The making of “Ram Ke Naam”

In 1984 after her Sikh bodyguards assassinated Indira Gandhi, a revenge pogrom took the lives of over 3000 Sikhs on the streets of Delhi. Many killer mobs were led by Congress Party members, but some were led by the RSS and BJP as well. This is a fact forgotten by history but recorded in newspaper headlines of the day. It was this massacre that set me on the to road to fight Communalism with my camera. For the next decade I recorded different examples of the rise of the religious right, as seen in diverse movements from the Khalistani upsurge in Punjab to the glorification of Sati in Rajasthan and the movement to replace the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya with a temple to Lord Ram.

The material I filmed was very complex and if I had tried to encompass it all into a single film, it would have been too long and confusing. Eventually three distinct films emerged from the footage shot between 1984 and 1994, all broadly describing the rise of religious fundamentalism and the resistance offered by secular forces in the country. “Una Mitran Di Yaad Pyaari/ In Memory of Friends”, the first film to get completed, spoke of the situation in the Punjab of the 1980’s where Khalistanis as well as the Indian government were claiming Bhagat Singh as their hero, but only people from the Left remembered the Bhagat Singh who from his death cell wrote the booklet, “Why I am an Atheist”.

The second film was “Ram Ke Naam/In the Name of God” on the rise of Hindu fundamentalism as witnessed in the temple-mosque controversy in Ayodhya. The third was “Pitra, Putra aur Dharmayuddha/Father, Son and Holy War” on the connection between religious violence and the male psyche. All three films tackled Communalism, but each used a different prism to analyse what was happening. “In Memory of Friends” highlighted the writings of Bhagat Singh suggesting that class solidarity was the antidote to religious division. “Father, Son and Holy War” looked at the issue from the prism of gender.

For this article, I will concentrate on “Ram Ke Naam”, the middle film of what became a trilogy on Communalism. While the film covers a two year span from 1990 onwards, the back story begins in the mid-1980’s when the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and sister organizations of the Hindutva family (the Sangh Parivar) was searching for a way to capture the imagination of the Hindus of India who at 83%, constitute the real vote bank of this country. A Dharam Sansad (Parliament of Priests) in 1984 (the year Indira Gandhi was killed and the Congress rode to power on a sympathy wave) identified 3000 sites of potential conflict between Hindus and Muslims that could mobilize the sentiments of Hindus and polarize the nation. The top three sites chosen were at Ayodhya, Kashi and Mathura. The Dharam Sansad decided to start with the Ram temple/Babri Mosque in Ayodhya. Soon a nationwide village to village campaign to collects bricks and money to build a grand Ram temple in place of the Babri mosque began. The campaign went international as NRI’s chipped in from distant lands. By design or by remarkable coincidence, India’s state controlled TV channel, Doordarshan started to run a never-ending serial on the Hindu epic – The Ramayana (The story of Lord Ram). In those days there were few other TV channels and the whole nation was hooked onto mythology. These were the ingredients already at play when BJP stalwart L. K. Advani set out on his chariot of fire.

“Ram Ke Naam” follows the Rath Yatra of L.K. Advani who in 1990 traversed the Indian countryside in an air-conditioned Toyota dressed up by a Bollywood set-designer to look like a mythological war chariot. The stated objective was to gather Hindu volunteers, or “kar sevaks” to demolish a 16th century mosque built by the Mughal emperor Babar in Ayodhya and build a temple to Lord Ram in its exact location. The rationale for this act of destruction and construction was that Babar had supposedly built this mosque after demolishing a temple to Lord Ram that had marked the exact location of Lord Ram’s birth. This was justified as an act of historic redress for the many wrongs inflicted by Muslim invaders and rulers on their native Hindu subjects, a theme that runs through all Hindutva discourse like a flaming torch.

I started the film instinctively, shooting the Rath Yatra when it arrived in Bombay in 1990 and then following it through various segments of its journey. At many places the Rath passed through, it left a trail of blood as kar sevaks attacked local Muslims either for not showing due respect or just to display their might. By the end of its journey over 60 people had been killed and many more injured in the wake of the Rath.

