning of the 12-month period. In a shift-share framework, this is the equivalent of the compositionally adjusted contribution to aggregate wage growth from minimum wage workers.

The analysis uses average hourly wages for private nonfarm wage and salary workers calculated from the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group. It takes hourly wages as given when available for hourly workers; for others, it divides usual weekly earnings by usual weekly hours. The analysis imputes usual hours when unavailable or varying, and adjusts weekly earnings for top-coding using a log-linear distributional assumption. It also trims outlier hourly wages. Despite these adjustments, wages in the C.P.S. invariably differ from average hourly earnings reported in the Current Employment Statistics, another Bureau of Labor Statistics data source for wages, because of differences in scope, design and concept.

The analysis uses the same methodology for calculating state and local minimum wages, and for identifying minimum wage workers, as in a previous analysis from April 2019.

Ernie Tedeschi is an economist and head of fiscal analysis at Evercore ISI. He worked previously at the U.S. Treasury Department. The analysis here is solely his own. You can follow him on Twitter at @ernietedeschi.

A version of this article appears in print on Jan. 6, 2020, Section B, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Wages Rise At Low End, Gilding Data.

THE ABOVE ARTICLE INCLUDES CHARTS NOT AVAILABLE HERE

Americans Are Seeing Highest Minimum Wage in History (Without Federal Help)

Because of moves by states and cities in recent years, the effective average is almost at $12 an hour.

By Ernie Tedeschi

April 24, 2019

ImageProtestors called for higher wages near a Las Vegas McDonald’s in 2016. Nevada’s minimum wage is currently $7.25 per hour for employees with health benefits and $8.25 for those without.Credit...John Locher/Associated Press

The federal minimum wage rose to $7.25 an hour 10 years ago. It hasn’t budged since.

For Americans living in the 21 states where the federal minimum wage is binding, inflation means that the minimum wage has lost 16 percent of its purchasing power.

But elsewhere, many workers and employers are experiencing a minimum wage well above 2009 levels. That’s because state capitols and, to an unprecedented degree, city halls have become far more active in setting their own minimum wages.

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have state-level minimum hourly wages higher than the federal one. In Washington State and Massachusetts, for example, it’s $12.

But the true sea change is in the surge of city and county governments setting minimums. New York City has a $15 minimum wage, while in SeaTac, Wash., it’s $16.09.

Averaging across all of these federal, state and local minimum wage laws, the effective minimum wage in the United States — the average minimum wage binding each hour of minimum wage work — will be $11.80 an hour in 2019. Adjusted for inflation, this is probably the highest minimum wage in American history.

Growth in the Effective Minimum Has Taken Off in Recent Years

The effective minimum wage has not only outpaced inflation in recent years, but it has also grown faster than typical wages. We can see this from the Kaitz index, which compares the minimum wage with median overall wages.

To put the growth in perspective: It took the 19 years ending in 2013 for the Kaitz index to rise four percentage points. In the six years since 2013, it has risen 13 percentage points.

The Federal Minimum Affects Only a Small Share of Minimum Wage Workers

Minimum wage laws above the federal level used to be the exception. In 1998, there were about a million minimum-wage workers in states with a minimum higher than the federal level, and virtually none in localities with separate minimums. Two-thirds of minimum wage workers lived in areas where the federal minimum applied.

But today 89 percent of the nation’s 6.8 million minimum-wage employees face a minimum that is higher than $7.25 an hour. Even five years ago, relatively few such workers lived in areas with separate local minimum wages.

One consequence is increasing regional variation. American minimum wages now range from New York State’s effective $13.73, which is 62 percent of the state’s median overall wage, down to New Hampshire’s $7.25 federal peg, which is just 30 percent of the state median.

Higher Minimum Wages Have Boosted Wage Growth at the Bottom …

The most important question, though, is how the extraordinary rise in the effective minimum wage has affected American workers.

First, the good news: The average wage in the bottom third of the wage distribution — minimum-wage workers and others — has risen an average of 2.3 percent annually over the last three years after adjusting for inflation. The growth pressure from the wages of workers at or just around the minimum wage can account for between a quarter to a third of this growth.

