Glenda Jackson: ‘I’m an antisocial socialist’

Rich Pelley

Glenda Jackson: ‘I am not very good at dressing up. I don’t really like parties.’

Photograph: Anton Corbijn/Trunk Archive

Glenda Jackson doesn’t much like going out, but to save the UK’s arts industry, the actor, former MP and slightly terrifying national treasure will consider it…

Published on Sun 26 Jul 2020

“Don’t be ridiculous,” barks Glenda Jackson down the phone. “Are you kidding me?”

Oh dear. You don’t want to get on the wrong side of Glenda Jackson. The 84-year-old double Oscar-winning actor and ex-MP is the national treasure of national treasures; as renowned for speaking her mind as she is for airing her politics. Indeed, as a Labour MP she famously threatened to challenge Tony Blair if he didn’t resign over the Hutton inquiry into Iraq. So she’s hardly likely to take any nonsense from some scruffy journalist who has just asked her if she would consider a return to politics.

“I’m 84 years old. You think I’ve got the energy to go pounding around the pavements again?” she says. How about if they just instantly promoted her to prime minister, I wonder, out loud, by accident, with immediate regret.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake. I took being an MP very seriously. Questions like that don’t sit well with me.”

Insubordinate questions aside, Glenda Jackson is lovely; like any octogenarian who has spent their career in the public eye, she dishes out as good as she gets. She doesn’t do Zoom, and sensibly isn’t taking in visitors at the moment, but otherwise she’s more than happy to accommodate. (“This is your interview, my dear,” she reassures. “You choose what we talk about.”) She’s Glenda all over, but the only Glenda I get to appreciate today is that voice: velvet, austere and with the throaty rasp of smoking a lifetime’s stash of fags.

We’re speaking today because Jackson is back on our screens for the first time since 1992, and back in the running for awards in spite of the fact that she’s already won them all, from Emmys, Golden Globes and Oscars to Tony Awards. (“I’m not ungrateful,” she says nonchalantly, “but that isn’t what you work for. I was just grateful for getting the job. The idea of something on top was way down the list.”)

Glenda Jackson doesn’t much like going out, but to save the UK’s arts industry, the actor, former MP and slightly terrifying national treasure will consider it…

Published on Sun 26 Jul 2020

“Don’t be ridiculous,” barks Glenda Jackson down the phone. “Are you kidding me?”

Oh dear. You don’t want to get on the wrong side of Glenda Jackson. The 84-year-old double Oscar-winning actor and ex-MP is the national treasure of national treasures; as renowned for speaking her mind as she is for airing her politics. Indeed, as a Labour MP she famously threatened to challenge Tony Blair if he didn’t resign over the Hutton inquiry into Iraq. So she’s hardly likely to take any nonsense from some scruffy journalist who has just asked her if she would consider a return to politics.

“I’m 84 years old. You think I’ve got the energy to go pounding around the pavements again?” she says. How about if they just instantly promoted her to prime minister, I wonder, out loud, by accident, with immediate regret.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake. I took being an MP very seriously. Questions like that don’t sit well with me.”

Insubordinate questions aside, Glenda Jackson is lovely; like any octogenarian who has spent their career in the public eye, she dishes out as good as she gets. She doesn’t do Zoom, and sensibly isn’t taking in visitors at the moment, but otherwise she’s more than happy to accommodate. (“This is your interview, my dear,” she reassures. “You choose what we talk about.”) She’s Glenda all over, but the only Glenda I get to appreciate today is that voice: velvet, austere and with the throaty rasp of smoking a lifetime’s stash of fags.

We’re speaking today because Jackson is back on our screens for the first time since 1992, and back in the running for awards in spite of the fact that she’s already won them all, from Emmys, Golden Globes and Oscars to Tony Awards. (“I’m not ungrateful,” she says nonchalantly, “but that isn’t what you work for. I was just grateful for getting the job. The idea of something on top was way down the list.”)

Vote winner: at a Labour Party meeting with Gordon Brown in 2010. Photograph: Alan Davidson/Rex/Shutterstock

This time she’s up for a TV Bafta for the BBC drama Elizabeth is Missing, screened last Christmas and based on the 2014 novel by Emma Healey. The Guardian awarded it five stars, praising Jackson’s “magnificent form in a poignant murder mystery that doubles as a study of the sorrows of dementia.” Jackson herself has been nominated for best actress at the ceremony, which takes place on 31 July. (“I’ll be watching in my living room, on Zoom, or whatever it’s called…”)

Is she enjoying the limelight again?

“I mean, there’s very little limelight in my small flat. I assure you of that.”

Jackson lives in a basement granny flat in Blackheath. Her 51-year-old son – Mail on Sunday columnist Dan Hodges – lives upstairs with his wife and 11-year-old son, Jackson’s only grandchild.

