Violence in Healthcare: Profit over Care

Image by Alexander Mills.

Following the murder of United Healthcare’s CEO, social media has been flooded with outrage, mostly directed against insurance companies that deny care.

On social media, I have seen reports from people I know. They express, as I do, that murder is not the answer, but they go into detail about the pain caused by the denial of their insurance claims, often due to insurance use of AI to evaluate the “need.”

Our capacity for empathy is what makes us human. I see this in my friends as they grapple with the ethical crisis: “It was wrong to shoot him, but…” One friend says it has shed light on a real problem; another says, “They don’t need him for their investors’ meeting—nothing changes.”

I surprise my friends; they know I have complained about healthcare insurance for more than a decade. They know I question whether or not a better system could have saved my brother’s life when he died at 33, but this time I give a different response.

In an early episode of the Twilight Zone (Button, Button) there is a kind of thought experiment: would an ordinary person be willing to kill a total stranger for a large sum of money? To accomplish the task all one need to do is push the button, someone they don’t know will die, and they will receive payment.

Now, my friends accuse me of being too abstract. “What does healthcare have to do with The Twilight Zone?” they ask. But isn’t that exactly what AI represents?

AI is just the substitute for the Twilight Zone button. The AI is a program that denies claims and prevents people from receiving life affirming care. The casings of the bullets that killed the CEO bore the words “deny,” “defend,” “depose.” Of course that is murder, but is it any less violent when a person dies due to lack of access or treatment? The people making profits clearly are disconnected from the people that die when their insurance doesn’t cover needed treatment or testing.

In classrooms I talk about violence regularly. Most of the time people think of direct violence like physical assaults, murder, or war when the subject comes up. But there are also forms of indirect violence that can be cultural, structural or systemic. One of the most common I discuss is about access.

Paul Farmer, a medical doctor dedicated to providing medical services to those who cannot afford care, provides a fantastic description dealing with medical treatment:

“The term ‘structural violence’ is one way of describing social arrangements that put individuals and populations in harm’s way […] The arrangements are structural because they are embedded in the political and economic organization of our social world; they are violent because they cause injury to people (typically, not those responsible for perpetuating such inequalities). With few exceptions, clinicians are not trained to understand such social forces, nor are we trained to alter them. Yet it has long been clear that many medical and public health interventions will fail if we are unable to understand the social determinants of disease.”

The definition comes in response to the observation:

“Because of contact with patients, physicians readily appreciate that large-scale social forces—racism, gender inequality, poverty, political violence and war, and sometimes the very policies that address them—often determine who falls ill and who has access to care. For practitioners of public health, the social determinants of disease are even harder to disregard.”

I do have concern for medical personnel. They are working hard yet are receiving lots of the person-to-person blame for disappointing outcomes in treatment. Going through the testimonies of people who have watched loved ones anguishing in pain or dying makes the rage understandable.

Insurance companies have apparently outsourced life and death medical decisions to AI, and they may even blame it on a fiduciary responsibility to maximize profit for shareholders. Insurance companies dictate so much of our treatment pathways that it’s easy to forget their primary existence is not to improve patients’ quality of life but to generate profit.

Doctors take an oath: ‘First, do no harm.’ Insurance companies, however, have no such obligation. Increasingly, the public is paying the price, and I really hope that we can change the narrative from revenge and bloodlust in perceived reaction to what these companies are doing to one of change that starts producing quality healthcare from everyone. With people power we can make this needed change.

Health Insurance Killing: Economics Does Have Something to Say

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

I’m not one to generally tout the wisdom of the economics discipline, but it actually does offer some useful insights into the likely motive for the murder of Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare (UHC). According to media accounts, the suspect, Luigi Mangione, was angered by his own and others’ experiences being turned down when submitting claims for healthcare service. United and other insurers make a profit by restricting the claims they pay, so their profit motive goes directly against people’s need to get healthcare.

