How New York Times Fear-Mongering Helped Republicans Win the House

The paper told America that rising crime and worsening inflation were driven by Democrats. None of it was true.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2016 election, there was a lot of attention focused on the role of “fake news,” but a year later, a study published in the Columbia Journalism Review told a very different story, with the blunt title, “.” Instead of fake news — which was a real but relatively small problem in 2016 (all fake Russian ads amounted to 0.1 percent of Facebook’s daily advertising revenue) — it centered on an analysis of the New York Times‘ agenda-setting campaign coverage: America’s paper of record ran as many front-page stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails (10) in the last six days before the election as it did about all policy details combined in the two months before the election.

“If Clinton had a hard time getting her message out, she certainly didn’t get much help from the newspaper of record,” I wrote at the time. “Even though Trump got slightly more front-page scandal coverage than Clinton did, he faced nothing remotely like the six-day avalanche she endured.”

So I heard a sharp echo of the 2016 election on Nov 27, when the New York Times this way:

New York and its suburbs are among the safest large communities in the U.S. But amid a torrent of doomsday-style ads and headlines about rising crime, suburban swing voters helped drive a Republican rout that played a decisive role in capturing the House.

Once again, the Times was seeking to make sense of an unexpected election result — the GOP’s flipping of four suburban New York House districts — with zero apparent awareness of the crucial role its coverage had played.

Sure, Fox News played a role in driving national hysteria on crime, as shortly before the election. But in these particular districts, with majorities of Joe Biden 2020 voters, Fox could not have done it alone. The Times was implicated as well, and civil rights attorney Scott Hechinger, who heads , a criminal justice reform initiative, called it out in a . He called it “mindblowing” to see the Times, “one of the chief purveyors of false/misleading ‘doomsday headlines’ about crime in NY & around country — now reporting on the electoral impact of their own deeply harmful journalism practices. And yet mentioning only other papers & ‘media.'”

Hechinger reiterated these concerns to Salon by email: “I get far more concerned with outlets like NYT and NPR than Fox or NY Post because they are far more influential with the ‘gettable middle and moderates.'”

I wasn’t alone in hearing an echo of 2016, confirmed by Hechinger’s thread. One of the CJR study’s co-authors, Duncan Watts, confirmed the conclusion that the Times was willfully blind to the role it played. He wrote by email:

I continue to be amazed at the apparent inability or unwillingness of journalists (especially but not exclusively at the NYT) to acknowledge their own influence on the world. They write as if they are disinterested observers merely reporting on events over which they have had no influence, and over whose coverage they had no choice; yet neither of these assumptions seems remotely plausible to me.

Editors and journalists obviously have considerable discretion over what to cover (selection) — just look at the relative attention paid to Hillary Clinton’s email security and that of Jared and Ivanka not even a year later. I would argue, in fact, that almost any issue can be elevated to one of importance if the media chooses to focus on it, and almost any issue can relegated to insignificance if the media chooses to ignore it.

Hechinger was not alone in calling out the Times for misleading reporting about crime. Six months earlier, Alec Karakatsanis, founder and executive director of , made a after the California primary, specifically criticizing the Times’ story, “.” That article — based on two highly atypical, – campaigns, and — was typical of the Times‘ apparent impulse to shift the national narrative on crime rightward, regardless of .

It wasn’t just the Times‘ crime coverage that was deeply skewed to favor Republicans. Its obsessively inflation-focused coverage of the economy (again, certainly ) was similarly perverse, and also highly consequential.

“Why did we spend the past year or so reading daily stories about record high inflation but only occasional mention of record low unemployment?” Watts asked. “Both stories were true, but only one got consistent traction.” These two “Democrats in charge, situation out of control” narratives may have been custom-built in the Fox News ecosystem, but the Times eagerly gobbled them up and amplified them across the political spectrum, crowding out contrasting narratives in the process.

Kevin McCarthy’s county in Southern California had more than twice the 2021 murder rate of San Francisco, which Nancy Pelosi represents. Of course, neither of them was responsible for those startling statistics.

