Tom Fordy

Tue, 24 October 2023

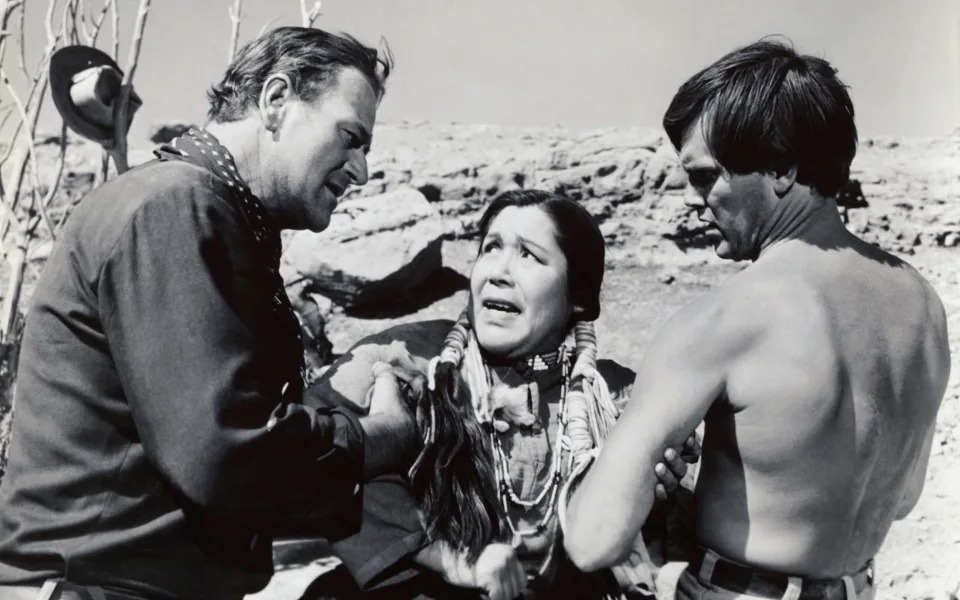

Marilyn Monroe with extras on the set of her 1954 film River Of No Return - Moviepix

Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon may have racked up five-star reviews across the board, but not everyone has been enthusiastic.

The film tells the story of the Osage Indian murders in 1920s Oklahoma. Leonardo DiCaprio plays Ernest Burkhart, who – along with his uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro) – conspires to poison Burkhart’s Native American wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), in a plot to seize Osage oil land headrights.

Christopher Cote, an Osage language consultant for Scorsese, attended the premiere and told The Hollywood Reporter he had “some strong opinions” about the finished film. “As an Osage, I really wanted this to be from the perspective of Mollie and what her family experienced,” said Cote, “but I think it would take an Osage to do that.”

The criticism comes despite efforts from Scorsese to not make this story about white people. Scorsese had dinners and meetings with members of the Osage Nation and – based on these meetings – decided to change the perspective of the script, to steer it away from a white saviour narrative about law enforcement investigating the case.

Scorsese worked with Osage Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear, and local Osage people were also employed in behind-the-scenes and consultant roles. “But no Native American is credited as being involved in the movie’s screenwriting, production or directing creative processes,” wrote Angela Aleiss, a film historian and author of several books on Native Americans in films. “This is an ongoing problem.”

Native Americans and Hollywood have a long history together. Depictions of Indians go back to some of the very first moving pictures. Angela Aleiss explains that film representations of Native people have gone through cycles – from noble savage to savage warrior, from hostile to sympathetic portrayals. More positive portrayals – as well as significant contributions from Native American filmmakers and actors – have been lost to time, since overshadowed by the more popular, negative stereotype: untamed Indians in headdresses, firing arrows at cowboys and talking in what Indigenous Canadian critic Jesse Wente called “Tonto speak”.

Over the years, Native American actors have had to go along with it. Navajo actor and filmmaker Brian Young wrote about the issue for Time Magazine. He vowed to never wear war paint and feathers again. “At some point, every Native American actor comes to a career crossroads and has to answer the question: do I participate in stereotyping or maintain my cultural integrity?” That’s if Native American actors are cast at all. Hollywood has a history of casting white actors as Indians – playing “red face”. Higher status “Indian chief” roles have gone to non-Native actors, while Native actors make up the background (not to mention lower paid) roles.

As recently as 2013 there was controversy over Johnny Depp playing Tonto in the Disney reboot of The Lone Ranger – then Rooney Mara playing Tiger Lily in 2015’s Pan. The problem, perhaps, is that movies – including Killers of the Flower Moon – are made through white eyes. Hanay Geiogamah – a Native American playwright, producer, and UCLA professor – agrees. “It’s not that complicated,” he says. “The only way to tell the American Indian’s story is for American Indians to write it.”

Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer in The Lone Ranger - Peter Mountain

Westerns – and Native Americans – became popular in the early days of silent cinema. By the time of the silent Westerns, Native people had been herded into reservations. “This part of American history, of course, was really still ongoing at the time cinema was really being born,” said Jesse Wente in the 2009 documentary, Reel Injun.

As noted by Angela Aleiss, early film studios pumped out one or two-reel pictures at a rate of around 12 to 15 per month (a reel amounted to around 10 minutes). Portrayals of Native people – sometimes sympathetic and romantic – were inspired by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West vaudeville show, dime novels, and classic literature, such as James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans. “The silent films were a mixed bag,” says Aleiss. “You had the savage warrior, the noble Indian, the ‘half-breed’. Then you had movies that very much said Indians were loyal.”

Director DW Griffith – best known for the landmark, KKK-glorifying epic, The Birth of a Nation – made 30 Indian-themed films. Thomas H. Ince – a pioneering producer dubbed “the father of the Western” – moved families of Oglala Sioux to his mountainside production village in Santa Monica.

Hollywood’s first Native American filmmaker was James Young Deer, who managed the West Coast base of Pathé Frères. He oversaw production of over 150 silent one-reel Westerns and enjoyed significant creative freedom. His films were quirky satires that subverted the already-traditional Western stories. Young Deer was also embroiled in Hollywood’s first sex scandal. In 1913, he was accused of introducing an actress into a sex-trafficking ring and then the rape of a 15-year-old. He fled to England but returned to the US, by which time his accusers were long gone. His career never fully recovered, though he did make the first film about the Osage murders – Tragedies of the Osage Hills. The film premiered in May 1926, just four months after the arrests of the men portrayed by De Niro and DiCaprio in Killers of the Flower Moon.

By the early 1930s, Westerns fell out of favour and were reduced to B-movie status – formulaic, churned-out films that often starred John Wayne. The Hollywood Indian became a stereotyped savage – all war bonnets, teepees, and Tonto speak. These films would later fill up TV schedules, cementing negative stereotypes. “In the 1960s, those B-movies were sold to TV,” says Aleiss. “People saw this very superficial thing of cowboys and Indians. There’s so much more out there that wasn’t sold to TV.” Indeed, there were films about the Native American experience – such as The Silent Enemy and Laughing Boy – but they flopped. “The problem is, people didn’t want to see it,” says Aleiss. “They didn’t line up.”

In 1936, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Plainsman reinvigorated the Western, followed by the John Ford-directed Stagecoach. In that film, John Wayne and a rabble of white folk journey to New Mexico – under the threat of attack from Geronimo and his bloodthirsty Apache warriors. “Stagecoach is the iconic Western,” said Jesse Wente in Reel Injun. “It’s the Western that all others were really modelled after and it’s one of the most damaging movies of Native people in history. You have white society inside the stagecoach and they are besieged – and on all sides – by Native people. By the wild of America.”

Even now, the stereotypes of those Westerns hold firm. Hanay Geiogamah describes being “instantly exotified” as a Native American. “There’s almost no way you can respond to it,” he says. One age-old stereotype seen in movies is the “drunken Indian”. “Even somebody like myself would be suspected of being a drunken Indian behind the scenes,” says Geiogamah. “Or I have a herd of horses in my backyard that I jump on, or I have a big tepee and prefer to sit in that than my house. All of that is so firmly rooted in the non-Indian mind. I don’t think non-Indian people employ this thinking in a mean, negative way. I think it’s just there.”

During the Second World War, onscreen relations between white Americans and Native people softened. “Studios didn’t want to send movies abroad where white people are shooting down Indians,” says Aleiss. “We were supposed to be fighting fascists and genocide.” Aleiss points to 1941’s They Died with Their Boots On, a history-bending biopic of Lieutenant Colonel George Custer (Errol Flynn), leading to his death at the Battle of Little Bighorn. “What happens to Custer is they modify him,” says Aleiss. “He becomes a friend and ally to Crazy Horse [the infamous Lakota who fought against Custer’s cavalry at Little Bighorn]. Custer even calls Crazy Horse his brother.”

In the film, Crazy Horse is played by Anthony Quinn, an American actor of Mexican-Irish descent. Many non-Indian actors took Native roles – standard practice in Hollywood. The likes of Burt Lancaster, Elvis, Rock Hudson, Burt Reynolds, Boris Karloff, Chuck Connors, Audrey Hepburn, Debra Paget, and Charles Bronson all played Native Americans. “The reason they give Indians is because, ‘Y’all don’t know how to act,’” says Geiogamah. “That’s just absolutely not true. There are some really good Indian actors. I know, I’ve worked with them in the theatre! But there’s still that perception built into the system.”