That simple story is undeniably true, but the picture is more complicated. Many of the claims being submitted are outlandishly high, due to high prices for drugs and medical equipment, as well high fees for medical specialists and hospital administrators. In recent years, private equity firms have also seen the healthcare industry as a promising source of profits.

Our doctors on average get paid more than twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. Our pay structure for CEOs and other top corporate executives is out of whack and badly needs reforming. Private equity is largely a predatory industry that often profits by conducting itself in ways that would be too embarrassing for a publicly traded company.

These are all important sources of bloat in the healthcare sector, as is the insurance industry itself, but I want to focus on the relatively simple story of prices for drugs and medical equipment. This is where one of the most basic principles of economics, marginal cost pricing, has much to tell us.

When we see drugs that sell for tens of thousands of dollars — or even hundreds of thousands — for a course of treatment, it is almost never because the drug is expensive to manufacture and distribute. It is due to the fact that the government has granted the drug company a patent monopoly for its drug. It’s the same story with various types of medical equipment from scanning equipment to dialysis machines and other devices that can save lives. When a company has a monopoly on an item that can be essential to people’s health or life, it can charge an enormous price.

There is a logic to these patent monopolies: They give companies incentive to invest millions, or even billions, in developing these life-saving products. I’ll get back to this, but let’s first focus on the issue from the standpoint of society.

Suppose a drug company is charging $100,000 for a course of treatment for a serious disease. This number is not imaginary. When Sovaldi, the breakthrough drug for Hepatitis-C, was first introduced more than a decade ago, the company charged $84,000 for a three-month course of treatment, which was usually a complete cure for a debilitating and life-threatening illness. That would be well over $100,000 in today’s dollars.

If a patient told UHC, or any insurer, that it wanted it to pay $100,000 for a drug, it is understandable that it would want to scrutinize the proposed payment closely. It would want to be certain that the person actually had the condition for which they wanted treatment. Maybe it would demand verification from more than one doctor.

It would also want to be sure that the proposed treatment would actually be effective. Because of the huge markups allowed by patent monopolies, drug companies have enormous incentives to claim that their drugs are more effective than may really be the case. There may be risks for patients that drug companies conceal, as was the case with the addictiveness of the new generation of opioids. For these reasons, it is understandable that an insurer would want to make sure that the drug really was the best treatment for the patient.

The insurer would also reasonably ask if there are lower cost alternatives. If an extremely expensive drug provides only marginal benefits over a cheap generic (e.g. it need only be taken once a day rather than multiple times), it might be reasonable to insist that the patient take the cheap generic.

These issues arise because the drug can sell for a price that is far above its marginal cost. If we had Sovaldi selling for a few hundred dollars for a course of treatment, the price of generic Solvaldi, it’s unlikely the insurer would be asking many questions.

These sorts of issues arise with many of the situations where insurers decline approvals. This applies not only to drugs, but scans and the use of medical equipment. An insurer may not want to pay for a scan using the latest device but would instead insist on a simple X-ray or other cheaper scan. If there were no patents on the latest device, the cost of using it would be little different than the cost of a simple X-ray machine. In the no-patent world, there would be little reason for an insurer not to tell patients to use the best available technology.

Note that these issues would arise even if we had a single-payer system. A monopsonist buyer could force the drug companies and medical equipment manufacturers to accept lower prices, but we still would face the problem that they would be charging prices that are far above their marginal cost. In that case, there would still be good reason to carefully scrutinize the use of new drugs and medical equipment that cost far more than off-patent alternatives.

This stems from the mechanism for financing innovation. We want drug companies and medical equipment manufacturers to be able to make enough profit to give them incentive to innovate. If we forced their price down to generic levels, there would be no reason to make the investments needed to develop better drugs and medical equipment.

Another Way to Finance Innovation

We don’t have to rely on patent monopolies to finance research. There are alternative routes, most obviously direct public funding. We already spend more than $50 billion a year supporting biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health and other government agencies. The industry spends around $120 billion a year which it expects to be reimbursed through its patent monopolies. This spending would need to be replaced.