In the real world, murder rates rose in the wake of the pandemic, while broader measures of crime were more mixed, and neither had any intelligible relationship to congressional politics. According to , the murder rate in Kern County, home to likely incoming House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, was 13.7 per 100,000 in 2021, more than twice the rate of San Francisco, home to current Speaker Nancy Pelosi. But neither of those House members was responsible for those statistics. How could they be? Yet our political discourse was grounded in the fantasy that there was some relationship. The entire 2022 discussion about crime needs to be understood as a dangerous and damaging fantasy.

Nevertheless, Hechinger’s Twitter thread makes a compelling case for the Times culpability, highlighting key examples, such as how the paper’s unrelenting support for New York Mayor Eric Adams’ “tough on crime” approach and Republican gubernatorial candidate Lee Zeldin’s bad-faith attacks on Democrats, along with examples of a baseline “both sides” bias, if not a straightforward stenography of power

First, Hechinger commented on the , the day after a minor attempted assault on Zeldin during a campaign appearance on Long Island. The headline echoed campaign messaging — “G.O.P. Assails N.Y. Bail Laws After Suspect in Zeldin Attack Is Released” — and its first three paragraphs read like a GOP press release, concluding with a quote from the state party chairman:

“Only in Kathy Hochul’s New York could a maniac violently attack a candidate for Governor and then be released without bail,” Nick Langworthy, the New York Republican Party chairman, . “This is what happens when you destroy the criminal justice system.”

That accusation was patently false. As the , “New York’s bail law currently eliminates money bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies,” so the assailant’s release was dependent on a charging decision. And what wild-eyed fanatical reformer was that? As , “It took @nytimes *23 paragraphs* to expose the fact that the local DA — co-Chair of Zeldin’s campaign — could’ve sought bail. But declined to.”

Hechinger on a follow-up story that was headlined, ““:

The power & consequences of a headline. In the midst of a cynical assault on truth about bail reform by GOP extremist Lee Zeldin, NYT still only mustered a not-terrible, but disappointing “both-sides” story. But look at the headline. Few read beyond it. What message did it send?

Then there was the Times‘ fawning coverage of Adams, a Democrat (and former police captain) who’s generally been closer to Republicans on crime. Hechinger screen-capped a Maureen Dowd column, “,” :

The NYT lionized the hyper-carceral, chief crime propagandist. It began: “On a breezy June night in the Bronx, I was on the balcony at the restaurant Zona De Cuba, sipping a mojito, vibing to a salsa band & peeking at a special menu for the plant-based mayor of NY Eric Adams.”

He later linked to another story, “,” :

Look at this @nytimes headline. Made it seem like Mayor’s LIE was legitimate. It took 8 full paragraphs & 332 words before reporters stated the truth:

Bail reform had nothing to do with this. Also the teen was ultimately absolved & case dismissed.

Hechinger then linked to another story, “,” with the :

What was really strange about this headline from @nytimes is that the article actually *thoroughly debunked* the Mayor’s “plan” as lacking in any evidence, facts, or reason. No connection between reform & crime. No data to support policing plan. So… Why?

By email, Hechinger explained:

The NYT all too often at best presents a “both sides” picture when one of the sides is brazenly lying and the other is firmly backed by data and reason. And for a population conditioned by popular culture and sensational news media practices to thinking very simply and reactively about health and safety, they’re also going to be more comfortable believing the status quo.

A prime example cited in his thread was a screen-cap of the story headlined, “,” with this :

Doesn’t matter what nuance this @nytimes article might’ve brought. Most people don’t read beyond headlines. So most people thought “progressive prosecutors” led to a “surge” in “violent crime.”

Fact: Any increases & far more decreases occurred *everywhere.* 2 lies in 1 headline.

California’s Counter-Narrative

California, where we’ll turn our attention next, achieved its lowest crime rate in 50 years of recorded history in 2019 after years of criminal justice reforms, , head of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice:

- Statewide crime rates fell by 12 percent from 2010 through 2019, including a one-year decline of 3 percent from 2018 to 2019.…

- Crime declines accompany a period of transformational criminal justice reform, including the passage of Public Safety Realignment, Prop 47, Prop 57, and Prop 64. Despite initial concerns that these law changes would boost crime, most communities were safer in 2019 than at the start of the decade.

