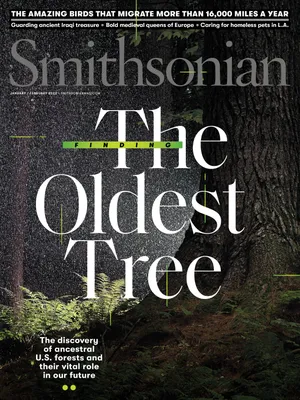

Ecologists thought America’s primeval forests were gone. Then Bob Leverett proved them wrong and discovered a powerful new tool against climate change

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/60/cd60e3bd-b058-454b-9f41-93dce7ee202a/20210613_smithsonianforest_0431.jpg)

LONG READ

By Jonny Diamond

Photographs by David Degner

I meet Bob Leverett in a small gravel parking lot at the end of a quiet residential road in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. We are at the Ice Glen trailhead, half a mile from a Mobil station, and Leverett, along with his wife, Monica Jakuc Leverett, is going to show me one of New England’s rare pockets of old-growth forest.

For most of the 20th century, it was a matter of settled wisdom that the ancient forests of New England had long ago fallen to the ax and saw. How, after all, could such old trees have survived the settlers’ endless need for fuel to burn, fields to farm and timber to build with? Indeed, ramping up at the end of the 17th century, the colonial frontier subsisted on its logging operations stretching from Maine to the Carolinas. But the loggers and settlers missed a few spots over 300 years, which is why we’re at Ice Glen on this hot, humid August day.

To enter a forest with Bob Leverett is to submit to a convivial narration of the natural world, defined as much by its tangents as its destinations—by its opportunities for noticing. At 80, Leverett remains nimble, powered by a seemingly endless enthusiasm for sharing his experience of the woods with newcomers like me. Born and raised in mountain towns in the Southern Appalachians, in a house straddling the state line between Georgia and Tennessee, Leverett served for 12 years as an Air Force engineer, with stints in the Dakotas, Taiwan and the Pentagon, but he hasn’t lost any of his amiable Appalachian twang. And though he’s lived the majority of his life in New England, where he worked as an engineering head of a management consulting firm and software developer until he retired in 2007, he comes across like something between an old Southern senator and an itinerant preacher, ready to filibuster or sermonize at a moment’s notice. Invariably, the topic of these sermons is the importance of old-growth forest, not only for its serene effect on the human soul or for its biodiversity, but for its vital role in mitigating climate change

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/80/78807fd3-b0de-4e62-a4c5-9d3bf46f57d3/janfeb2022_a11_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

As we make our way up the trail, the old-growth evangelist, as Leverett is often called, explains that though individual trees in New England have famously escaped the ax—the nearly 400-year-old Endicott pear tree in Danvers, Massachusetts, comes to mind—when ecologists discuss old growth, they’re talking not about single specimens but about systems, about uninterrupted ecological cycles over time. These are forests sustained by myriad sets of biological processes: complex, interconnected systems of perpetual renewal. While there is no universally accepted definition of old growth, the term came into use in the 1970s to describe multispecies forests that had been left alone for at least 150 years.

And that’s exactly what we’re seeing at Ice Glen, so-named for the deposits of ice that lived in its deep, rocky crevasses well into the summer months. Hemlocks hundreds of years old loom over gnarled and thick-trunked sugar maples as sunlight thickens into shadow through a cascade of microclimates. White pines reach skyward past doomed ash trees and bent-limbed black birch; striped maples diffuse a chlorophyll green across the forest floor through leaves the size of lily pads, while yellow birch coils its roots around lichen-covered rock; long-ago fallen, moss-heavy nurse logs return to earth only to re-emerge as philodendron and hemlock. Elsewhere, maidenhair, blue cohosh and sassafras abound, auguries of a nutrient-heavy, fertile forest floor. Walking through woods like these, the kind of hemlock-northern hardwood forests that once thrived in the Appalachians from Maine to North Carolina, is an encounter with deep time.

Beginning in the early 1980s, Leverett started to notice something on his weekend hikes in the New England forests: Every so often, in hard-to-reach spots—the steep sides of mountains, along the edges of deep gorges—he would encounter a hidden patch of forest that evoked the primeval woods of his childhood, the ancient hemlocks and towering white pines of the Great Smoky Mountains. But the idea that these New England sites were ancient remnant forest flew in the face of orthodox thinking.