We would probably need an alternative structure to NIH for this funding. (I outline a system of long-term contracts in Rigged [it’s free], but we can debate how a system of public funding could be best structured.) However, the savings from having drugs and medical equipment available at generic prices would be enormous. We will spend over $650 billion this year on drugs and other pharmaceutical products, more than $5,000 per family. The cost would likely be in the neighborhood of $100 billion if they were sold without patent monopolies. We spend another $200 billion on medical equipment.

More important than the savings is the changed structure of incentives. Insurers, or whoever was deciding on whether to pay the tab, would be looking at the actual cost of the drug or medical device to society at the point where the patient needs it. As it is now, we are asking patients, who are almost by definition in bad health, to pay for research that might have been done (and paid for) ten or twenty years ago. That makes no sense.

We also would take away the incentive for drug companies and medical equipment manufacturers to misrepresent the safety and effectiveness of their products. This is especially the case if a requirement of getting public funding is that all research findings be fully open. In that case, the companies developing a drug or medical device would have no special access to information. The entire community of researchers would have all the same information.

Does This Fix the Healthcare System?

Having drugs and medical equipment sell at free market prices would eliminate many of the tough calls insurers make today. The insurance industry itself is still an enormous source of waste that would be eliminated with a single-payer type system, but many of the tough calls would still exist if we left our current patent monopoly system in place.

If we instead funded innovation upfront, and had cheap drugs and medical equipment, most of these tough calls would go away. There still would be cases where there are tough calls. For example, open-heart surgery can involve many hours from highly paid cardiologists and heart surgeons, as well as extensive preparation and follow-up from a number of other healthcare professionals. Should we be prepared to pay these costs for a person in their eighties or nineties?

Of course, this cost would be considerably less if we paid our doctors closer to what they get in other wealthy countries and didn’t have hospital administrators with ridiculously bloated salaries. But getting drugs and medical equipment at free market prices would be a great start in reducing the number of tough calls we have to make in deciding on medical care.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.

Lawmakers are looking to break up massive health care conglomerates that manage nearly 80 percent of prescriptions.

By Mike Ludwig ,

As we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation, your support is urgently needed. Please make a year-end gift to Truthout today.

Amid an outpouring of frustration with for-profit health insurance sparked by the assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson on December 4, much of the media coverage has focused on the alleged shooter, 26-year-old Luigi Mangione, and the industry’s nasty habit of maximizing profits by denying claims and leaving sick and vulnerable patients with massive medical bills.

There’s plenty of data to back up the anger over private health plans expressed online since the shooting. Insurance costs are far outpacing inflation, leaving patients with soaring out-of-pocket costs. Health insurance companies are notorious for exploiting prior authorization schemes to avoid paying for care and have denied claims at alarming rates in recent years.

However, corporate consolidation of industry “middlemen” that experts say are partially to blame for the prescription drug affordability crisis has received less scrutiny from the general public, despite efforts by lawmakers and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to shine light on the notoriously opaque and confusing corporate bureaucracy that determines the cost of medicine.

We often hear about Big Pharma selling drugs at high prices and insurance companies dragging their feet when it comes time to pay the bill, but the prices patients pay out of pocket for pharmaceuticals is largely shaped by the connective tissue between insurers and drug manufacturers: pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. PBMs have been around for decades, but the largest PBMs have merged with major insurance companies to form conglomerates, including UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Rx.

In theory, PBMs negotiate discounts and rebates paid by drug makers that are passed onto insurance companies and their patients, but the lack of transparency in that process has long frustrated lawmakers and regulators attempting to contain the skyrocketing cost of medicine.

Behind UnitedHealthcare’s CEO Is a Larger System of Corporate Rule

The violence of for-profit health care’s megastructure can only be overcome through collective resistance campaigns.

