‘A refugee from within America’ … Anderson in the early 80s. Photograph: Leon Morris/Getty Images

The seminal album, with its extraordinary hit single O Superman, was unlike anything the writer had ever heard. As Big Science returns, Atwood pays tribute to its prophetic dissection of 80s America

Margaret Atwood

Thu 8 Apr 2021

Here come the planes. They’re American planes! Musicologists and the less young will recognise those lines, which are from Laurie Anderson’s 1981 unlikely voice-synthesiser hit O Superman. This song, if it is one – try humming it in the shower – led to Anderson’s first multi-song album, 1982’s Big Science.

Big Science is being reissued at a very timely moment: America is reinventing itself again. It’s a self-rescue mission, and just in time: democracy, we have been led to believe, has been snatched from the jaws of autocracy, maybe. A New Deal, leading to a fairer distribution of wealth and an ultimately liveable planet, is on the way, possibly. Racism dating back centuries is being addressed, hopefully. Let’s hope these helicopters don’t crash.

I didn’t understand, back in 1981, that O Superman was about the mission to retrieve embattled Americans during the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis, in which 52 US diplomats were held by Iran for more than a year. Anderson herself has said that the song is directly related to Operation Eagle Claw, a military rescue operation that failed: a failure that included a helicopter crash. This catastrophe demonstrated that the American military-industrial Superman was not invincible, and that the automation and electronics mentioned in the song would not always win. The helicopter crash, said Anderson, was the initial inspiration for the song or performance piece. When O Superman became a hit, first in the UK and then elsewhere, Anderson claims to have been astonished. What were the chances? Very slim, you would have said ahead of time.

The seminal album, with its extraordinary hit single O Superman, was unlike anything the writer had ever heard. As Big Science returns, Atwood pays tribute to its prophetic dissection of 80s America

Margaret Atwood

Thu 8 Apr 2021

Here come the planes. They’re American planes! Musicologists and the less young will recognise those lines, which are from Laurie Anderson’s 1981 unlikely voice-synthesiser hit O Superman. This song, if it is one – try humming it in the shower – led to Anderson’s first multi-song album, 1982’s Big Science.

Big Science is being reissued at a very timely moment: America is reinventing itself again. It’s a self-rescue mission, and just in time: democracy, we have been led to believe, has been snatched from the jaws of autocracy, maybe. A New Deal, leading to a fairer distribution of wealth and an ultimately liveable planet, is on the way, possibly. Racism dating back centuries is being addressed, hopefully. Let’s hope these helicopters don’t crash.

I didn’t understand, back in 1981, that O Superman was about the mission to retrieve embattled Americans during the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis, in which 52 US diplomats were held by Iran for more than a year. Anderson herself has said that the song is directly related to Operation Eagle Claw, a military rescue operation that failed: a failure that included a helicopter crash. This catastrophe demonstrated that the American military-industrial Superman was not invincible, and that the automation and electronics mentioned in the song would not always win. The helicopter crash, said Anderson, was the initial inspiration for the song or performance piece. When O Superman became a hit, first in the UK and then elsewhere, Anderson claims to have been astonished. What were the chances? Very slim, you would have said ahead of time.

‘An eerie sound came over the airwaves’ … Atwood in the early 80s. Photograph: Wally Fong/AP

You can always remember what you were doing at certain key moments in your life. Such moments are different for everyone. Some of my moments have been attached to public tragedies: when Kennedy was assassinated, I was working at a market research company in downtown Toronto; when 9/11 struck I was in Toronto airport, thinking I was about to fly to New York. Some of my moments have been weather-related: witnessing hurricanes, caught in ice storms. And some have been musical. I was four, sitting in an armchair in Sault Ste Marie ineptly sewing my stuffed bear into its clothes, when I first heard Mairzy Doats on the radio. Blue Moon came to me sung by a live band, while I was oozing across a high-school dance floor in the clinch favoured in those days. Bob Dylan revealed himself to me in 1964, curly-headed and be-mouth-organed, on a Boston stage with barefoot Joan Baez, queen of the folkies.

Jump cut. It was 1981. Time had passed. Unsurprisingly, I was older. Surprisingly – or it would have been a surprise to me in 1964 – I now had a partner and a child, not to mention two cats and a house. Ronald Reagan had just been elected president, and the morning he was promising for America was going to be a lot different from the new age of hippiedom and feminism we’d been living through in the 70s. The religious right was on the rise as a political force. I’d already had the idea for The Handmaid’s Tale, and was struggling with whether or not I should write it. Surely it was too far-fetched?

Had I known Laurie Anderson then, she might have said: “There’s no such thing as too far-fetched.”

You can always remember what you were doing at certain key moments in your life. Such moments are different for everyone. Some of my moments have been attached to public tragedies: when Kennedy was assassinated, I was working at a market research company in downtown Toronto; when 9/11 struck I was in Toronto airport, thinking I was about to fly to New York. Some of my moments have been weather-related: witnessing hurricanes, caught in ice storms. And some have been musical. I was four, sitting in an armchair in Sault Ste Marie ineptly sewing my stuffed bear into its clothes, when I first heard Mairzy Doats on the radio. Blue Moon came to me sung by a live band, while I was oozing across a high-school dance floor in the clinch favoured in those days. Bob Dylan revealed himself to me in 1964, curly-headed and be-mouth-organed, on a Boston stage with barefoot Joan Baez, queen of the folkies.

