Seeing a land free of antisemitism, Albert Einstein and Chinese leaders pushed plans to settle 100,000 Jews fleeing Nazis in Yunnan, the Himalayan foothills of China’s hinterland

By HARRY SAUNDERS

Today,

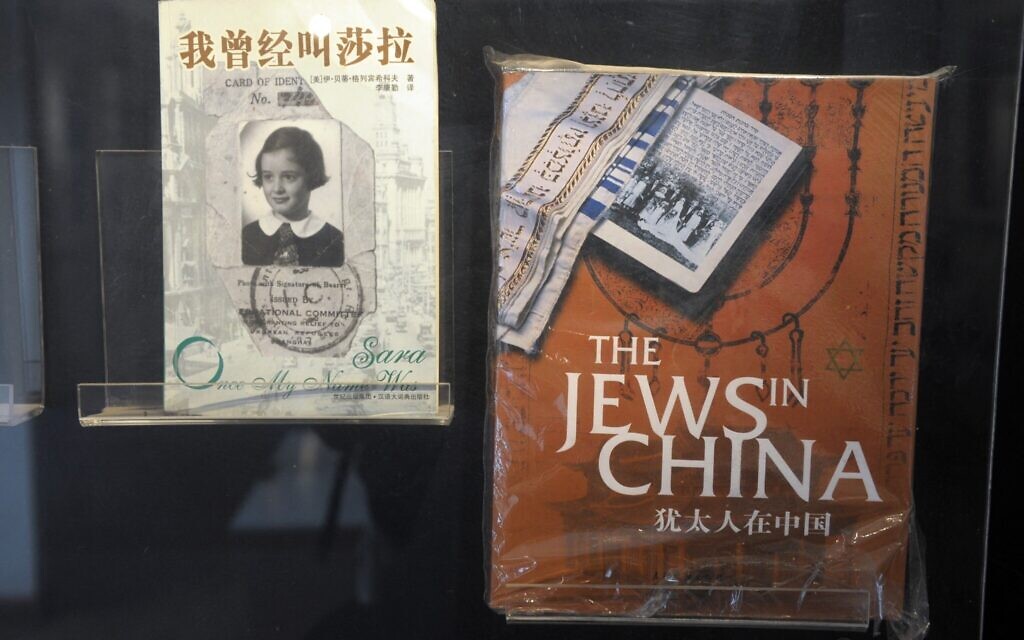

Books about Jews arriving and living in Shanghai in the late 1930s displayed at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited on May 7, 2013. (Peter Parks/AFP)

Books about Jews arriving and living in Shanghai in the late 1930s displayed at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited on May 7, 2013. (Peter Parks/AFP)

FOREIGN POLICY — On March 7, 1939, China’s top legislative official, Sun Ke, filed a dispatch to the government’s Civil Affairs Office. As a member of the Supreme Council for National Defense, he had spent the previous two years searching for ways to give China a fighting chance against the invading Japanese. Now, Sun Ke wanted to brief his colleagues on a seemingly unrelated issue: the plight of the Jewish people.

“These people suffer the most from being without a country, and for more than 2,600 years they have moved about homeless,” Sun Ke wrote, before describing Hitler’s plans for extermination. “The British want to set up a permanent settlement in Palestine,” he continued, “but this has provoked vehement opposition from the Arabs there, and the violence has not yet died down.”

Sun Ke believed that a more suitable refuge could be found in his own country. Not in Shanghai, where 20,000 Jews had already fled, but in the Himalayan foothills of China’s hinterland. With Laos to the south and what was then called Burma to the west, Yunnan was a border province with an unusually temperate climate, staggering natural beauty, and enough uncultivated land to accommodate 100,000 Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. What it lacked in scriptural significance, it made up for with its history free of antisemitic violence.

