Amazon has publicly promised to pay workers who test positive for or are quarantined because of the coronavirus, but some say they haven’t received that money.

“Don’t risk your life for $15 an hour. It’s not worth it. They don’t care."

Caroline O'Donovan BuzzFeed News Reporter

Last updated on May 5, 2020

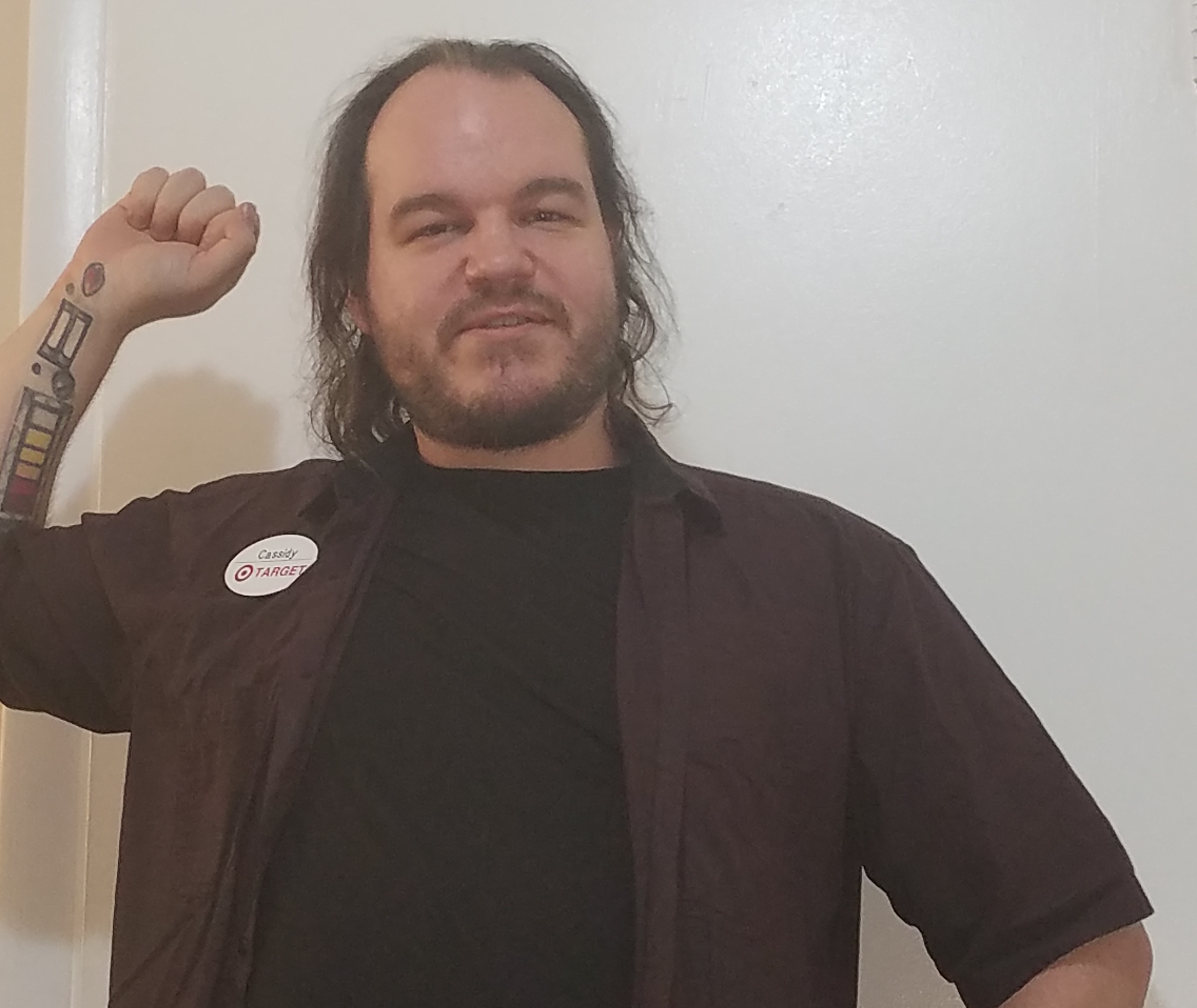

Thomas Pausuan SUPPLIED

Thomas Pausuan, a father of two who works at an Amazon warehouse outside Philadelphia, tested positive for the novel coronavirus in early April.

