Debates about Columbus’ Spanish Jewish ancestry are not new − the claim was once a bid for social acceptance

(The Conversation) — Claims about Columbus being Sephardic have bubbled up for decades. Early in the 20th century, some immigrant groups hoped proving ties to him would improve their own social standing.

Devin Naar

October 28, 2024

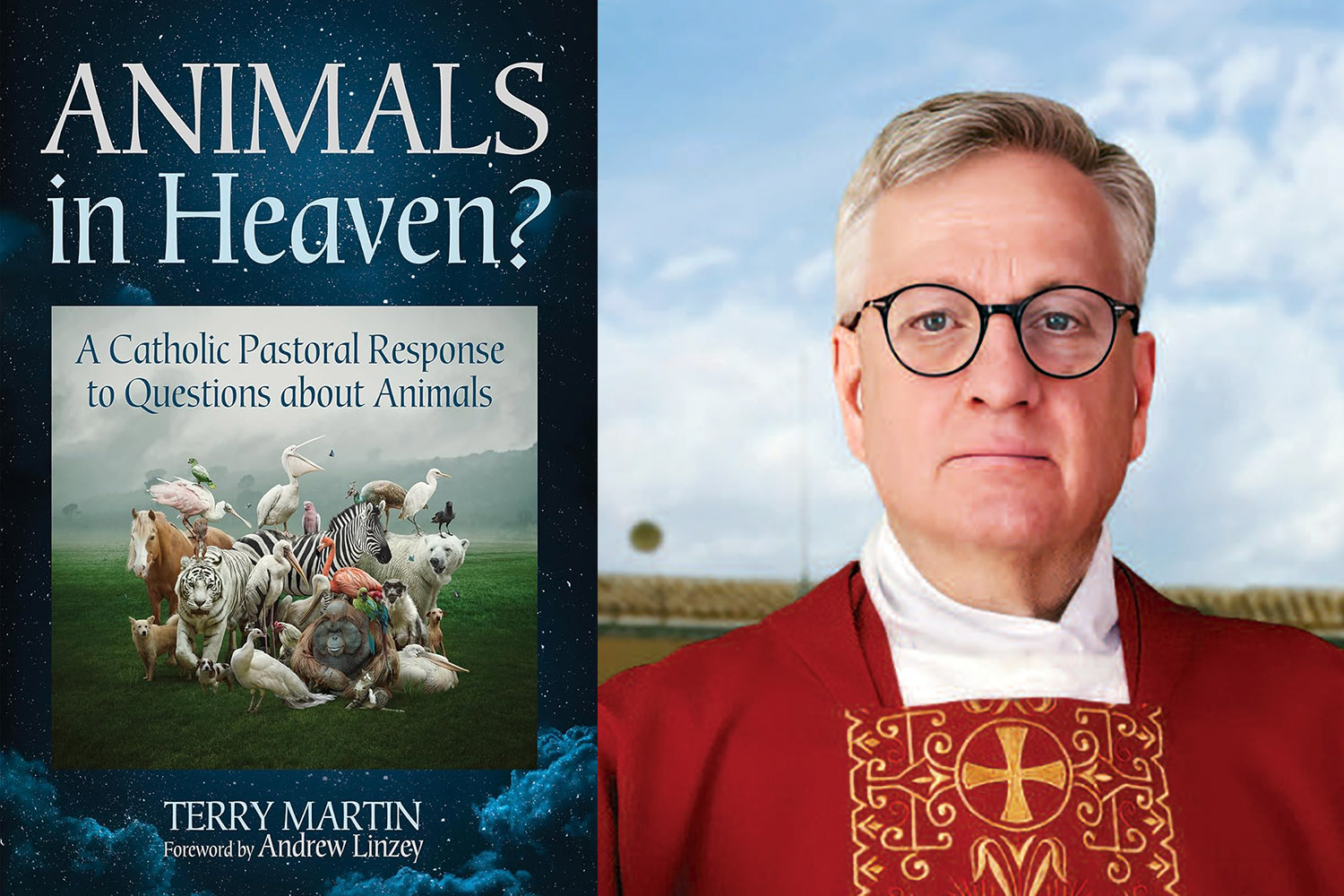

(The Conversation) — In connection to Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples Day, media from the BBC and Fox to Reuters and Haaretz reported on new DNA evidence about the holiday’s original namesake. According to research revealed in a recent Spanish documentary, Christopher Columbus was not Italian, as widely assumed, but Sephardic: of Spanish Jewish lineage.