“I haven’t been out of my front door for three months,” she says. “Fortunately, my flat is garden level. The sun is shining. The rest of my family live upstairs, so I do have people looking after me, which is nice. I have lost all track of time. Time is an endless river, but I never know which day it is. It was my birthday in May. My grandson came downstairs and said, ‘Happy birthday’. I didn’t know it was my birthday. I’d completely forgotten. But then I’ve never been a birthday person.”

And how does she think the government has been coping with this terrible pandemic?

“I mean, they’re not, but you wouldn’t expect me to have any other reaction to a Conservative government. But in fairness, this is such an extraordinary interruption to life that I think we can be critical when we should be, but supportive when we have to be. I think Keir [Starmer] is doing very well. But at the moment, party politics are way down the level of national concern.”

This time she’s up for a TV Bafta for the BBC drama Elizabeth is Missing, screened last Christmas and based on the 2014 novel by Emma Healey. The Guardian awarded it five stars, praising Jackson’s “magnificent form in a poignant murder mystery that doubles as a study of the sorrows of dementia.” Jackson herself has been nominated for best actress at the ceremony, which takes place on 31 July. (“I’ll be watching in my living room, on Zoom, or whatever it’s called…”)

Is she enjoying the limelight again?

“I mean, there’s very little limelight in my small flat. I assure you of that.”

Jackson lives in a basement granny flat in Blackheath. Her 51-year-old son – Mail on Sunday columnist Dan Hodges – lives upstairs with his wife and 11-year-old son, Jackson’s only grandchild.

“I haven’t been out of my front door for three months,” she says. “Fortunately, my flat is garden level. The sun is shining. The rest of my family live upstairs, so I do have people looking after me, which is nice. I have lost all track of time. Time is an endless river, but I never know which day it is. It was my birthday in May. My grandson came downstairs and said, ‘Happy birthday’. I didn’t know it was my birthday. I’d completely forgotten. But then I’ve never been a birthday person.”

And how does she think the government has been coping with this terrible pandemic?

“I mean, they’re not, but you wouldn’t expect me to have any other reaction to a Conservative government. But in fairness, this is such an extraordinary interruption to life that I think we can be critical when we should be, but supportive when we have to be. I think Keir [Starmer] is doing very well. But at the moment, party politics are way down the level of national concern.”

The view from here: with her husband Roy Hodges 1971. She had just been awarded an Academy Award for her role as Gudrun in Women in Love. Photograph: Joe Bangay/Getty Images

The major political event since Jackson’s political retirement has of course been Brexit, to which the conversation naturally flows. Where did she stand?

“Well, I’m a Remainer,” she says. “I went to bed the night of the referendum hearing that the verdict was going to be remain. I woke up in the morning to discover we were coming out. I said to my daughter-in-law, ‘We’re going to have to emigrate to Scotland!’”

Only 27% of 18 to 24-year-olds who voted, voted to leave. But 60% of over-65s who voted, voted to leave. Does Jackson have any theories on why Brexit was so successful at securing the so-called grey vote?

“Was it really 60%?” she queries. “I can certainly see how it was a generational thing, looking through rose-tinted spectacles, saying, ‘We can be an empire again’. But do you seriously think Canada, New Zealand and Australia are going to say, ‘Please govern us again’? I think most young people are still shocked at the idea of coming out of Europe. Negotiations are still ongoing. We still don’t know what kind of deal we’re going to get and we won’t until the pandemic stops pushing it off the front pages.”

As part of its pandemic measures, the government earlier this month announced its £1.57bn investment to protect Britain’s cultural, arts and heritage institutions, having left much of the industry up the proverbial creak since March. What does Jackson say to this scheme?

The major political event since Jackson’s political retirement has of course been Brexit, to which the conversation naturally flows. Where did she stand?

“Well, I’m a Remainer,” she says. “I went to bed the night of the referendum hearing that the verdict was going to be remain. I woke up in the morning to discover we were coming out. I said to my daughter-in-law, ‘We’re going to have to emigrate to Scotland!’”

Only 27% of 18 to 24-year-olds who voted, voted to leave. But 60% of over-65s who voted, voted to leave. Does Jackson have any theories on why Brexit was so successful at securing the so-called grey vote?

“Was it really 60%?” she queries. “I can certainly see how it was a generational thing, looking through rose-tinted spectacles, saying, ‘We can be an empire again’. But do you seriously think Canada, New Zealand and Australia are going to say, ‘Please govern us again’? I think most young people are still shocked at the idea of coming out of Europe. Negotiations are still ongoing. We still don’t know what kind of deal we’re going to get and we won’t until the pandemic stops pushing it off the front pages.”

