Nicole Karlis, Salon

February 07, 2021

The presence of methane has long been a point of contention among Mars experts

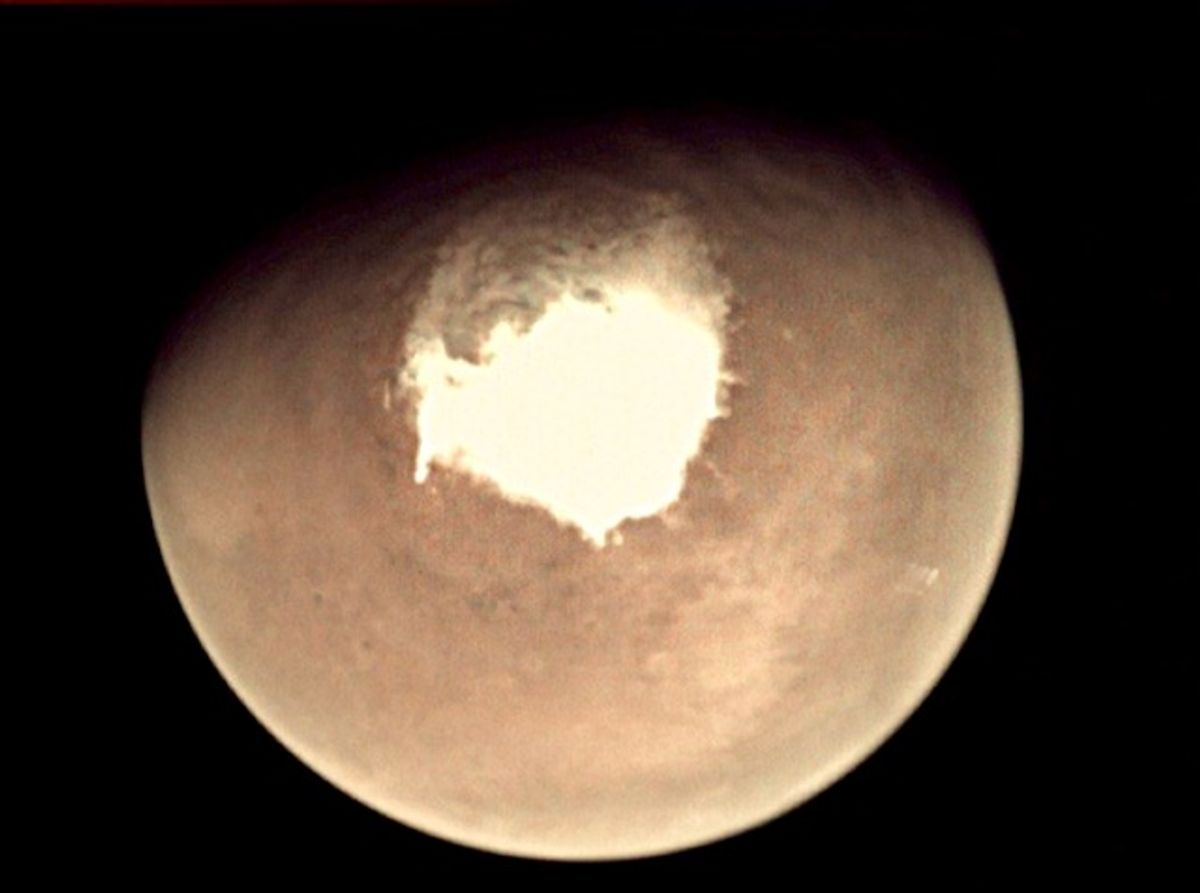

EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY/AFP/File / HO

On February 18, NASA's Perseverance rover will parachute through thin Martian air, marking a new era in red planet exploration. Landing on the Jezero Crater, which is located north of the Martian equator, will be no easy feat. Only about 40 percent of the missions ever sent to Mars succeed, according to NASA. If it does, Perseverance could drastically change the way we think about extraterrestrial life. That's because scientists believe Jezero, a 28 mile-wide impact crater that used to be a lake, is an ideal place to look for evidence of ancient microbial life on Mars.

Once it lands, Perseverance will collect and store Martian rock and soil samples, which will eventually be returned to Earth. This is known as a "sample-return mission," an extremely rare type of space exploration mission due to its expense. (Indeed, there has never been a sample return mission from another planet.) And once Martian soil is returned to Earth in a decade, scientists will set about studying the material to figure out if there was ever ancient life on Mars.

