Private equity firms have been slow to cash out of holdings and hand money back to their investors. Executives at Investment Management Corp. of Ontario say they’re ready if that trend continues.

“Most of our partners will probably say that the worst is over. We are just patient,” said Rossitsa Stoyanova, chief investment officer of the $77.4 billion (US$57 billion) Canadian pension manager. “We are prepared that we are not going to have exits for a while.”

Private equity firms have seen a dramatic change in the investment climate since interest rates began their rapid climb in 2022. The high cost of borrowing has made it harder for them to finance new acquisitions, or find buyers for the assets they already hold at valuations they’ll find attractive.

Still, there have been signs of a thaw in deal activity so far in 2024 now that it appears the Federal Reserve and other central banks are poised to start lowering interest rates.

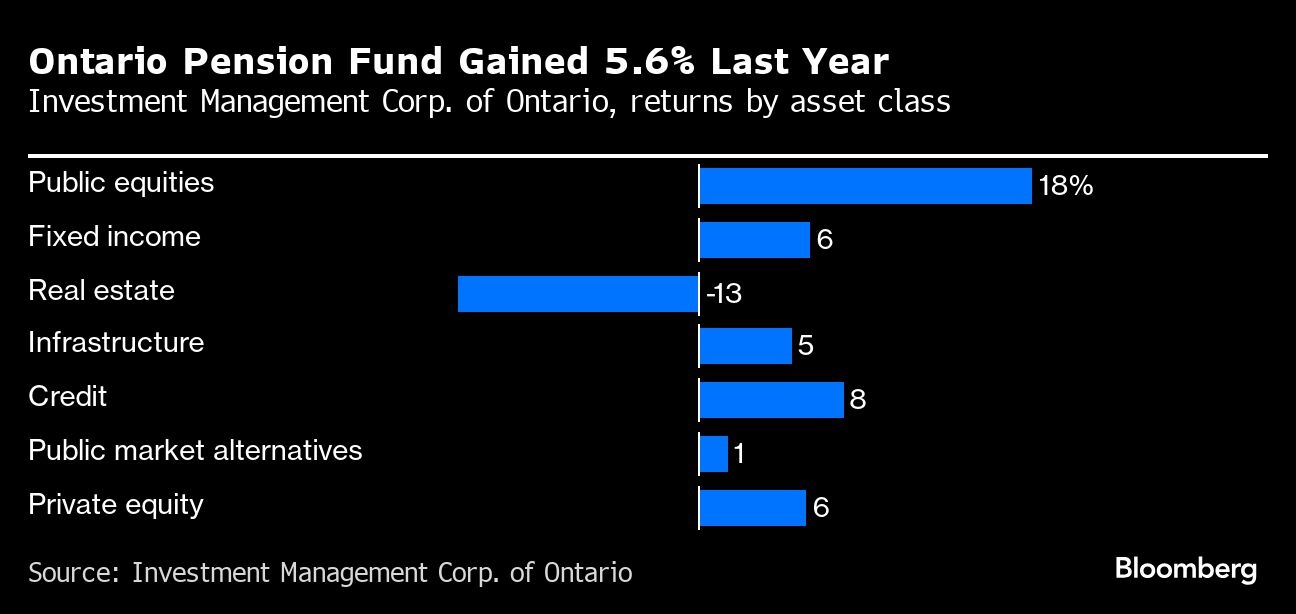

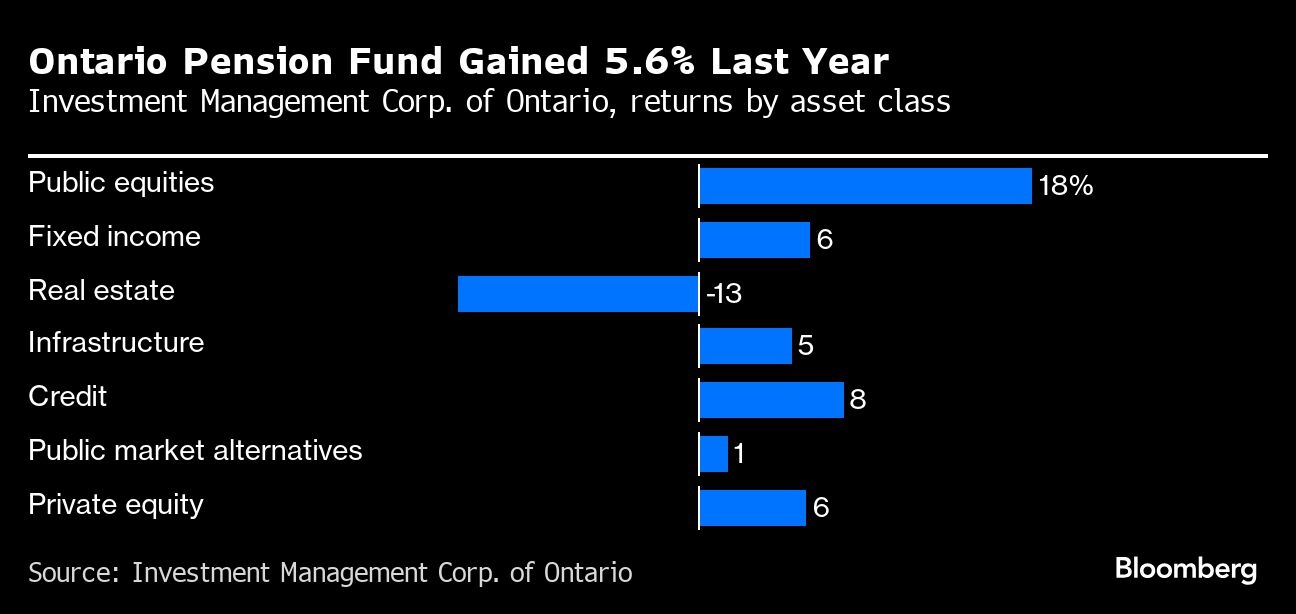

Overall, IMCO posted a 5.6 per cent return last year, underperforming the benchmark of 6.6 per cent, according to a statement Friday. The fund had positive returns in every major asset class except real estate, where it lost 13 per cent. It outperformed the benchmark in public stocks and fixed income, but undershot on private equity.

“It’s not that we saw something happening in 2023, or we were contrarians, Chief Executive Officer Bert Clark said in an interview. “We held to our long-term strategies and it worked.”

IMCO is a relative young organization, launched less than a decade ago to consolidate the management of a number of retirement funds for government workers in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. As such, it’s still building up some of its investing programs, including private equity and private credit.