Clearly state and local minimum-wage increases make a difference for workers who live and can find jobs in the places affected by them, even if this is not a complete explanation for the recent wage growth at the bottom nationally.

… But Like All Public Policies, Minimum Wage Increases Have Trade-Offs

Traditional textbook economics tells us that employers will cut jobs or hours for low-wage work if they’re required to set the price of labor above the level consistent with market supply and demand. Therein lies one of the most contentious debates in economics right now.

In the real world, it’s difficult to test this because of so many confounding factors.

For example, teenage employment rose about as much between 2013 and 2018 in states whose effective minimum wage didn’t change as it did in states where it rose an average of 4 percent or greater each year.

The places that chose to raise their minimum wages may be different in important respects, both socioeconomic and demographic, from those that did not, like education; industry and occupation; and labor market health.

A sizable body of empirical research that adjusts for these issues concludes that while some workers are winners from minimum wage increases, many others lose out, particularly vulnerable workers like the young and those with less education. This calls into question whether raising the minimum wage is really the best way to help workers.

But beginning with David Card and Alan Krueger’s landmark 1994 study of New Jersey’s minimum wage increase, a growing economics literature is reaching a different conclusion: that the jobs effects found in these other studies is overstated, and that the rising minimum wages in the United States have had more of a net benefit.

For example, a huge study released this month analyzed 138 different state-level minimum wage increases since 1979. The authors found largely no net negative employment effects, though they did find some in sectors exposed to international trade. And University of Washington economists revised an initial study of Seattle’s recent minimum wage increase that had showed significant negative effects on earnings for some workers. The new study found that the downsides were more muted.

Economists have several ideas for why negative jobs effects might be lower than expected. Employers may be less sensitive to minimum-wage increases because of long-term declines in national business competition and labor bargaining power, and the rise in profit rates and monopsony (in which a single buyer dominates a market).

The tightness of today’s labor market may also help explain why it’s hard to see much effect from recent increases. Perhaps minimum wages really “bite” only when they exceed a certain level. Or maybe employers have been reacting to them in ways not easily captured by wage data, such as by cutting benefits.

The push for higher state and local minimum wages shows no sign of abating, so no doubt we’ll learn even more in coming years about their trade-offs, or lack thereof.

Methodology: The effective minimum wage is the binding federal, state or local minimum wage weighted by the usual labor hours of minimum wage workers at nonfarm wage and salary jobs paid hourly. It includes all federal and state laws as well as 32 localities with separate ordinances whose geography we can identify in the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group. We exclude tipped occupations from this calculation using the definitions used by the Economic Policy Institute. We calculate median overall wages and average hourly earnings in the C.P.S. to be conceptually similar to average hourly earnings in the Current Employment Statistics survey. Inflation-adjusted series use the chained C.P.I.-U deflator, which is extended before 2000 using the deflator for personal consumption expenditures. This analysis uses data on local minimum wage ordinances from the U.C. Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education as well as from Kavya Vaghul and Ben Zipperer.

Ernie Tedeschi is an economist and head of fiscal analysis at Evercore ISI. He worked previously at the U.S. Treasury Department. The analysis here is solely his own. You can follow him on Twitter at @ernietedeschi.

A version of this article appears in print on April 29, 2019, Section A, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: Minimum Wage at Record High (Without Federal Help). Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

USA

Pay Is Rising Fastest for Low Earners. One Reason? Minimum Wages.

Increases in minimum wages across the country may make the labor market look a bit rosier than it really is.

By Ernie Tedeschi

Jan. 3, 2020 NYT

These days, wages in the United States are doing something extraordinary: They’re growing faster at the bottom than at the top. In fact, recent growth for workers with low wages has outpaced that for high-wage workers by the widest margin in at least 20 years.