Yet some scientists believe that these samples could answer an even bigger question: Did life on Earth originate on Mars?

Though the idea that life started on Mars before migrating on Earth sounds like some far-fetched sci-fi premise, many renowned scientists take the theory seriously. The general idea of life starting elsewhere in space before migrating here has a name, too: Panspermia. It's the hypothesis that life exists elsewhere in the universe, and is distributed by asteroids and other space debris.

To be clear, the notion of life on Earth originating on Mars isn't a dominant theory in the scientific community, but it does appear to be catching on. And scientists like Gary Ruvkun, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, say that it does sound "obvious, in a way."

The evidence starts with how space debris moved around in the young solar system. Indeed, we have evidence of an exchange of rocks from Mars to Earth. Martian meteorites have been found in Antarctica and across the world — an estimated 159, according to the International Meteorite Collectors Association.

"You can assign them to Mars based on the gaseous inclusions that they have, that are sort of the equivalent of the gases that were shown by the Viking spacecraft" to exist in Mars' atmosphere, Ruvkun said. In other words, small bubbles of air in these rocks reveal that they were forged in the Martian air. "So, there is exchange between Mars and Earth — probably more often going from Mars to Earth because it goes 'downhill,' going to Mars is 'uphill,' gravitationally-speaking."

But for Ruvkun, whose area of expertise is genomics, it's the timing of cellular life that he believes makes a strong case that life on Earth came from somewhere else — perhaps Mars, or perhaps Mars vis-a-vis another planet.

Ruvkun noted that our genomes reveal the history of life, and provide clues about the ancestors that preceded us by millions or even billions of years. "In our genomes, you can kind of see the history, right?" he said. "There's the RNA world that predated the DNA world and it's very well supported by all kinds of current biology; so, we know the steps that evolution took in order to get to where we are now."

Thanks to the advancement of genomics, the understanding of LUCA (the Last Universal Common Ancestor) — meaning the organism from which all life on Earth evolved from — has greatly advanced. By studying the genetics of all organisms on Earth, scientists have a very good sense of what the single-celled ancestor of every living thing (on Earth) looked like. They also know the timeline: all modern life forms descend from a single-celled organism that lived about 3.9 billion years ago, only 200 million years after the first appearance of liquid water. In the grand scheme of the universe, that's not that long.

And the last universal common ancestor was fairly complicated as far as organisms go. That leaves two possibilities, Ruvkun says. "Either evolution to full-on modern genomes is really easy, or the reason you see it so fast was that we just 'caught' life, it didn't actually start here." He adds, "I like the idea that we just caught it and that's why it's so fast, but I'm an outlier."

If that's the case, then Erik Asphaug, is a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona, is also an outlier. Asphaug said that what we know about the oldest rocks on Earth — which have chemical evidence of carbon isotopes, tracing back to nearly 4 billion years ago — tell us that life started "started forming on Earth almost as soon as it was possible for it to happen."

If that's the case, it makes for an interesting precedent. "Let's say you expect life to be flourishing whenever a planet cools down to the point where it can start to have liquid water," Asphaug said. "But just looking at our own solar system, what planet was likely to be habitable first? Almost certainly Mars."

This is because, Asphaug said, Mars formed before Earth did. Early in Martian history when Mars was cooling down, Mars would have had a "hospitable" environment before Earth.

"If life was going to start anywhere it might start first on Mars," Asphaug said. "We don't know what the requirement is — you know, if it required something super special like the existence of a moon or some factors that are unique to the Earth — but just in terms of what place had liquid water first, that would have been Mars."

An intriguing and convincing piece of evidence relates to how material moved between the two neighboring planets. Indeed, the further you go back in time, the bigger the collisions of rocks between Mars and Earth, Asphaug said. These impact events could have been huge "mountain-sized blocks of Mars" that were launched into space. Such massive asteroids could serve as a home for a hardy microorganism.

"When you collide back into a planet, some fraction of that mountain-sized mass is going to survive as debris on the surface," he said. "It's taken a while for modeling to show that you can have a relatively intact survival of what we call 'ballistic panspermia' — firing a bullet into one planet, knocking bits off, and having it end up on another planet. But it's feasible, we think it happens, and the trajectory would tend to go from Mars to the Earth, much more likely than from Earth to Mars."