As part of its pandemic measures, the government earlier this month announced its £1.57bn investment to protect Britain’s cultural, arts and heritage institutions, having left much of the industry up the proverbial creak since March. What does Jackson say to this scheme?

Long to reign over us: as Queen Elizabeth I in Mary, Queen of Scots in 1971. Photograph: Moviestore/Rex/Shutterstock

“I say, ‘Thank you very much indeed.’ But the problem, certainly for the performing arts, is that generating money is vital. The problem remains: will audiences be confident enough to come back? The idea that performances now can take place outdoors is very positive. We’ve always had outdoor summer performances, even when it pours with rain. It’s good, but we’ll have to wait and see.”

Considering that the arts is Britain’s second biggest economy after finance, is £1.57bn enough? By comparison, the government’s furlough scheme is thought to have cost £14bn a month since March.

“The word ‘enough’ is meaningless, really,” Jackson continues. “Some productions require a great deal of money. Others can be very small. But it’s good to know that at least the validity of the arts, of our culture has been acknowledged and there is money to keep at least several arms and legs afloat. But I go back to my previous point. When will we, as people, feel confident enough to sit in theatres and concert halls? We’re still in this uncertain area. Have we actually crushed this pandemic? Or is a second spike going to come next week?”

So how would she feel about venturing out of the house for the first time in three months to put her Most Excellent Order of the British Empire bum on seat?

“As a member of the audience? I would seriously think about it. I was thinking about this earlier and wondered if it would be possible to stage something where you could see the stage, but any potential germs might be prevented by… a very fine net or something. I know it sounds ridiculous… Fortunately, we’re talking about the acknowledged creative aspect of a society. So people will come up with ideas.”

Anyway, she doesn’t particularly like going out. “I’m not good at dressing up. I don’t particularly like going out to parties. I think I’m an antisocial socialist, actually.”

So, not a big schmoozer? “No. I’m no good at it. I can’t do it. It’s just not my style. There’s always the element that you have to sell the product. But for me, it’s only the work that’s interesting.”

“I say, ‘Thank you very much indeed.’ But the problem, certainly for the performing arts, is that generating money is vital. The problem remains: will audiences be confident enough to come back? The idea that performances now can take place outdoors is very positive. We’ve always had outdoor summer performances, even when it pours with rain. It’s good, but we’ll have to wait and see.”

Considering that the arts is Britain’s second biggest economy after finance, is £1.57bn enough? By comparison, the government’s furlough scheme is thought to have cost £14bn a month since March.

“The word ‘enough’ is meaningless, really,” Jackson continues. “Some productions require a great deal of money. Others can be very small. But it’s good to know that at least the validity of the arts, of our culture has been acknowledged and there is money to keep at least several arms and legs afloat. But I go back to my previous point. When will we, as people, feel confident enough to sit in theatres and concert halls? We’re still in this uncertain area. Have we actually crushed this pandemic? Or is a second spike going to come next week?”

So how would she feel about venturing out of the house for the first time in three months to put her Most Excellent Order of the British Empire bum on seat?

“As a member of the audience? I would seriously think about it. I was thinking about this earlier and wondered if it would be possible to stage something where you could see the stage, but any potential germs might be prevented by… a very fine net or something. I know it sounds ridiculous… Fortunately, we’re talking about the acknowledged creative aspect of a society. So people will come up with ideas.”

Anyway, she doesn’t particularly like going out. “I’m not good at dressing up. I don’t particularly like going out to parties. I think I’m an antisocial socialist, actually.”

So, not a big schmoozer? “No. I’m no good at it. I can’t do it. It’s just not my style. There’s always the element that you have to sell the product. But for me, it’s only the work that’s interesting.”

To play the king: as Lear at the Old Vic with Rhys Ifans as Fool and directed by Deborah Warner. Photograph: Tristram Kenton/The Guardian

Isn’t schmoozing just acting? Can’t she just act schmoozey? “Oh, come on. That isn’t what it’s about. The demands are very different.”

Jackson found fame in 1970s Academy Award-winning romantic dramas Women in Love and A Touch of Class, then quit a stellar acting career for politics when she was elected Labour MP for Hampstead and Highgate in 1992. She was junior transport minister from 1997 to 1999 and stood down in the 2015 general election, two days before her 79th birthday.

The next year, she returned to the stage for the first time in 25 years, as King Lear at the Old Vic and later Broadway. Her performance was touted as “magnificent” and Jackson was nominated for an Olivier. Was she confident in returning to acting? What if she’d forgotten how to act?

“That’s what someone said to me when I was doing Lear at the Old Vic,” she says. “I was talking to a friend and I said, ‘My God, I might have forgotten.’ And she said, ‘It’s like riding a bike. You never forget.’”