Under Amazon policy, Pausuan was eligible for paid sick leave. But Amazon stopped paying him the day after he got home from urgent care with a fever of 104, labored breathing, and a diagnosis of a potentially fatal disease.

It is the latest example of Amazon failing to promptly follow through on its promise to pay two weeks of wages to employees who are sick or quarantined. In some cases, workers have said they have consequently missed payments on their bills or had to borrow money from family or friends.

“We are working with employees on an individual basis and gathering the information we need to approve extra time off with pay for quarantine and/or diagnosis of COVID,” an Amazon spokesperson said in a statement. “With over 1,000 sites around the world, and so many measures and precautions rapidly rolled out over the past several weeks across safety, pay, benefits and operational processes, there may be instances where we don’t get it perfect, but can assure you that’s just what they are — exceptions.”

Amazon said it would deposit the money in Pausuan’s bank account after BuzzFeed News requested information about his case.

Amazon employees have complained that the department that handles sick leave payments was understaffed even before the coronavirus pandemic, and it has since been overwhelmed by the upswing in cases.

Pausuan started feeling sick in late March. He worried it could be the coronavirus, especially because he knew some of his coworkers at the Amazon warehouse where he worked had already tested positive.

He immediately isolated from his wife and children, but in their small apartment in South Philadelphia it was hard to maintain social distance. Before long, his family was sick too — although not as sick as he was.

“I had a fever of 104, and then the next day I started losing all smell and taste,” Pausuan said. “I felt very weak, and the whole body aches. It’s very hard to breathe. That’s the worst thing.”

On April 8, his test results confirmed what he’d known was almost certainly true: He had COVID-19.

As soon as Pausuan received his diagnosis, he sent documentation to Amazon human resources. The company had previously announced in early March that any employee who tested positive for the novel coronavirus would get up to two weeks of pay.

He expected to be paid as usual on his April 17 payday. After all, Amazon had repeatedly promised that workers who got sick would be paid. In fact, Jay Carney, senior vice president of global corporate affairs, said as much on CNN on April 17, the same day Pausuan was waiting in vain for the money to land in his account.

“We’re focusing our resources on helping our workers, giving them protective gear, giving them paid time off, increasing their pay,” Carney told CNN anchor Brianna Keilar.

"The only answer I got was 'Your case manager isn’t available right now.' How can someone be unavailable for a whole month?"

But the money never came.

"They gave me my case manager's extension, but whenever I tried to call that extension, the only answer I got was 'Your case manager isn’t available right now.' How can someone be unavailable for a whole month? It doesn't make sense,” Pausuan said on May 1.

He shared some of the correspondence between him and Amazon with BuzzFeed News.

“My name is Thomas T Pausuan I work for AcY1 amazon warehouse,” he emailed an HR associate on April 13. After testing positive for COVID-19, Pausuan explained, he requested paid medical leave, but his request wasn’t approved. “I hope I get all help fast because I’m test positive my wife also have to quarantine herself[. N]o one can go to work and there is no paycheck.”

Pausuan said this email and subsequent ones went unanswered.

Four days later, he wrote to Amazon’s disability and leave team: “According to Amazon Covid-19 policy I was tested positive and never get paid sick leave why? It’s been 2 weeks I stay home isolate myself. I didn’t get paid why?”

And on May 1, he wrote again: “I still didn’t hear nothing from my case manager. [...] I need money[.] I have a family to feed. I hope some one hear my voice.”

Pausuan said he received a federal stimulus check in April, which helped him cover credit card payments, car payments, car insurance, and rent. “That’s how we survive until now,” he said on Friday.

Like other Amazon employees who spoke with BuzzFeed News, Pausuan said when he called the employee resource center he was told he’d hear back within a few days. They never called.

