Do Insects Have Brains?

BY ORLANDO JENKINSON ON 3/1/22

There are an estimated 10 quintillion (10,000,000,000,000,000,000) insects alive on Earth, making them one of the planet's most abundant creatures. The biggest known insect, the giant weta, weighed in at 71g, while the smallest is a type of parasitic wasp that measures just 0.005 inches in length.

But do these tiny creatures have brains inside their tiny heads?

The short answer is yes—and they may contain hidden depths of intelligence that the scientists are only beginning to understand.

There are an estimated 10 quintillion (10,000,000,000,000,000,000) insects alive on Earth, making them one of the planet's most abundant creatures. The biggest known insect, the giant weta, weighed in at 71g, while the smallest is a type of parasitic wasp that measures just 0.005 inches in length.

But do these tiny creatures have brains inside their tiny heads?

The short answer is yes—and they may contain hidden depths of intelligence that the scientists are only beginning to understand.

What are insect brains like?

Lars Chittka, a professor in sensory and behavioral ecology at Queen Mary University of London, U.K., told Newsweek insects have "beautifully elaborate" brains.

"They differ from mammalian brains in many ways. One of the most obvious ones is that they are smaller. But they are not necessarily less complex or sophisticated.

"The networks in insect brains can be extremely finely branched and complex. The pattern might be as advanced as a fully-grown oak tree. Every individual cell can contact up to 10,000 other brain cells. So the computational network of insect brains can be very complex.

"They are smaller and more accessible for neuroscientists. But we're very far from understanding them comprehensively because even though it's easier than say a human brain to study it's still far too complex at the present stage to understand in its entirety."

How intelligent are insects?

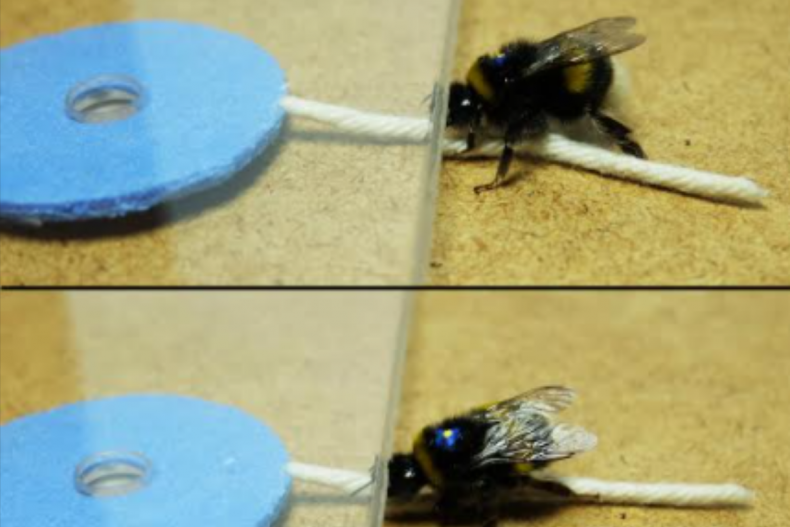

Bees pull string for reward in a scientific experiment. Professor Lars Chittka said the study showed behavior akin to tool use.

SYLVAIN ALEM AND LARS CHITTKA

Scientists have known for 100 years that insects can learn things. For example, we know insects that have homes—such as ants, bees and wasps—can travel miles away from their base and find their way back again.

There are also cases of what appears to be conscious decision-making among some insects.

"Bees, for example, have to be very intelligent shoppers in the flower supermarket," Chittka said. "Different flowers offer different qualities and quantities of nectar and pollen and bees are very good at learning about the rewards to be expected in flower species and then associate their colors, patterns and odors that flowers display, memorize them and use that as predictors of rewards."

Scientists have also carried out intelligence tests on insects that had previously been used on primates and birds.

"We discovered that bees count landmarks between their hive and their food source," Chittka said. "Bees can be trained to recognize images of human faces. More recently we've trained them to manipulate objects in a manner equivalent to tool use.

"Bees learnt to pull strings to gain access to a reward that was visible but not accessible. Moreover they could learn such skills by learning from each other. An individual trained with that skill could spread that learning to an entire population."

