A new novel explores a post-pandemic religious world — in the 14th century

Peter Manseau’s latest book examines the Black Death for clues to our cultural moment.

(RNS) — One million deaths and counting. It’s unfathomable, really — both the fact that the pandemic has stolen so many lives, and that American culture has mostly moved on.

How could we have rebounded so quickly when every 330th American is now dead from this virus?

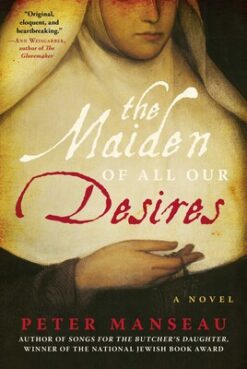

For insights I turn to historians, and one in particular who is also, helpfully, a novelist. Peter Manseau, founding director of the Smithsonian’s Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History, is also an award-winning novelist whose most recent work of fiction, “The Maiden of All Our Desires,” takes place in Europe 20 years after the Black Death has ravaged the population.

Set in a convent that possesses a secret book of near-scripture containing the wisdom sayings of its founder, Sister Ursula, it focuses on the tensions between different kinds of religious authority. There’s also a generation gap: Those who survived the plague are still scarred by their memories of it, while the blithe young adults around them can’t relate.

This Zoom interview has been edited for length and clarity. — JKR

This novel was 25 years in the making. Where did it come from?

Novelist Peter Manseau

This was the first book I ever tried to write. I was an undergraduate and it was a four-page short story for a creative writing class, about a nun in a convent who fell in love with the wind. As a thesis, I expanded it to 100 pages. The idea followed me in my 20s and 30s, and it gradually developed into this kernel of a story about a generation after the plague.

It wasn’t until 2020 that I thought (the story) could allow me to write about many of the things we were all grappling with in the early days of the pandemic, without making it explicitly about COVID-19. I didn’t want to write about our own pandemic, but I felt like it presented a universal set of questions that could be approached through a story set in a time far different from our own, and yet so resonant: What does it mean to live through a plague, and what comes next? What happens for the generation that only vaguely remembers the plague, that lives with it as only a story?

Your kids are old enough to remember this time. What will this memory be like for them?

That’s why I wanted to have a kind of a folkloric or mythical frame around this story. It opens with the coming of a storm, which in the moment reshapes the world, but in the future is only this vaguely remembered thing. And that, I have been imagining, is what will happen with COVID-19. Fairly quickly, this moment that we’ve lived through, which upended everything in 2020 and 2021, will be in the rearview mirror. It may become a “remember when” in a matter of years rather than of decades, as I frame it in the novel.

So I’m interested in the way that these events that are disruptive in a daily, unignorable way become stories that are told. I’m fascinated by the act of making a story of catastrophe. I recently wrote a piece in Slate about the many uses we have made of the Black Death during COVID and the way our thinking about it has evolved.

How has it evolved?

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, articles would claim that the Black Death that killed half the population of Europe in the 1340s and 1350s may have had a bright side, in that it led to the Renaissance and the Reformation — that it changed labor practices and shifted authority in medieval Europe. As we were entering into this pandemic, which had (already) killed tens of thousands of people, we were desperate for the understanding that this might all work out OK.

It’s interesting to me, particularly as someone who writes about religion, to see in real time this desire to turn catastrophe into redemptive story. That impulse is obviously at the heart of so many religious traditions: “This terrible thing happened. But what does it mean for us? How can we grow from it?”

More recently, we have lost patience for that as the numbers rose. Even though we’re still nowhere near the loss that humanity suffered during the Black Death, it’s become more difficult to make those silver-lining arguments about a two-year-long pandemic with a million Americans dead.

Your novel features a crisis of authority about whether the convent should build a wall to keep out the plague. That certainly felt timely.

“The Maiden of All Our Desires” by Peter Manseau. Courtesy image

Probably my first return to this story after so many years was in the early days of the Trump administration when we were all talking about the building of walls and the fear of outsiders coming in. That was when I began adding in this dimension of a wall being built around this convent that hadn’t had a wall before because it was open to the world.

There’s a pivotal scene in which a sister has been instructed by the convent’s priest not to open the gates to strangers. But the abbess overrules him, saying that they’ve never rejected the Rule of St. Benedict before and shouldn’t begin due to the threat of plague.

I’m interested in the collision of different types of religious authority. So that is a moment when it’s really dramatized: the sacramental authority of the priest on the one hand and the local, relational authority of the abbess on the other hand. When they inevitably come into conflict in the story, there’s a real taking of sides. It splinters the community.

What is next for you in terms of your writing?

My next book is narrative nonfiction that’s set in a 19th-century almshouse in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, the town where I grew up. A poorhouse and lunatic asylum built mainly to house immigrant Irish was alleged to be actively starving and maltreating its patients and letting them die — for the sake, it seems, of selling their bodies to medical schools. In the 1880s it was the biggest public health scandal in the country.

It’s a fantastically dark story, and what’s interesting to me is that for the most part, no one remembers this in the town. The only part of the story that some people will know is that Anne Sullivan, the teacher of Helen Keller, was a patient at the Tewksbury Almshouse as a child. Her brother died there, but she was eventually able to escape.

When I was in high school and I ran on the cross-country team, we ran through the woods at the foot of the hill where the state hospital is. Those woods were full of bodies, thousands of unmarked graves. Literally running over graves and not knowing what is just beneath your feet is a metaphor for uncovering this history, which may be my own attempt to turn catastrophe into a story.

More RNS content about Peter Manseau:

State of the art: A Q&A with the Smithsonian’s new religion curator

New theory connects a Native American prophet with Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

No comments:

Post a Comment