How Marine Heat Waves Affect the Ocean - And What Can Be Done

As we enter El Niño, periods of surging temperatures at sea are predicted to grow more frequent and intense.

[By Emma Bryce]

On 4 July 2023, the World Meteorological Organization declared the beginning of an El Niño phase, a climate pattern that drives up temperatures across land and sea.

Past weather events provide clues about what extreme temperatures could mean for the ocean. For instance, in December 2010, a wave of unusually warm water swept across the luxuriant and biodiverse seagrass meadows of Australia’s Shark Bay. In a matter of days, it destroyed a third of the habitat, unthreading the delicate seagrass quilt and, over the next three years, releasing between 2 and 9 billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere. “The losses there were phenomenal,” says Kathryn Smith, a researcher with the UK’s Marine Biological Association.

Scientists call the event a “marine heatwave”, meaning a period of exceptionally high water temperature that starts suddenly and continues for days to months, distinguishing it from long-term warming trends. Like heatwaves on land that threaten terrestrial ecosystems, heatwaves at sea harm marine life, posing “a clear and present threat to the systems we depend on,” says Sarah Cooley, director of climate science at the Ocean Conservancy.

These impacts are expected to grow. The UN’s climate science body, the IPCC, projects that by 2100 marine heatwaves will be up to 50-fold more frequent, and 10-fold more intense compared to pre-industrial times. Scientists are now developing ways to forecast these events. Their research can feed into measures that mitigate the threats for vulnerable habitats, species, and the coastal communities that depend on them.

What are the impacts of heatwaves?

The ocean absorbs 90% of the excess heat caused by greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere. On top of this, climate change is amping up weather conditions that inject even more heat into the planet’s largest ecosystem.

One of these is high-pressure systems. While low-pressure systems bring cool, cloudy air that draws heat out of the ocean, attracting colder, nutrient-rich waters to the surface, high-pressure systems disrupt these. They bring warmer, windless, cloudless conditions in which the sun can heat the water unimpeded. Fewer nutrients rise to the water’s surface to support the base of the marine food chain, such as krill and phytoplankton.

In 2014, these factors combined to create a gigantic sauna in the North Pacific. Hundreds of kilometres wide and 6C warmer than average, it was known as “the Blob.” The sudden displacement of nutrients spelled disaster for fish, seabirds, and cetaceans who had to migrate elsewhere to find food, or simply starved.

By the time the Blob had dissipated, an estimated one million seabirds had died, along with countless crustaceans, fish and seals. A record number of whales became entangled in fishing gear when searching for food closer to shore.

Warm water surges can also make conditions unbearable in sensitive hubs of biodiversity like seagrass meadows, coral reefs, and kelp beds. Compared to general ocean warming, heatwaves lead to faster bleaching, more coral death, and the decimation of kelp forests. Higher water temperatures also trigger suffocating algal blooms that drive large scale die-offs of marine life.

For instance, kelp forests along a 100km stretch of western Australia were erased by the same heatwave that destroyed the Shark Bay seagrass fields in 2010. “That was 12 years ago, and the kelp hasn’t returned,” says Smith, whose primary research focus is marine heatwaves.

What causes these events?

Scientists are still unpicking the meteorological triggers behind these phenomena, but they are linked to anthropogenic climate change. One hypothesis is that as the Arctic warms – three times faster than the planetary average – its temperature difference with the tropics is reduced. Svenja Ryan, a physical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, explains that this reduction might weaken the jet stream that usually pushes a band of rain and wind around the centre of the planet. The air current then becomes more vulnerable to intrusion by high pressure systems, which block usual atmospheric processes and form hovering hot air islands over land and sea.

The changes in the strength and direction of ocean currents could also trigger marine heatwaves, as some of the currents are transporting warm water to regions that they didn’t before.