Most of our shoot was done with a two-person crew consisting of myself with an old 16 mm camera and colleagues who accompanied me on different legs of the shoot. For the leg that eventually reached Ayodhya, Pervez Merwanji recorded sound on our portable Nagra. Pervez was a dear friend and a filmmaker in his own right, having just made his brilliant debut feature “Percy” which went on to win a major award at the Mannhein International Film Festival. Despite this he was not too proud to don the mantle of sound recordist on an unheralded independent documentary project like ours. It turned out to be the last film he would ever work on. Pervez contracted jaundice, probably during our shoot, seemed to recover, but then his liver failed him and he passed away never having seen the final edit of our film.

Our actual filming was staggered over a year and a half, and we were able to research as well as shoot in this period. We learned that contrary to the theory that votaries of Hindutva were propagating that claimed that there was a temple underneath the mosque, the artefacts that archaeologists had originally found in digs in the vicinity had nothing to do with any temple. According to historians, in the 7th century at the location of present day Ayodhya, probably stood the Buddhist city of Saket. We learned that the proliferation of Akhadas (military wings attached to temples) in Ayodhya had nothing to do with the long war to liberate the birthplace of Lord Ram as was being claimed by Hindutva ideologues, but owed their origin to the ongoing rivalry between armed Shaivite and Vaishnavite sects in the middle ages. Most importantly we learned that in the 16th century, the poet Tulsidas visited Ayodhya many times as he composed his famous Ram Charitra Manas, a text which converted the relatively obscure Sanskrit Ramayana into khadi boli, a form of Hindi, that popularized the story of Lord Ram for the ordinary folk of North India. Not only does Tulsidas never mention that a temple marking the birthplace of Lord Ram was just demolished by Babar, there is another telling fact. Until the 16th century the Rama legend was largely restricted to the few Brahmins who knew Sanskrit. It is only after Tulsidas’s Hindi version had spread that Ram became a popular god for the masses and Ram temples sprouted across the country. In other words in the middle of the 16th century when the Babri Mosque was built, it is highly unlikely that there were any Ram temples at all. Today Ayodhya is full of Ram temples and at least twenty of them claim to be built at the birthplace of Ram. The reason is obvious. Any temple that establishes itself as the birthplace of Ram gets huge donations from its devotees.

Some of this research is hinted at in the finished film but rarely made explicit as I felt that it would be more powerful for our film to rely on the logic of events unfolding before the camera in 1990-91 rather than become a theoretical and didactic treatise. Ideally I, or someone else should have made an accompanying booklet to point out the many footnotes and annotations that such a film really needs.

30th October 1990 had been declared by L.K. Advani as the target date for “Kar Seva” at the disputed Ram Janmabhoomi/Babri Mosque site in Ayodhya. Pervez and I headed to Uttar Pradesh. We were trying to catch up with the Rath at some of its scheduled stops. The trains were already jam full. We squeezed into a Third Class compartment where we could barely sit on top of our luggage. We had got on a wrong train and it was impossible to get out! It turned out to be a stroke of luck as the train took us to Patna, Bihar where the Left front along with Bihar Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav were holding a huge anti-Rath rally at the Gandhi Maidan. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7XRvjYQOaI)

A.B. Bardhan of the CPI made a brilliant appeal to preserve India’s syncretic culture and Lalu Prasad Yadav gave a stern warning telling Advani to turn back from the brink. A few days later he kept his promise. Advani was arrested and the Rath Yatra finally came to a halt in Bihar. Not so the kar sevaks who used all modes of transport to continue to head towards Ayodhya.

We caught a train back to Lucknow. There we spent almost 10 days trying to get permission to enter Ayodhya. Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav had vowed to protect the Babri Mosque and claimed that he had turned Ayodhya into an impenetrable fortress where not just kar sevaks but “parinda par na kar payega” (not a bird could fly cross). As it turned out in the end the only people who had difficulty getting into Ayodhya were journalists and documentarians like us.

We finally reached Ayodhya on the 28th of October, two days before the planned assault on the mosque. Here we met Shastriji, an old Mahant (temple priest) who in 1949 had been part of the group that had broken into the Babri Mosque at night and installed a Ram idol in the sanctum sanctorum. From that day on, the site had become disputed territory as District Magistarate K.K. Nair refused to have the idols removed. As “Ram Ke Naam” points out, K.K. Nair after retiring from government service went on to join the Jan Sangh Party (precursor of the BJP) and became a Member of Parliament.