This article is a selection from the January/February issue of Smithsonian magazine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/30/7c30e0d5-690c-4bcb-b490-ac84337dcad2/janfeb2022_a01_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

“A lot of people were skeptical: Even forest ecologists at universities had just given up on the idea that there was any old growth in Massachusetts,” says Lee Frelich, director of the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology and a longtime friend of Leverett’s. “They just didn’t know how to recognize certain types of old growth—nobody in New England could see it.”

The turning point in Leverett’s nascent evangelism was when he went public with his observations in the Spring 1988 edition of the magazine the Woodland Steward, with an article about discovering old-growth forest in Massachusetts’ Deerfield River Gorges. The reaction among forest ecologists was unexpected, at least to Leverett. “By Jove, my telephone started ringing off the hook. People I’d never imagined getting to know called and said, ‘Are you really finding old growth in the Berkshires?’”

One of those calls was from Tad Zebryk, a Harvard researcher who asked Leverett if he could tag along to look at some of these trees. Leverett invited Zebryk for a hike near the New York-Massachusetts border, not far from the town of Sheffield, Massachusetts. “I was pretty comfortable that it was old growth—it’s around a waterfall, rather inaccessible to what would have been original lumbering operations,” Leverett recalls. Zebryk brought along an increment borer, a specialized extraction tool for making field estimates on the age of a tree based on its rings, and the two tramped along the watershed. “I pointed to a tree and I said, ‘Tad...I think if you core that hemlock, you’re going to find that it’s pretty old.’ And I thought to myself, maybe 300, 330 years old.”

Leverett is good with a yarn, and he has told this story—his origin story—many times. “Well, [Tad] didn’t buy that at all but he took me up on my offer and, as God as my witness, he did a field count, and it came out to 330 years. My stock went through the roof.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/cf/3dcfcca5-f762-468b-b47b-f524c4d85e5a/janfeb2022_a09_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

When you have a lead on the biggest or the oldest tree, you call Leverett.

Ever the engineer, Leverett had also begun taking meticulous measurements of the height and circumference of old trees, and just a few years after the Woodland Steward article, he came to another startling realization: The height of American tree species, for generations, had been widely mismeasured by loggers and academics alike. This deep attention to detail—Bob’s remarkable capacity for noticing basic facts about the forest that others had overlooked—would fundamentally change our understanding of old forests, including their potential for mitigating the effects of climate change.

If the goal is to minimize global warming, climate scientists often stress the importance of afforestation, or planting new forests, and reforestation, or regrowing forests. But there is a third approach to managing existing forests: proforestation, a term coined by climate scientist William Moomaw to describe the preservation of older existing forests. (Moomaw was a lead author of five major reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.) All of these strategies have a role to play. But what Leverett has helped show in the last few years is how much more valuable proforestation is than we first thought. He has provided hard data that older trees accumulate far more carbon later in their life cycles than many had realized: In studying individual Eastern white pines over the age of 150, Bob was able to determine that they accumulate 75 percent of their total carbon after 50 years of age—a pretty important finding when every year counts in our struggle to mitigate the effects of climate change. Simply planting new forests won’t do it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/25/d8/25d84a68-5837-44ac-b0f0-b73d13b0a1b8/janfeb2022_a10_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

As Leverett recalls it, one of his biggest insights came on a summer day in 1990 or 1991. He was measuring a large sugar maple deep in Massachusetts’ Mohawk Trail State Forest, about five miles south of the Vermont border. Something was badly off with his measurements, which were telling him he’d just discovered the tallest sugar maple in history. Leverett had seen enough big sugar maples in his life to know that this was definitely not the case.

The next time he went to measure the tree, Leverett brought along a specialist in timber-frame construction named Jack Sobon, who had a surveyor’s transit level. Using the transit, they cross-triangulated their positions relative to the tree, the better to account for its lean. And this is when Leverett and Sobon realized something critical: Measuring for height, no one, apparently—not lumberjacks, not foresters, not ecologists—had been allowing for the plain fact that trees grow crooked. Back then, Leverett explains, the standard way to field-measure a tree was pretty simple, and had been used for decades: “You stretch a tape out, level with your eye, to the trunk of the tree, then take an angle to the top and an angle to the bottom. This is basically treating the tree like it’s a telephone pole in a parking lot, with the top vertically over the base—but 99 percent of trees aren’t so conveniently shaped.” Leverett would discover over the subsequent years that this same method had led to widespread mismeasurement of numerous tree species.