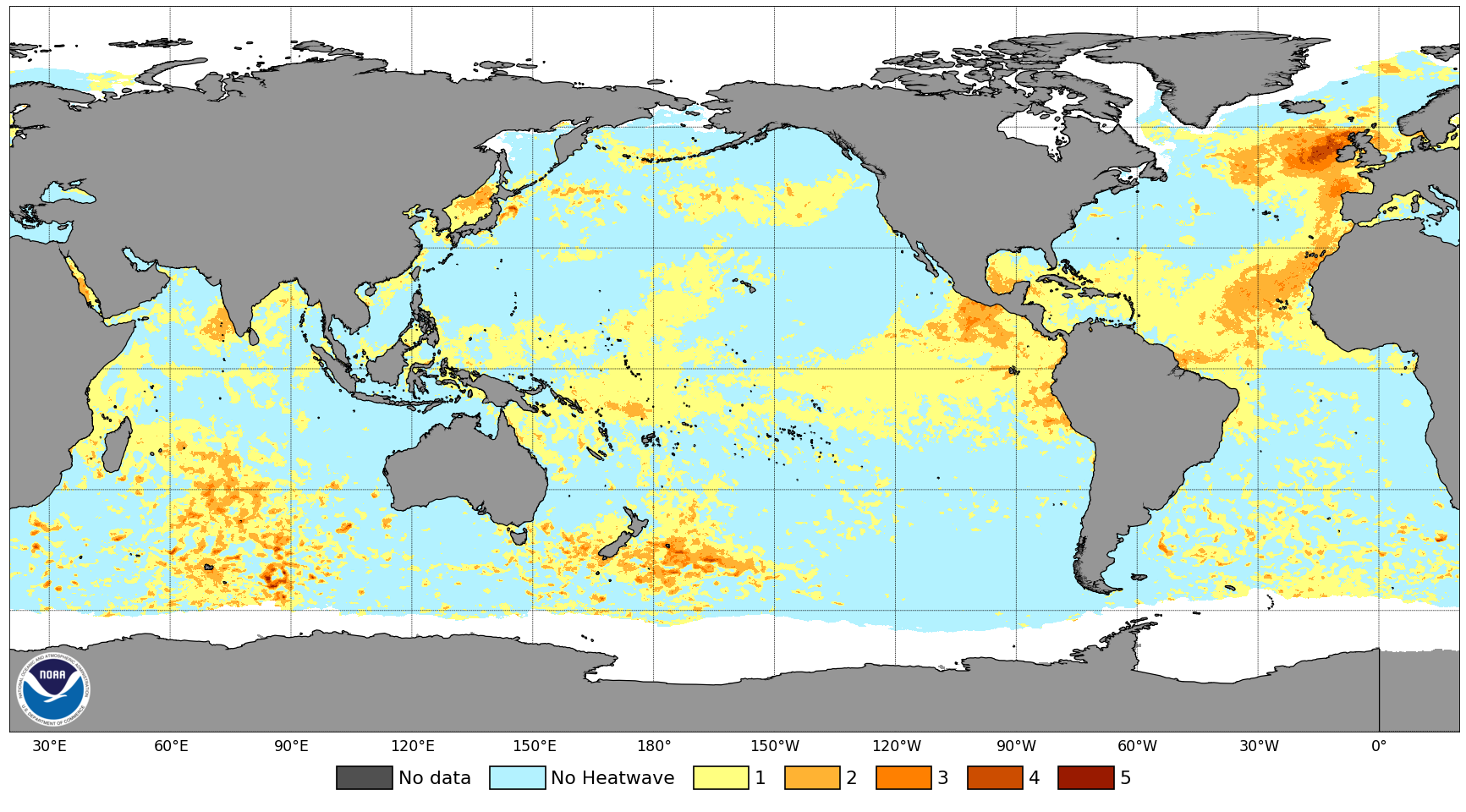

Sea surface temperature anomalies recorded on 19 June 2023. The cluster of red and orange at top right shows the record-breaking marine heatwave that hit the north-east Atlantic in late June. (Image: NOAA Marine Heatwave Watch)

Sea surface temperature anomalies recorded on 19 June 2023. The cluster of red and orange at top right shows the record-breaking marine heatwave that hit the north-east Atlantic in late June. (Image: NOAA Marine Heatwave Watch)

What are the costs of hotter seas?

Comparisons against historical datasets show that the number of marine heatwave days has increased by 54% since 1925, and eight of the hottest 10 on record have occurred in the last 13 years. “They are happening, they are really intense in certain regions, and they can really impact local communities and also economies,” Ryan says.

