On April 8, 1952, U.S. President Harry Truman ordered government seizure of the steel industry to avoid a general strike.

Steel Strike of 1952

Background

From 1950-1953, the United States was involved in the Korean War. To fund the war, Truman originally wanted to increase taxes and implement credit controls to limit inflation. Many Americans were opposed to this due to the previous two decades of shortages from the Great Depression and World War II rationing, so the government was forced to get creative in thinking of other ways to fund and mobilize for war. The Office of Price Stabilization (OPS) enacted price controls on various wartime industries, including steel tonnage pricing, while the Wage Stabilization Board (WSB) worked to limit wage increases for workers to what they felt was a reasonable amount. With these two major agencies, the US was able to keep producing war materials without interruption from labor and industry disputes over prices and wages.

As time went on, slight changes had to be made to the wartime economy. Taxes ultimately had to be increased over time, but wages were increasing too slowly to please many of the labor groups in the US. This situation especially upset the steel unions. The steel industry was vital to the war effort, and the steel unions were strong. They wanted to capitalize on their importance to the defense efforts by granting wage increases to steel workers. By late 1951 the unions were asking for wage increases above the 10% maximum set by the Wage Stabilization Board. The companies told the unions that they would not allow these wage increases unless they could guarantee a higher sale price for the steel they were producing. After several round of negotiations, the Office of Price Stabilization still did not agree to the tonnage hike the steel companies wanted, so the companies denied the wage increases demanded by the unions. The unions threatened to strike, and a domestic crisis began. Truman immediately threw his support behind the union workers, as they were some of his biggest political supporters. However, he found himself in a precarious political situation.

The threat of a strike continued throughout early 1952. In March, the WSB recommended the steelworkers be granted a wage increase. Worrying that their profit margins would drop if they paid their workers more money, the steel companies asked the OPS for an increase in steel tonnage pricing. The OPS refused the proposed price increase and made a lower counteroffer, angering the steel companies. In the midst of these arguments, the workers decided to strike. With important supplies for the war effort hanging in the balance, Truman had to determine what to do.

It is within the president's power to put people back to work through strikes, but there are different ways to go about it. For instance, in 1917 President Wilson nationalized the railroad industry to keep workers from striking during WWI. Truman could do something similar via Executive Order, but he had other options as well. In 1947 Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which banned strategies to help workers organize unions and limited the president's power to seize industries during times of labor unrest. Instead, it offered the president the power to force workers back to work for 80 days while negotiations continued between labor and management. This option would keep wartime industries running uninterrupted. In 1948, an amendment was added to the Selective Service Act, allowing the president to seize industry facilities that were unable to fill their government orders for wartime products. The steel industry was not defaulting on its order obligations; however, as commander-in-chief, the president can make all military decisions for the United States, including mobilization efforts.

In the end, Truman issued Executive Order 10340 to seize control of the steel industries on April 8, 1952. The companies sued, resulting in a Supreme Court case to determine whether or not Truman overstepped his Constitutional powers in the steel seizures.

Key Question

Did Truman overstep his Constitutional powers in seizing the steel industries in 1952?

Materials

Documents to be examined:

- Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Need for Government Opreation of the Steel Mills, April 8, 1952

- Letter from Harold Enarson to the President, May 8, 1952

- Political Cartoon “We’re Waiting to Hear from the Principal,” May 24, 1952

- Telegram from George Fehlman to the President, April 9, 1952

- The Constitutional Issues in the Steel Case, April 26, 1952

- Letter from Harry Truman to Supreme Court Justice William O’Douglas, July 9, 1952

- Executive Order 10340, Directing the Secretary of Commerce to Take Possession of and Operate the Plants and Facilities of Certain Steel Companies, April 8, 1952