About 1 in 5 people in Spain and Portugal today may indeed be of “converso” origin: descendants of Jews or Muslims who converted to Catholicism, often under threat of death or expulsion. Regardless of whether Columbus was genealogically Jewish, though, there is scant evidence that he considered himself to be Jewish in any meaningful way. After all, he wrote approvingly of the Spanish king and queen’s decision to expel Jews from Spain in 1492.

The claim that Columbus may have been of Spanish Jewish descent is by no means certain; the “new” research has not yet been published in any academic journals. What’s more, it’s far from new.

The debate over the origins of the New World’s “discoverer” stretch back more than a century, to a time when Columbus was more routinely hailed as a hero – whereas today, he is remembered as the man who initiated European settler colonialism in the Americas and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. For decades, some Spanish and American Jewish activists claimed that Columbus was a Sephardic Jew.

One of their own

At the turn of the 20th century, new immigrant groups in the U.S. were seeking acceptance as part of dominant white American society. Spaniards, Jews, Italians and Greeks seized claims that Columbus was one of their own, hoping to combat prejudice that they faced. By linking themselves to the progenitor of white “civilization” in the Americas, they sought to secure their own position on the white side of the color line, with the privileges and protections that status bestowed.

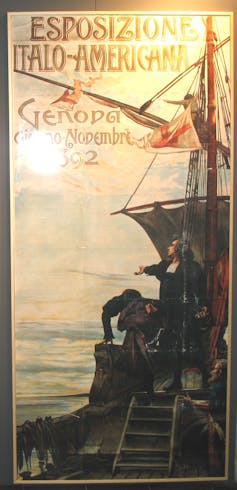

A poster for the Italian-American Exposition of 1892 in Genoa, Italy – often thought to be Columbus’ birthplace.

Twice25 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

U.S. President Benjamin Harrison instituted Columbus Day in 1892, initially as a one-time holiday. The event was meant to celebrate Italian American contributions to society – partly as an apology, following the lynching of 11 Italian immigrants in New Orleans. Decades later, in 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt rendered Columbus Day a federal holiday, even as the U.S. government continued to impose a quota on Italian immigration.

Early claims about Columbus or members of his entourage being Sephardic Jews also emerged in 1892 – the 400th anniversary of the conquerer’s arrival. Oscar Straus, a Jewish American diplomat, commissioned Meyer Kayserling, a rabbi and scholar, to research Jews’ role in the age of conquest. While Kayserling’s book did not say Columbus himself was of Jewish origin, it claimed that many people connected to his voyages were, including an interpreter named Luis de Torres and funder Luis de Santagel. Straus hoped that highlighting Jewish contributions to American society would curtail rising antisemitism in the United States.

Spanish strategy

In contrast, Spanish claims about Columbus as a Sephardic Jew sought to elevate Spain’s own international image. After its 1898 defeat in the Spanish-American War, Spain lost its possessions in the Western Hemisphere and ceased to be a major European colonial power. A cohort of Spanish writers and artists, known loosely as the Generation of ’98, produced an outpouring of cultural creativity grappling with Spain’s new position.

Some politicians and intellectuals drew on economic and cultural arguments to court descendants of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, whom they viewed as having preserved the Spanish language, and thus providing a new source of influence in the Mediterranean region. Ultimately, the Spanish government issued a decree in 1924 that rendered these descendants eligible for citizenship – an offer it renewed from 2015-2021.

Raquel Venitura and Moise Cohen were wed in Madrid in 1930, the first Hebrew marriage ceremony in Spain since the Inquisition.