The main story here is the long economic recovery, now entering its 11th year. For much of the early phase of this recovery, wage growth for the bottom group was weaker than for others, but it began gradually accelerating in 2014 as unemployment continued to fall. This was around the same time the labor market started tapping into people some economists had all but given up on as work force participants, such as those who had been citing health reasons or disability for not having a job.

But there has been another factor at play: the rise in state and local minimum wages.

For the last decade, the federal minimum wage has been unchanged at $7.25 an hour. But over that period, dozens of states and localities have enacted their own minimum wages or raised existing ones. As a result, the effective U.S. minimum wage is closer to $12 an hour, most likely the highest in U.S. history even after adjusting for inflation.

And with two dozen states and four dozen localities set to raise their minimums further in 2020, the effective minimum wage will keep rising this year.

These state and local actions are affecting wage data, especially for workers at the bottom. To get a sense of this impact, I have used data in the Current Population Survey to look at minimum wage workers as a group and calculate the pressure their wage gains have put on aggregate wage growth over time, controlling for compositional changes in the share of minimum wage work.

Americans Are Seeing Highest Minimum Wage in History (Without Federal Help)April 24, 2019

Note that this approach doesn’t settle whether minimum-wage increases are a net benefit to Americans, since among other things wage data will by definition capture only those who stayed employed after an increase. If people were laid off because of a minimum-wage increase, their loss of wages wouldn’t factor into the average.

This analysis shows that growth in average wages has been running about 3.9 percent per year in the Current Population Survey over the past two years, a bit firmer than the pace right before the Great Recession but below the near 5 percent reached in 2000.

But increases to minimum wages at the state and local level have put 0.4 percentage points of upward pressure on this recent growth. Absent that pressure, wage growth in the Current Population Survey over the last two years would have been 3.5 percent. That’s still a fine result, but it’s a bit cooler than the unadjusted data suggest.

Wage pressure from minimum wage workers is magnified when you look at only the lowest wages. That’s because while minimum wage work makes up about 6 percent of all usual hours worked, it’s around 13 percent of hours worked by Americans in the bottom third of wages.

As the analysis has shown us, wage growth at the bottom is doing well. It has been around 4.1 percent over the last two years — above the 3.6 percent at the top end, and above the overall average of 3.9 percent.

But absent the pressure from minimum wage workers, growth at the bottom would have been closer to 3.3 percent.

It’s important to keep the effect of these minimum wage increases in perspective. The increases aren’t responsible for most of the wage growth, or for most of the acceleration in wage growth, during this recovery. Even among the bottom third, minimum wage workers have contributed around a fifth to a quarter of wage growth over the last two years.

As notable as the recent rise in state and local minimum wages has been to this effect, it has probably not been as important as the tightening labor market. In a tight labor market, firms have to compete more to hire and retain the workers they need, which among other things gives those workers more bargaining power to bid up their wages.

The Federal Reserve chair, Jerome Powell, has argued that reaching workers traditionally “left behind” is one of the most compelling reasons to sustain the expansion for as long as possible.

Still, this analysis suggests these minimum-wage increases are having a meaningful impact on wages, at least for the employed workers who benefit from them. For the bottom third, state and local minimum wage increases have probably been the difference between the wage growth just before the economic crisis and the wage growth that is now above that pace.

But that benefit also brings with it a cautionary note for policymakers.

Economists look to wages as one thermometer of how hot the economy is getting: Accelerating wages may eventually spill over into higher prices and signal an economy at capacity, though this hasn’t happened yet in this recovery.

But these continuing increases to state and local minimum wages — and any possible future action at the federal level — could skew wage data, making the American labor market look tighter than it actually is.

The recent rise in minimum wages, although not producing a giant effect, still might suggest overall wage growth is progressing about a year further along than the reality. For low-wage workers, whom policymakers are citing more often, the minimum wage effect can be worth closer to two years’ worth of wage acceleration.

The risk of misdiagnosing an overheating economy is one reason it’s important to be clear and precise about what role minimum wage increases have played in recent wage growth: They have been important, but they’re most likely not the biggest factor.