Handouts

David Adler

June 11, 2022

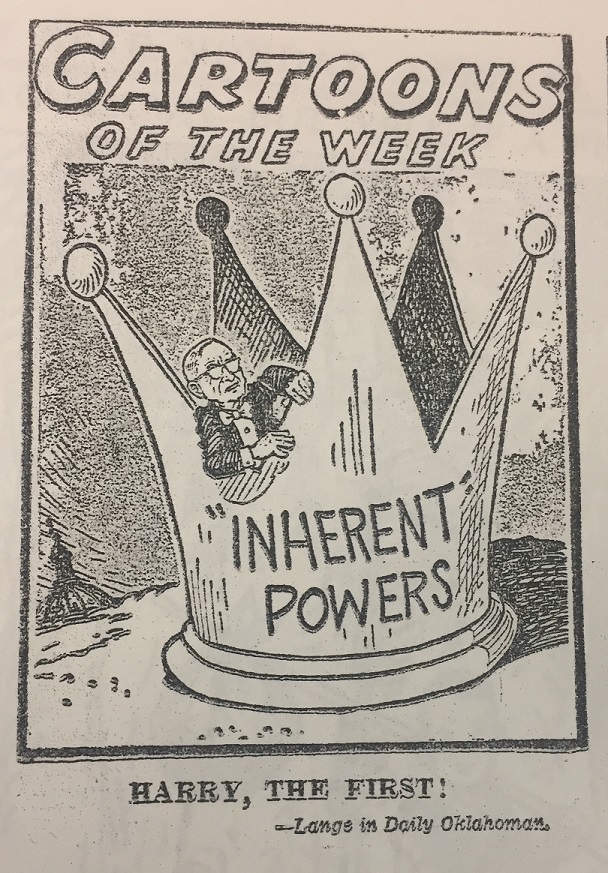

In his 6-3 opinion for the Supreme Court in the landmark case, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), Justice Hugo Black rejected President Harry Truman’s assertion of an inherent executive power to seize the steel industry as a means of thwarting a nationwide steel strike. Black’s opinion, a historic rebuke to sweeping claims of presidential authority, provided a textbook lesson on the constraining force of the separation of powers doctrine and why it prohibited President Truman from issuing an executive order that encroached on legislative power.

President Truman, it will be recalled, had ordered Secretary of Commerce Charles Sawyer to seize the steel industry for the purpose of ensuring the continuation of steel production which he believed critical to both the United States’ role in the Korean War and the task of rebuilding Europe in the aftermath of World War II. Justice Black declared that the president’s power, “if any, to issue the order must stem from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.”

Black proceeded to emphasize that no statute existed that “expressly” authorized Truman’s act, nor was there any law from which such power “can be fairly implied.” Consequently, Black noted, the “necessary authority must be found in some provision of the Constitution.” But Truman made no such claim. Instead, he asserted the aggregate of his powers under the Constitution, with reliance on the Vesting Clause, the Take Care Clause and the Commander in Chief Clause.

Black easily disposed of the Commander in Chief argument and trained his sights on the president’s assertion of an inherent power. He denied that the seizure order could be upheld by the “grant of executive power to the president.” As Black explained it, “In the framework of our Constitution, the President’s power to see that the laws are faithfully executed refutes the idea that he is to be a lawmaker.” The Constitution, he stated, grants to Congress, not the president, the authority to make laws.

At bottom, Congress had not authorized the president to seize private property. That fact is what united the five separate concurring opinions. While the concurring opinions written by the majority emphasized different aspects of the separation of powers, the common denominator lay in the justices’ insistence on the existence of law granting seizure authority to the president.

The majority agreed, moreover, that the president possessed no “inherent” power to seize the steel mills. The assertion of such a vague, undefined reservoir of “inherent” power, variously characterized as an emergency or prerogative power, would permit the president to act in the absence of law and even in defiance of it. In that case, the president might displace the laws of Congress, thus mortally wounding the separation of powers, which insists that the nation should be governed by known rules of law. That principle can be maintained, however, only if those who make the law have no power to execute it and those who execute it have no power to make it. That critical distinction would be eviscerated by an inherent executive power.

The Truman administration’s assertion of an “inherent” power to confront a crisis raised the profile of Youngstown to a historic level. It harkened back to one of the most fundamental, dramatic and transcendent issues in the long history of Anglo-American jurisprudence: subordinating the executive to the rule of law. The issue of the president’s relationship to the law defined the Steel Seizure Case and confronted the justices of the Supreme Court with an issue that judges have grappled with since the great English judge, Sir Edward Coke, in 1608, boldly declared to an outraged King James I that the king is indeed subject to the law.

The administration’s assertion of an emergency executive power to take any action the president believed would serve the national welfare, hadn’t been heard in an English-speaking courtroom since the mid-17th Century reign of King Charles I. While the Court rejected the claim of a presidential prerogative power, there lingered the question of which branch of government possessed the authority to meet and resolve an emergency. After all, it is not possible for Congress to write laws to govern every conceivable emergency that might arise. And it is scarcely imaginable that a government could stand idly by in the face of a crisis that threatens lives and the future of the nation simply because it had not occurred to the legislature to act. In other words, the problem of emergency could not be wished away or relegated to the confines of an academic seminar. If the president does not possess a constitutionally based emergency power, then the question arises: What is the constitutional prescription for meeting an emergency? The framers’ answer lay in resort to the ancient doctrine of retroactive ratification, which we explain in our next column.

No comments:

Post a Comment