Research has also shown intelligence in other insect species. Ants, for example, move around using various different "modules" of their brains, including one dedicated to retracing their steps or backtracking. Ants have also been found to use tools to transport liquid food to their colony by soaking materials in the food and taking it back for later consumption.

One study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B showed complex social behavior in paper wasps. The insects were found to recognize individuals in their colony, appreciate attributes such as relative strength associated with a particular wasp and form social hierarchies based on that knowledge.

Scientists have known for 100 years that insects can learn things. For example, we know insects that have homes—such as ants, bees and wasps—can travel miles away from their base and find their way back again.

There are also cases of what appears to be conscious decision-making among some insects.

"Bees, for example, have to be very intelligent shoppers in the flower supermarket," Chittka said. "Different flowers offer different qualities and quantities of nectar and pollen and bees are very good at learning about the rewards to be expected in flower species and then associate their colors, patterns and odors that flowers display, memorize them and use that as predictors of rewards."

Scientists have also carried out intelligence tests on insects that had previously been used on primates and birds.

"We discovered that bees count landmarks between their hive and their food source," Chittka said. "Bees can be trained to recognize images of human faces. More recently we've trained them to manipulate objects in a manner equivalent to tool use.

"Bees learnt to pull strings to gain access to a reward that was visible but not accessible. Moreover they could learn such skills by learning from each other. An individual trained with that skill could spread that learning to an entire population."

Research has also shown intelligence in other insect species. Ants, for example, move around using various different "modules" of their brains, including one dedicated to retracing their steps or backtracking. Ants have also been found to use tools to transport liquid food to their colony by soaking materials in the food and taking it back for later consumption.

One study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B showed complex social behavior in paper wasps. The insects were found to recognize individuals in their colony, appreciate attributes such as relative strength associated with a particular wasp and form social hierarchies based on that knowledge.

Could insects be conscious?

Studies have shown the animals exhibit various signs of intelligence from tool use to emotionality.

BIGMIKEPHOTO/GETTY IMAGES

While amazing, these behaviors could be compared to machine learning—even facial recognition is now the domain of everyday machines like smartphones.

But could insect intelligence incorporate consciousness?

While there is no straightforward test to define consciousness in animals other than humans, evidence increasingly suggests it exists in other species. Even insects.

Chittka and his colleagues conducted experiments on bees that suggested the animals could feel optimistic.

Other researchers have also found evidence of something approaching consciousness in other insects.

Christof Koch, from the California Institute of Technology, told Discover Magazine he stopped killing insects needlessly after learning more about their intelligence. He also said there was a chance some insects such as cockroaches and bees could be conscious due complex formations known as mushroom structures in their brains, which are key to memory formation and processing experiences.

"Probably what consciousness requires is a sufficiently complicated system with massive feedback. Insects have that. If you look at the mushroom bodies, they're massively parallel and have feedback," he told the website.

The next frontier for insect intelligence is now exploring states of consciousness and emotions in the animals.

"If we use the same indicators of emotional states as commonly accepted in domesticated animals, then these qualify as indicators of emotional states," Chittka said. "That indicates that there might be a sentience. But we're putting more pieces of the puzzle together."

While amazing, these behaviors could be compared to machine learning—even facial recognition is now the domain of everyday machines like smartphones.

But could insect intelligence incorporate consciousness?

While there is no straightforward test to define consciousness in animals other than humans, evidence increasingly suggests it exists in other species. Even insects.

Chittka and his colleagues conducted experiments on bees that suggested the animals could feel optimistic.

Other researchers have also found evidence of something approaching consciousness in other insects.

Christof Koch, from the California Institute of Technology, told Discover Magazine he stopped killing insects needlessly after learning more about their intelligence. He also said there was a chance some insects such as cockroaches and bees could be conscious due complex formations known as mushroom structures in their brains, which are key to memory formation and processing experiences.

"Probably what consciousness requires is a sufficiently complicated system with massive feedback. Insects have that. If you look at the mushroom bodies, they're massively parallel and have feedback," he told the website.

The next frontier for insect intelligence is now exploring states of consciousness and emotions in the animals.

"If we use the same indicators of emotional states as commonly accepted in domesticated animals, then these qualify as indicators of emotional states," Chittka said. "That indicates that there might be a sentience. But we're putting more pieces of the puzzle together."

No comments:

Post a Comment