We are standing over the fallen remains of that very same sugar maple on a drizzly fall day some 30 years later. “That was the mistake I made [at first]—the top wasn’t over the base....I was off by about 30 feet.”

Over the years, and often in collaboration with ecologist Robert Van Pelt from the University of Washington, Leverett would develop and popularize a better, more accurate way to estimate the height a tree, which is known as the sine method and is accurate to within five inches. But Leverett’s innovations haven’t been just about height: He’s also developed precise ways to approximate trunk, limb and crown volume. The resulting larger estimates of how much space old trees occupy have contributed to his discoveries about their heightened carbon-capture abilities. A recent study Leverett co-authored with Moomaw and Susan Masino, a professor of applied science at Trinity College in Connecticut, found that individual Eastern white pines capture more carbon between 100 and 150 years of age than they do in their first 50 years. That study and others challenge the longstanding assumption that younger, faster-growing forests sequester more carbon than “mature” forests. The research bolsters the importance of proforestation as the simplest and most effective way to mitigate climate change through forests. Indeed, according to a 2017 study, if we simply left the world’s existing forests alone, by 2100 they’d have captured enough carbon to offset years’ worth of global fossil-fuel emissions—up to 120 billion metric tons.

Walking through woods like these is an encounter with deep time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/c9/3ec9f486-0f5b-4273-ba69-038363f11469/janfeb2022_a07_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

As Frelich says, “It turns out that really, really old trees can keep putting on a lot of carbon at much older ages than we thought possible. Bob was really instrumental in establishing that, particularly for species like white pine and hemlock and sugar maple in New England.”

Over the decades, Leverett’s work has made him a legend among “big-tree hunters,” those self-identified seekers who spend their weekends in search of the tallest, oldest trees east of the Mississippi. Big-tree hunters are more like British trainspotters than gun-toting outdoorsmen: They meticulously measure and record data—the height of a hemlock, the breadth of an elm—for inclusion in the open database maintained by the Native Tree Society, co-founded by Leverett. The goal, of course, is to find the biggest tree of a given species. As with any amateur pursuit, there is disagreement as to standards and protocols, but the one thing everybody seems to agree on is that when you have a lead on the biggest or the oldest, you call Leverett, who is always ready to talk big trees and will often travel to larger specimens to measure them himself.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/77/3377d538-000b-4a58-8fcc-d2828b59e53c/janfeb2022_a02_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

But Leverett’s ready acceptance by this community of tree-lovers, many of them amateurs, wasn’t necessarily reflected in the professional forestry community, which can feel like a tangle of competing interests, from forest managers to ecology PhDs. It was going to take more than a single visit to some 300-year-old hemlocks to convince them of old growth in the Northeast, so ingrained were assumptions of its disappearance. So Leverett set about to change that. In the early 1990s, he wrote a series of articles for the quarterly journal Wild Earth to help spread his ideas about old growth among the grassroots environmentalist community (it was Wild Earth co-founder John Davis who first dubbed Leverett the old-growth evangelist). In 1993, Leverett co-founded the Ancient Eastern Forest conference series, which brought forest professionals together with ecologists from some of the most prestigious academic departments in the country. His work at the conference series led to the publication of Eastern Old-Growth Forests: Prospect for Rediscovery and Recovery (an essay collection edited by Mary Byrd Davis, for which Leverett wrote the introduction), and he co-authored The Sierra Club Guide to the Ancient Forests of the Northeast with the late forest ecologist Bruce Kershner in 2004.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/87/bc872134-8713-42c7-82f5-8d5cdc0debc1/janfeb2022_a08_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

Since then, Leverett has led thousands of people on tours of old-growth forest under the aegis of groups like the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the Sierra Club and the Hitchcock Center for the Environment, and published scores of essays and articles, from philosophical meditations on the spiritual importance of old-growth forest, to more academic work. Leverett is also set to lead a workshop on tree measurement this May at Harvard Forest—the university’s forest ecology outpost in central Massachusetts—for scientists, forest managers and naturalists. Leverett literally wrote the book on how to measure a tree: American Forests Champion Trees Measuring Guidelines Handbook, co-authored with Don Bertolette, a veteran of the U.S. Forest Service.