Methodology: This analysis defines “minimum wage pressure” as the growth in the effective minimum wage — the average binding federal, state or local minimum wage received per hour of minimum wage work — over 12 months, weighted by the share of minimum wage work at the beginning of the 12-month period. In a shift-share framework, this is the equivalent of the compositionally adjusted contribution to aggregate wage growth from minimum wage workers.

The analysis uses average hourly wages for private nonfarm wage and salary workers calculated from the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group. It takes hourly wages as given when available for hourly workers; for others, it divides usual weekly earnings by usual weekly hours. The analysis imputes usual hours when unavailable or varying, and adjusts weekly earnings for top-coding using a log-linear distributional assumption. It also trims outlier hourly wages. Despite these adjustments, wages in the C.P.S. invariably differ from average hourly earnings reported in the Current Employment Statistics, another Bureau of Labor Statistics data source for wages, because of differences in scope, design and concept.

The analysis uses the same methodology for calculating state and local minimum wages, and for identifying minimum wage workers, as in a previous analysis from April 2019.

Ernie Tedeschi is an economist and head of fiscal analysis at Evercore ISI. He worked previously at the U.S. Treasury Department. The analysis here is solely his own. You can follow him on Twitter at @ernietedeschi.

A version of this article appears in print on Jan. 6, 2020, Section B, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Wages Rise At Low End, Gilding Data.

THE ABOVE ARTICLE INCLUDES CHARTS NOT AVAILABLE HERE

Americans Are Seeing Highest Minimum Wage in History (Without Federal Help)

Because of moves by states and cities in recent years, the effective average is almost at $12 an hour.

By Ernie Tedeschi

April 24, 2019

ImageProtestors called for higher wages near a Las Vegas McDonald’s in 2016. Nevada’s minimum wage is currently $7.25 per hour for employees with health benefits and $8.25 for those without.Credit...John Locher/Associated Press

The federal minimum wage rose to $7.25 an hour 10 years ago. It hasn’t budged since.

For Americans living in the 21 states where the federal minimum wage is binding, inflation means that the minimum wage has lost 16 percent of its purchasing power.

But elsewhere, many workers and employers are experiencing a minimum wage well above 2009 levels. That’s because state capitols and, to an unprecedented degree, city halls have become far more active in setting their own minimum wages.

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have state-level minimum hourly wages higher than the federal one. In Washington State and Massachusetts, for example, it’s $12.

But the true sea change is in the surge of city and county governments setting minimums. New York City has a $15 minimum wage, while in SeaTac, Wash., it’s $16.09.

Averaging across all of these federal, state and local minimum wage laws, the effective minimum wage in the United States — the average minimum wage binding each hour of minimum wage work — will be $11.80 an hour in 2019. Adjusted for inflation, this is probably the highest minimum wage in American history.

Growth in the Effective Minimum Has Taken Off in Recent Years

The effective minimum wage has not only outpaced inflation in recent years, but it has also grown faster than typical wages. We can see this from the Kaitz index, which compares the minimum wage with median overall wages.

To put the growth in perspective: It took the 19 years ending in 2013 for the Kaitz index to rise four percentage points. In the six years since 2013, it has risen 13 percentage points.

The Federal Minimum Affects Only a Small Share of Minimum Wage Workers

Minimum wage laws above the federal level used to be the exception. In 1998, there were about a million minimum-wage workers in states with a minimum higher than the federal level, and virtually none in localities with separate minimums. Two-thirds of minimum wage workers lived in areas where the federal minimum applied.

But today 89 percent of the nation’s 6.8 million minimum-wage employees face a minimum that is higher than $7.25 an hour. Even five years ago, relatively few such workers lived in areas with separate local minimum wages.

One consequence is increasing regional variation. American minimum wages now range from New York State’s effective $13.73, which is 62 percent of the state’s median overall wage, down to New Hampshire’s $7.25 federal peg, which is just 30 percent of the state median.

Higher Minimum Wages Have Boosted Wage Growth at the Bottom …

The most important question, though, is how the extraordinary rise in the effective minimum wage has affected American workers.

