openDemocracy and LRT reveal that unproven ‘abortion reversal treatment’, supported by US Christian Right organisations, has reached Lithuania

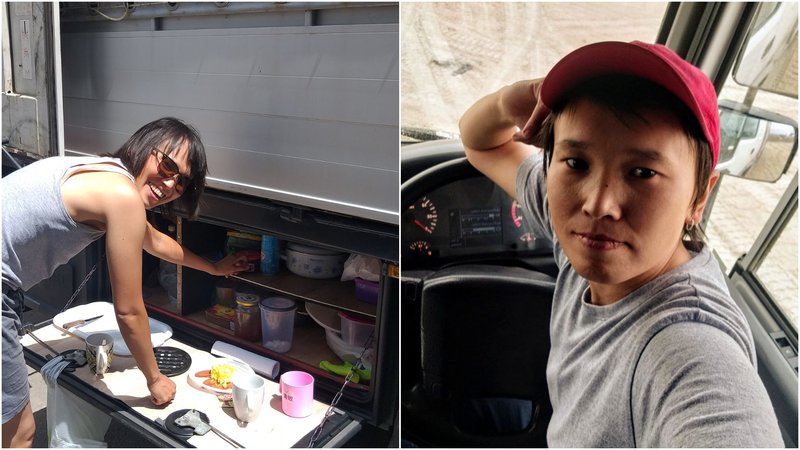

Jurga Bakaitė Tatev Hovhannisyan

15 December 2021

Illustration: Inge Snip

A doctor and NGOs in Lithuania are promoting a controversial ‘treatment’ that claims to be able to ‘reverse’ medical abortions, a joint investigation by openDemocracy and Lithuanian public broadcaster LRT can reveal.

The doctor – who was willing to prescribe medication for so-called ‘abortion pill reversal’ and who described a medical abortion as a form of “poisoning” – is linked to US Christian Right group Heartbeat International.

‘Abortion pill reversal’ (APR) is an unproven procedure that prescribes large doses of the hormone progesterone, to be taken after the first of two pills used for a medical abortion.

But the only trial into APR, in the US in 2019, was halted after some participants ended up in hospital with severe bleeding.

Earlier this year, openDemocracy’s global investigation into ‘abortion pill reversal’ revealed how the ‘treatment’ is spreading globally, including in Lithuania.

Following our investigation, health experts and lawmakers called for action from regulators to protect women from the spread of this controversial method.

‘It’s a normal thing’

Georgijus Gaidukevičius, a doctor in Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital, who offered a prescription for APR to an undercover reporter from openDemocracy, attempted to play down its risks.

“Why is this illegal?” he said. “It’s a normal thing. If a person is poisoned, one takes drugs. If one takes an abortion pill, it’s also poisoning, so we can prescribe antidotes.”

Gaidukevičius was speaking after being caught on a private messaging service, apparently willing to prescribe progesterone to ‘reverse’ a medical abortion.

“We will try to help you, but you will need to take some drugs,” he told our undercover reporter. We were given his details by a 24-hour APR hotline run out of the US by Heartbeat International.

Gaidukevičius – who is also an Orthodox priest as well as the founder of the Christian Medical Centre in Vilnius, where he works as a family doctor – claimed the “treatment” was safe, and that hormones were “not harmful”.

“Today is Sunday. I am […] not in Vilnius. Tomorrow I’ll have access to my computer at work and will write the prescription,” he told our reporter. He agreed to email it so that she could get the hormones at her local pharmacy.

Later, when confronted by LRT, he denied prescribing any hormones himself, saying he only gave openDemocracy contact details for another doctor who could do so.

Advice from the KNC ‘crisis pregnancy centre’

Abortion has been legal in Lithuania since 1955. Surgical terminations are available on request until the 12th week of pregnancy, and up to 22 weeks in some cases (for instance, if the woman’s life or health is at risk).

However, medical abortions are illegal, despite being declared safe by the World Health Organization. That’s why some Lithuanian women choose to buy abortion pills online for home use, which can lead to health risks.

Lithuania’s Free Society Institute (Laisvosios Visuomenes Institutas, LVI) is the only group offering publicly available information on APR in Lithuanian. LVI is an NGO that advocates “human dignity and life from conception to natural death” and “the natural family based on marriage and/or family ties”. It claims that “11% of crisis pregnancy centres” in the US offer the procedure, which has “saved the lives of over 1,000 babies”.