Ah, but how have things changed since 2019? Well, crime has risen in not-really-post-pandemic California, as in most of the country — but not evenly, as the Los Angeles Times reported in August, following release of statewide . In a column titled, “,” Anita Chabria wrote: “The biggest risks for homicides came in conservative counties with iron-fist sheriffs and district attorneys, places where progressives in power are nearly as common as monkeys riding unicorns.”

Kern County in inland Southern California — home to presumptive Speaker Kevin McCarthy, where Donald Trump got 54 percent of the vote in 2020 — was the most dangerous in the state, “with a homicide rate of nearly 14 people per 100,000, compared with about 6 per 100,000 for the state as a whole and 8.5 per 100,000 in Los Angeles County.”

Merced County, another inland county and “a political mixed bag,” was second-highest at 9.5 per 100,000 residents, and Tulare County (part of which McCarthy also represents, and where Trump also won) was No. 3 at 8.8 homicides per 100,000. “At the other end of the spectrum,” Chabria wrote, was Contra Costa County in the San Francisco Bay Area, “which has been successful at beating state averages on crime and has one of the state’s only (along with L.A.’s George Gascón) openly progressive district attorneys, Diana Becton.” The murder rate there “remains around 4 per 100,000 residents,” less than one-third of McCarthy’s home county.

A few months earlier, five days before the California primary, Males drew another comparison: “,” comparing the records of Sacramento DA Anne Marie Schubert, a candidate for state attorney general at the time, and San Francisco’s progressive prosecutors (Gascón, before moving to L.A., and the since-recalled Chesa Boudin) from 2014 to 2021. He reported that “Violent crime rates have risen an average of 9% in Sacramento while falling an average of 29% in San Francisco from 2014-2021,” the exact opposite of what the “tough on crime” crowd would have you believe.

But facts only partly mattered in the election that followed. Schubert got nowhere in the statewide race, but Boudin was recalled in San Francisco, buried in an avalanche of billionaire-fueled propaganda, as . As mentioned above, the Times ran a story on the Boudin recall which Pacifica Radio journalist Brian EdwardsTiekert picked apart in a focused on the actual details of how it happened, which concluded by suggesting: “Better headline: ‘Bucking regional trend, Bay Area’s fourth-largest county trades progressive DA for vague assurances of continued reforms under unknown successor.'”

The Times portrayed DA Chesa Boudin’s recall in San Francisco as illustrating a national trend. A better suggested headline: “Bay Area’s fourth-largest county trades progressive DA for vague assurances of continued reforms.”

In his Copaganda newsletter, Karakatsanis laid out a broader argument under the headline, “.” One aspect stood out, he wrote: There were “huge progressive criminal justice victories in California on election night, and the NYT just ignores them. I honestly could not believe what I was reading.” He linked to a , founder and CEO of Just Impact Advisors, highlighting a number of those victories, and added:

In fact, all over California and the country, continuing a multi-year trend, many progressive Democrats did very well (and a few didn’t) in elections about “criminal justice” issues. It’s astonishing that the New York Times doesn’t mention any of them.

So, what does NYT choose to focus on? 1) The recall of the DA in San Francisco in which Republican billionaire money flooded the race and created an overwhelming spending mismatch; and 2) The Los Angeles mayoral race, in which a former Republican billionaire spent $41 million on the primary. And although he outspent his nearest opponent by 10:1 ratio, he still only received 40% of the vote! 60% of the voters rejected his message.

It should be noted that the Los Angeles mayoral race predictably the Times narrative as Democratic mail-in votes came in, putting vastly-outspent progressive candidate Karen Bass seven points ahead. Bass went on to win the general election, despite another five months of right-wing-funded attack ads.

What’s more, Karakatsanis noted, the Times “neglected to tell readers that the ‘criminal justice reform’ policies of the San Francisco DA were actually enormously popular. Each of his major issues (not prosecuting kids, cash bail, wrongful convictions, worker protection, going after corrupt cops, and more) consistently polled with overwhelming support for nearly his entire tenure,” including the from mid-May, which showed 55% support for a workers’ rights protection unit, 65% support for an innocence commission and narrower pluralities in favor of not prosecuting children as adults and ending cash bail.