First, the good news: The average wage in the bottom third of the wage distribution — minimum-wage workers and others — has risen an average of 2.3 percent annually over the last three years after adjusting for inflation. The growth pressure from the wages of workers at or just around the minimum wage can account for between a quarter to a third of this growth.

Clearly state and local minimum-wage increases make a difference for workers who live and can find jobs in the places affected by them, even if this is not a complete explanation for the recent wage growth at the bottom nationally.

… But Like All Public Policies, Minimum Wage Increases Have Trade-Offs

Traditional textbook economics tells us that employers will cut jobs or hours for low-wage work if they’re required to set the price of labor above the level consistent with market supply and demand. Therein lies one of the most contentious debates in economics right now.

In the real world, it’s difficult to test this because of so many confounding factors.

For example, teenage employment rose about as much between 2013 and 2018 in states whose effective minimum wage didn’t change as it did in states where it rose an average of 4 percent or greater each year.

The places that chose to raise their minimum wages may be different in important respects, both socioeconomic and demographic, from those that did not, like education; industry and occupation; and labor market health.

A sizable body of empirical research that adjusts for these issues concludes that while some workers are winners from minimum wage increases, many others lose out, particularly vulnerable workers like the young and those with less education. This calls into question whether raising the minimum wage is really the best way to help workers.

But beginning with David Card and Alan Krueger’s landmark 1994 study of New Jersey’s minimum wage increase, a growing economics literature is reaching a different conclusion: that the jobs effects found in these other studies is overstated, and that the rising minimum wages in the United States have had more of a net benefit.

For example, a huge study released this month analyzed 138 different state-level minimum wage increases since 1979. The authors found largely no net negative employment effects, though they did find some in sectors exposed to international trade. And University of Washington economists revised an initial study of Seattle’s recent minimum wage increase that had showed significant negative effects on earnings for some workers. The new study found that the downsides were more muted.

Economists have several ideas for why negative jobs effects might be lower than expected. Employers may be less sensitive to minimum-wage increases because of long-term declines in national business competition and labor bargaining power, and the rise in profit rates and monopsony (in which a single buyer dominates a market).

The tightness of today’s labor market may also help explain why it’s hard to see much effect from recent increases. Perhaps minimum wages really “bite” only when they exceed a certain level. Or maybe employers have been reacting to them in ways not easily captured by wage data, such as by cutting benefits.

The push for higher state and local minimum wages shows no sign of abating, so no doubt we’ll learn even more in coming years about their trade-offs, or lack thereof.

Methodology: The effective minimum wage is the binding federal, state or local minimum wage weighted by the usual labor hours of minimum wage workers at nonfarm wage and salary jobs paid hourly. It includes all federal and state laws as well as 32 localities with separate ordinances whose geography we can identify in the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group. We exclude tipped occupations from this calculation using the definitions used by the Economic Policy Institute. We calculate median overall wages and average hourly earnings in the C.P.S. to be conceptually similar to average hourly earnings in the Current Employment Statistics survey. Inflation-adjusted series use the chained C.P.I.-U deflator, which is extended before 2000 using the deflator for personal consumption expenditures. This analysis uses data on local minimum wage ordinances from the U.C. Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education as well as from Kavya Vaghul and Ben Zipperer.

Ernie Tedeschi is an economist and head of fiscal analysis at Evercore ISI. He worked previously at the U.S. Treasury Department. The analysis here is solely his own. You can follow him on Twitter at @ernietedeschi.

A version of this article appears in print on April 29, 2019, Section A, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: Minimum Wage at Record High (Without Federal Help). Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

How climate change has intensified the deadly fires in Australia

The unprecedented conditions that have led to the devastating wildfires in Australia stem from a typical weather pattern that has been intensified by climate change. And the fire danger is expected to get worse in the future, CBS News meteorologist and climate specialist Jeff Berardelli said on "CBS This Morning" Friday.

More than 200 fires have burned roughly 12 million acres, forcing more than 100,000 residents and tourists to flee in one of the largest evacuations in Australia's history. At least 19 people have died. Navy ships helped evacuate hundreds of people from beaches along the country's southeastern coast.