Bettmann via Getty Images

Spanish intellectuals became the first to claim that Columbus was a Sephardic Jew, hoping to further elevate Spain’s status, in the wake of the losses of 1898, as the trailblazer of European civilization in the Americas. By World War I, scholar Celso Garcia de la Riega published a theory that not only some of Columbus’ crew had Spanish Jewish origins, but Columbus himself. Nobel Prize nominee Salvador de Madariaga endorsed the theory of Columbus’ Jewish origins in his 1940 book on Don Cristobal Colón.

Crucial moment

The rise of Nazism heightened discussion among American Jews about Columbus and brought Sephardic Jews themselves into the debate – hoping that a connection to the explorer would temper rising antisemitism.

Sephardic Jews also hoped that if Columbus were recognized as one of their own, Ashkenazi Jews, the dominant Jewish group in the United States, would be more likely to treat them with respect. Sephardic Jews coming from the Ottoman Empire – one of the primary places their ancestors sought refuge after Spain – were often maligned as “uncivilized” and “uncultured” due to their associations with the Muslim world.

As Spanish and Portuguese Jews were the first practicing Jews to come to the Americas, Sephardic Jews arriving from the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 20th century hoped to hitch their story to the grandeur of the country’s first Jewish communities.

In 1933, American Jewish writer Maurice David purported to offer Spanish archival evidence to demonstrate Columbus’ Spanish Jewish bona fides. While David was not Sephardic himself, the Sephardic Jewish community in New York advertised his book’s “sensational” claims in La Vara, a newspaper written in Ladino, the main Sephardic language, also called Judeo-Spanish.

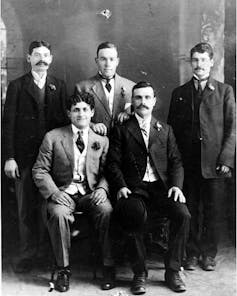

Sephardic men in Seattle, around 1918.

University of Washington via Wikimedia Commons

The most prominent Sephardic exponent of the theory was the former editor of La Amerika, the first Ladino newspaper published in the U.S. During the Second World War, Moise Gadol published a booklet in English called “Christopher Columbus was a Spanish-Jew.”

Gadol sought to elevate the status of his own community of Jews from the Ottoman Empire. By demonstrating links to Columbus, he hoped that all Sephardic Jews – not only those early Spanish and Portuguese Jews who came to the Americas during the colonial period – would be associated with Europe rather than the “Orient,” and with being “white” rather than “brown.”

Gadol also sought to exert pressure on the American public and government to loosen the quotas preventing Jews fleeing Nazi persecution from entering the United States. Two years before, in 1939, the government had rejected all 900 passengers aboard the SS St. Louis, who were forced to return to Europe – an infamous manifestation of the policy.

Gadol’s dubious claims about Columbus, however, did not produce the desired results. Sephardic Jews continued to be marginalized within the broader American Jewish community. Meanwhile, immigration quotas based on nationality – in effect until 1965 – continued to prevent Jewish refugees from finding safe haven in the U.S.

Then … and now

A century ago, embracing Columbus – and the sweeping colonization he represents – was a way for marginalized immigrant groups to claim a sense of belonging as part of the dominant white caste in American society.

Today, it provokes uncomfortable questions. especially claims about Columbus as a Jew. Fixating on his ancestry reinforces the racial blood logic of the Spanish Inquisition, according to which a person was considered Jewish or Muslim based on descent alone – to say nothing of the racial logic of Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow South.

What’s more, the emphasis on Columbus’ personal genealogy distracts from the actual geopolitical forces at play, such as empire building and resource extraction, that propelled Europe’s conquest and mass violence.

As discussions about antisemitism intensify in the U.S. and across the world, perhaps the idea that Columbus was “Jewish” – a conquistador who initiated the destruction of Indigenous peoples – only aggravates the problem.

(Devin Naar, Associate Professor of History and Jewish Studies and Chair of the Sephardic Studies Program, University of Washington. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)