Last year, the Toronto-based manager allocated $509 million to three new private equity partners, including European buyout funds managed by Cinven Capital and IK Investment Partners, and did nearly $1 billion in direct and co-investment PE deals.

The fund has also been growing its credit business, investing in everything from investment grade credit to structured private credit through external fund managers and co-investments — including allocations to funds run by Ares Management, Carlyle Group and Blackstone.

IMCO boosted its activity in private credit last year, raising it to nearly 50 per cent of the global credit portfolio as of December. Management plans to increase that to 70 per cent, according to the fund’s annual report.

IMCO is also look for exposure exposure to the infrastructure that supports the energy transition and artificial intelligence, according to Stoyanova. Last year, the fund committed $400 million in Northvolt AB, a Swedish sustainable battery company, via convertible notes. And it invested $150 million in CoreWeave, a cloud-computing firm.

Imco sold some of its stakes in infrastructure funds in the secondary market and may do the same in private equity funds in the future “to make room for direct investments or to commit to the fund manager’s next vintage,” Stoyanova said.

Office buildings and retail assets were 53 per cent of Imco’s property holdings as of Dec. 31, with a heavy tilt toward Canada.

IMCO, which inherited a big chunk of its property portfolio from the pension funds it assumed control of years ago, has been diversifying into European and U.S. real estate, according to Stoyanova. Last year, the pension fund disposed of around $1 billion in Canadian real estate assets. “Obviously in order to transform it, we need to dispose assets to get dry powder to buy new ones,” she said.