They turned drawings into symphonies and made black boxes sing. Why were they never given their due? The maker of a new film, full of revealing archive footage, aims to put this right

Jude Rogers

@juderogers

Fri 23 Apr 2021

Wearing a black cocktail dress and a foil-bright silver headscarf, a woman stands in the corner of a drawing room performing The Swan by Saint-Saëns, while a group of men look on. Although the scene has a sedate Edwardian air to it, this is actually 1976. The woman whirls her red nails around a mysterious black box, making it sigh and lament, whisper and sing. This is Clara Rockmore, the first virtuoso of the theremin, and her audience – all there to learn – includes Robert Moog, inventor of the synthesiser.

A year later, aged 66, Rockmore would release her first album, recorded by Moog, 35 years after she made her concert debut on the instrument at New York’s City Hall, where she arranged spirituals for a black male sextet with composer Hall Johnson. Rockmore also toured widely with the bass baritone Paul Robeson in the 1940s, and turned down a request to perform on the spooky soundtrack for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 thriller Spellbound, as she wanted her instrument to be valued, not treated like a novelty.

Rockmore is one of 10 electronic music pioneers featured in Sisters With Transistors, Lisa Rovner’s debut documentary, released this weekend. Aiming to connect these women’s disparate, noisy stories, the film teems with spliced-together archive footage that recalls the mash-up style of Adam Curtis: nuclear tests and beauty competitions swirl around the many revealing clips of the musicians.

One of the first performers Rovner became captivated by was Daphne Oram, co-founder of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, who she saw in the 2003 documentary The Alchemists of Sound. Oram was a pioneer in making music from tape and developed her own compositional method, Oramics. “A quote of hers really spoke to me,” Rovner says. It came from Oram’s 1972 book, An Individual Note of Music, Sound and Electronics. “It said, ‘Do not let us fall into the trap of trying to name one man as the “inventor” of electronic music. As with most inventions, we shall find that many minds were almost simultaneously excited into visualising far-reaching possibilities.’ I wanted my film to show all those connections.”

We hear Private Dreams and Public Nightmares, Oram and fellow workshop co-founder Desmond Briscoe’s groundbreaking 1957 work, the first radiophonic composition played in full on the BBC, on the Third Programme (which became Radio 3). It was their first “attempt to convey a new kind of emotional and intellectual experience”. We then see Oram – a dead ringer for the young Margaret Thatcher – in 1963, having been awarded £3,500 (the equivalent of £62,400 today) by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Her manner is frightfully polite as she’s interviewed by a reporter, and almost apologetic. “I’ve got some little grasp of this sort of equipment,” she says, before introducing Oramics, which converts drawings into music.

There’s also a rare clip of Wendy Carlos from 1969, explaining her modular synthesiser to a French TV network, as well as 8mm footage of Pauline Oliveros that Rovner acquired from one of her old lovers. Oliveros is fascinating on screen and off. Born in 1932 and openly gay from the start of her career, she was a pioneer of the concepts of “deep listening” and “sonic awareness”. These asked the listener to spend time focusing on the depths and layers of sound, a concept Oliveros developed later in her career, recording in cathedrals and caves.

“There has to be a complete change of consciousness throughout the musical field,” said Oliveros in 1970, calling for the teaching of “music that’s written by women as well as men as well as all colours”. She added: “It will effect a great change. Listening is the basis of creativity of culture.” Although she co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center, one of the first electronic music collectives, she’s not listed as such on its Wikipedia entry. (Its male co-founders Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender get top billing.)

Oliveros wrote a piece for the New York Times in 1970 titled And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers, focusing on the difficulties of women being noticed and taken seriously in her field. It’s still online and could have been written yesterday. “Men do not have to commit sexual suicide in order to encourage their sisters in music,” is one of many compelling phrases.