Jackson was cast sex-blind as King Lear because King Lear is, more traditionally – and definitely according to Shakespeare – a bloke. Sir Ian McKellen (age 81) has just been cast as Hamlet (age 30) in a similar age-blind role.

“Well, that’s nice, isn’t it? If we’re all living longer, that includes actors as well, I hope,” says Jackson. “It will be interesting to see what he does with it.”

You’ve done sex-blind. Could you do age-blind, I ask? Could you be a Juliet?

“Are you kidding me?” laughs Jackson. “Come on! One of the things I’ve found most curious – given we’re not equal by any means as far as women in the world are concerned – is that contemporary dramatists still don’t find us interesting. Very few contemporary dramatists place a woman as the central dramatic. And I find that bizarre. I’ve been banging on about it for a very long time, but nobody takes any notice.”

But you’re Glenda Jackson! They should listen to your every word!

“Oh, come off it!”

How about Margaret Thatcher? Could you play her, um, politics-blind?

“I would find it very hard. I’ve always tried to abide by an unbreakable rule that you have to look at the world through the eyes of whoever you are playing. And I would find it very, very hard to see the world that Thatcher wanted us to inhabit.”

She’s played Elizabeth I, a role for which she famously shaved her head. Could she play Queen Elizabeth Version 2.0?

“Oh, well anybody can play the Queen. I mean, God, if ever a woman’s kept herself to herself, it’s the Queen. Who knows what she’s like? You know what she’s like as the Queen. What’s she like as a person? That is one of the best kept secrets in the world.”

Does Jackson watch her own TV shows and films?

“No.”

What happens if one comes on telly, would she change the channel?

“Well, it would be on very late at night, wouldn’t it? I’d be in bed and fast asleep.”

Is she critical of her own performances?

“I certainly don’t enjoy them. My reaction is completely subjective. I think, ‘Why did you choose to do that? Why didn’t you do something different there?’ But it’s all too late. It’s pretty much part of the sadomasochistic streak, which I think is in all actors.”

Isn’t schmoozing just acting? Can’t she just act schmoozey? “Oh, come on. That isn’t what it’s about. The demands are very different.”

Jackson found fame in 1970s Academy Award-winning romantic dramas Women in Love and A Touch of Class, then quit a stellar acting career for politics when she was elected Labour MP for Hampstead and Highgate in 1992. She was junior transport minister from 1997 to 1999 and stood down in the 2015 general election, two days before her 79th birthday.

The next year, she returned to the stage for the first time in 25 years, as King Lear at the Old Vic and later Broadway. Her performance was touted as “magnificent” and Jackson was nominated for an Olivier. Was she confident in returning to acting? What if she’d forgotten how to act?

“That’s what someone said to me when I was doing Lear at the Old Vic,” she says. “I was talking to a friend and I said, ‘My God, I might have forgotten.’ And she said, ‘It’s like riding a bike. You never forget.’”

Jackson was cast sex-blind as King Lear because King Lear is, more traditionally – and definitely according to Shakespeare – a bloke. Sir Ian McKellen (age 81) has just been cast as Hamlet (age 30) in a similar age-blind role.

“Well, that’s nice, isn’t it? If we’re all living longer, that includes actors as well, I hope,” says Jackson. “It will be interesting to see what he does with it.”

You’ve done sex-blind. Could you do age-blind, I ask? Could you be a Juliet?

“Are you kidding me?” laughs Jackson. “Come on! One of the things I’ve found most curious – given we’re not equal by any means as far as women in the world are concerned – is that contemporary dramatists still don’t find us interesting. Very few contemporary dramatists place a woman as the central dramatic. And I find that bizarre. I’ve been banging on about it for a very long time, but nobody takes any notice.”

But you’re Glenda Jackson! They should listen to your every word!

“Oh, come off it!”

How about Margaret Thatcher? Could you play her, um, politics-blind?

“I would find it very hard. I’ve always tried to abide by an unbreakable rule that you have to look at the world through the eyes of whoever you are playing. And I would find it very, very hard to see the world that Thatcher wanted us to inhabit.”

She’s played Elizabeth I, a role for which she famously shaved her head. Could she play Queen Elizabeth Version 2.0?

“Oh, well anybody can play the Queen. I mean, God, if ever a woman’s kept herself to herself, it’s the Queen. Who knows what she’s like? You know what she’s like as the Queen. What’s she like as a person? That is one of the best kept secrets in the world.”

Does Jackson watch her own TV shows and films?

“No.”

What happens if one comes on telly, would she change the channel?

“Well, it would be on very late at night, wouldn’t it? I’d be in bed and fast asleep.”

Is she critical of her own performances?

“I certainly don’t enjoy them. My reaction is completely subjective. I think, ‘Why did you choose to do that? Why didn’t you do something different there?’ But it’s all too late. It’s pretty much part of the sadomasochistic streak, which I think is in all actors.”