“These people suffer the most from being without a country, and for more than 2,600 years they have moved about homeless,” Sun Ke wrote, before describing Hitler’s plans for extermination. “The British want to set up a permanent settlement in Palestine,” he continued, “but this has provoked vehement opposition from the Arabs there, and the violence has not yet died down.”

Sun Ke believed that a more suitable refuge could be found in his own country. Not in Shanghai, where 20,000 Jews had already fled, but in the Himalayan foothills of China’s hinterland. With Laos to the south and what was then called Burma to the west, Yunnan was a border province with an unusually temperate climate, staggering natural beauty, and enough uncultivated land to accommodate 100,000 Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. What it lacked in scriptural significance, it made up for with its history free of antisemitic violence.

Kibbutz Nir OzKeep Watching

To Sun Ke and the unlikely coalition of Kuomintang (KMT) officials and American Jews who rallied behind his plan, Yunnan represented nothing less than the promised land of China.

In the intervening 85 years, the Yunnan settlement plan has been mostly forgotten. But never in that time has China’s position on Zionism mattered as much as it does today. Since October 7, 2023, the Israel-Hamas war has forced Beijing to reckon with its newfound status as an emerging superpower and the expectation that it will play a role in every aspect of world affairs, no matter the region.

To fully understand China’s approach to the Middle East, we must return to the 1930s, when the idea for a Jewish homeland in Yunnan transformed from the parlor room fodder of a Brooklyn dentist into the official policy of the Chinese government.

In January 1934, a dentist from Brooklyn named Maurice William wrote a letter to Albert Einstein to present his idea for Jewish resettlement in China. “During a visit at the summer home of Judge [Louis] Brandeis last September we naturally discussed the plight of German Jews,” William wrote. “He too feels that China is the one great hope for Hitler’s victims.”

Illustrative: Officials open the Jewish Memorial Park at the Fushouyuan cemetery in Shanghai, China, September 6, 2015. (Courtesy of Dong Jun/ShanghaiDaily.com via JTA)

“Your plan,” Einstein responded, “seems to me to be very hopeful and rational and its realization must be pursued energetically.” The more he thought about the plan, the more sense it made. “The Chinese and Jewish peoples,” he told William two months later, “in spite of any apparent differences in their traditions, have this in common: both possess a mentality that is the product of cultures that go back to antiquity.”

A homeland not necessarily in the Holy Land

By the time William wrote to Einstein, Jewish leaders in Europe had long been searching for a homeland outside of Palestine — “Zionism without Zion,” as historian Gur Alroey put it. Russian activist Leon Pinsker crystallized the idea in his 1882 manifesto “Autoemancipation!”, writing that “the goal of our present endeavors must be not the ‘Holy Land,’ but a land of our own.” Territorialists, as his followers came to be known, spent the next four decades trying, and failing, to achieve Pinsker’s goal.

So there was nothing revolutionary about William’s proposed settlement, except for its location. Previous plans, including the 1903 Uganda Scheme and the Zionist project itself, targeted areas within existing colonial territories. William was the first to suggest that China, a young republic still struggling to transform itself into a modern state, might be willing to make room for Jewish settlers.

William was an unlikely champion for the project. He had no pertinent formal education, no previous ties to territorialism, and had never traveled to China. But through a combination of bootstrapping self-promotion and good fortune, William became not only a well-known figure among the KMT elite but also a respected US authority on China.

