Arshad R. Zargar

Thu, June 22, 2023

New Delhi — Glaciers in the Hindu Kush region of the Himalaya mountains are melting at the fastest rate ever and could shed as much as 80% of their ice by the end of this century if global warming continues unchecked, a group of international scientists warned in an alarming new report.

The study says the melting of the glaciers will directly impact billions of people in Asia — causing floods, landslides, avalanches and food shortages as farmland is inundated. Indirectly, the melting of such a vast reserve of fresh water could impact countries as far away as the United States, even the whole of humanity, according to the report by the Nepal-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

The academic paper warns the ice and snow reserves in the Hindu Kush Himalayas (HKH) region are melting at an "unprecedented" rate and that the environmental changes to the sensitive region are "largely irreversible."

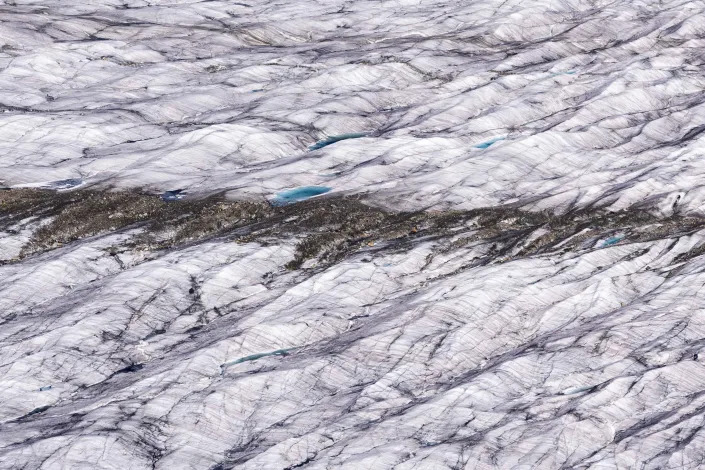

Glaciers are seen in the Pamir Mountains, a range in Central Asia formed by the junction of the Himalayas, Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun and Hindu Kush mountain ranges, as seen in a file photo taken from the Karakoram Highway, in Xinjiang, China. / Credit: The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range in Central Asia formed by the junction of the Himalayas, Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun and Hindu Kush mountain ranges. They are among the world's highest mountains and since Victorian times they have been known as

The HKH region spans roughly 2,175 miles, from Afghanistan to Myanmar, and is home to the highest mountains in the world, including Mount Everest. It contains the largest volume of ice on Earth outside the two polar regions and is the source of water for 12 rivers that flow through 16 Asian nations.

Those rivers provide fresh water to some 240 million people living in the HKH region, and about 1.65 billion people further downstream, the report says.

For all of those people, the melting of the glaciers would be a disaster. The report says they will face extreme weather events and crop loss that will force mass-migration.

Deadly floods and avalanches in the Himalayan region have already increased over the past decade or so, and scientists have linked the greater frequency and intensity of the disasters to climate change and global warming.

The ICIMOD report lays out three potential scenarios for the glaciers of the HKH: If there is a 1.5-2 degree Celsius increase in the Earth's average temperature above pre-industrial levels, the glaciers will lose 30% to 50% of their ice volume by 2100. If the global temperature rises by 3 degrees Celsius, the glaciers could lose 75% of their ice and, with a 4-degree rise, the researchers say there will be a loss of up to 80% of the ice in the HKH.

"These projections are of very high confidence as we say in the scientific language," Dr. Philippus Wester, the ICIMOD's Chief Scientist on Water Resources Management and the lead editor of the report, told CBS News. "In layman's language, it means we have no doubt whatsoever that at 2 degrees Celsius global warming, we will lose 50% of the glacial ice mass in the region."

The report notes that the Himalayan glaciers lost ice at a rate 65% faster between 2010 and 2019 than over the previous decade (2001-2010).

"This is a lot, this is alarming," Wester told CBS News."On human time scales, we have never seen glacial melt this rapid, this fast… this is unprecedented."

Other research shows Mount Everest's glaciers have lost the equivalent of 2,000 years' worth of ice over just the past three decades. In a 2019 report, the ICIMOD said the Himalayan glaciers of the region would lose at least one third of their ice if the average global temperature was limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius. But with new technology and more data becoming available over the last five years, the scientists found circumstances worse than they expected, Wester said.

Global impact of the melting Himalayan glaciers

The impacts of the rapid glacial melt in the Himalayas will be felt around the world, Izabella Koziell, deputy director general of the ICIMOD, CBS News this week [video available at the top of this article].

"Even if this feels remote to us sitting far away, it is going to affect us — whether that is through mass people movement or sea-level rise. When the glaciers in the Himalayas melt, the ice sheets in Greenland, Arctic and Antarctic are also melting. This means there will be sea level rise, there will be quite dramatic changes in ocean circulation as a result of increase in fresh water into oceans, and this will have huge impacts on us," Koziell said.

"The people who are losing their livelihoods, of which there are 2 billion people — that's a quarter of the world's population — where will they go? They will have to go and find safer places and we will have to offer those safer places for them to live," Koziell said.

Earlier this month, scientists warned at the Bonn Climate Change Conference of the worrying speed and scale of ice-melt worldwide. Another study, published last year, said the Arctic could start to see periods during the summer without any ice remaining at all by 2030, even if emissions are cut drastically.

"Clarion call" for urgent climate action

Scientists are calling for urgent action to slow global warming to preserve as much of the ice mass in the Himalayas as possible.

"To prevent additional ice loss, greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced through the use of clean and renewable energy sources… cooperation among Himalayan nations and international organizations is required," Professor Anjal Prakash, an author on the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), told CBS News.

"We need to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as we can. The less melt we have, the better it is because it takes such a long time to recover from that loss," the ICIMOD's lead editor Wester told CBS News.

The U.N.'s IPCC says limiting warming to around 1.5 degrees Celsius requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025, and be reduced by 43% by 2030. The world is not currently on course to keep those targets within reach.

"This is a clarion call," Wester told CBS News. "The world is not doing enough because we are still seeing an increase in the emissions year-on-year. We are not even at the point of a turnaround in terms of emissions."

"The change we are causing now will not stop even if we keep emissions at current levels," Koziell told CBS News, but she added that "all hope is not lost."

"If we commit to decarbonisation now, we still have an open window. We seriously need to keep that window open," Koziell said. "We need to seriously commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and whatever investments we make now, will be a benefit for the future."