Jump cut. It was 1981. Time had passed. Unsurprisingly, I was older. Surprisingly – or it would have been a surprise to me in 1964 – I now had a partner and a child, not to mention two cats and a house. Ronald Reagan had just been elected president, and the morning he was promising for America was going to be a lot different from the new age of hippiedom and feminism we’d been living through in the 70s. The religious right was on the rise as a political force. I’d already had the idea for The Handmaid’s Tale, and was struggling with whether or not I should write it. Surely it was too far-fetched?

Had I known Laurie Anderson then, she might have said: “There’s no such thing as too far-fetched.”

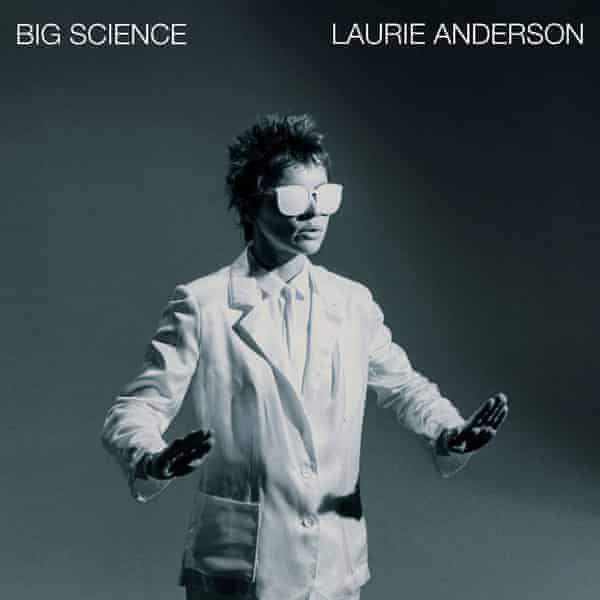

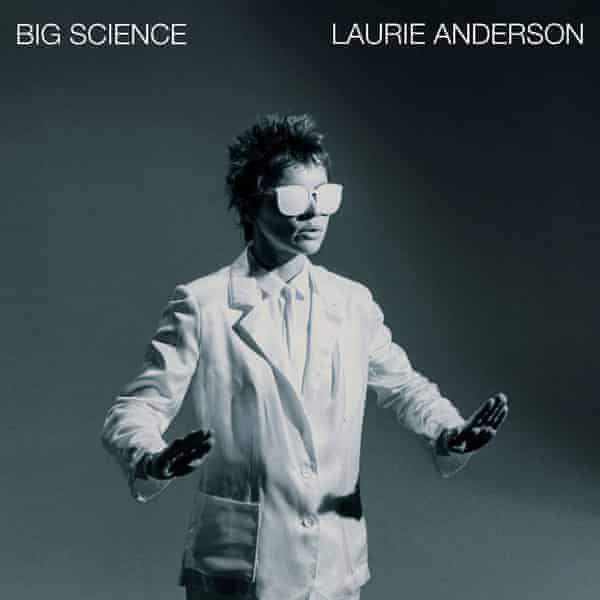

‘Like something out of a sci-fi movie’ … Anderson’s album. Photograph: Nonesuch

So, 1981. We had the radio on while cooking dinner, when an eerie sound came pulsating over the airwaves.

“What was that thing?” I said. It was not the sort of music, or even sound, that you ordinarily heard on the radio; or anywhere else, come to think of it. The closest to it was when, back in the days of record-players and vinyl, we teenagers used to play 45s on 33 speed because it sounded funny. A soprano could be reduced to a slow, zombie-like baritone growl, and often had been.

What I’d just heard, however, wasn’t funny. “This is your mother,” says a chirpy midwestern voice on an answering machine. “Are you coming home?” But it isn’t your mother. It’s “the hand, the hand that takes”. It’s a construct. It’s something out of a sci-fi movie, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers: it looks human but it’s not human, which is both creepy and sinister. Worse, it’s your only hope, Mom and Dad and God and justice and force having proved lacking.

Advertisement

“That thing” I’d been mesmerised by was O Superman. As you can see, I’ve never forgotten it. It was not like anything else, and Laurie Anderson was not like anyone else, either.

Or anyone you would ordinarily think of as a pop musician. Up until her breakout single, she’d been an avant garde performance artist and inventor, trained initially in the visual arts, and collaborating with like-minded artists such as William Burroughs and John Cage. The 70s – remembered not only for wide ties, long coats and high boots, and the ethnic look, but also for active second-wave feminism – was a period of high energy for performance art events. These were evanescent by nature, emphasising process over product. They had roots that went back to dada in the teens of the 20th century, to Group Zero, a late 50s attempt to create something new from the rubble of the second world war, and to Fluxus, active in the 60s and 70s.