By Derek Seidman , TruthoutDecember 12, 2024

The PBMs say their secret negotiations with drug companies make prescriptions more affordable for consumers, but this system has not shown to protect patients from sticker shock at the pharmacy counter.

Nearly 30 percent of Americans say they haven’t taken prescribed medication due to cost, and an estimated 1.1 million Medicare patients alone could die over the next decade because they cannot afford the drugs prescribed by their doctors, according to the American Hospital Association. The FTC reports that in 2023, the U.S. spent more than $722 billion on prescription drugs, nearly as much as the rest of the world combined.

Clearly the system is not working for patients or public health, and policy makers in both parties have increasingly focused on the PBMs and their recent mergers with major insurance companies. According to a two-year FTC investigation on health care conglomerates released in July, PBMs are “powerful middlemen inflating drug costs and squeezing Main Street pharmacies.”

“We’ve heard accounts of how the business practices of PBMs may deprive patients of access to the most affordable medicines and how doctors find themselves having to subordinate their independent medical judgment to PBMs’ decision-making at the expense of patient health,” FTC Chair Lina Khan said in a statement at the time.

An estimated 1.1 million Medicare patients alone could die over the next decade because they cannot afford the drugs prescribed by their doctors.

Over the past decade, the consolidation or “vertical integration” of PBMs with major health insurers formed massive health care conglomerates that include retail and mail-order pharmacies to capture every inch of the supply chain. The FTC found that the three largest PBMs — CVS Caremark, Cigna Group’s Express Scripts and UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Rx — now manage nearly 80 percent of prescriptions filled in the United States.

PBMs leverage their management of formularies, or the list of drugs available on insurance plans, to negotiate rebate payments from drug makers that are supposed to reduce costs for patients and insurers. However, when doctors prescribe costly drugs that do not appear on an insurer’s formulary, patients can be forced to pay the full price out of pocket.

Earlier this year, New Jersey resident Ann Lewandowski sued her former employer, Johnson & Johnson, after the company’s insurance plan left her facing a $10,000 bill for a three-month supply of a name brand drug for treating multiple sclerosis. A generic version of the drug can be purchased without insurance at a cost between $28 and $77 at major pharmacies, according to the lawsuit, but these options were not available due to the PBM policy.

“They will tell you their mission is to lower drug costs,” said Rep. Earl L. “Buddy” Carter (R-Georgia), a pharmacist and a critic of PBMs, in a speech on the House floor in 2019. “My question to you would be: How is that working out?”

Critics say negotiations with PBMs incentivize drug companies to inflate the “list price” or market price of drugs, creating an ever-widening gap between the list and the “net price,” which is the cost insurance companies and patients often share through various copay schemes.

This process famously pushed up the price insulin for years until the drug became unaffordable for diabetes patients who need it to survive. Congress stepped in after much public outcry — in 2019 patients traveled to Canada with Sen. Bernie Sanders to find insulin they could afford — and in 2022 President Joe Biden signed legislation capping insulin copays at $35 for Medicare patients.

Dragged before Congress and facing protests by angry patients and public health groups over the price of insulin, drug companies pointed the finger of blame at PBMs. Merck Chief Executive Kenneth Frazier told the Senate Finance Committee in 2019 that PBMs benefit when the list price of drugs goes up, creating a preference within the supply chain for higher priced medicines.

“This kind of misalignment can have a significant negative impact on patients because their cost sharing is often based on the list price of a drug, even when insurance companies and PBMs are paying a fraction of that price,” Frazier said. “Our current system that incentivizes high list prices and large rebates as a mechanism to keep insurance premiums low means that sick patients are essentially subsidizing healthy patients.”

While it remains unclear how much money PBMs keep for themselves as “middlemen,” critics tend to blame the entire supply chain, including Merck and other drug makers, when medicine is unaffordable. However, the recent integration of the largest PBMs with top insurers has consolidated an alarming level of corporate control over that supply chain, according to Unai Montes-Irueste, a spokesman for the People’s Action Institute’s Care Over Cost campaign.