“Almost every day, I call them to prove my case and escalate my case so I can get paid. I tried so many times. Believe me,” he said. “The only answer I get is ‘someone will call you in two business days.’ And then, [after] two business days, they don’t call you. For one month.”

Finally, last week, Pausuan reached out to BuzzFeed News, which has repeatedly written about workers who are not being paid despite having symptoms of COVID-19 or being instructed to quarantine by a doctor.

Under Amazon policy, Pausuan was eligible for paid sick leave. But Amazon stopped paying him the day after he got home from urgent care with a fever of 104, labored breathing, and a diagnosis of a potentially fatal disease.

It is the latest example of Amazon failing to promptly follow through on its promise to pay two weeks of wages to employees who are sick or quarantined. In some cases, workers have said they have consequently missed payments on their bills or had to borrow money from family or friends.

“We are working with employees on an individual basis and gathering the information we need to approve extra time off with pay for quarantine and/or diagnosis of COVID,” an Amazon spokesperson said in a statement. “With over 1,000 sites around the world, and so many measures and precautions rapidly rolled out over the past several weeks across safety, pay, benefits and operational processes, there may be instances where we don’t get it perfect, but can assure you that’s just what they are — exceptions.”

Amazon said it would deposit the money in Pausuan’s bank account after BuzzFeed News requested information about his case.

Amazon employees have complained that the department that handles sick leave payments was understaffed even before the coronavirus pandemic, and it has since been overwhelmed by the upswing in cases.

Pausuan started feeling sick in late March. He worried it could be the coronavirus, especially because he knew some of his coworkers at the Amazon warehouse where he worked had already tested positive.

He immediately isolated from his wife and children, but in their small apartment in South Philadelphia it was hard to maintain social distance. Before long, his family was sick too — although not as sick as he was.

“I had a fever of 104, and then the next day I started losing all smell and taste,” Pausuan said. “I felt very weak, and the whole body aches. It’s very hard to breathe. That’s the worst thing.”

On April 8, his test results confirmed what he’d known was almost certainly true: He had COVID-19.

As soon as Pausuan received his diagnosis, he sent documentation to Amazon human resources. The company had previously announced in early March that any employee who tested positive for the novel coronavirus would get up to two weeks of pay.

He expected to be paid as usual on his April 17 payday. After all, Amazon had repeatedly promised that workers who got sick would be paid. In fact, Jay Carney, senior vice president of global corporate affairs, said as much on CNN on April 17, the same day Pausuan was waiting in vain for the money to land in his account.

“We’re focusing our resources on helping our workers, giving them protective gear, giving them paid time off, increasing their pay,” Carney told CNN anchor Brianna Keilar.

"The only answer I got was 'Your case manager isn’t available right now.' How can someone be unavailable for a whole month?"

But the money never came.

"They gave me my case manager's extension, but whenever I tried to call that extension, the only answer I got was 'Your case manager isn’t available right now.' How can someone be unavailable for a whole month? It doesn't make sense,” Pausuan said on May 1.

He shared some of the correspondence between him and Amazon with BuzzFeed News.

“My name is Thomas T Pausuan I work for AcY1 amazon warehouse,” he emailed an HR associate on April 13. After testing positive for COVID-19, Pausuan explained, he requested paid medical leave, but his request wasn’t approved. “I hope I get all help fast because I’m test positive my wife also have to quarantine herself[. N]o one can go to work and there is no paycheck.”

Pausuan said this email and subsequent ones went unanswered.

Four days later, he wrote to Amazon’s disability and leave team: “According to Amazon Covid-19 policy I was tested positive and never get paid sick leave why? It’s been 2 weeks I stay home isolate myself. I didn’t get paid why?”

And on May 1, he wrote again: “I still didn’t hear nothing from my case manager. [...] I need money[.] I have a family to feed. I hope some one hear my voice.”

Pausuan said he received a federal stimulus check in April, which helped him cover credit card payments, car payments, car insurance, and rent. “That’s how we survive until now,” he said on Friday.