‘People have said that the care sector should be equated with the NHS’: starring in Elizabeth is Missing which deals with the challenges of living with Alzheimer’s. Photograph: Marsaili Mainz/Acorn TV

In Elizabeth is Missing, Jackson plays a widowed grandmother living with Alzheimer’s – something she thinks we ignore at our peril. “Despite the pandemic, we are – along with all other western democracies – living longer. And the big black hole that no one really has examined – is, how do we actually pay for those extra years when people may not have a family to support their inability to look after themselves, because of Alzheimer’s and dementia?

“We need to have that discussion: how do we pay for it? We’re beginning to see the first ripples in what will be a fairly big stream of how to provide the requisite care as a society. But this is not something that can be solved by individual practices. It is something that we, as a society, have to put on the table and think about seriously. For example, people have said that the care sector should be equated with the NHS. This is something that has to be looked at.”

I wonder if Jackson feels vulnerable herself? Does she feel her own immortality?

“Well, by virtue of my age and of the time we’re living in, I mean, of course one does. I’m not overtly religious, but when things get bad, I’m constantly calling on God. I’m grateful for the other dimensions that are there for all of us. I do believe that we’re more than flesh, blood and stone. I was partially raised as a Welsh Presbyterian and that runs quite deep. I do have a spiritual side.”

Has she ever met anyone else called Glenda?

“I did, actually. A woman came up to me. It was years ago. My mother was torn between two Hollywood stars – Glenda Farrell and Shirley Temple. I think I’m quite grateful she opted for Ms Farrell.

And has she taken up any bonkers hobbies during lockdown, to help pass the time?”

“No,” she chuckles. “But I do have the tidiest knicker drawer in the world.”

Elizabeth is Missing is available to stream on Acorn TV from 31 July

An interview with Glenda Jackson – archive, 1969

28 November 1969 While starring as Gudrun in Ken Russell’s Women in Love should have made here instantly recognisable, Jackson maintains her anonymity is safe

In Elizabeth is Missing, Jackson plays a widowed grandmother living with Alzheimer’s – something she thinks we ignore at our peril. “Despite the pandemic, we are – along with all other western democracies – living longer. And the big black hole that no one really has examined – is, how do we actually pay for those extra years when people may not have a family to support their inability to look after themselves, because of Alzheimer’s and dementia?

“We need to have that discussion: how do we pay for it? We’re beginning to see the first ripples in what will be a fairly big stream of how to provide the requisite care as a society. But this is not something that can be solved by individual practices. It is something that we, as a society, have to put on the table and think about seriously. For example, people have said that the care sector should be equated with the NHS. This is something that has to be looked at.”

I wonder if Jackson feels vulnerable herself? Does she feel her own immortality?

“Well, by virtue of my age and of the time we’re living in, I mean, of course one does. I’m not overtly religious, but when things get bad, I’m constantly calling on God. I’m grateful for the other dimensions that are there for all of us. I do believe that we’re more than flesh, blood and stone. I was partially raised as a Welsh Presbyterian and that runs quite deep. I do have a spiritual side.”

Has she ever met anyone else called Glenda?

“I did, actually. A woman came up to me. It was years ago. My mother was torn between two Hollywood stars – Glenda Farrell and Shirley Temple. I think I’m quite grateful she opted for Ms Farrell.

And has she taken up any bonkers hobbies during lockdown, to help pass the time?”

“No,” she chuckles. “But I do have the tidiest knicker drawer in the world.”

Elizabeth is Missing is available to stream on Acorn TV from 31 July

An interview with Glenda Jackson – archive, 1969

28 November 1969 While starring as Gudrun in Ken Russell’s Women in Love should have made here instantly recognisable, Jackson maintains her anonymity is safe

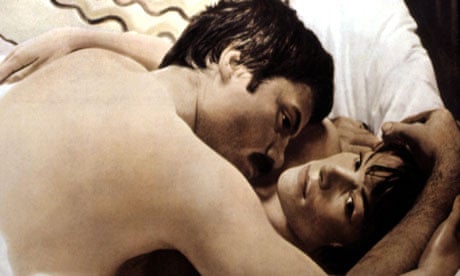

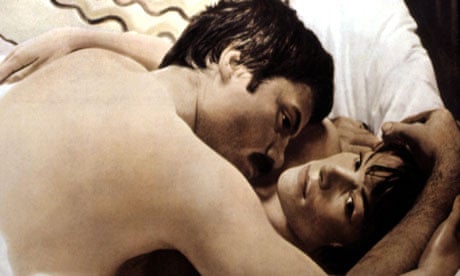

Glenda Jackson in Women in Love, 1969. Photograph: Everett/REX Shutterstock

Catherine Stott

Published onTue 28 Nov 2017 05.00 GMT

Glenda Jackson has a face which, while not actually anonymous, can change so much from one day to the next, from one emotion to another, as to be barely recognisable. Indeed no one ever has recognised her, for which fact she is enormously grateful. It would seem likely to anyone else that Miss Jackson cannot fail to be instantly recognisable henceforth, after the marvellous reviews she has collected for her performance as Gudrun in Women in Love, but she thankfully maintains that her precious anonymity is safe.