This socioeconomic toll is increasingly visible. Smith of the UK’s Marine Biological Association says: “There are lots of coastal communities who are losing their entire income in one hit from marine heatwaves.”

After the Blob, the Gulf of Alaska’s cod fishery, worth $100 million annually, collapsed. A 2016 heatwave off Chile’s coast triggered a toxic algal bloom that destroyed 20% of the country’s salmon farming production for the year, and cost the industry $800 million. Meanwhile, a survey shows that if general ocean warming continues and coral bleaching worsens in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the country will suffer $1 billion in lost tourism.

Increasingly popular carbon credit schemes that depend on intact seagrass meadows and kelp forests may also be undermined by marine heatwaves, Smith explains. Her research shows that 34 ocean heatwaves over the last 25 years have in fact cost several billion dollars annually in lost fisheries, tourism, and carbon storage. Harder to measure is the lost cultural value caused by heatwaves, and their contribution to extreme weather events like hurricanes.

How to adapt to heatwaves?

To stop excessive heat warming our oceans at root, we need to cut greenhouse gas emissions. But Cooley says it will take a while for the effects of decarbonisation to show. “We have so much heating that’s sort of ‘locked in’, and [in the meantime] the heatwaves will be getting worse and more extreme,” she explains. “But we know that we can decrease the other things under our control.”

Strengthening ecosystem resilience gives environments and their inhabitants the best chance of surviving warmer seas, Cooley says. Therefore, measures like reducing pollution and protecting more habitats like kelp beds and seagrass meadows can help mitigate the risks of marine heatwaves. “Having a large bank of a healthy ecosystem is still an insurance policy for us,” she adds.

Meanwhile, there’s a growing effort to forecast marine heatwaves, as we do those on land. The nascent science still requires more research looking into how these phenomena influence ocean currents, chemistry and food availability, and even how deep into the sea heatwaves reach. This knowledge is essential if we are to match the predictive precision we have on land.

But research suggests that under certain meteorological conditions, we could forecast some marine heatwaves up to a year in advance, says Michael Jacox, an oceanographer at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and lead author on the study that developed this estimate.

“I think the real crux of [forecasting] is in the translation to impacts, and then decision-making,” Jacox adds. More detailed information on when and where marine heatwaves will roll in creates room to adapt. Conservationists could pinpoint habitats in their path, and perhaps even introduce measures to shield them against the worst of the warming. Fishers could switch to less-threatened species, or move aquaculture pens out of harm’s way. Where livelihoods are threatened, forecasts could trigger financial support for communities most affected. Ideally, proactive national policies that recognise the reality of marine heatwaves would guide and support the interventions.

Today, Shark Bay’s seagrass meadows still bear the scars of the 2010 heatwave. Many ecosystems will face a similar threat from an increasingly febrile ocean, especially if events like El Niño heap more heat pressure onto it. Smith of the UK’s Marine Biological Association says: “We can’t save it all, so what do we try and protect? It’s about learning what the change is, and where the focus needs to be.”

Emma Bryce is a freelance journalist who covers stories focused on the environment, conservation and climate change. You can tweet her at @EmmaSAanne and read more at www.emmabryce.com.

This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Corals Are Beginning to Bleach as Oceans Hit Record Temperatures

The water off South Florida is over 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 Celsius) in mid-July, and scientists are already seeing signs of coral bleaching off Central and South America. Particularly concerning is how early in the summer we are seeing these high ocean temperatures. If the extreme heat persists, it could have dire consequences for coral reefs.

Just like humans, corals can handle some degree of stress, but the longer it lasts, the more harm it can do. Corals can’t move to cooler areas when water temperatures rise to dangerous levels. They are stuck in it. For those that are particularly sensitive to temperature stress, that can be devastating.

I lead the Coral Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Lab in Miami, Florida. Healthy coral reef ecosystems are important for humans in numerous ways. Unfortunately, marine heat waves are becoming more common and more extreme, with potentially devastating consequences for reefs around the world that are already in a fragile state.