Shastriji, the Mahant, was proud of installing the idols and a little miffed that everyone had forgotten his role. Hindutva videos, audios and literature had proclaimed that what happened in 1949 was a “miracle” where the god Lord Ram appeared at his birthplace. Shastri was arrested and released on bail by the District Magistrate, K.K.Nair. Till the day we met him 41 years later, he had remained free.

We went across the Saryu bridge to Ayodhya’s twin city, Faizabad. Here we met the old Imam of the Babri Mosque and his carpenter son who recounted the 1949 story from their perspective. The District Magistrate had told them after the break-in that order would soon be restored, and that by next Friday they could re-enter their mosque for prayers. As the Imam’s son put it “We are still waiting for that Friday”.

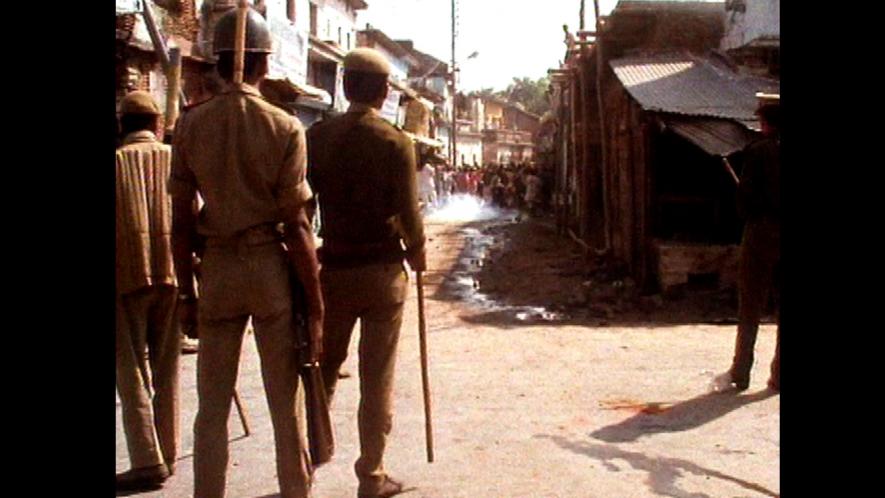

As 30th October dawned and we made our way on foot to the Saryu bridge at Ayodhya, we could see that CM Mulayam Singh’s promise that no one would get through to Ayodhya was proving false. Already several thousands had gathered by the bridge, despite the curfew. There had been a small lathi charge while shoes and footwear were scattered all over the bridge. Busloads of arrested karsevaks were being driven away after arrest. What we did not notice at the time was that many of these buses would stop at a short distance and the kar sevaks would disembark to rejoin the fray. By the side of the bridge thousands were chanting at the police “Hindu, hindu bhai bhai, beech mein vardi kahan se aayee? (All Hindus are brothers. why let a uniform get between us?)”.

As the day progressed it was heartbreaking to those of us who knew that any attack on the mosque would rent apart the delicate communal fabric of the nation.. We had believed Mulayam Singh’s strong rhetoric that he would stop karsevaks long before they reached the mosque. What we saw on the ground was bewildering. Not only were thousands pouring in despite the curfew but at many places there was active connivance from the police and paramilitary forces. There was utter confusion. In the end some karsevaks did break through to attack the mosque but at the very last instance, the police opened fire. Some karsevaks reached the top of the mosque’s dome and tied their orange Hindutva flag. Others broke into the sanctum sanctorum where the idols were kept but police firing prevented the larger crowd from demolishing the mosque. In all 29 people, young and old, lost their lives. Later BJP and VHP propaganda claimed that over a thousand had been killed and thrown into the Saryu river. The think-tank of Hindutva then initiated another Rath Yatra across the country carrying the ashes of their Ayodhya “martyrs”.

On the night of the 30th, in the sombre mood that the attack had spawned, we met Pujari Laldas, the court-appointed head priest of the disputed Ram Janmabhoomi/Babri Mosque site. Laldas was an outspoken critic of Hindutva despite being a Hindu priest and had received death threats. The UP government had provided him with two bodyguards. It is this wonderful interview of one of independent India’s unsung heroes that gives “Ram Ke Naam” its real poignancy. Laldas spoke out against the VHP pointing out that they had never even prayed at the site but were using it for political and financial gain. He spoke of the syncretic past of Ayodhya and expressed anguish that Hindu-Muslim unity in the country was being sacrificed by people who were cynically using religion. He predicted a storm of mayhem that would follow but expressed confidence that

this storm too would pass and sanity would return.