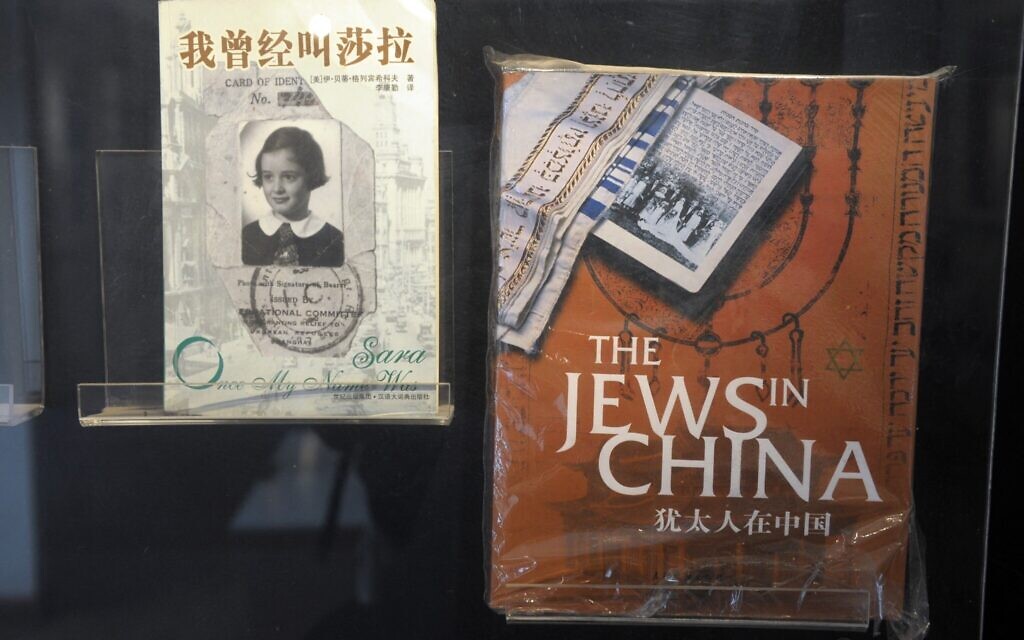

Chiang Kai-Shek, 37, standing in a formal photograph with Sun Yat-Sen, founder of the Chinese Republican government, at Wampoa Military Academy, China, in 1924. (AP Photo)

In 1923, William’s self-published refutation of Marxism, “The Social Interpretation of History,” found its way into the hands of Nationalist Party Premier Sun Yat-sen (Sun Ke’s father), who was in the process of articulating his economic vision for the country. Sun drew heavily on William’s language in a series of lectures that he delivered the following year. At one point, he mentioned the Social Interpretation by name. When the KMT published a book based on the lectures after Sun Yat-sen’s death a few years later, it catapulted William from unknown foreigner to philosophical luminary.

Americans first learned about William’s achievement from a 1927 article in Asia Magazine, which declared that Sun Yat-sen “bases his anti-Marxian position almost verbatim upon a little-known work from the pen of an American author.” William soon found himself in contact with some of the United States’ leading intellectuals, including not only Einstein and Brandeis, but also John Dewey and the Columbia historian James T. Shotwell, both of whom would later express their support for his Jewish settlement plan.

‘Abnormal influx of Jewish refugees’ in Shanghai

The Chinese government proved less receptive. Before writing to Einstein, William had discussed his plan in depth with Ambassador Alfred Sao-ke Sze, who agreed that importing German Jews could be a boon for the Chinese economy. Sze’s superiors in the KMT valued William’s opinion. But not as much as they valued their relations with Germany, which had stepped up its military and economic aid to China soon after the Nazis took power.

Constructing a settlement for the exact people that Hitler reviled was sure to offend the German government, the KMT leadership figured. Several years would pass before they became desperate enough to reconsider.

On Christmas Eve, 1938, Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC) Secretary G. Godfrey Phillips sent an urgent cable to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee: “Shanghai is gravely perturbed by [the] abnormal influx of Jewish refugees,” he warned. “Shanghai is already facing the most serious refugee problem due to Sino-Japanese hostilities. It is quite impossible to absorb any large number of foreign refugees.”

An Israeli tour guide showing Zhoushan Road, an alley in a Shanghai neighborhood that was a Jewish ghetto housing thousands of refugees during World War II, in May 2010. (AP Photo)

Shanghai enjoyed an unusual status in the early days of World War II. Japanese forces captured the city in November 1937, but they left control of the International Settlement in the hands of the SMC. Under its multinational leadership, Shanghai remained one of the few ports in the world that would allow stateless persons entry. From 1937 to 1939, more than 20,000 Jewish refugees, mostly from Central Europe, flooded into the city.