Why coral reefs matter to everyone

Coral reefs are hot spots of biodiversity. They are often referred to as the rainforests of the sea because they are home to the highest concentrations of species in the ocean.

Healthy reefs are vibrant ecosystems that support fish and fisheries, which in turn support economies and food for millions of people. Additionally, they provide billions of dollars in economic activity every year through tourism, particularly in places like the Florida Keys, where people go to scuba dive, snorkel, fish and experience the natural beauty of coral reefs.

If that isn’t enough, reefs also protect shorelines, beaches and billions of dollars in coastal infrastructure by buffering wave energy, particularly during storms and hurricanes.

What goes into a coral reef?

But corals are quite sensitive to warming water. They host a microscopic symbiotic algae called zooxanthella that photosynthesizes just like plants, providing food to the coral. When the surrounding waters get too warm for too long, the zooxanthellae leave the coral, and the coral can turn pale or white – a process known as bleaching.

If corals stay bleached, they can become energetically compromised and ultimately die.

When corals die or their growth slows, these beautiful, complex reef habitats start disappearing and can eventually erode to sand. A recent paper by John Morris, a scientist in my lab in Florida, shows that around 70% of reefs are now net erosional in the Florida Keys, meaning they are losing more habitat than they build.

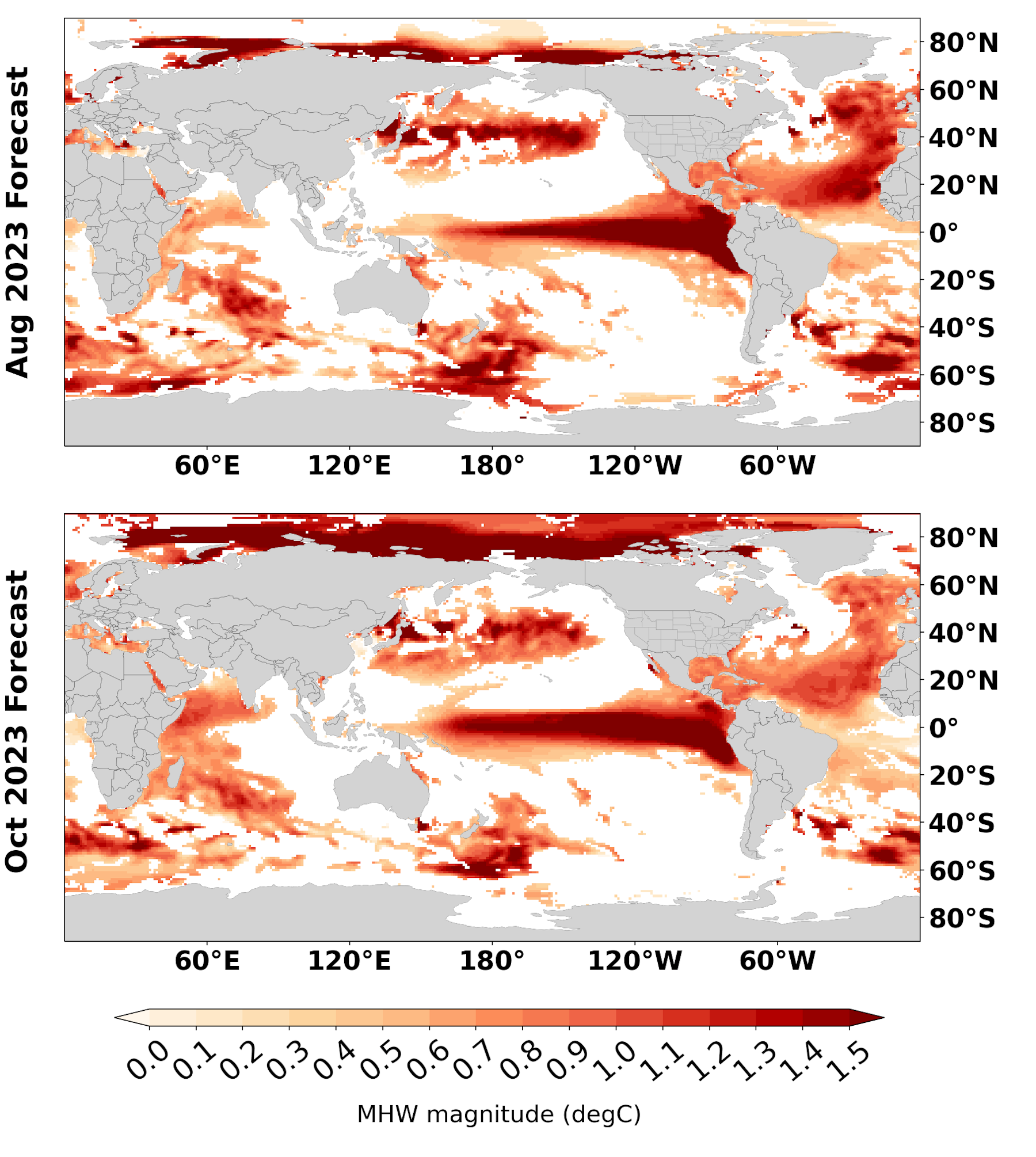