The issue of authenticity goes back to the early days of cinema. As noted in Aleiss’s 2005 book, Making the White Man’s Indian, trade magazine Moving Picture World praised a film in 1910 for using real Native actors. “The public is no longer satisfied with white men who attempt to represent Indian life,” wrote the magazine. “The actors must be real Indians.” The following year, a delegation of Chippewa people protested against “a false representation of Indian life” in a film called The Curse of the Red Man.

In 1936, the actor, author, and activist Luther Standing Bear started the Indian Actors Association in response to non-Native actors being cast in Indian roles. Members slated Indian stereotypes who “talk and grunt like morons” and demanded equal pay. Non-Indian extras were paid almost double what the actual Indian actors were paid. And roles were few and far between (which Brian Young was still saying in 2015).

Native American athlete Jim Thorpe – the first Native American to win an Olympic gold medal for the US, in fact – became a film bit-player and spoke out against casting non-Indian actors. “There are only a few pictures each year that we can work in and when they use white men it just means we can’t make a living,” he said. The decidedly white Burt Lancaster would play Thorpe in a 1951 film of his life, Jim Thorpe – All American.

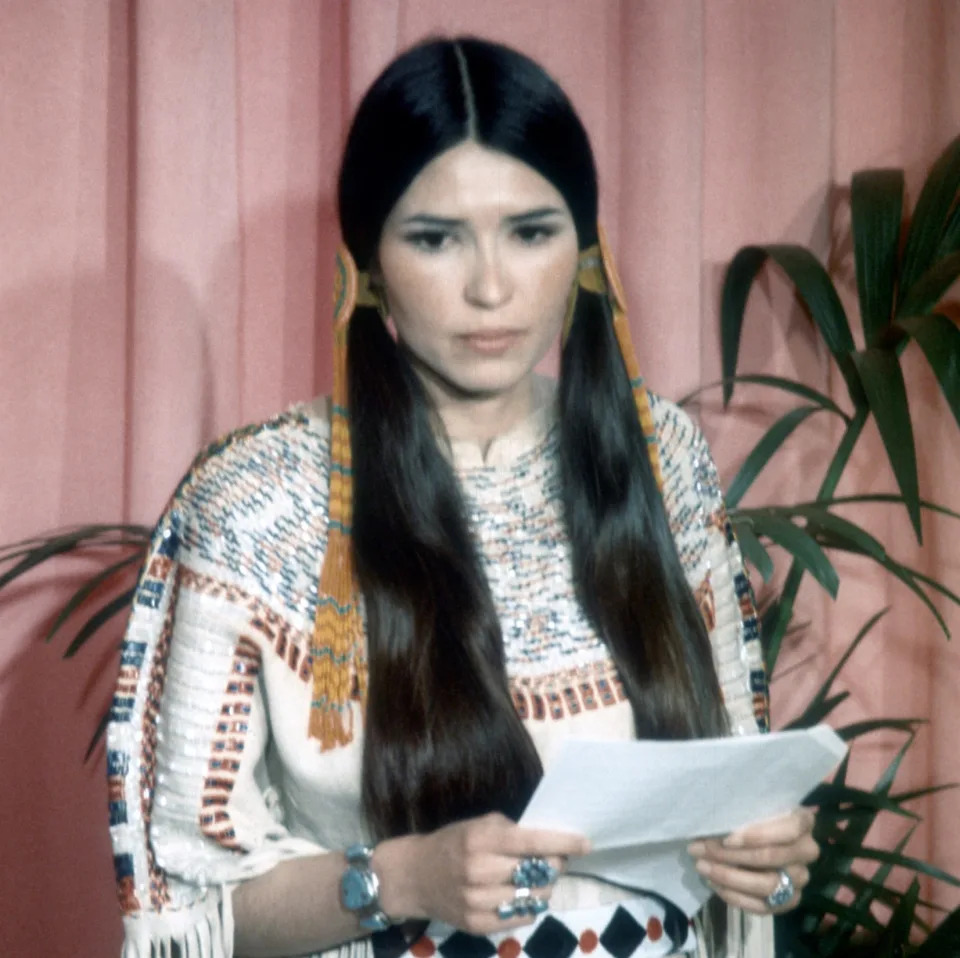

There were other issues of authentic Indian-ness: Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance claimed Canadian Blackfoot ancestry. It was revealed he was of mixed African-American descent. He later shot himself. Iron Eyes Cody was famous for playing Native American roles – most famously as the crying Indian in the anti-pollution commercial. Cody claimed Native heritage, though he was actually of Sicilian descent. Even Sacheen Littlefeather – who declined Marlon Brando’s Oscar at 1973 Academy Awards – was revealed to be of Mexican descent following her death last year. (Which the Native community apparently knew for years.)