Asphaug added that surviving the trip, given the mass of the vehicle for the microorganisms, wouldn't be a problem — and neither would surviving on a new, hospitable planet.

"Any early life form would be resistant to what's going on at the tail end of planet formation," he said. "Any organism that's going to be existing has to be used to the horrific bombardment of impacts, even apart from this, swapping from planet to planet."

In other words, early microbial life would have been fine with harsh environments and long periods of dormancy.

Harvard professor Avi Loeb told Salon via email that one of the Martian rocks found on Earth, ALH 84001, "was not heated along its journey to more than 40 degrees Celsius and could have carried life."

All three scientists believe that Perseverance might be able to add credibility to the theory of panspermia.

"If you were to go and find remnants of life on Mars, which we hope to do with Perseverance rover and these other Martian adventures, I would be personally surprised if they were not connected at the hip to terrestrial life," Asphaug said.

Ruvkun said he hopes to be one of the scientists to look for DNA when the sample from Mars hopefully, eventually, returns.

"Launching something from Mars is a seriously difficult thing," he said.

But what would this mean for human beings, and our existential understanding of who we are and where we came from?

"In that case, we might all be Martians," Loeb said. He joked that the self-help book "Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus" may have been more right than we know.

Or perhaps, as Ruvkun believes, we're from a different solar system, and life is just scattering across the universe.

"To me the idea that it all started on Earth, and every single solar system has their own little evolution of life happening, and they're all independent — it just seems kind of dumb," Ruvkun said. "It's so much more explanatory to say 'no, it's spreading, it's spreading all across the universe, and we caught it too, it didn't start here," he added. "And in this moment during the pandemic — what a great moment to pitch the idea. Maybe people will finally believe it."

On February 18, NASA's Perseverance rover will parachute through thin Martian air, marking a new era in red planet exploration. Landing on the Jezero Crater, which is located north of the Martian equator, will be no easy feat. Only about 40 percent of the missions ever sent to Mars succeed, according to NASA. If it does, Perseverance could drastically change the way we think about extraterrestrial life. That's because scientists believe Jezero, a 28 mile-wide impact crater that used to be a lake, is an ideal place to look for evidence of ancient microbial life on Mars.

Once it lands, Perseverance will collect and store Martian rock and soil samples, which will eventually be returned to Earth. This is known as a "sample-return mission," an extremely rare type of space exploration mission due to its expense. (Indeed, there has never been a sample return mission from another planet.) And once Martian soil is returned to Earth in a decade, scientists will set about studying the material to figure out if there was ever ancient life on Mars.

Yet some scientists believe that these samples could answer an even bigger question: Did life on Earth originate on Mars?

Though the idea that life started on Mars before migrating on Earth sounds like some far-fetched sci-fi premise, many renowned scientists take the theory seriously. The general idea of life starting elsewhere in space before migrating here has a name, too: Panspermia. It's the hypothesis that life exists elsewhere in the universe, and is distributed by asteroids and other space debris.

To be clear, the notion of life on Earth originating on Mars isn't a dominant theory in the scientific community, but it does appear to be catching on. And scientists like Gary Ruvkun, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, say that it does sound "obvious, in a way."

The evidence starts with how space debris moved around in the young solar system. Indeed, we have evidence of an exchange of rocks from Mars to Earth. Martian meteorites have been found in Antarctica and across the world — an estimated 159, according to the International Meteorite Collectors Association.

"You can assign them to Mars based on the gaseous inclusions that they have, that are sort of the equivalent of the gases that were shown by the Viking spacecraft" to exist in Mars' atmosphere, Ruvkun said. In other words, small bubbles of air in these rocks reveal that they were forged in the Martian air. "So, there is exchange between Mars and Earth — probably more often going from Mars to Earth because it goes 'downhill,' going to Mars is 'uphill,' gravitationally-speaking."

But for Ruvkun, whose area of expertise is genomics, it's the timing of cellular life that he believes makes a strong case that life on Earth came from somewhere else — perhaps Mars, or perhaps Mars vis-a-vis another planet.

Ruvkun noted that our genomes reveal the history of life, and provide clues about the ancestors that preceded us by millions or even billions of years. "In our genomes, you can kind of see the history, right?" he said. "There's the RNA world that predated the DNA world and it's very well supported by all kinds of current biology; so, we know the steps that evolution took in order to get to where we are now."