For several years she has been an actor’s, critic’s, and director’s actress; extremely diligent and professional on the job, but having a real horror of the glossy accompaniments to the success in her field. The only time she thinks about acting is when she is doing it and she divides her life rigidly into “work” and “home” – “an ordinary person leading a non public life” she calls herself. Asked to give a rundown of her acting career, she disposes of 13 years’ work in about 20 seconds, where far less talented actresses would take a good two hours.

Glenda Jackson on her scary reputation: ‘I’ve never understood the fear thing’

ead more

She says that she had six lean years and seven where things were getting better and she was always in work. She first came to notice after playing Charlotte Corday in the Peter Brook production of The Marat/Sade.

She explains her workmanlike attitude: “The thing about acting is that you start out looking for work and that takes you three quarters of your time and the quality and size of it are immaterial – all you want to do is work. Then you work more regularly and perhaps do one thing which attracts notice and brings more work. The only people I ever meet are people involved with the work, never anybody outside who says, ‘Gosh, aren’t you Glenda Jackson?’ So the so-called acclaim is merely some thing you read about. It doesn’t touch me personally.

I’m quite sure I’ll never be recognised anyway because I never look outside like I look in anything I act in. I go out looking absolutely dreadful.” (She pulls an ugly face to demonstrate and for a moment it is hard to see how “Harper’s” once wanted to include her in their list of Most Beautiful Women.)

Catherine Stott

Published onTue 28 Nov 2017 05.00 GMT

Glenda Jackson has a face which, while not actually anonymous, can change so much from one day to the next, from one emotion to another, as to be barely recognisable. Indeed no one ever has recognised her, for which fact she is enormously grateful. It would seem likely to anyone else that Miss Jackson cannot fail to be instantly recognisable henceforth, after the marvellous reviews she has collected for her performance as Gudrun in Women in Love, but she thankfully maintains that her precious anonymity is safe.

For several years she has been an actor’s, critic’s, and director’s actress; extremely diligent and professional on the job, but having a real horror of the glossy accompaniments to the success in her field. The only time she thinks about acting is when she is doing it and she divides her life rigidly into “work” and “home” – “an ordinary person leading a non public life” she calls herself. Asked to give a rundown of her acting career, she disposes of 13 years’ work in about 20 seconds, where far less talented actresses would take a good two hours.

Glenda Jackson on her scary reputation: ‘I’ve never understood the fear thing’

ead more

She says that she had six lean years and seven where things were getting better and she was always in work. She first came to notice after playing Charlotte Corday in the Peter Brook production of The Marat/Sade.

She explains her workmanlike attitude: “The thing about acting is that you start out looking for work and that takes you three quarters of your time and the quality and size of it are immaterial – all you want to do is work. Then you work more regularly and perhaps do one thing which attracts notice and brings more work. The only people I ever meet are people involved with the work, never anybody outside who says, ‘Gosh, aren’t you Glenda Jackson?’ So the so-called acclaim is merely some thing you read about. It doesn’t touch me personally.

I’m quite sure I’ll never be recognised anyway because I never look outside like I look in anything I act in. I go out looking absolutely dreadful.” (She pulls an ugly face to demonstrate and for a moment it is hard to see how “Harper’s” once wanted to include her in their list of Most Beautiful Women.)

Oliver Reed, Glenda Jackson, Alan Bates, Jennie Linden and Eleanor Bron in a scene of Ken Russell’s film Women in Love. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/UNITED ARTISTS

Women in Love is Glenda Jackson’s first film to have an automatic release. By the time she finished it she was six months pregnant. Now she is playing the mad wife of Tchaikovsky, again in a Ken Russell film, and next year expects to play the Dorothy Tutin part in The Devils – again for Ken Russell. Being a rather severe artist herself, she says characteristically that “this will be a very good thing for Ken Russell to do because it will mean that he can’t be lyrical and have people running through trees and fields of corn.”

She has become completely jaundiced by the live theatre, positively iconoclastic. “It is a dead loss, she says damningly. “Boring and tedious to work in. Everything about it is wrong these days – the theatres themselves, the plays they put on, the large companies. It would have to be a marvellous play to tempt me back.