Like other Amazon employees who spoke with BuzzFeed News, Pausuan said when he called the employee resource center he was told he’d hear back within a few days. They never called.

“Almost every day, I call them to prove my case and escalate my case so I can get paid. I tried so many times. Believe me,” he said. “The only answer I get is ‘someone will call you in two business days.’ And then, [after] two business days, they don’t call you. For one month.”

Finally, last week, Pausuan reached out to BuzzFeed News, which has repeatedly written about workers who are not being paid despite having symptoms of COVID-19 or being instructed to quarantine by a doctor.

In April, BuzzFeed News reported that at least eight employees who had been told to stay home by doctors hadn’t received payment as promised.

When asked about those cases, the company publicly promised employees who had been quarantined by a doctor would eventually be paid.

Nearly four weeks later, four of those employees, most of whom asked not to be named out of fear of retribution, said they’ve since received some payment from Amazon, though most said they had received less money than they thought they were owed. An employee on short-term disability leave receives just 60% of their usual paychecks.

Two more could not be reached this week by BuzzFeed News.

And two said they have still received nothing.

“Don’t risk your life for $15 an hour. It’s not worth it. They don’t care."

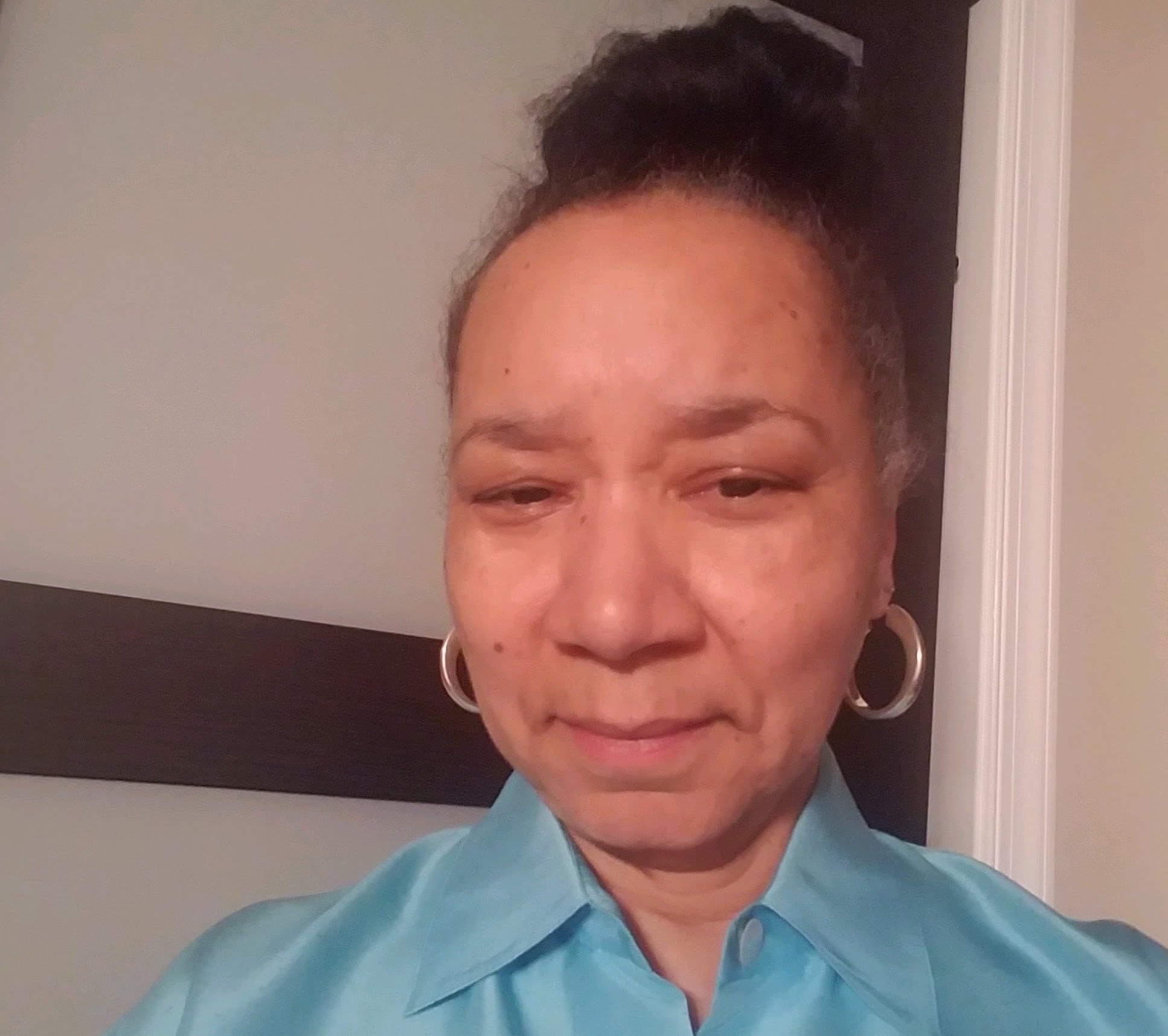

One of those workers, a single mother in Missouri who requested anonymity to protect her job, said Amazon HR told her she was eligible for two weeks of pay and could apply for short-term disability thereafter. She was eventually diagnosed with pneumonia but tested negative for the coronavirus. She has not been paid.

“I’m just lucky I live in a very generous community who has stepped forward and helped feed me and my family,” she said.

During the pandemic, Amazon sales have soared as people stay home and avoid shopping in brick-and-mortar stores. On an earnings call last week, executives said the company is spending that additional revenue on its response to the coronavirus, including protections and higher wages for its warehouse staff. The company also said it’s hired 175,000 new staffers in its logistics and delivery network since March. Many of those new hires, said Brian T. Olsavsky, Amazon's chief financial officer, during the call, “were displaced from other jobs in the economy.”

Pausuan said the way he has been treated has made him feel like a worn-out part that can easily be replaced by a newer model.