“It’s a horizontal and vertical monopoly they are creating, so they are able to skim profit or take profit and grow profit at every stage and in every direction,” Montes-Irueste said in an interview.

Following its investigation, the FTC filed an administrative lawsuit in September against the top three PBMs alleging unfair and anti-competitive rebating practices that have artificially increased the list price of insulin and shifted the burden onto vulnerable patients. The PBMs responded with a lawsuit in federal court that challenges the FTC’s administrative process and accuses the agency of regulatory overreach.

The merger of large PBMs with insurers is also blamed for creating “pharmacy deserts” in rural and underserved areas where independent pharmacies that locals relied on for years went out of business. In February, the National Community Pharmacists Association declared an “emergency” and warned Congress that the monopolistic practices of health insurers and their PBMs must be regulated or thousands of pharmacies could close their doors.

“Pharmacists from West Virginia to Texas have written to the FTC, expressing concern that PBMs’ business practices are creating risk for their patients while squeezing independent pharmacies that have served their communities for decades,” Khan said in July.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) and Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) introduced bipartisan legislation on December 11 that would break up the monopoly on pharmacy access that the top three PBM and insurer conglomerates are building. The bill would prohibit companies that own both a PBM and insurance business from owning retail or mail-order pharmacies at the end of the supply chain. If enacted, the health care conglomerates would be required divest from their pharmacies within three years.

“If from the moment something is prescribed to when it is received by the patient it is always a source of profit, then it’s a thousand-layer cake,” Montes-Irueste said.

Multiple states have passed their own laws, but Montes-Irueste said the drug affordability crisis requires a federal solution for powerful, nationwide industry. The $35 cap on insulin copays for Medicare patients was badly needed, but the health conglomerates simply found ways to squeeze profits out of other patients.

“There are 999 layers of that cake that is not regulated and one is, and that one that is regulated is under threat by the new administration,” Montes-Irueste said.

Now policy makers must focus on lowering the out-of-pocket cost that patients pay for other lifesaving drugs, Montes-Irueste said, but that could be difficult under President-elect Donald Trump and a GOP-controlled Congress. However, the recent conversation around health insurers could prove to be an opportunity.

“We have found a place in public policy where we do not have a left-right question, we have a top-down question,” Montes-Irueste said. “We are in a moment when we can say clearly to private corporations, ‘stop denying care,’ but also that government actors must offer solutions at the scale of need.”

The scale of need is being spelled out right now by the millions of online comments from people who feel like the health insurance system is broken, Montes-Irueste said. “And for those who profit out of, it is working perfectly.”

The violence of for-profit health care’s megastructure can only be overcome through collective resistance campaigns.

By Derek Seidman ,

The killing of UnitedHealthcare’s Brian Thompson — a brazen assassination of a wealthy CEO in the streets of midtown Manhattan — shocked the United States. But the tsunami of mass anger unleashed against a hated for-profit health care system has so far defined the story in the news. The killing sparked a deluge of personal testimonies of horrifying experiences with health insurance corporations. Dark humor around the shooting continues to flood social media.

Millions of people in the U.S. viscerally hate health insurance corporations, and see these companies and their CEOs as symbols of the worst kind of corporate greed. They enrich themselves by charging huge deductibles and then still denying claims for health care coverage that people desperately need. These corporations hold the power to ruin lives. It seems as if almost everyone in the U.S. has had a horrible experience with a health insurance corporation.

UnitedHealth Group — the parent company of UnitedHealthcare — is a poster child for this system. It is the biggest health insurance corporation in the U.S. Its top executives rake in tens of millions of dollars. UnitedHealth Group has faced scrutiny for a range of alleged abuses, such as overcharging on Medicare bills and using AI to reject medically necessary coverage. It’s a leader in an industry that moves to crush any talk of a single-payer health care system.

