Elena Kagan’s scathing Chevron dissent highlights US supreme court’s disregard for precedent

The court is turning into ‘an administrative czar’, says liberal justice after 40-year-old doctrine is overturned

Elena Kagan issued a devastating dissent to the decision of her hard-right fellow supreme court justices to overturn the Chevron doctrine that has been a cornerstone of federal regulation for 40 years, accusing the majority of turning itself into “the country’s administrative czar”.

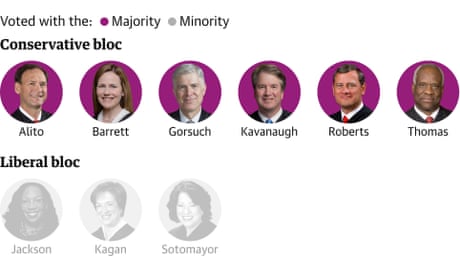

Kagan was joined by her two fellow liberal-leaning justices, Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson, in delivering a withering criticism of the actions of the ultra-right supermajority that was created by Donald Trump. Such caustic missives have become commonplace from the three outnumbered liberals, with each carefully crafted dissent sounding more incensed and despairing than the last.

US supreme court strikes down 40-year precedent, reducing power of federal agencies

In a speech at Harvard last month, Sotomayor revealed that after some of the supreme court’s recent decisions she has gone back to her office, closed the door and cried.

“There have been those days, and there are likely to be more,” she said.

Kagan’s dissent in Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo on Friday was the literary equivalent of crying over 33 pages. But she was also searingly angry.

She said that in one fell swoop, the rightwing majority had snatched the ability to make complex decisions over regulatory matters away from federal agencies and awarded the power to themselves.

A rule of judicial humility gives way to a rule of judicial hubrisElena Kagan, in her dissent

“As if it did not have enough on its plate, the majority turns itself into the country’s administrative czar,” she wrote.

For 40 years, she wrote, the Chevron doctrine, set out by the same supreme court in a 1984 ruling, had supported regulatory efforts by the US government by granting federal experts the ability to make reasonable decisions where congressional law was ambiguous. She gave a few examples of the work that was facilitated as a result, such as “keeping air and water clean, food and drugs safe, and financial markets honest”.

Now, the hard-right supermajority had flipped that on its head.

Instead of federal experts adjudicating on all manner of intricate scientific and technical questions – such as addressing the climate crisis, deciding on the country’s healthcare system or controlling AI – now judges would make those critical calls.

Kagan, displaying no desire to pull her punches, portrayed Friday’s ruling as a blatant power grab by the chief justice, John Roberts, and his five ultra-right peers, three of whom were appointed by Trump – Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Not for the first time, her most caustic comments relate to stare decisis – the adherence to legal precedent that is the foundation stone of the rule of law. Respect for the previous judgments of the supreme court is a reminder to judges that “wisdom often lies in what prior judges have done. It is a brake on the urge to convert every new judge’s opinion into a new legal rule or regime.”

By contrast, she went on: “It is impossible to pretend that today’s decision is a one-off, in its treatment of precedent.”

It has become an unquestionable pattern: the new hard-right supermajority has a fondness for tearing up their own court’s precedents stretching back decades. They did it when they eviscerated the right to an abortion in 2022, upending 50 years of settled law; they did it again last year when they prohibited affirmative action in university admissions, casting out 40 years of legal precedent; and now they’ve done it once more after 40 years to Chevron.

“Just my own defenses of stare decisis, my own dissents to this court’s reversals of settled law, by now fill a small volume,” Kagan said, her final words as plaintive as they were defiant.

The case of Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo Secretary of Commerce considered the regulation of fishing. The petitioners challenged the decision of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to require the petitioners to pay for observers required under a fishery management plan. They argued that the NMFS did not act within its mandate from the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA).

The Supreme Court did not decide on the facts of Loper. However, these facts provided an ambiguity in legislation through which the court could overrule the Chevron deference and remand Loper for further proceedings. In Chevron, the court found that “the Administrator’s interpretation… is entitled to deference” when it involves technical and complex reasoning to reconcile conflicting policies. The Loper court disagreed, finding that “Chevron was a judicial invention that required judges to disregard their statutory duties.”

In reaching this conclusion, the court analyzed the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), legislation that determines the role of courts. The court found that the Chevron deference conflicts with the APA, which states that “the reviewing court” is to “decide all relevant questions of law.” The majority went on to discuss how the court has consistently minimized the Chevron deference’s scope over time–they hadn’t even used the principle since 2016–recognition that its “justifying presumption is… a fiction.”

The dissent attempted to defend Chevron deference by stating that judges must defer to agencies with institutional knowledge because “judges are not experts in the field.” However, the majority confirms that agencies’ statutory authority is a question of law, and, therefore, deference to agencies contradicts directly with the APA.

Though the court’s decision in Loper may contradict the stare decisis principle of judicial continuity, the court found that some cases must involve the court “correcting [its] own mistakes.” Despite this, the court still confirmed that the holdings of previous cases using the Chevron deference (including Chevron itself) stand, perhaps easing concern over a wave of new litigation over old issues

No comments:

Post a Comment