Over that same period, China suffered a string of devastating military defeats at the hands of the Japanese. After capturing Shanghai in November, the Imperial Army marched on Nanjing, forcing Chiang Kai-shek and his government to flee. By January 1939, the Japanese controlled nearly the entirety of China’s eastern seaboard. Chiang’s forces had halted the Imperial Army’s advance, but Chinese pleas for US and British military support continued to fall flat.

Soon after Phillips sent his cable, Sun Ke learned that SMC officials planned to restrict the flow of refugees to Shanghai. Resettling Jewish refugees in Yunnan suddenly seemed to him like the perfect solution to the joint crises facing his country. He began drafting his dispatch to the Civil Affairs Office the next month.

Illustrative: Jewish World War II refugees cooking in an open-air kitchen in Shanghai. (Courtesy Above the Drowning Sea/ Time & Rhythm Cinema)

The logic behind Sun Ke’s proposal was simple: If China offered refuge to the persecuted Jews of Europe, then their co-religionists in the United States and Britain might convince those governments to support China against the Japanese. “British economic support was in truth manipulated by these large merchants and bankers,” Sun Ke wrote, “and since many of these large merchants and bankers are Jewish, therefore this proposal would influence the British to have an even more favorable attitude toward us.”

In addition to their propaganda value, Sun Ke believed that Jewish refugees had something to offer a Chinese province lagging in economic development. In the short term, the symbol of Jewish refugees could help China win the war. In the long term, the refugees themselves, with their “strong financial background and many talents,” as he put it, could help China develop into a great nation.

A young Jewish refugee and her Chinese girlfriends in Shanghai during World War II (photo credit: Courtesy Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum)

His reasoning echoed that of Einstein, who told William back in 1934 that his settlement project would “place at the service of China the beneficent aid of Western skill, knowledge and science.” The historical record reveals no direct link between the plan that William presented to Einstein in 1934 and Sun Ke’s proposal in 1939. However, William’s renown in the KMT and his correspondence with Sze, the ambassador, both suggest that the similarities between his idea and Sun Ke’s proposal were the result of influence, not coincidence.

Nativist US atmosphere gives China plan death blow

Some within the Chinese government doubted that engaging with the thorny issue of Jewish refugees would be worth it. The Foreign Ministry warned that governing Jews in China would only be tenable in the short term before their demands for autonomy became too difficult to control. China’s Interior Ministry went further. “The enemy and fascist countries are constantly alleging that we are a communist state,” ministry officials wrote, “and at this time to take in a large number of Jews will make it difficult to avoid giving the enemy a pretext for propaganda. In general, in fascist theory, communism and the Jews are frequently mentioned in the same breath.”

But the promise of potentially attracting Western military assistance proved stronger. In March 1939, the KMT approved Sun Ke’s proposal and began publicizing the Yunnan plan in the Chinese and US press. That they lacked a clear plan of execution made little difference. Since the Jewish settlement’s primary appeal lay in its propaganda value, merely declaring support for it could be enough to win the sympathy of the Americans.

Visitors read a poster with information about Jewish asylum seekers in Shanghai during World War II at the Israel Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo, May 4, 2010, in Shanghai, China. (AP/Eugene Hoshiko)

When William heard about Sun Ke’s proposal, he burst into action. His peers in the United States had given him nothing but positive feedback, and with the KMT on board, it looked like his idea could finally become a reality. But the moment William started to ask for government money, things started to look different.