Thanks to the advancement of genomics, the understanding of LUCA (the Last Universal Common Ancestor) — meaning the organism from which all life on Earth evolved from — has greatly advanced. By studying the genetics of all organisms on Earth, scientists have a very good sense of what the single-celled ancestor of every living thing (on Earth) looked like. They also know the timeline: all modern life forms descend from a single-celled organism that lived about 3.9 billion years ago, only 200 million years after the first appearance of liquid water. In the grand scheme of the universe, that's not that long.

And the last universal common ancestor was fairly complicated as far as organisms go. That leaves two possibilities, Ruvkun says. "Either evolution to full-on modern genomes is really easy, or the reason you see it so fast was that we just 'caught' life, it didn't actually start here." He adds, "I like the idea that we just caught it and that's why it's so fast, but I'm an outlier."

If that's the case, then Erik Asphaug, is a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona, is also an outlier. Asphaug said that what we know about the oldest rocks on Earth — which have chemical evidence of carbon isotopes, tracing back to nearly 4 billion years ago — tell us that life started "started forming on Earth almost as soon as it was possible for it to happen."

If that's the case, it makes for an interesting precedent. "Let's say you expect life to be flourishing whenever a planet cools down to the point where it can start to have liquid water," Asphaug said. "But just looking at our own solar system, what planet was likely to be habitable first? Almost certainly Mars."

This is because, Asphaug said, Mars formed before Earth did. Early in Martian history when Mars was cooling down, Mars would have had a "hospitable" environment before Earth.

"If life was going to start anywhere it might start first on Mars," Asphaug said. "We don't know what the requirement is — you know, if it required something super special like the existence of a moon or some factors that are unique to the Earth — but just in terms of what place had liquid water first, that would have been Mars."

An intriguing and convincing piece of evidence relates to how material moved between the two neighboring planets. Indeed, the further you go back in time, the bigger the collisions of rocks between Mars and Earth, Asphaug said. These impact events could have been huge "mountain-sized blocks of Mars" that were launched into space. Such massive asteroids could serve as a home for a hardy microorganism.

"When you collide back into a planet, some fraction of that mountain-sized mass is going to survive as debris on the surface," he said. "It's taken a while for modeling to show that you can have a relatively intact survival of what we call 'ballistic panspermia' — firing a bullet into one planet, knocking bits off, and having it end up on another planet. But it's feasible, we think it happens, and the trajectory would tend to go from Mars to the Earth, much more likely than from Earth to Mars."

Asphaug added that surviving the trip, given the mass of the vehicle for the microorganisms, wouldn't be a problem — and neither would surviving on a new, hospitable planet.

"Any early life form would be resistant to what's going on at the tail end of planet formation," he said. "Any organism that's going to be existing has to be used to the horrific bombardment of impacts, even apart from this, swapping from planet to planet."

In other words, early microbial life would have been fine with harsh environments and long periods of dormancy.

Harvard professor Avi Loeb told Salon via email that one of the Martian rocks found on Earth, ALH 84001, "was not heated along its journey to more than 40 degrees Celsius and could have carried life."

All three scientists believe that Perseverance might be able to add credibility to the theory of panspermia.

"If you were to go and find remnants of life on Mars, which we hope to do with Perseverance rover and these other Martian adventures, I would be personally surprised if they were not connected at the hip to terrestrial life," Asphaug said.

Ruvkun said he hopes to be one of the scientists to look for DNA when the sample from Mars hopefully, eventually, returns.

"Launching something from Mars is a seriously difficult thing," he said.

But what would this mean for human beings, and our existential understanding of who we are and where we came from?

"In that case, we might all be Martians," Loeb said. He joked that the self-help book "Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus" may have been more right than we know.

Or perhaps, as Ruvkun believes, we're from a different solar system, and life is just scattering across the universe.

"To me the idea that it all started on Earth, and every single solar system has their own little evolution of life happening, and they're all independent — it just seems kind of dumb," Ruvkun said. "It's so much more explanatory to say 'no, it's spreading, it's spreading all across the universe, and we caught it too, it didn't start here," he added. "And in this moment during the pandemic — what a great moment to pitch the idea. Maybe people will finally believe it."

No comments:

Post a Comment