What drove the Boudin recall — beyond the vast sums spent to demonize him — was wildly inaccurate reporting across multiple issues, none more than the Times‘ own role in that an out-of-control shoplifting epidemic had led Walgreens to close five San Francisco stores, a story by the San Francisco Chronicle: “Data released by the San Francisco Police Department does not support the explanation announced by Walgreens that it is closing five stores because of .”

Karakatsanis wrote:

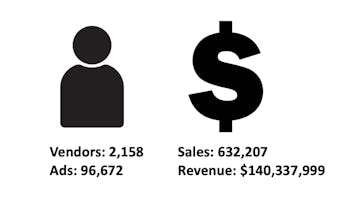

Using only these two local election-night results and ignoring all of the contrary evidence, NYT concocted a national story published at 5:00am the next morning about a reckoning for progressives and “shifting winds” on “criminal justice. According to Meltwater, this article had a potential “reach” of 170 million people after it was given prominent placement on the NYT website. The message to them? Democrats have to move right on crime.

As always with the New York Times, when you see articles like this, ask yourself: Why is this particular angle news? How did it get to the reporter and who pitched it? What is the goal of the article? How did they choose which voices to quote and which to ignore? Who benefits from framing the issue this way?

The sources cited, he argued, “overwhelmingly have political and business interests in promoting centrist, pro-police narratives,” even as the article “almost surgically excludes any other perspective, including the perspective of the many progressive strategists and candidates who have won on exactly the opposite message.”

That story was hardly unique; Karakatsanis takes a more extensive look at Times sourcing , concluding, “Instead of quoting or listening to other voices, the New York Times mocks them…. Because it doesn’t talk to anyone with different views, let alone explain them, NYT misleads the public with ludicrous strawperson arguments.”

Times sources cited in crime stories “overwhelmingly have political and business interests in promoting centrist, pro-police narratives,” Karakatsanis argues.

In the first installment of his Copaganda newsletter, “” Karakatsanis pointed out that he was “inspired by the gap in what mainstream media treats as urgent and what are the greatest threats to human safety, well-being, and survival,” noting as an example that air pollution kills 10 million people each year, but rarely makes the news. Instead the news is dominated by “crime” stories, but only about certain kinds of crime. He contrasts the recent with “retail shoplifting” from big corporate stores, to “the $137 million in corporate *every day,* including by the same companies whose press releases about shoplifting they now as victims.”

It’s worth noting that wage theft was Project Censored’s No. 2 story of the year, as for Random Lengths News, specifically focusing on reporting by the about how infrequently the offenders suffer any consequences. Drawing on 15 years of data from the Department of Labor, the report found that “The agency fined only about one in four repeat offenders during that period. And it ordered those companies to pay workers cash damages — penalty money in addition to back wages — in just 14 percent of those cases.” Talk about soft on crime! But that never hits the New York Times front page, and is never the subject of continuing political narratives, despite the fact that, at around , it dwarfs all other kinds of property crimes.

Well, almost all of them. Another massive crime wave that’s not news is tax evasion by the wealthy, which “could approach and possibly exceed $1 trillion per year,” according to Senate testimony earlier this year. This has been enabled by , thanks to Republicans. Which is why IRS agents are being hired with funding in the Inflation Reduction Act, leading Republicans to over Democrats getting too tough on crime.

Inflating Inflation

Republicans’ soft-on-crime approach — at least when the wealthy and powerful are involved — leads us to the next aspect of how the Times helped them flip the House: Misleading coverage of the economy and inflation. Recall that Watts asked, “Why did we spend the past year or so reading daily stories about record high inflation but only occasional mention of record low unemployment?” noting, “Both stories were true, but only one got consistent traction.”

A Proquest search of Times headlines for the entire year through Election Day bears this out. There were 709 hits for “inflation” and 141 for “recession,” but just 14 for “unemployment,” and 77 for “recovery” — of which only 13 were stories about economic recovery in the U.S.

I turned to Dean Baker, co-founder of the , whose “” blog began in the 1990s as commentary on faulty economic coverage in the Washington Post and the New York Times. Myopia, oversimplification and lack of historical perspective are the persistent problems he has pointed out, which he says continue to this day. He wrote by email:

I would say that the WaPo and NYT, along with most of the rest of the media, decided that the story of the economy was that inflation was hurting people, especially lower income people. They pushed this line endlessly, ignoring large amounts of evidence to the contrary. For example, wage growth was most rapid at the lower end of the wage distribution and of the workforce.