In response to polls revealing an electorate preoccupied with domestic issues, the Roosevelt administration’s foreign policy took a distinctly anti-immigration turn in the run-up to the 1940 presidential election. After Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938, the State Department maintained its quota of 27,730 visas for Germans, even as applications soared. By June 1939, the waiting list had grown to more than 300,000. That month, an ocean liner called the St. Louis carrying 937 mostly Jewish refugees from Hamburg got within sight of the Miami harbor. US immigration officers sent the ship back to Europe, where hundreds of its passengers were later murdered in the Holocaust.

It was against this nativist backdrop that William began holding meetings with State Department officials in August 1939. They referred him to a committee that advised Roosevelt on refugee affairs, but no records of any further meetings survive. For a project that would involve transporting 100,000 refugees from central Europe to China, the US government’s refusal to provide funding represented a death blow.

Four girls on deck of the MS St. Louis in 1939. (Courtesy of the Arlekin Players)

The exact circumstances in which the KMT abandoned the project are similarly murky. But this much is clear: In the archives of the year 1939, there was a cacophony of discussion surrounding the Yunnan settlement plans. Press conferences in Shanghai, dispatches from Chongqing, and meetings in Washington. Objections, assessments, retorts. By 1940: nothing.

In the end, it was Pearl Harbor, not the sympathy of prominent Jews, that drove the United States and Great Britain to support China. The ensuing Allied-backed counteroffensive vanquished Japan, but it left the KMT severely depleted. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seized on this weakness to relaunch its campaign to control the country. In 1949, Mao Zedong established a new government in Beijing while Sun Ke and his comrades fled to Taiwan.

They have operated in exile from Taipei ever since.

Little unites today’s CCP with the KMT of the 1930s. Chinese leader Xi Jinping will quote Marx and Lenin a million times before admitting even a nickel of intellectual debt to the KMT. But Beijing’s approach to the Israel-Hamas war, with its faith in the power of messaging, would be all too familiar to Sun Ke and his colleagues.

When Israel first launched its military operation to remove Hamas from power in Gaza and secure the return of the 251 hostages kidnapped on October 7 when thousands of Hamas-led terrorists invaded southern Israel butchering 1,200 people, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China would always support “the legitimate aspirations of the Arab and Islamic world.”

Little unites today’s CCP with the KMT of the 1930s. Chinese leader Xi Jinping will quote Marx and Lenin a million times before admitting even a nickel of intellectual debt to the KMT. But Beijing’s approach to the Israel-Hamas war, with its faith in the power of messaging, would be all too familiar to Sun Ke and his colleagues.

When Israel first launched its military operation to remove Hamas from power in Gaza and secure the return of the 251 hostages kidnapped on October 7 when thousands of Hamas-led terrorists invaded southern Israel butchering 1,200 people, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China would always support “the legitimate aspirations of the Arab and Islamic world.”

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (C) adjusts his kippa, the traditional Jewish skullcap for men, as he visits the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest prayer site, in Jerusalem’s Old City on December 20, 2013. ( Ahmad Gharabli / AFP)

After Iran launched a series of attacks against Israel in April, Wang parroted Tehran’s account, while characterizing the strikes as an act of self-defense.

Beijing’s statements have not labeled Hamas as a terrorist group, an omission that is sure to strain China’s once-blossoming trade relationship with Israel. Yet behind closed doors, Chinese diplomats keep trying to convince their Israeli counterparts that all this is just talk and should not be misconstrued as actual Chinese hostility toward Israel.

If China’s response to the Israel-Hamas war seems passive or incoherent or amateurish, it is helpful to remember how little experience Beijing has engaging with the political thicket that Zionism has always represented. Seldom in its history has China taken a position on the issue of a Jewish state. When it attempted to establish a Jewish settlement in 1939, it acted on the belief that Washington’s loyalty to the Jewish people was an unchanging and exploitable fact.

When China overestimated the influence of Jewish interests in US politics during World War II, it wasted valuable time and a few stacks of paper. But with the Chinese government now trying to position itself as the world’s alternative superpower, misreading the politics of Zionism could be far more costly.

No comments:

Post a Comment