From the archive, 8 April 1970: Women In Love and sex on the big screen

Read more

In the theatre what happens is that you find something in a rehearsal and spend another five weeks trying to re-create it each night which is really a remembrance of things past. It gets dreary after a bit and I’m certainly out of key with that way of acting. I love the immediacy of films – you find it then and there and once you’ve found it, it’s done and then you are on to the next.”

Her next, after Tchaikovsky, will be John Schlesinger’s Bloody Sunday – with an original screenplay by Penelope Gilliat. She will again be playing a fraught, neurotic woman. She feels that playing “an out-and-out lunatic” in The Marat/Sade has rather set the trend for these downbeat roles.

Certainly she never gets offered a comedy which is a great pity since site has a very sharp sense of humour. An example of this was where she went to an after-theatre party in New York given by Jackie Kennedy, one of her rare outings, wearing a £2 cotton frock from M and S, hair in rats’ tails, and a pair of sunglasses to keep her fringe out of her eyes. “I thought that was great fun,” she says, “with the rest of them dripping diamonds down to their navels.”

Reluctantly, she agrees that the parts in films she is now getting offered are “star” roles. Certainly she will be one of the first women film stars to break all of the rules.

How to access past articles from the Guardian and Observer archive

Less is more as Glenda Jackson exudes command in Deborah Warner’s fitfully brilliant production

Published on Sun 13 Nov 2016

Sandpaper voice; gliding movement; complete, ferocious concentration. Glenda Jackson cleavers her way through the part of King Lear. I was expecting her to be good. I was not prepared for her being one of the most powerful Lears I have seen.

It is not simply what Jackson does that makes her so authentic. It is what she does not do. No wavering voice, no rheumy eyes. Command shines out of her. In many productions when the disguised Kent says he sees authority in the old king’s face, it is hard to see what he means through the regal shambles. Not here. This monarch treats even her own emotions as if they were unruly lackeys. Scorn is a strong note. The curses are relished, delivered in a voice that sounds like a football rattle. The steps to madness are precisely marked. Nothing is wasted; nothing is superfluous. Which is one kind of great acting: it’s the economy, stupid.

Women in Love is Glenda Jackson’s first film to have an automatic release. By the time she finished it she was six months pregnant. Now she is playing the mad wife of Tchaikovsky, again in a Ken Russell film, and next year expects to play the Dorothy Tutin part in The Devils – again for Ken Russell. Being a rather severe artist herself, she says characteristically that “this will be a very good thing for Ken Russell to do because it will mean that he can’t be lyrical and have people running through trees and fields of corn.”

She has become completely jaundiced by the live theatre, positively iconoclastic. “It is a dead loss, she says damningly. “Boring and tedious to work in. Everything about it is wrong these days – the theatres themselves, the plays they put on, the large companies. It would have to be a marvellous play to tempt me back.

From the archive, 8 April 1970: Women In Love and sex on the big screen

Read more

In the theatre what happens is that you find something in a rehearsal and spend another five weeks trying to re-create it each night which is really a remembrance of things past. It gets dreary after a bit and I’m certainly out of key with that way of acting. I love the immediacy of films – you find it then and there and once you’ve found it, it’s done and then you are on to the next.”

Her next, after Tchaikovsky, will be John Schlesinger’s Bloody Sunday – with an original screenplay by Penelope Gilliat. She will again be playing a fraught, neurotic woman. She feels that playing “an out-and-out lunatic” in The Marat/Sade has rather set the trend for these downbeat roles.

Certainly she never gets offered a comedy which is a great pity since site has a very sharp sense of humour. An example of this was where she went to an after-theatre party in New York given by Jackie Kennedy, one of her rare outings, wearing a £2 cotton frock from M and S, hair in rats’ tails, and a pair of sunglasses to keep her fringe out of her eyes. “I thought that was great fun,” she says, “with the rest of them dripping diamonds down to their navels.”

Reluctantly, she agrees that the parts in films she is now getting offered are “star” roles. Certainly she will be one of the first women film stars to break all of the rules.

How to access past articles from the Guardian and Observer archive

King Lear review – Glenda Jackson is magnificent

Old Vic, London

Old Vic, London

Less is more as Glenda Jackson exudes command in Deborah Warner’s fitfully brilliant production

‘One of the most powerful Lears I have seen’: Glenda Jackson as King Lear, with Rhys Ifans, ‘genuinely funny’ as the Fool. Photograph: Tristram Kenton/The Observer

Susannah Clapp

@susannahclapp

Susannah Clapp

@susannahclapp

Published on Sun 13 Nov 2016

Sandpaper voice; gliding movement; complete, ferocious concentration. Glenda Jackson cleavers her way through the part of King Lear. I was expecting her to be good. I was not prepared for her being one of the most powerful Lears I have seen.

