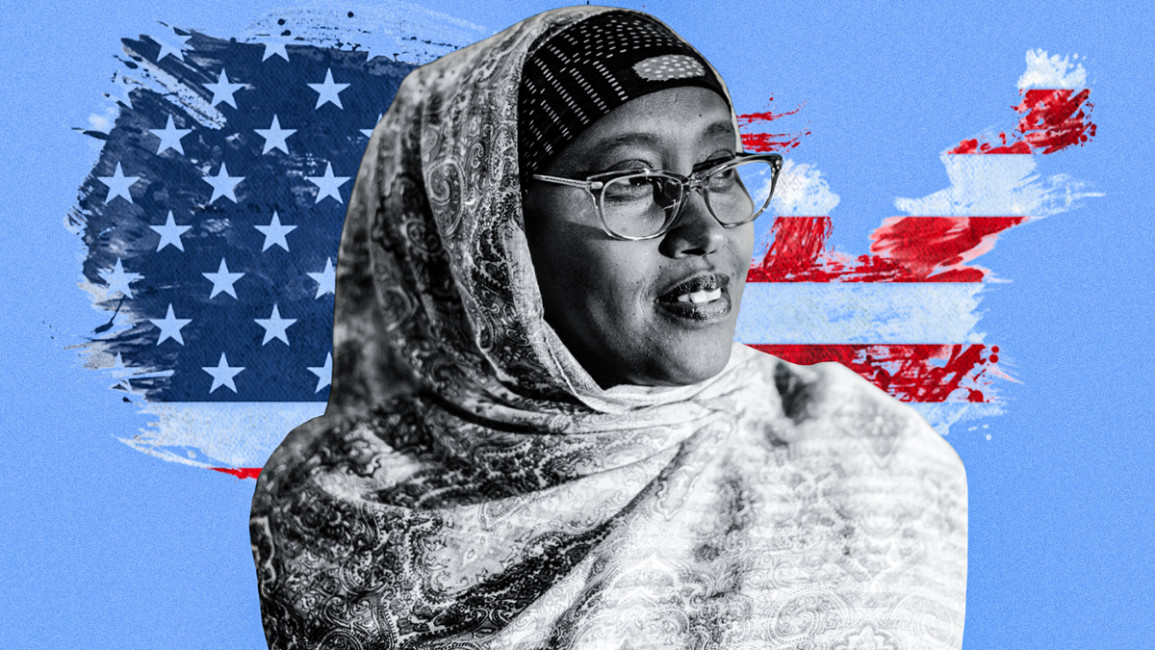

America's first Somali mayor Deqa Dhalac hopes to inspire immigrants, youths and women

Interviews

Brooke Anderson

Washington, D.C.

01 April, 2022

Brooke Anderson

Washington, D.C.

01 April, 2022

The New Arab Meets: Deqa Dhalac, who has long worked behind the scenes in politics. Now, as mayor, she hopes to make a difference as the face of South Portland, Maine.

When Deqa Dhalac became mayor of South Portland, Maine at the end of last year, making her what is believed to be America’s first Somali American mayor, it was after many years of working to make a difference, starting with her upbringing in her country of origin.

“My parents were a big part of my growing up, telling me to do the right thing, and always wanting us to have a space to say what we had to say,” Deqa tells The New Arab. "Our government was repressive. My father would tell us that other countries have democracies and people would elect who they wanted.”

RELATEDSocietySheeffah Shiraz

She was raised in an educated family that encouraged her to learn languages, history and politics, skills that would be useful after she left for a new life in the United States in 1990, just prior to the civil war.

Deqa says she wants the state's next governor to be encouraging of immigrants, support diversity,

and to show good will toward Maine's immigrants [Getty]

Finally arriving in 1992, after a trip that took her from Mogadishu to Rome – where she spent nearly two months at an airport as she sought asylum– to the UK, then to Canada, and then finally to Atlanta, where she became a permanent US resident.

"My parents were a big part of my growing up, telling me to do the right thing, and always wanting us to have a space to say what we had to say"

There, she quickly got to work in grassroots political organising, registering people to vote and teaching them about the importance of being politically engaged.

But with all the advantages Atlanta had as a big city, its fast pace eventually took its toll, leaving her with little time for herself.

“Atlanta is a big city, and my children were very small. I would do my work and I would do community organising, and before I knew it, the week was up,” she recalls. “I always wanted to do more, but I didn’t have enough time.”

and to show good will toward Maine's immigrants [Getty]

Finally arriving in 1992, after a trip that took her from Mogadishu to Rome – where she spent nearly two months at an airport as she sought asylum– to the UK, then to Canada, and then finally to Atlanta, where she became a permanent US resident.

"My parents were a big part of my growing up, telling me to do the right thing, and always wanting us to have a space to say what we had to say"

There, she quickly got to work in grassroots political organising, registering people to vote and teaching them about the importance of being politically engaged.

But with all the advantages Atlanta had as a big city, its fast pace eventually took its toll, leaving her with little time for herself.

“Atlanta is a big city, and my children were very small. I would do my work and I would do community organising, and before I knew it, the week was up,” she recalls. “I always wanted to do more, but I didn’t have enough time.”

RELATEDInterviewsSarah Essa

After her uncle moved to Maine in 2004, he told her she would have more time for herself there.

“Is there a place like that in the US? And you’ll still have time for yourself?” she asked herself, as she thought about continuing her education. She would eventually earn two master’s degrees at universities in the northeast.

When she visited her uncle, she liked the small-town feel with few distractions. The following year, in 2005, she moved up to Maine, a state known more for its cold climate and ageing population than for its political activism. Nevertheless, she continued with her community organising and dove into local politics in South Portland, a city of around 25,000.