About 40% of the global ocean was experiencing a marine heat wave in July 2023. NOAA’s experimental forecasts for August and October show sea surface temperatures well above average in many regions. An increase of 1 degree Celsius = 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit. NOAA PSL

About 40% of the global ocean was experiencing a marine heat wave in July 2023. NOAA’s experimental forecasts for August and October show sea surface temperatures well above average in many regions. An increase of 1 degree Celsius = 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit. NOAA PSL

Unfortunately, these critical coral reef habitats are in decline around the world because of extreme bleaching events, disease and numerous other human-caused stressors. In the Florida Keys, coral cover has decline by about 90% over the past several decades.

Coral bleaching in 2023

In the Port of Miami, where we have found particularly resilient coral communities, a doctoral candidate in my lab, Allyson DeMerlis, documented the first coral bleaching of her experimentally outplanted corals on July 11, 2023.

Other scientists we work with have reported coral bleaching off of Colombia, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Mexico in the eastern Pacific, as well as along the Caribbean coasts of Panama, Mexico and Belize.

We have yet to see widespread coral death associated with this particular marine heat wave, so it is possible the corals could recover if sea surface temperatures cool down soon. However, global sea surface temperatures are at record highs, and large parts of the Atlantic and eastern Pacific are under bleaching alerts. At this point, the evidence points to the potential for a very negative outcome.