“Don’t risk your life for $15 an hour. It’s not worth it. They don’t care,” he continued. “Once someone’s sick, they hire two people. They don’t care about the sick one, because they can hire back as many as they want.”

When asked about those cases, the company publicly promised employees who had been quarantined by a doctor would eventually be paid.

Nearly four weeks later, four of those employees, most of whom asked not to be named out of fear of retribution, said they’ve since received some payment from Amazon, though most said they had received less money than they thought they were owed. An employee on short-term disability leave receives just 60% of their usual paychecks.

Two more could not be reached this week by BuzzFeed News.

And two said they have still received nothing.

“Don’t risk your life for $15 an hour. It’s not worth it. They don’t care."

One of those workers, a single mother in Missouri who requested anonymity to protect her job, said Amazon HR told her she was eligible for two weeks of pay and could apply for short-term disability thereafter. She was eventually diagnosed with pneumonia but tested negative for the coronavirus. She has not been paid.

“I’m just lucky I live in a very generous community who has stepped forward and helped feed me and my family,” she said.

During the pandemic, Amazon sales have soared as people stay home and avoid shopping in brick-and-mortar stores. On an earnings call last week, executives said the company is spending that additional revenue on its response to the coronavirus, including protections and higher wages for its warehouse staff. The company also said it’s hired 175,000 new staffers in its logistics and delivery network since March. Many of those new hires, said Brian T. Olsavsky, Amazon's chief financial officer, during the call, “were displaced from other jobs in the economy.”

Pausuan said the way he has been treated has made him feel like a worn-out part that can easily be replaced by a newer model.

“Don’t risk your life for $15 an hour. It’s not worth it. They don’t care,” he continued. “Once someone’s sick, they hire two people. They don’t care about the sick one, because they can hire back as many as they want.”

Caroline O'Donovan · April 18, 2020

Caroline O'Donovan · April 14, 2020

Caroline O'Donovan · April 11, 2020

TOPICS IN THIS ARTICLE

Amazon

Caroline O'Donovan is a senior technology reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

TOPICS IN THIS ARTICLE

Amazon

Caroline O'Donovan is a senior technology reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.