With extreme heat and strong winds in the forecast, the country could see some of the worst fire weather of the season Saturday, Berardelli said.

"We're in a three-year drought in Australia," Berardelli said, adding that 2019 has been the hottest and driest year on record.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Australia hit 107 degrees for the average temperature, breaking a past record by 3 degrees. "As a meteorologist, that is remarkable, almost seems like it's not possible, but it happened," Berardelli said.

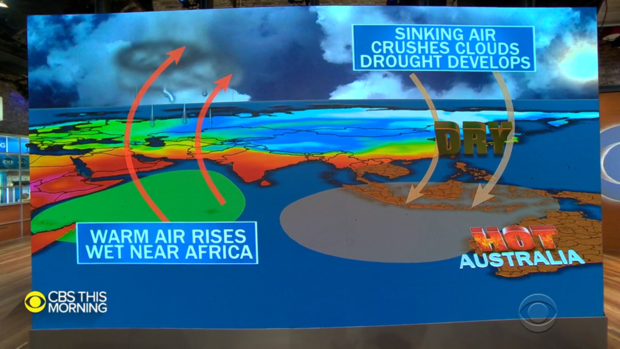

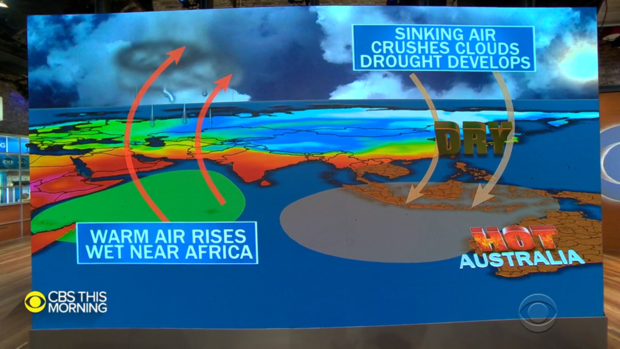

The drought is due in part to a typical weather pattern called the Indian Ocean Dipole.

"It's kind of like El Nino and La Nina. It goes back and forth over the course of years," Berardelli said. CBS NEWS

CBS NEWS

But this year, there has been a record Indian Ocean Dipole with warm water in the western part of the Indian Ocean and cooler-than-normal water in the eastern part, Berardelli said.

"So we end up with rising air over the western part of the ocean right near Africa. That causes rain. But sinking air, dry air in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean — that causes Indonesia and Australia to dry out," he said.

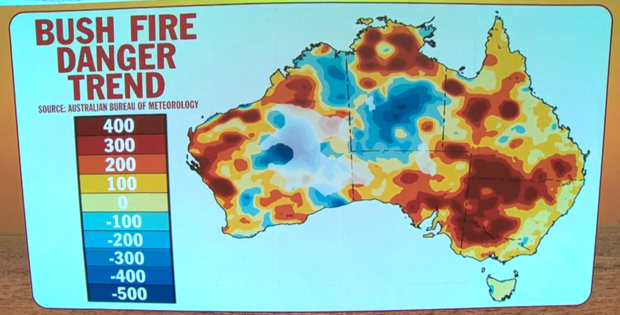

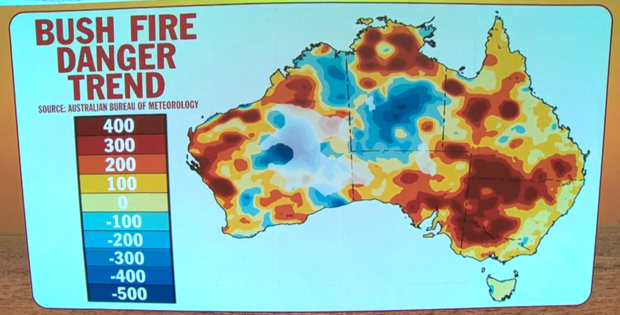

That extreme pattern has been made worse by warming temperatures, according to a study published in the journal Nature. The number of extreme heat days in Australia has increased from nearly zero in 1910 and 1920 to an average of about 15 per year now, and the average temperature of the country has increased by 3 degrees Fahrenheit over 100 years, Berardelli said. CBS NEWS

CBS NEWS

That increased heat dries out the soil and bush, increasing the fire danger, which has soared over the past 40 years, especially in the southeast portion of Australia.

