A Soviet-era law banning women from more than 200 jobs has finally been overturned in Kazakhstan. But the fight for gender parity is not over

Aigerim Kamidola

13 December 202

Kazakhstan's list of banned professions originally stemmed from 1930 Soviet legislation

Illustration: Lena Nemik. Used with permission

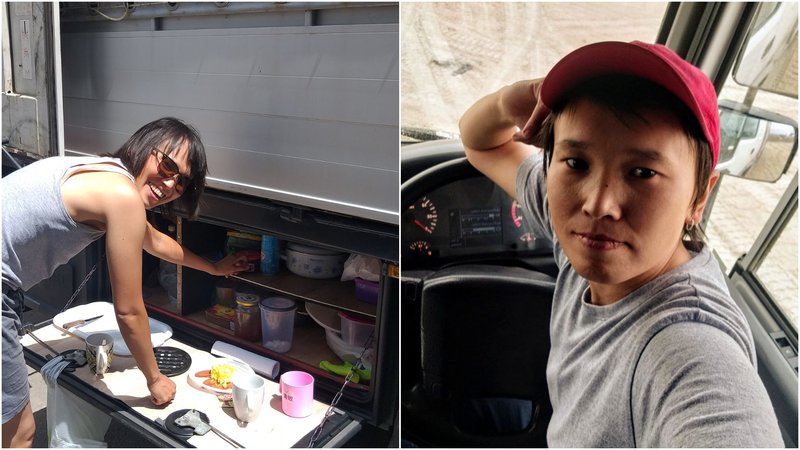

In 2019, Almagul Kabylbekova found work as a heavy goods vehicle driver in Temirtau, an industrial town in central Kazakhstan. But this job didn’t last for long, because women were not allowed to be lorry drivers. Or railway wagon inspectors, or crane operators.

Under a Soviet-era provision carried over into Kazakhstani law, these and more than 200 other occupations were designated “banned jobs for women” – until a series of amendments to the country’s labour code lifted the ban in October.

Two years ago, Kabylbekova didn’t know that her employment was prohibited. Then, when she posted a motivational video on YouTube about her work routine, her employer asked her to remove it immediately and dismissed her. It was then that she discovered that her job had been listed as a “light vehicle driver”, because she was officially banned from working her actual job, as a heavy vehicle driver. So after four months, Kabylbekova was on the job market again, accepting work here and there until she found another lorry driver job abroad, where it was legal.

When COVID-19 hit and borders were sealed, Kabylbekova had to return to Kazakhstan. She then discovered that she could not apply for unemployment benefits for a job that she was not allowed to perform in the country.

With little other recourse, Kabylbekova decided to join the battle that advocates had been fighting for years to abolish the ban.

Almagul Kabylbekova | Source: Personal archive

This job is not for women

The ban was originally established in the 1930s, when Soviet legislators argued that to “ensure the protection of maternity and women’s reproductive health”, women should be banned from hundreds of jobs. At its height in 1978, the ban consisted of 431 prohibited occupations. As of this year, 229 occupations were included in the ban.

The ban was translated into the labour codes of independent Kazakhstan – as well as that of other new states – after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, there are still 446 banned jobs for women in Russia, 456 in Kyrgyzstan, 326 in Tajikistan, and 182 in Belarus. Only in Ukraine has the ban been fully lifted, ending in 2017.

In Kazakhstan, the list of banned jobs was occasionally revised with minor changes, usually ahead of a United Nations external review. In 2019, the UN Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) recommended that the Kazakhstani government repeal the list within two years. The deadline for the country’s report on its compliance with the recommendations was coming up in November, with CEDAW due to revise the process of the legislation in 2022.

Just in time for the CEDAW review, on 12 October 2021, Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed amendments repealing the ban.

Reproductive rights and work

If it were not for the relentless advocacy by women in Kazakhstan, this blanket ban on women’s employment – based on the government’s ‘care’ for ‘safeguarding’ women’s reproductive functions – could have remained legal for another 90 years with sporadic reviews.

When I started working on the repeal of the ban in 2018, there was little public awareness about the existence of the ban and the list of prohibited occupations for women in Kazakhstan.

This job is not for women

The ban was originally established in the 1930s, when Soviet legislators argued that to “ensure the protection of maternity and women’s reproductive health”, women should be banned from hundreds of jobs. At its height in 1978, the ban consisted of 431 prohibited occupations. As of this year, 229 occupations were included in the ban.

The ban was translated into the labour codes of independent Kazakhstan – as well as that of other new states – after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, there are still 446 banned jobs for women in Russia, 456 in Kyrgyzstan, 326 in Tajikistan, and 182 in Belarus. Only in Ukraine has the ban been fully lifted, ending in 2017.

In Kazakhstan, the list of banned jobs was occasionally revised with minor changes, usually ahead of a United Nations external review. In 2019, the UN Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) recommended that the Kazakhstani government repeal the list within two years. The deadline for the country’s report on its compliance with the recommendations was coming up in November, with CEDAW due to revise the process of the legislation in 2022.

Just in time for the CEDAW review, on 12 October 2021, Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed amendments repealing the ban.

Reproductive rights and work

If it were not for the relentless advocacy by women in Kazakhstan, this blanket ban on women’s employment – based on the government’s ‘care’ for ‘safeguarding’ women’s reproductive functions – could have remained legal for another 90 years with sporadic reviews.

When I started working on the repeal of the ban in 2018, there was little public awareness about the existence of the ban and the list of prohibited occupations for women in Kazakhstan.