For “In Memory of Friends”, I had used a prism of class as seen through the writings of Bhagat Singh to speak of the Punjab of today. In reality, by the late 1980’s classical Marxist analysis and class solidarity were no longer exclusively effective tools in an India and a world where the ideas of the Left were losing out to consumer capitalism. The Soviet Union was collapsing and China was embracing state capitalism. The USA was the only super power left in the world, which itself was fragmenting into its religious and ethnic sub-parts. Yugoslavia disintegrated into internecine warfare. The USA with its ally, Saudi Arabia, stoked Islamic fundamentalism in Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight Communism which in turn helped Kashmiri militants take up the gun. In Punjab, Sikh militants were rising and in Northern India, Hindu militants came into their own. For “Ram Ke Naam” the sane voice of the Hindu priest Pujari Laldas played the role that Bhagat Singh’s writings had done in my previous film. The Left antidote to Communalism was still present through the Patna speech of CPI’s AB Bardhan. But it was now joined by a liberation theologist in the form of Pujari Laldas. The violent reaction of upper caste Hindus to the attempt by Prime Minister V.P. Singh to implement a Mandal Commision report granting reservations to ‘backward’ castes, had led to upper caste Hindus embracing Hindutva and the Mandir (Ram temple) movement. This had not yet trickled down the Caste order. Wherever we went in UP, Dalits and “Backward Castes” spoke out against the Ram temple movement. This became the third spoke in the anti-Communal wheel.

The film was complete by late 1991. We had some hiccoughs and delays from the censors but finally cleared this hurdle without cuts. The film went on to win a national award for Best Investigative Documentary as well as a Filmfare Award for Best documentary. At the 1992 Bombay International Documentary Film Festival, Jaya Bacchan was head of the jury. “Ram Ke Naam” did not get a mention. Several critics commented that the film was raking up a dead issue as the Babri Mosque was intact and the film would unnecessarily give the country a bad name abroad. Later that month I attended the Berlin Film Festival with “Ram Ke Naam”. I learned to my horror that Amitabh and Jaya Bacchan, who were also guests at this festival, had told the Festival authorities that should not have selected such an “anti-India” film.

On the strength of our national award I submitted it for telecast on Doordarshan. Any government that actually believed in a secular India, would have shown such a film many times over so that our public could realize how religious hatred is manufactured for narrow political and financial gains. Widespread exposure may have undermined the movement to demolish the mosque. The BJP was not yet in power. Yet Doordarshan refused to telecast the film and I took them to court. 5 years later we won our case and the film was telecast, but the damage had long been done.

After the October 30 attack in 1990 and the death of 29 karsevaks, the BJP, which had been in coalition with VP Singh’s Janata Dal Party government at the centre, pulled out its support. Chandra Shekhar briefly came to power at the centre but quickly lost to Narsimha Rao’s Congress in the wake of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination. In UP Mulayam Singh’s government gave way to a BJP government. One of its first steps was to have Pujari Laldas removed as head priest of the Ram Janmaboomi/Babri Masjid, and then to remove his bodyguards. Conditions were now ripe for the major assault.

On December 6, 1992 with the BJP in power in UP, and a strangely acquiescent Narsimha Rao led Congress government at the centre, the Hindutva brigade finally succeeded in demolishing the Babri Mosque. Pujari Laldas’s predictions of large scale violence in the region came true. The old Imam and his son from Faizabad I had interviewed were put to death on 7th December 1992. While Muslims were slaughtered across India, in neighbouring Pakistan and Bangladesh, the Hindu minority was targeted and temples destroyed. In March 1993, bomb blasts in Mumbai organized by Muslim members of the mafia killed over 300 people. The chain reaction set into motion since those days has still to abate.

Back in 1991 our première had been held in Lucknow, capital of UP. Pujari Laldas came for the screening and asked for several cassettes of the film. When I asked about his own safety, he laughed and said he was happy that now his views would circulate more widely. As he put it, if he had been afraid, he would not have spoken out in the first place.

A year later, a tiny item on the inside pages of the Times of India noted-“Controversial priest found murdered.” Pujari Laldas had been killed with a country-made revolver. The newspaper article never told us that the real “controversy” was the fact that this brave priest believed in a Hinduism that is the mirror opposite of Hindutva.