It’s critical to understand the practices of UnitedHealth and the wider health insurance industry as systemic and bound up with the larger ensemble of corporate rule. The problem isn’t just that health insurance CEOs callously deny coverage to patients to extract massive profits — it’s that if those CEOs didn’t do this, their boards of directors and shareholders would demand their replacement.

UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was just one cog within a larger structure of company executives, corporate board directors, big investors, and an army of lobbyists and industry groups — all bent on preserving the system of private, for-profit U.S. health care that is nearly universally detested and requires collective organizing action to be dismantled.

Poll: Nearly 2 in 3 Americans Say Government Should Ensure Health Care Coverage

The US is the only wealthy country in the world without universal health care.

By Sharon Zhang , Truthout December 10, 2024

UnitedHealth Group is a massively profitable corporation. From 2021 to 2023 it took in nearly $1 trillion in revenue and nearly $60 billion in profits. Last quarter it generated over $100 billion in revenue and $6 billion in profits. It ranks fourth on the Fortune 500 list of top U.S. companies.

The CEO of UnitedHealth — and, as head of UnitedHealthcare’s parent company, Thompson’s boss — is Andrew Witty, who was awarded a knighthood in 2012 by the British royal family and who hobnobs with Bill Gates and advises his foundation.

From 2021 to 2023, Witty raked in nearly $63 million as UnitedHealth’s CEO. Witty’s 2023 compensation of $23,534,936 was 352 times the median employee pay at UnitedHealth. By comparison, Thompson took in just under $30 million from 2021 to 2023.

Witty owns 97,172 shares of UnitedHealth stock, currently worth around $54 million, even as the company’s share value took a hit after Thompson’s killing. (It had reached an all-time high just weeks before.)

UnitedHealth CEOs have a history of receiving astronomical levels of compensation. Stephen J. Hemsley served as UnitedHealth CEO from 2006 through 2017, during which he came under scrutiny for taking home $102 million in 2009 after exercising stock options.

The problem isn’t just that health insurance CEOs callously deny coverage to patients to extract massive profits — it’s that if those CEOs didn’t do this, their boards of directors and shareholders would demand their replacement.

Today, Hemsley remains a powerful figure at UnitedHealth, serving as chair of its board of directors. In 2023, he raked in a whopping $113 million after selling off more of his UnitedHealth stock.

While UnitedHealth’s executives receive huge compensation, they’re not unique within the sector. For example, from 2021 to 2023, the CEOs of the next three largest U.S. health insurers were similarly compensated: Elevance Health’s CEO received over $61 million, CVS Health’s CEO received over $63 million and Cigna’s CEO received over $61 million.

Boards of Directors

Witty and other top UnitedHealth executives, in turn, answer to an even higher authority: UnitedHealth’s board of directors.

Corporate boards are companies’ highest governing bodies. They hire and review top executives and set their compensation. They are tasked with oversight of overall business and strategic risks. Board members annually receive hundreds of thousands of dollars for their board service.

Company boards are interlocked with larger structures of corporate rule. While UnitedHealth is a discrete entity, it’s also a node in a wider web of corporate power — a fact illustrated in the composition of its 10-member board of directors.

For example, one UnitedHealth director, Timothy Flynn, is the retired CEO of KPMG International, one of the “Big 4” global accounting firms. He was a board director of JPMorgan Chase, the world’s top bank, from 2012 to 2024. As of March 2024, Flynn owned JPMorgan stock worth over $17 million today, and he also owns nearly $7 million in UnitedHealth stock.

Since 2012, Flynn has also sat on the board of Walmart, the world’s top retailer and a notorious union buster, and he owns over $14 million in Walmart stock. He previously served on the boards of aluminum giant Alcoa and insurance powerhouse Chubb, which, along with JPMorgan, have been primary targets of climate protesters for financing and insuring the fossil fuel industry.