So, 1981. We had the radio on while cooking dinner, when an eerie sound came pulsating over the airwaves.

“What was that thing?” I said. It was not the sort of music, or even sound, that you ordinarily heard on the radio; or anywhere else, come to think of it. The closest to it was when, back in the days of record-players and vinyl, we teenagers used to play 45s on 33 speed because it sounded funny. A soprano could be reduced to a slow, zombie-like baritone growl, and often had been.

What I’d just heard, however, wasn’t funny. “This is your mother,” says a chirpy midwestern voice on an answering machine. “Are you coming home?” But it isn’t your mother. It’s “the hand, the hand that takes”. It’s a construct. It’s something out of a sci-fi movie, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers: it looks human but it’s not human, which is both creepy and sinister. Worse, it’s your only hope, Mom and Dad and God and justice and force having proved lacking.

Advertisement

“That thing” I’d been mesmerised by was O Superman. As you can see, I’ve never forgotten it. It was not like anything else, and Laurie Anderson was not like anyone else, either.

Or anyone you would ordinarily think of as a pop musician. Up until her breakout single, she’d been an avant garde performance artist and inventor, trained initially in the visual arts, and collaborating with like-minded artists such as William Burroughs and John Cage. The 70s – remembered not only for wide ties, long coats and high boots, and the ethnic look, but also for active second-wave feminism – was a period of high energy for performance art events. These were evanescent by nature, emphasising process over product. They had roots that went back to dada in the teens of the 20th century, to Group Zero, a late 50s attempt to create something new from the rubble of the second world war, and to Fluxus, active in the 60s and 70s.

Double visions … Anderson, left, and Atwood in 2019. Photograph: Hillel Italie/AP

Anderson’s large project in Big Science was a critical and anxious examination of the US, though not exactly from without. She was born in 1947, and was thus 10 in 1957, old enough to have witnessed the surge of new material objects that had flooded American homes in that decade, 15 in 1962 during a highly active period of the civil rights movement, and 20 in 1967, when campus unrest and anti-Vietnam war protests were in full swing. The upending of norms, for a person of that age, must have seemed normal.

But although New York became her cultural base camp, Anderson was not a big-city girl. She grew up in Illinois, the heart of the heart of America. She came by her perky Mom voice and her “Howdy stranger” tropes honestly. She was a refugee, not to America but from within America: a Mom and apple pie America, an America of the past that was being rapidly transformed by material inventions, and by the freeways, malls, and drive-in banks cited in the song Big Science as landmarks on the road to town. What might be bulldozed next? How much of the natural matrix would be left? Was America’s worship of technology about to obliterate America? And, more largely, in what consisted our humanity?

Laurie Anderson: where to start in her back catalogue

As the 20th century has morphed into the 21st, as the consequences of the destruction of the natural world have become devastatingly clear, as analogue has been superseded by digital, as the possibilities for surveillance have increased a hundredfold, and as the ruthless hive mind of the Borg has been approximated through online media, Anderson’s anxious and unsettling probings have taken on an aura of the prophetic. Do you want to be a human being any more? Are you one now? What even is that? Or should you just allow yourself to be held in the long electronic petrochemical arms of your false mother?

Big Science has never been more pertinent than it is right now. Have a listen. Confront the urgent questions. Feel the chill.

A new red vinyl edition of Big Science is released on 9 April on Nonesuch.

Anderson’s large project in Big Science was a critical and anxious examination of the US, though not exactly from without. She was born in 1947, and was thus 10 in 1957, old enough to have witnessed the surge of new material objects that had flooded American homes in that decade, 15 in 1962 during a highly active period of the civil rights movement, and 20 in 1967, when campus unrest and anti-Vietnam war protests were in full swing. The upending of norms, for a person of that age, must have seemed normal.

But although New York became her cultural base camp, Anderson was not a big-city girl. She grew up in Illinois, the heart of the heart of America. She came by her perky Mom voice and her “Howdy stranger” tropes honestly. She was a refugee, not to America but from within America: a Mom and apple pie America, an America of the past that was being rapidly transformed by material inventions, and by the freeways, malls, and drive-in banks cited in the song Big Science as landmarks on the road to town. What might be bulldozed next? How much of the natural matrix would be left? Was America’s worship of technology about to obliterate America? And, more largely, in what consisted our humanity?

Laurie Anderson: where to start in her back catalogue

As the 20th century has morphed into the 21st, as the consequences of the destruction of the natural world have become devastatingly clear, as analogue has been superseded by digital, as the possibilities for surveillance have increased a hundredfold, and as the ruthless hive mind of the Borg has been approximated through online media, Anderson’s anxious and unsettling probings have taken on an aura of the prophetic. Do you want to be a human being any more? Are you one now? What even is that? Or should you just allow yourself to be held in the long electronic petrochemical arms of your false mother?

Big Science has never been more pertinent than it is right now. Have a listen. Confront the urgent questions. Feel the chill.

A new red vinyl edition of Big Science is released on 9 April on Nonesuch.

No comments:

Post a Comment