"So this is a situation where climate change is kind of the background," Berardelli said. "When you have a natural pattern that's causing extreme fire danger, climate change spikes it, it enhances it, it turns extreme fire danger into catastrophic fire danger."

Berardelli added that the fire risk is expected to get worse in places like Australia.

"Places that get a lot of rain will get more rain, places that are dry like Australia will continue to get drier and drier. It will get worse there," he said. "In the United States, in places like California, not every year is a bad fire year, but when it's dry for a couple of years in a row, it will progressively get worse, and this will become kind of a new norm, but only worse."

© 2020 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The unprecedented conditions that have led to the devastating wildfires in Australia stem from a typical weather pattern that has been intensified by climate change. And the fire danger is expected to get worse in the future, CBS News meteorologist and climate specialist Jeff Berardelli said on "CBS This Morning" Friday.

More than 200 fires have burned roughly 12 million acres, forcing more than 100,000 residents and tourists to flee in one of the largest evacuations in Australia's history. At least 19 people have died. Navy ships helped evacuate hundreds of people from beaches along the country's southeastern coast.

With extreme heat and strong winds in the forecast, the country could see some of the worst fire weather of the season Saturday, Berardelli said.

"We're in a three-year drought in Australia," Berardelli said, adding that 2019 has been the hottest and driest year on record.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Australia hit 107 degrees for the average temperature, breaking a past record by 3 degrees. "As a meteorologist, that is remarkable, almost seems like it's not possible, but it happened," Berardelli said.

The drought is due in part to a typical weather pattern called the Indian Ocean Dipole.

"It's kind of like El Nino and La Nina. It goes back and forth over the course of years," Berardelli said.

CBS NEWS

CBS NEWSBut this year, there has been a record Indian Ocean Dipole with warm water in the western part of the Indian Ocean and cooler-than-normal water in the eastern part, Berardelli said.

"So we end up with rising air over the western part of the ocean right near Africa. That causes rain. But sinking air, dry air in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean — that causes Indonesia and Australia to dry out," he said.

That extreme pattern has been made worse by warming temperatures, according to a study published in the journal Nature. The number of extreme heat days in Australia has increased from nearly zero in 1910 and 1920 to an average of about 15 per year now, and the average temperature of the country has increased by 3 degrees Fahrenheit over 100 years, Berardelli said.

CBS NEWS

CBS NEWSThat increased heat dries out the soil and bush, increasing the fire danger, which has soared over the past 40 years, especially in the southeast portion of Australia.

"So this is a situation where climate change is kind of the background," Berardelli said. "When you have a natural pattern that's causing extreme fire danger, climate change spikes it, it enhances it, it turns extreme fire danger into catastrophic fire danger."

Berardelli added that the fire risk is expected to get worse in places like Australia.

"Places that get a lot of rain will get more rain, places that are dry like Australia will continue to get drier and drier. It will get worse there," he said. "In the United States, in places like California, not every year is a bad fire year, but when it's dry for a couple of years in a row, it will progressively get worse, and this will become kind of a new norm, but only worse."

© 2020 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

FAA checking potentially "catastrophic" issue with 737 Max wiring

BY KRIS VAN CLEAVE

JANUARY 6, 2020 / 11:39 AM / CBS NEWS

The Federal Aviation Administration is looking at a potentially "catastrophic" issue with wiring that helps control the tail of the 737 Max, CBS News has confirmed. The safety review was first reported by the New York Times and confirmed by Boeing officials.

It grew out of an FAA request to Boeing for an internal audit to confirm the company had accurately assessed the dangers of key systems in light of new assumptions about pilot response times to emergency situations.