Another UnitedHealth director, William McNabb, is the former CEO of Vanguard Group, the world’s second-largest asset manager, and also the top shareholder of UnitedHealth. McNabb is also a board director of computer giant IBM. He owns over $3 million in IBM stock and over $7 million in UnitedHealth stock.

Stephen J. Hemsley, the former UnitedHealth CEO mentioned above, not only chairs UnitedHealth’s board, but is also on the board of Cargill, the largest privately held company in the U.S. Other corporations represented on UnitedHealth’s board, either through current or previous ties to directors, include Google, United Airlines, PPG Industries, Global Payments, SunTrust and Merck.

Like many corporate boards, UnitedHealth has a revolving door politician in former Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, who joined the company’s board immediately after his last term ended in 2023.

While company CEOs understandably draw popular ire, they are both incentivized and disciplined by their boards of directors — through bonuses and stock incentives, but ultimately the possibility of termination — toward delivering maximum profits for investors and keeping share prices up. In other words, under this system, if Andrew Witty or Brian Thompson don’t gouge insurance customers, the board will find CEOs who will.

Big Shareholders

Even UnitedHealth’s board of directors has a higher authority: the company’s investors.

As a publicly traded corporation, UnitedHealth is effectively owned by its shareholders, composed primarily of the largest asset managers and Wall Street banks. UnitedHealth regularly sends billions back to investors — and its own executives and directors — through stock buybacks and dividend payouts.

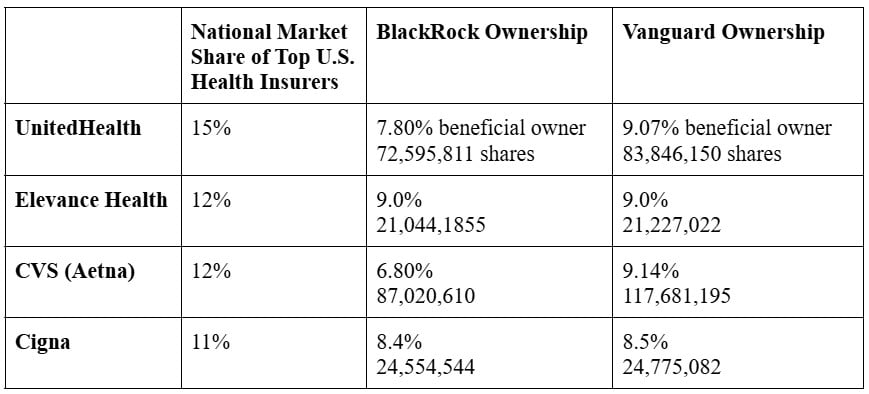

The two top shareholders of UnitedHealth are the world’s two biggest asset managers, BlackRock and Vanguard, which together oversee more than $20 trillion in assets. According to UnitedHealth’s most recent proxy statement, Vanguard is a 9.07 percent beneficial owner of UnitedHealth and BlackRock is a 7.8 percent beneficial owner.

Together, these two firms alone beneficially own around 17 percent of UnitedHealth, holding a combined 156,441,961 shares of UnitedHealth stock worth over $87 billion.

And it’s not just UnitedHealth: BlackRock and Vanguard are the top two shareholders of the top four U.S. health insurers in terms of national market share.

All told, BlackRock and Vanguard are 16-19 percent beneficial owners of four corporations that control half of the U.S. health insurance market.

Other Wall Street firms, like Fidelity, State Street, JPMorgan, and others are also huge shareholders of UnitedHealth and the other health insurance giants — just typically more in the 2-4 percent range.

The top 10 shareholders of UnitedHealth together have a 41 percent ownership stake in the corporation. Some of these firms are led by hugely influential billionaires, including BlackRock’s Larry Fink, Fidelity’s Abigail Johnson and JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon.