LVI often collaborates with the Krizinio Nėštumo Centras (KNC – literally ‘crisis pregnancy centre’) in Vilnius, which “seeks to prevent abortion in Lithuania”.

A journalist from LRT called the KNC hotline, claiming to be a pregnant woman who had recently taken the first pill for a medical abortion, but had changed her mind and now wanted to keep the pregnancy.

The consultant she spoke to immediately suggested she try APR, then offered a consultation with a gynaecologist. “Since progesterone is not registered in Lithuania, it is not used officially. But there is such an option abroad,” the consultant said.

After the call, the reporter received a text message from the consultant: “Do not take other pills. If you understand English, read about the ‘abortion reversal pill’. I or a doctor will call you later.”

Later, the KNC consultant told the reporter she had read online that “24 hours is a safe period” in which to try reversing an abortion. “You took the pill 12 hours ago. So, there you go, it’s not all bad. There are no guarantees, as you understand, but you can take some steps to find out,” she said.

The KNC consultant did not mention any risks involved in taking APR. She conceded that “it’s illegal in Lithuania, but women are taking it.”

‘Irresponsible’, a ‘low-probability experiment’

Progesterone is not in itself a dangerous drug. However, its use in high doses in APR has been called “dangerous to women’s health” and based on “unproven, unethical research” by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Esmeralda Kuliešytė, head of Lithuania’s Family Planning and Sexual Health Association, said that progesterone could be prescribed in rare cases to preserve a pregnancy threatened by infection or hormonal imbalance.

“But offering APR ‘treatment’ to women is irresponsible,” she told LRT. She also said that KNC is not a medical institution: “They don’t know what they are talking about. A woman should only go to a healthcare establishment and professional doctors.”

Vytautas Klimas from the Lithuanian Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists said that progesterone ‘treatment’ to reverse abortions “is not backed up by any scientific research”.

"Every such treatment is a low-probability experiment on a patient," he said.

There is pressure on us, gynaecologists, to send everyone to KNC

There have long been questions about KNC’s transparency. The centre claims to provide help to all women, including those who have had an abortion, but its website contains mainly anti-abortion content and testimonials from women who condemn abortion.

Earlier this year, the LRT documentary Colours (Spalvos) revealed that KNC had been calling women who had contacted them and pressuring them to reconsider their decisions to terminate pregnancies.

“There is pressure on us, gynaecologists, to send everyone to KNC. This was sought through the health ministry and the [Lithuanian parliament’s] health committee,” Rūta Nadišauskienė, then head of obstetrics and gynaecology at Kaunas Clinics, said in the documentary.

KNC runs high-profile ads, including on TV, and is frequently in the limelight because of its connections to powerful people.

It is supported by several celebrities including TV host Rolandas Mackevicius. In October 2020, Diana Nausėdienė, wife of the Lithuanian president Gitanas Nausėda, hosted an event for KNC, LVI and a number of other NGOs at the presidential palace. Human rights organisations criticised the event for “politicising abortions”.

Last month, LVI organised another conference (this time online) with the first lady and an MP attending, funded by the labour ministry.

Progesterone not approved for use in pregnancy

Asked about offering unproven progesterone treatment, KNC told us, in a written response, that it simply provided information on “the APR method used in global practice”.

“There are women who buy [abortion] pills illegally and change their minds after taking them. In this case, the progesterone pill is used in some countries,” KNC said.

“We believe that a woman has the right to be informed about the various options and to make the most appropriate decision while consulting with her doctor.”

The Lithuanian health regulator allows for the prescription of drugs outside of their intended purpose only in exceptional cases. The decision must be taken by a panel of doctors and requires the patient’s written consent. Even then, the dosage and the course of treatment must be based on scientific evidence.

The regulator confirmed to LRT that progesterone is not included in the country’s register of medicinal products for use in pregnancy. It is prescribed to treat premenstrual syndrome, irregular periods and premenopausal or menopausal symptoms.

“To the health ministry’s knowledge, there are no clinical trials confirming that progesterone could help preserve pregnancy after the intake of drugs intended to terminate the pregnancy,” the ministry said.