The author at the 74th UN CEDAW meeting, 2019 | Source: Personal archive

with a few exceptions, bringing the topic of banned jobs for women to the table was often met with surprise and disbelief among civil society advocates, women’s rights groups, and state authorities alike. Until recent years, this was a forgotten issue.

Yet, women had been working at banned jobs for years in Kazakhstan. Underground.

Indeed, women who trained and excelled at banned jobs were forced to operate in the informal grey zone: they had to settle for significantly lesser pay, with no social security benefits and labour protections, and were often left at the mercy of their employers and vulnerable to abuse.

After international pressure from CEDAW, the Human Rights Council, other UN bodies, the International Labour Organization, and the World Bank, the issue of banned jobs for women made it into the ruling party Nur Otan’s election programme at the end of 2020.

By May 2021, the infamous list was being discussed in Parliament, which ultimately decided to scrap the ban altogether.

with a few exceptions, bringing the topic of banned jobs for women to the table was often met with surprise and disbelief among civil society advocates, women’s rights groups, and state authorities alike. Until recent years, this was a forgotten issue.

Yet, women had been working at banned jobs for years in Kazakhstan. Underground.

Indeed, women who trained and excelled at banned jobs were forced to operate in the informal grey zone: they had to settle for significantly lesser pay, with no social security benefits and labour protections, and were often left at the mercy of their employers and vulnerable to abuse.

After international pressure from CEDAW, the Human Rights Council, other UN bodies, the International Labour Organization, and the World Bank, the issue of banned jobs for women made it into the ruling party Nur Otan’s election programme at the end of 2020.

By May 2021, the infamous list was being discussed in Parliament, which ultimately decided to scrap the ban altogether.

Celebrate with caution

That the long-standing ban is now a matter of the past is definitely worth celebrating.

Lifting the blanket ban without reservations over ‘women’s reproductive function’ is a win against the framing of women exclusively as mothers and caregivers in Kazakhstan. It is an important milestone in challenging discrimination and gender stereotypes and has a potential for a trickle-down effect in the wider Central Asian region, where similar bans still exist. The grassroots mobilisation of women proved to be effective.

Yet, the extent of this success should be taken with a pinch of salt. The amendments that scrapped the list are not a recognition of decades-long discrimination in the country, or of women’s agency. Instead, the changes were included in an umbrella law emphasising the need for social protection (‘On Issues of Social Protection of Certain Categories of Citizens’), alongside provisions on social benefits for people and children with disabilities, their caregivers and families. Once again, women are regarded as objects of socio-economic measures.

Kazakhstani MP Zarina Kamasova, a member of the country’s parliamentary committee on social and cultural development, told openDemocracy that the amendments were pushed “onto the last train” – meaning they were included as the last item in a draft law at the end of the parliamentary year.

Ultimately, lifting the ban is largely a move to please Kazakhstan’s international partners. It was hastily passed because the government wanted to whitewash its failure to adopt a draft law on domestic violence

The ruling party presented the lifting of the ban as a favour from the top, to which everyone should rejoice, not as inalienable rights won by women after a long struggle of workers and advocates. During my meetings with MPs as the amendments were being discussed in Parliament, I was asked to avoid referring to ‘feminism’ in my arguments, because this kind of political association could have stirred public outcry.

Ultimately, lifting the ban is largely a move to please Kazakhstan’s international partners. It was hastily passed because the government wanted to whitewash its failure to adopt a draft law on domestic violence, which was shelved for revisions in January 2021 after yielding to demands of conservative groups.

Next year, the CEDAW review will assess Kazakhstan’s progress on four issues: the adoption of a law on domestic violence, the abolition of a mandatory pre-requisite of gender-reassignment surgery before a person can change their gender in official documents or ID, the criminalisation of forced sterilisation of women and abortion, and the repeal of the list of prohibited occupations for women. With the first three in a stalemate, lifting the ban on employment of women was ‘the lowest hanging fruit’. In essence, lifting the ban was deemed less dangerous and an easy way for the government to compensate for failures elsewhere.

Lia Nadaraia, a member of the CEDAW Committee, and its former Country Rapporteur on Kazakhstan, noted that “even the repeal of the ban and the list of prohibited occupations for women would not brighten Kazakhstan’s overall dismal record and would not help it to ‘score’ well at the review”.

A job not done

This year, Kazakhstan marked its 30th anniversary of independence from the Soviet Union. And while the repeal of the ban could have been a welcome celebration of this event, the Kazakhstani government’s continuing failure to pass domestic violence legislation and protect transgender people’s rights sadly puts the country it in line with the global trend of anti-gender backlash.

What’s more, women are still not being treated as equals at work. “I am happy that [the ban] has been revoked, but this has not affected my career and pay in any way,” Almagul Kabylbekova told me. She has found employers are still reluctant to hire women, while male colleagues remain hostile to women in formerly banned jobs.

Scrapping the ban is, arguably, only half the job. Kazakhstan must not, as the CEDAW further recommends, “facilitate access for women” to the occupations in question. The Kazakhstani’s state obligation does not end by deleting a paragraph in the labour code – as much as its government would like it to. Eliminating women’s remaining barriers to work are “even more urgent today”, says Tea Trumbic, manager of the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law programme, in light of how the COVID-19 pandemic has “widened long standing gender inequalities around the world”.

Now, it is the task of the Kazakhstani government to properly inform women, employers and wider society that the ban has been abolished – and move the country away from outdated gender stereotypes. It is time that women are guaranteed equal access to professional education and employment at formerly prohibited occupations.

Update 13 December: standfirst image replaced with illustration by Lena Nemik.

No comments:

Post a Comment