While these top shareholders in health insurance corporations are so-called passive investors who invest widely across the entire corporate spectrum, they hold the power to compel changes around exploitative companies and industry practices if they choose so.

Lobbyists and Campaign Donations

UnitedHealth can only pursue its insatiable quest for profits with the assistance of well-compensated lobbyists.

In 2023 and 2024 alone, UnitedHealth has spent $23,885,000 on federal lobbying carried out by an in-house lobbying team and nine outside lobbying firms. These lobbyists include influential former government officials and staffers with bipartisan ties.

On the Democratic side, UnitedHealth lobbyists include the former chief of staff for House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries; the former director of legislative Affairs for then-Vice President Joe Biden; the former executive director of Nancy Pelosi’s campaign committee; the former chief of staff to former congressman and top Biden administration adviser Cedric Richmond; and a top fundraiser for House Democrats who is the former chief of staff to former House Democratic Leader Dick Gebhardt.

On the Republican side, UnitedHealth lobbyists include the former chief of staff for Sen. Mitch McConnell; the former chief of staff for Sen. Ted Cruz; and several officials from George W. Bush’s administration.

To take on this megastructure, we will have to build our own counterstructures, like grassroots and labor single-payer campaigns, debtor organizations, trade unions and tenant groups.

Additionally, in the 2024 election cycle, UnitedHealth’s PAC donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to federal and state politicians across the political aisle, including $15,000 each to both Democratic and Republican House and Senate campaign committees. They also gave thousands to key congressmembers who sit in influential positions on committees that oversee and regulate the health care industry.

Industry Groups

However, much of the heavy lifting of defending the interests of health insurance corporations isn’t done by individual companies, but by their industry groups.

These industry groups unite the resources of entire corporate sectors to advance their agenda with a single voice. Big Oil has the American Petroleum Institute. Big landlords have the National Multifamily Housing Council. For health insurers, the key industry group is America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

AHIP’s board is composed of the CEOs from top U.S. health insurance companies. The president and CEO of AHIP is a former top executive from UnitedHealth, and the head of AHIP’s federal lobbying operation also previously worked for UnitedHealth.

AHIP has spent over $26 million lobbying the federal government in 2023 and 2024, using in-house lobbyists and — like UnitedHealth — hiring nine outside lobbying firms similarly filled with former government staffers and officials. AHIP is also a major donor to political parties and elected officials, including the Democrats and their top leaders.

As the vehicle for defending the generalized corporate interests of health insurers, AHIP tries to destroy anything that threatens the for-profit health care system, especially single-payer health care.

In June 2018, AHIP joined other health care industry groups like Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the Federation of American Hospitals to create the Partnership for America’s Health Care Future, an astroturf operation aimed at crushing Medicare for All.

Taking on the System

Some health insurance executives are lamenting that they’re being cast as villains for simply “playing their role in the system,” according to The New York Times. What’s omitted here is that health insurance corporations are not passive functionaries within the U.S. for-profit health care system, but active defenders of that system that mobilize campaign donations, lobbyists and industry groups to stamp out alternatives like a single-payer system that would cut out rapacious middleman profiteering from health care.

But the current groundswell of anger around the U.S. health care system should embolden new efforts to push for a single-payer, Medicare for All system — a demand for systemic change that could be a unifying anchor for a broad challenge to Trumpism and corporate rule exercised through both political parties.

UnitedHealth and other health insurance companies are part of a larger apparatus of corporate rule that must be combated through collective action focused on building the power needed to achieve systemic change. To take on this megastructure, we will have to build our own counterstructures, like grassroots and labor single-payer campaigns, debtor organizations, trade unions and tenant groups, and engage in confrontational political efforts and general strikes.

It’s clear we are living in a period of rising anti-systemic feelings and widespread anger at corporate profiteering over every aspect of our lives, from health care to housing to work. The time is ripe for building the collective organizations and capacities we need to challenge the structures that reward and enable corporate CEOs’ abuses.

.jpg)