It is not simply what Jackson does that makes her so authentic. It is what she does not do. No wavering voice, no rheumy eyes. Command shines out of her. In many productions when the disguised Kent says he sees authority in the old king’s face, it is hard to see what he means through the regal shambles. Not here. This monarch treats even her own emotions as if they were unruly lackeys. Scorn is a strong note. The curses are relished, delivered in a voice that sounds like a football rattle. The steps to madness are precisely marked. Nothing is wasted; nothing is superfluous. Which is one kind of great acting: it’s the economy, stupid.

Rhys Ifans (Fool) and Glenda Jackson (King Lear) at the Old Vic. Photograph: Tristram Kenton/The Observer

Jackson makes the hoo-hah about Lear being played by a woman look like an old-fashioned load of fussing. That fuss has rather obscured the importance of another woman’s work. Deborah Warner has been a trailblazing director: it is 21 years since she brilliantly directed Fiona Shaw as Richard II. It used to be said that more men got more first-class degrees than women because they were less cautious. Less afraid of making mistakes, they apparently have more flashes of brilliance. Warner turns that idea on its head. More than any other director she produces wonderfully good and really duff moments. Sometimes within one production.

Glenda Jackson returns to the stage as King Lear – in pictures

Read more

As here. Throughout she uses the stage in an extraordinary way, continually bringing the action from its depths: it is as if the audience sees tragedy coming towards it through the mists of time. Yet she sets the play in what looks like a rehearsal room, with everyone in modern dress: all the women wear trousers. The design – on which Warner has collaborated with the French designer and artist Jean Kalman – is of featureless dun-coloured screens that you might find in a conference centre. The idea that we might be watching a run-through may appeal to Brechtians; not to me, for whom the power of Lear lies in its dreadful uncompromising finality. And in its untrammelled bellowing. Which Warner does capture in a tremendous storm scene: the stage is engulfed in billowing black plastic, shot through with zigzags of silvery light.

This is an uneven cast. Celia Imrie and Jane Horrocks, both actors I would travel to see, are strangely underpowered as Goneril and Regan. Karl Johnson’s Gloucester splutters monotonously, and his sons are disappointing. As Edmund, Simon Manyonda overexerts himself: through crucial speeches he moons, wanks, skips with a rope. Harry Melling’s Edgar throws away the beautiful clifftop speech: he clucks over the samphire gatherer’s “dreadful trade” as if he were offering careers advice. Yet as the Fool, Rhys Ifans brings a gentle warmth to the stage. He is also genuinely funny, particularly when embellishing with a saucy aside – “Hello Mike” – or a snatch of Dylan on his mouth organ. Lear can withstand this unevenness: its drama is so fragmented and ragged. And it is worth travelling through hurricano and cataract to see Jackson.

• At the Old Vic, London until 3 December

Jackson makes the hoo-hah about Lear being played by a woman look like an old-fashioned load of fussing. That fuss has rather obscured the importance of another woman’s work. Deborah Warner has been a trailblazing director: it is 21 years since she brilliantly directed Fiona Shaw as Richard II. It used to be said that more men got more first-class degrees than women because they were less cautious. Less afraid of making mistakes, they apparently have more flashes of brilliance. Warner turns that idea on its head. More than any other director she produces wonderfully good and really duff moments. Sometimes within one production.

Glenda Jackson returns to the stage as King Lear – in pictures

Read more

As here. Throughout she uses the stage in an extraordinary way, continually bringing the action from its depths: it is as if the audience sees tragedy coming towards it through the mists of time. Yet she sets the play in what looks like a rehearsal room, with everyone in modern dress: all the women wear trousers. The design – on which Warner has collaborated with the French designer and artist Jean Kalman – is of featureless dun-coloured screens that you might find in a conference centre. The idea that we might be watching a run-through may appeal to Brechtians; not to me, for whom the power of Lear lies in its dreadful uncompromising finality. And in its untrammelled bellowing. Which Warner does capture in a tremendous storm scene: the stage is engulfed in billowing black plastic, shot through with zigzags of silvery light.

This is an uneven cast. Celia Imrie and Jane Horrocks, both actors I would travel to see, are strangely underpowered as Goneril and Regan. Karl Johnson’s Gloucester splutters monotonously, and his sons are disappointing. As Edmund, Simon Manyonda overexerts himself: through crucial speeches he moons, wanks, skips with a rope. Harry Melling’s Edgar throws away the beautiful clifftop speech: he clucks over the samphire gatherer’s “dreadful trade” as if he were offering careers advice. Yet as the Fool, Rhys Ifans brings a gentle warmth to the stage. He is also genuinely funny, particularly when embellishing with a saucy aside – “Hello Mike” – or a snatch of Dylan on his mouth organ. Lear can withstand this unevenness: its drama is so fragmented and ragged. And it is worth travelling through hurricano and cataract to see Jackson.

• At the Old Vic, London until 3 December