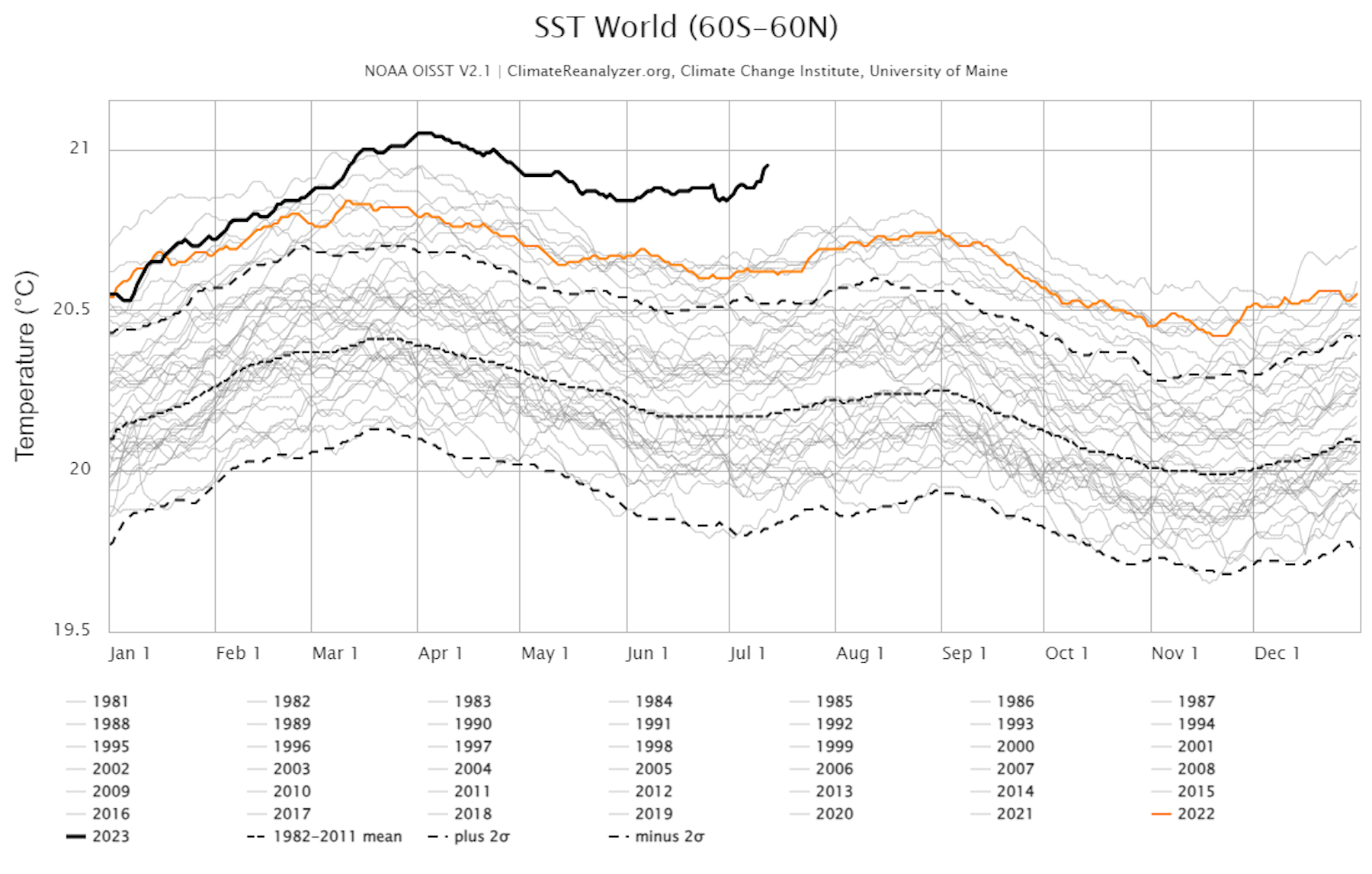

Sea surface temperatures have been off the charts. The thick black line is 2023. The orange line is 2022. The 1982-2011 average is the middle dashed line. ClimateReanalyzer.org/NOAA OISST v2.1

El Niño is contributing to the problem this year, but the longer-term trends of rising ocean heat are driven by global warming fueled by human activities.

To put that into context, a paper by NOAA scientist Derek Manzello showed that in the Florida Keys, the number of days per year in which water temperatures were higher than 90 F (32 C) had increased by more than 2,500% in the two decades following the mid-1990s relative to the prior 20 years. That is a remarkable increase in the number of days that corals are experiencing particularly stressful warm water.

What can we do to protect corals?

First, we cannot give up on corals.

Alice Webb, a coral reef scientist working with our group, recently published a study based on years of our research in the Florida Keys. She modeled reef habitat persistence under climate, restoration and adaptation scenarios and found that protecting reefs is going to take everything – active restoration of reefs, helping corals acclimate or adapt to changing temperatures, and, importantly, human curbing of greenhouse gas emissions.