Brando had boycotted the event to protest Hollywood’s treatment of Native Americans. Certainly, it was a bloody period for Native people on film. As detailed in Reel Injun, the American Indian became an allegorical tool amid anxieties over the Vietnam War. In 1970, Ralph Nelson’s Soldier Blue depicted the US cavalry carrying out a censor-troubling slaughter of a Cheyenne village – a nod to both the Sand Creek Massacre from 1864, in which US troops killed 230 people, and the My Lai Massacre, which happened in Vietnam barely two years before Soldier Blue.

There was more brutality in A Man Called Horse, also released in 1970, in which Richard Harris survives the savagery of the Sioux. The film provoked protests for its depiction of Sioux and for making a white man the hero. The director, Elliot Silverstein, clashed with the studio bosses over scenes of the Sioux laughing. The studio apparently thought that their Indians were too inhuman to laugh.

The Brando-Littlefeather protest came at the time of more real-world activism. From 1968 to 1971, Native American protestors and supporters staged a 19-month occupation of Alcatraz. In 1972, 500 Native Americans marched on Washington DC over political sovereignty. And in 1973, the American Indian Movement occupied Wounded Knee – the site of an 1890 massacre – in a two-month standoff with the FBI.

As the Hollywood legend goes, John Wayne was incensed at the Sacheen Littlefeather Oscars protest and had to be restrained. The story has been debunked in the years since. But Wayne’s Westerns created the kind of cultural damage that Brando was protesting against. The Searchers, released in 1956, contains awful stereotypes and has one of the most obscene assaults on Native Americans: Wayne’s hero – a bigoted cowboy – shoots out the eyes of an already-dead Comanche.

By the mid-1970s, Will Sampson – from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – became a new type of Indian hero. “He was trying to take the Indians out of the old cliches and put them into modern settings,” says Aleiss. “He was very successful at that.”

After falling out of favour, the Western – and Hollywood Indian – was revived by the huge success of Dances with Wolves in 1990, which was credited for humanising its Indians. The film also earned an Oscar nomination for Native Canadian actor Graham Greene. Dances with Wolves, however, has since been criticised for telling the story from a white perspective.

Hanay Geiogamah found the same problem when working on a series of five TV movies in the mid-1990s. “I worked with five white writers – five,” he says. “They were talented but they had no idea about Indian life. Not at all. I offered thematic suggestions that would have been really effective – it just didn’t happen. They were following the standard. They grew up on decade-after-decade of the Hollywood Indian persona. It was burned in their minds, like the minds of millions of American citizens.”

For Geiogamah, the portrayal of Native Americans is like so much else in the US: a matter of economics. “The Hollywood system has so many things built into it,” he says. “There has to be a star – a big white hero – a Robert Redford or John Wayne. The distortion begins immediately with the economic factors that are attached to the process.” That’s likely the reason Hollywood doesn’t have white actors playing red face now: because The Lone Ranger was a dud.

Geiogamah credits Little Big Man – the 1970 Western starring Dustin Hoffman – as a rare success in depicting Native Americans. Also, Chris Eyre’s 1998 comedy Smoke Signals, a then-rare story about modern day Native Americans – actually starring, written, and directed by Native talent, no less. Other recent, contemporary stories include the TV series Reservation Dogs and Rutherford Falls.

While many Hollywood portrayals have been sympathetic to Native Americans, that is perhaps not the same as culturally sensitive – particularly in the context of our current awareness of representation and cultural appropriation. Which is easy for a white man in 2023 to say. The history of protest within the industry shows that depictions that it’s long been an issue for Native Americans actors and filmmakers. As recently as 2015, there were reports of Native actors walking off the set of the Adam Sandler spoof, The Ridiculous 6, for offensive portrayals. The reports were apparently overblown but the story tapped into still-present tensions. For Geiogamah, Hollywood’s attempts at telling Native stories is “by and large a failure”.

Angela Aleiss is keen to stress the achievements of Native actors and filmmakers. That’s the subject of Aleiss’s book, Hollywood’s Native Americans. Aleiss points back to Chickasaw filmmaker Edwin Carewe, who made around 60 movies; Will Rogers, a Cherokee actor and mega-star of his day; and Jay Silverheels – TV’s Tonto – who started the Indian Actors Workshop. “Native people don’t have the numbers of black Americans, Asians, or Latinos in American society,” says Aleiss. “I think that’s why it’s important to look back and give them the credit they deserve.”

.jpg)