Leverett’s evangelism has had a tangible impact on the preservation of old growth in his adopted home state of Massachusetts. As a prominent figure in a loose coalition of groups—the Massachusetts Forest Trust, the Native Tree Society, the Forest Stewards Guild, Friends of Mohawk Trail State Forest—dedicated to the identification and preservation of old-growth forest, Leverett’s work has prompted the commonwealth to add 1,200 acres of old growth to its forest reserves. At the heart of Leverett’s quest lies a simple message that continues to appeal to the scientist and spiritualist alike: We have a duty to protect old-growth forest, for both its beauty and its importance to the planet.

Back in Mohawk Trail State Forest, after paying our respects to the decaying remains of the mismeasured sugar maple, we tack gingerly downward through a boulder field, from fairytale old growth into a transitional forest—called an ecotone—of black cherry, big-tooth aspen, red maple and white ash. We find ourselves suddenly in a wide meadow under a low sky, as a light rain begins to fall. Moving through a waist-high varietal of prairie grass called big bluestem, we notice a couple approaching along a trail in bright puffy jackets. We hear their calls of greeting—there are very few people in the park today—and the woman asks if we are familiar with the area. “Intimately, I would say,” says Leverett, with typical good humor.

At the heart of Leverett’s quest lies a simple message.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/8e/7c8e8062-7d05-4590-aa41-cbb8260b5028/janfeb2022_a04_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

She asks if he knows where the Trees of Peace are—a grove of the tallest Eastern white pines in New England, so named, by Leverett, in honor of the Haudenosaunee belief that the white pine is a symbol of peace. Leverett named the individual pines for Native leaders whom he has come to know over the years, largely through his first wife, Jani A. Leverett, who was Cherokee-Choctaw, and who died in 2003. The tallest among them is the Jake Swamp pine, which, at 175 feet, is also the tallest tree in New England.

As it becomes apparent just how familiar Leverett is with the area, the woman’s eyes widen above her mask until, in a hushed tone, she asks, “Are you...are you Robert Leverett?”

Leverett says yes, and her eyes fill with tears.

Susan and her partner Kamal have been camping here the last few nights. The couple, from Boston, have already paid their respects to other parts of the woods but haven’t been able to find the Trees of Peace. Leverett leads us across the field and back into the forest.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fe/42/fe427947-9c6b-47e3-9866-036a3be7993e/janfeb2022_a06_oldgrowthtreehunters.jpg)

In all our conversations, Leverett is reticent about the extent of his influence. What he seems most interested in is how the forest affects individual people. “There’s a spiritual quality to being out here: You walk silently through these woods, and there’s a spirit that comes out. My first wife said, ‘You know, Bob, you’re supposed to bring people to the forest, you’re supposed to open the door for them. They’ll find out thereafter.’”

Leverett has led us to the center of the Trees of Peace. Susan and Kamal wander among the tall pines, each pausing to place a hand upon a trunk in quiet reverence. The storm that’s been threatening all day never really comes. Leverett leads us up and out, back along the main trail toward the park entrance. Email addresses and invitations are extended, and the couple express their gratitude. It feels like making plans in a church parking lot after a particularly moving Sunday service.

This is a familiar scene for Leverett: Over the decades, he has introduced thousands of people to old-growth forest. Ecologists and activists, builders and backpackers, painters and poets—no matter who he’s with, Leverett tells me, he wants to understand their perspective, wants to know what they’re seeing in the woods. It’s as if he’s accumulating a fuller, ever-expanding map of our collective relationship to the natural world.

“Other people are more eloquent in the way they describe the impact of the woodland on the human spirit,” he says. “I just feel it.”

Jonny Diamond | READ MORE

Writer Jonny Diamond, editor in chief of LitHub.com, is working on a history of the ax for W.W. Norton.

David Degner | READ MORE

David Degner is a photographer based in Cairo, Egypt.