Other perspectives on the current economic picture were also missing, he continued.

The freedom to quit a job you don’t like, knowing that you can likely get a better one, has to be a really big deal for workers who often feel stuck in jobs that pay poorly or where the boss is a jerk. … In some pieces they practically lied. For example, the NYT had a piece just before the election saying that young people were unable to buy homes. In fact, the homeownership rate for young people had risen substantially since before the pandemic, and that was true for Blacks and Hispanics as well, also for lower income households.

Other facts were almost never mentioned, such as the “20 million people who refinanced their homes in the years 2020-22, saving themselves thousands in interest costs each year,” along with “an increase of roughly 10 million people working from home” who both had more personal time with no commute and “saved thousand of dollars a year in commuting costs and other expenses associated with going to an office.”

“In short,” Baker concluded, “the media decided that we had a terrible economy, and they were not going to let the data get in the way.”

Dean Baker offers a straightforward conclusion: “In short, the media decided that we had a terrible economy, and they were not going to let the data get in the way.”

In fact, inflation has been a worldwide problem, with the , so, as with crime, the dominant narrative has no grounding in plausible causal relationships. Did Democratic spending have an inflationary impact? Maybe the stimulus checks did — but they didn’t cause Germany to have higher inflation than the U.S. As for the Child Tax Credit, which , its effect was minimal, according to by macroeconomist Claudia Sahm. “Unlike stimulus checks that came out in a burst, accounting for 16% of disposable personal income in March 2021, the new Child Tax Credit was monthly to families and was 0.5% of income from July through December,” she writes.

American child poverty is way out of line with the rest of developed world, and has been for generations. Changing that would vastly improve the life outcomes of tens of millions of children — an enormous long-term benefit not just for those individuals and their families, but for our nation as a whole. To abandon that over an illogical fear of short-term inflation is foolish at best, criminally malicious at worst. But American politics didn’t allow any serious discussion about that, with Joe Manchin’s anecdotal fears derailing the entire issue.

The New York Times — here we go again — did nothing to counter that. Its role in helping Republicans win control of the House needs to be viewed through the lens of child poverty. By deciding which stories matter and which don’t, the Times decides which people matter and which don’t.

Of course the Times should not favor the Democrats, or privilege liberal or progressive arguments above others by default. But it should favor the truth on criminal justice and the economy, as on all other issues. In the election just concluded, greater doses of truth might well have benefited Democrats. But in the larger picture, if the media privileges factual arguments and evidence, that sets a bar both parties have an equal opportunity to meet. That kind of political competition is the hallmark of a healthy democracy.

Hechinger last year about the profound disconnect between known truths and journalistic practice:

Today, we know, both from experience and , that releasing people from jail prior to trial reduces crime for years in the future — and saves tens of millions of dollars in each major city. We also know, again based on experience and also the most robust criminogenic analysis in history — of 116 studies just released this month — that long sentences have zero effect on crime.

Yet journalism today continues to ignore these “” while instead following the familiar and dangerous patterns from the 1980s and ’90s that helped drive mass criminalization itself: overly simplistic stories with alarmist headlines and dehumanizing language that rely predominantly on police as sources, neglect nuance, provoke fear in the public, speculate about short term crime data — and posit police, prosecution, and prison as the solutions to crime.

Yet he remains doggedly determined and borderline optimistic, as he told me by email. The best thing “advocates for truth can do” is continue to criticize and engage, he wrote. Some mainstream journalists “have been open to conversations and have listened constructively”:

My concern is that the same patterns I wrote about in the Nation and keep plugging away at on Twitter keep persisting, & with some reporters getting worse. As someone who follows the truth and data closely, works with amazing folks around the country who are successfully achieving public health and safety without relying on mass police and jailing, and who represented thousands of people directly targeted, harmed and marginalized by the very policies the New York Times intentionally or otherwise reinforces, I care deeply about the Times getting it right.

PAUL ROSENBERG is a California-based writer/activist, senior editor for Random Lengths News, and a columnist for Al Jazeera English.