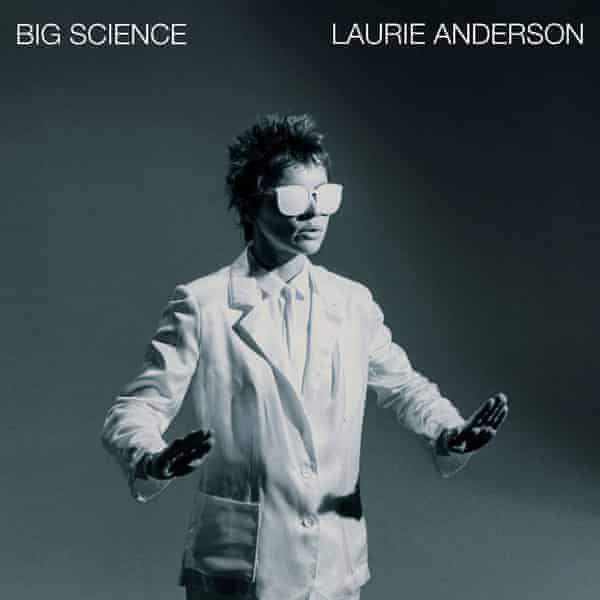

Some of them wanted to do nothing less than change the way people listenedLaurie Anderson

Rovner’s big coup for Sisters With Transistors is getting Laurie Anderson to narrate: the avant-garde composer signed up, delighted to hear that Oliveros and French composer Éliane Radigue would be properly getting their dues. Anderson’s 1981 hit O Superman used a vocoder and a polyphonic synthesiser and her delivery – knowing, icy and inviting – connects the parallel marches of technology, modernity and women’s liberty. “The spirit of modern life was a banshee,” she says, “screeching into the future.”

“It’s very interesting,” Anderson says today, “that a lot of that early work in electronics was done by women. Some of them wanted to do nothing less than change the way people listened, which is telling. They wanted to think about how sound could recalibrate our body and mind.” They also wanted to make their own machines to express themselves as music-makers and performers, as Anderson did. Her inventions include a tape-bow violin, which has magnetic tape where the bow’s horsehair should be, and a 6ft “talking stick”, a wireless instrument that can replicate any sound.

Some clips in Sisters With Transistors are more familiar, such as the much-played BBC footage of Delia Derbyshire explaining her tape machines. (A more inventive film about the composer – Caroline Catz’s Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes – premiered to acclaim at the London film festival last year, and airs next month on the BBC.) Indeed, the status of many female electronic artists has rocketed in recent decades: Oram’s name sits on a Performing Right Society prize, and her 1949 composition Still Point, written for orchestra and turntable, was performed at the 2018 Proms.

Isn’t there a risk that by saying these women are still unsung, we might be discrediting the singing that has already been done? Or that we might be fetishising them as a specialist interest? “Some people know them, but others don’t,” Rovner says bluntly. “Plus their stories quickly get forgotten again.” Suzanne Ciani, who forged a successful commercial career in electronic music from the 70s, says this explicitly in the film: “It’s two steps forward, one step back. To this day, it irks me to turn on my favourite radio station and it’s just this male parade.”

Ciani revolutionised the sound of US commercials, inventing an electronic bubbling sound for a bottle of Coke, and became the first woman to score a Hollywood film: Joel Schumacher’s 1981 comedy The Incredible Shrinking Woman. “I didn’t know it would be 14 years until another woman was hired,” she says. “We are casualties of a day-to-day system that operates without awareness that we’re even there.”

This is still an industry problem. Hildur Gudnadottír was the first woman to win a best original score Oscar for Joker, but another composer, Hannah Peel, said to me recently in the Observer: “We have to remind ourselves the number of female composers [in film] is something ridiculous. It’s gone down this year from 6% to 4%. We need to know why.”

Because of the nature of the instruments, electronic music-making is often an isolated pursuit. Nevertheless, one artist featured in Sisters With Transistors, Laurie Spiegel, tells me how struck she was by the fact that the women in the film barely knew of each other. “How different would things have been if we had?” Spiegel studied composition in London in the late 60s but heard of Oram and Derbyshire only in the past decade or so. That said, she never thought explicitly about being a female musician. “It wasn’t about me. It was about the tech, the freedoms it gave me, and the musical vistas it opened up for me to explore.”

Advertisement

Technology, says Spiegel, can be a liberator: “It blows up power structures.” The younger women who populate the film give weight to this statement – from producer Marta Salogni (Björk/the xx) who does its sound design, to such artists as Ramona Gonzalez (AKA Nite Jewel) and Holly Herndon who provide glowing voiceovers. Towards the end of the film, Herndon talks of the psychological thrill “that happens when you can see yourself in the people who are being celebrated”. As she speaks, you hear other women turning up the volume, powering up for the future.

Sisters With Transistors is released on 23 April via Modern Films. Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes is on BBC Four in May as part of the BBC’s spotlight on Coventry, UK city of culture.