"Unfortunately, not everyone welcomed the state’s new residents with open arms. In 2002, Lewiston Mayor Robert MacDonald wrote an open letter, telling Somalis not to come"

Maine, America’s whitest state, was a major shift from Atlanta, a hub for African American culture, and even further from her original home of Somalia. Yet, around the time she moved there, a growing African – mainly Somali – community was taking shape, reflected in the state’s food and arts scene, and increasingly in its politics.

Like her, many had been through hard times, having fled violence and having lived in multiple locations, and they were looking for a quiet place to settle down and raise their children.

Unfortunately, not everyone welcomed the state’s new residents with open arms. In 2002, Lewiston Mayor Robert MacDonald wrote an open letter, telling Somalis not to come. This was followed by demonstrations of support for the African immigrants, an important statement of solidarity as Deqa was settling into her life in Maine.

“The youth can really take a look at those of us from other countries. They can see it doesn’t matter what colour skin they have. They can do this,” she says. “They’re the future. They need to step up and be part of civic engagement. There’s so much attack on democracy, with voter suppression and women’s rights. They need to step up and take up spaces.”The state’s small but growing population of young African immigrants marks a contrast from its long-time ageing white population, a change that Deqa hopes will inspire local youths to become more politically engaged.

After working largely behind the scenes in various social work positions, in 2018 she was elected to the city council of South Portland, where she worked across the spectrum in small city government.

"The youth can really take a look at those of us from other countries. They can see it doesn’t matter what colour skin they have. They can do this... They’re the future"

“I was just helping folks behind the scenes registering to vote. I never wanted to run for office. It never occurred to me,” she recalls thinking at the time. “People said it would be great. And I said: No, not me. Because of the identities I hold: being a woman, black, immigrant and Muslim – especially during Trump’s time during the Muslim ban.” Then she thought, “Let’s just show folks who are saying this, immigrants are doing good work.”

“The youth can really take a look at those of us from other countries. They can see it doesn’t matter what colour skin they have. They can do this,” she says. “They’re the future. They need to step up and be part of civic engagement. There’s so much attack on democracy, with voter suppression and women’s rights. They need to step up and take up spaces.”The state’s small but growing population of young African immigrants marks a contrast from its long-time ageing white population, a change that Deqa hopes will inspire local youths to become more politically engaged.

After working largely behind the scenes in various social work positions, in 2018 she was elected to the city council of South Portland, where she worked across the spectrum in small city government.

"The youth can really take a look at those of us from other countries. They can see it doesn’t matter what colour skin they have. They can do this... They’re the future"

“I was just helping folks behind the scenes registering to vote. I never wanted to run for office. It never occurred to me,” she recalls thinking at the time. “People said it would be great. And I said: No, not me. Because of the identities I hold: being a woman, black, immigrant and Muslim – especially during Trump’s time during the Muslim ban.” Then she thought, “Let’s just show folks who are saying this, immigrants are doing good work.”

Deqa Dhalac points to members of the audience during a ceremony in the Lecture Hall at South Portland High School in December after she was formally seated as mayor of South Portland, Maines [Getty]

She was re-elected in 2020. Then last year, there was an opening to run for mayor. Encouraged by her colleagues, she took the plunge. Though this position was voted on by the councillors, she took the opportunity to get to know the community she hoped to represent by knocking on around 2,000 doors.

She got support from New American Leaders, an organisation that helps people with immigrant backgrounds run for elected office, whom she met through Portland, Maine's Vice Mayor Pious Ali, part of the state’s growing contingency of immigrant politicians.

“I never wanted to run for office... People said it would be great. And I said: No, not me. Because of the identities I hold: being a woman, black, immigrant and Muslim – especially during Trump’s time during the Muslim ban"

“Becoming the first Somali American mayor in the United States, Deqa Dhalac is paving the way for other immigrant and BIPOC leaders and changing the face of leadership,” Megan Cagle, director of communications at New American Leaders, tells The New Arab.

“Much like Congresswoman Ilhan Omar and other Somali American elected officials, as a Black Muslim woman, Deqa challenges outdated and discriminatory ideas of who can and should serve in public office.”

She was re-elected in 2020. Then last year, there was an opening to run for mayor. Encouraged by her colleagues, she took the plunge. Though this position was voted on by the councillors, she took the opportunity to get to know the community she hoped to represent by knocking on around 2,000 doors.

She got support from New American Leaders, an organisation that helps people with immigrant backgrounds run for elected office, whom she met through Portland, Maine's Vice Mayor Pious Ali, part of the state’s growing contingency of immigrant politicians.

“I never wanted to run for office... People said it would be great. And I said: No, not me. Because of the identities I hold: being a woman, black, immigrant and Muslim – especially during Trump’s time during the Muslim ban"

“Becoming the first Somali American mayor in the United States, Deqa Dhalac is paving the way for other immigrant and BIPOC leaders and changing the face of leadership,” Megan Cagle, director of communications at New American Leaders, tells The New Arab.

“Much like Congresswoman Ilhan Omar and other Somali American elected officials, as a Black Muslim woman, Deqa challenges outdated and discriminatory ideas of who can and should serve in public office.”

RELATEDPerspectivesNegar Mortazavi

In the end, she was voted in unanimously, a testament to her commitment to the local government and the confidence of her colleagues.

“It’s the most beautiful thing I ever did,” she says. “Having people from all parts of the world, doing good work and running for office. It’s just something to be really proud of.”

Brooke Anderson is The New Arab's correspondent in Washington DC, covering US and international politics, business and culture

Follow her on Twitter: @Brookethenews

No comments:

Post a Comment