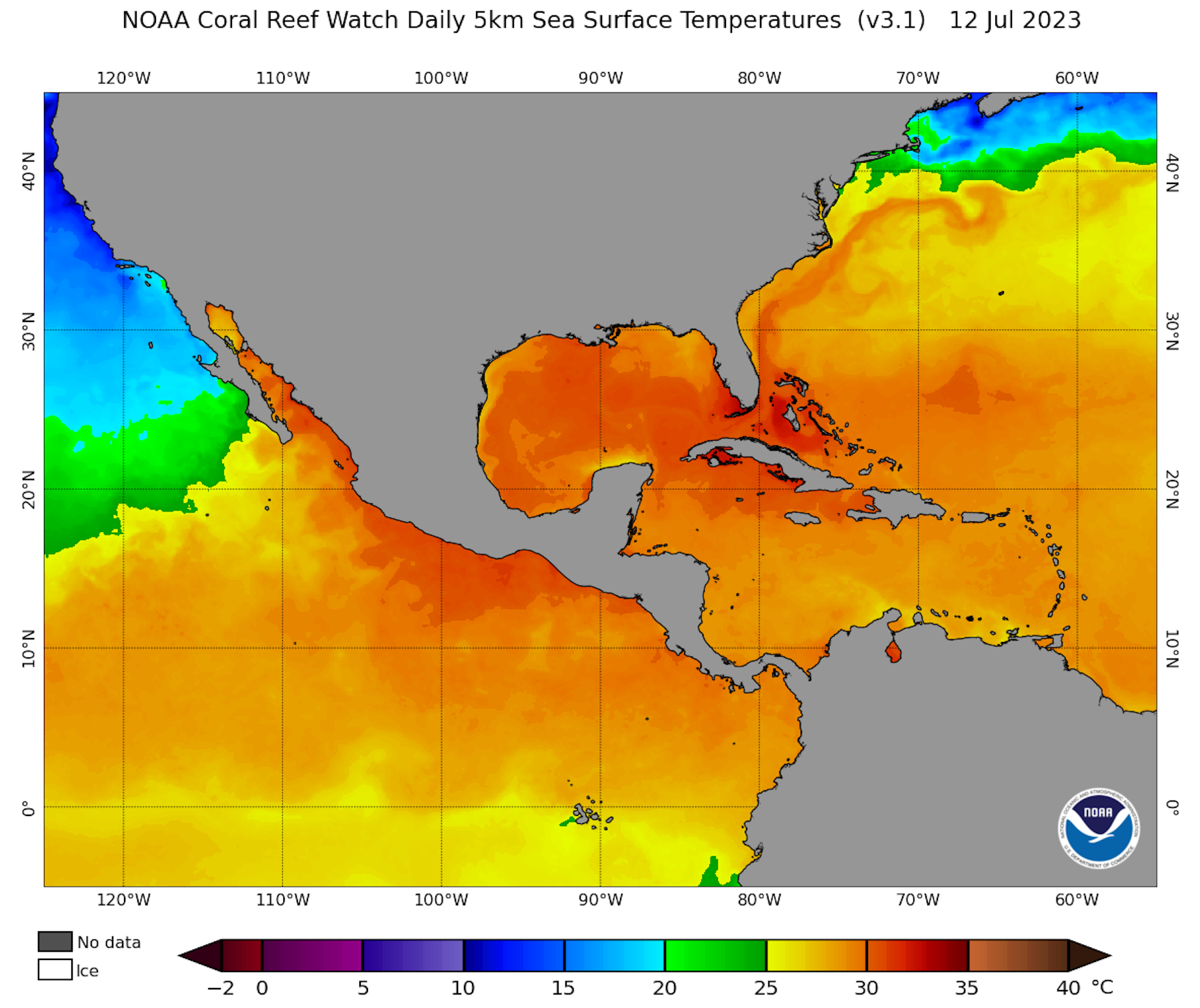

Sea surface temperatures off South Florida were abnormally high in mid-July 2023. Coral Reef Watch/NOAA

Sea surface temperatures off South Florida were abnormally high in mid-July 2023. Coral Reef Watch/NOAA

Major restoration efforts are underway in the Florida Keys as part of the NOAA-led Mission Iconic Reefs. We are also assessing how different coral individuals perform under stress, hoping to identify those that are particularly stress-tolerant by combing through the massive amounts of data from restoration projects and coral nurseries.

We are also evaluating stress-hardening techniques. For example, in tide pools, corals are exposed to large swings in temperature over short periods, making them more resilient to subsequent thermal stress events. We are exploring whether it’s possible to replicate that natural process in the lab, before corals are planted onto reefs, to better prepare them for stressful summers in the wild.

Coral bleaching on a large scale has really been documented only since the early 1980s. When I talk to people who have been fishing and diving in the Florida Keys since before I was born, they have amazing stories of how vibrant the reefs used to be. They know firsthand how bad things have become because they have lived it.

There isn’t currently a single silver-bullet solution, but ignoring the harm being done is not an option. There is simply too much at stake.

Ian Enochs is a Research Ecologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

This article appears courtesy of The Conversation and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment