Three-quarters of Earth’s land has become drier since 1990.

Droughts come and go – more often and more extreme with the incessant rise of greenhouse gas emissions over the last three decades – but burning fossil fuels is transforming our blue planet. A new report from scientists convened by the United Nations found that an area as large as India has become arid, and it’s probably permanent.

A transition from humid to dry land is underway that has shrunk the area available to grow food, costing Africa 12% of its GDP and depleting our natural buffer to rising temperatures. We have covered several consequences of humanity’s fossil fuel addiction in this newsletter. Today we turn to the loss of life-giving moisture – what is driving it, and what we are ultimately losing.

Why is the land drying out so fast? It’s partly because there is more heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gases emitted from burning fossil fuels. This excess heat has exacerbated evaporation and is drawing more moisture out of soil.

‘Oil, not soil’

Climate change has also made the weather more volatile. When drought does cede to rain, more of it arrives in bruising downpours that slough the topsoil.

A stable climate would deliver a year’s rain more evenly and gently, nourishing the soil so that it can nurture microbes that hold onto water and release nutrients.

This is the kind of soil that industrial civilisation inherited. It’s disappearing.

“Soil is being lost up to 100 times faster than it is formed, and desertification is growing year on year,” says Anna Krzywoszynska, a sustainable food expert at the University of Sheffield.

“The truth is, the modern farming system is based around oil, not soil.”

Fossil fuels have unleashed agriculture from the constraints of local ecology. Once, the nutrients that were taken from the soil in the form of food had to be replaced using organic waste, Krzywoszynska says. Synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, made with fossil energy at great cost to the climate, changed all that.

Next came diesel-powered machinery that brought more wilderness into cultivation. Farm vehicles as heavy as the biggest dinosaurs now churn and compact the soil, making it difficult for earthworms and assorted soil organisms to maintain it.

Tractors and chemicals served humanity for a long time, Krzywoszynska says. But soil is now so degraded that no amount of fossil help can compensate.

“Across the world, soils have been pushed beyond their capacity to recover, and humanity’s ability to feed itself is now in danger.”

Green pumps and white mirrors

The primary way that we have been making up for lost food yield is turning more forests into farms. This is accelerating our journey towards a drier, less liveable world because forests, if allowed to thrive, create their own rain.

“Water sucked up by tree roots is pumped back into the atmosphere where it forms clouds which eventually release the water as rain to be reabsorbed by trees,” say Callum Smith, Dominick Spracklen and Jess Baker, a team of biologists at the University of Leeds who study the Amazon rainforest.

“In the Amazon and Congo river basins, somewhere between a quarter and a half of all rainfall comes from moisture pumped from the forest itself.”

Some experts have argued that the UN report understates Earth’s growing aridity by overlooking the water that is held in snow caps, ice sheets and glaciers. Climate change is melting this frozen reservoir, which also serves as a seasonal source of water.

“And as water in its bright-white solid form is much more effective at reflecting heat from the sun, its rapid loss is also accelerating global heating,” says Mark Brandon, a professor of polar oceanography at The Open University.

How do we adapt our relationship with the land to remoisturise the world? Krzywoszynska argues that there is no easy solution, but the future of food-growing “is localised and diverse”.

“To ensure that we eat well and live well in the future, we’ll need to reverse the trend towards greater homogenisation which drove food systems so far.”

The good news, according to Krzywoszynska, is that farmers are experimenting with methods that restore the soil even as they produce a diverse range of nutritious food. These innovators need rights and secure access to the land, the opportunity to share their experiences and financial and political support.

“Regenerating land is a win-win, for humans and their ecosystems, if we dare to look beyond the immediate short-term horizon,” she says.

On February 8, 2024, Earth reached a new milestone. The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported that mean temperature in the previous 12 months had been more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. As the Progressive International (2024) commented, “Just nine short years ago, the world’s governments agreed in Paris that they would limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees. ‘1.5 to stay alive’ was the mantra. They failed in record time.”

In fact, the World Meteorological Organization’s State of Global Climate 2023, issued in March 2024, reports a plethora of records broken, even smashed, for greenhouse gas levels, ocean heat and acidification, surface temperatures, sea level rise, glacier retreat, and Antarctic Sea ice cover (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). These ‘records’ are broken at our peril, and indeed, the human dimensions of climate change are also undeniable. As the report observes, in 2023 “heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires, and intense tropical cyclones wreaked havoc on every continent and caused huge socioeconomic losses” (World Meteorological Organization, 2024:iii).

The consequences were particularly devastating for vulnerable populations, as “extreme climate conditions exacerbated humanitarian crises, with millions experiencing acute food insecurity and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes” (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). It is hardly surprising that nearly 80 percent of the world’s leading climate scientists, when polled in the spring of 2024, foresaw a global temperature increase of at least 2.5 degrees Celsius by end of century. The vast majority of the most knowledgeable people on our planet “expect climate havoc to unfold in the coming decades” (Carrington 2024).

Hothouse Earth

In 2018, a team of earth scientists introduced the term “Hothouse Earth,” in a widely cited article. They noted a rapid advance toward planetary thresholds at which “intrinsic bio-geophysical feedbacks in the Earth System … could become the dominant processes controlling the system’s trajectory” (Steffen et al. 2018:8254). These thresholds are called ‘tipping points’, beyond which climate change accelerates and becomes irreversible, in a cascade of positive feedback. The feedback processes include permafrost thawing, which releases methane (a greenhouse gas 84 times more impactful than CO2) and loss of polar ice sheets, which is not only elevating sea levels but weakening the albedo effect.1 As the planet warms, increased atmospheric methane and shrinking polar ice caps, triggered by global heating, amplify global heating.

There are other feedback loops. Climate chaos already underway (drought, wildfires) contributes to the die-back of tropical and boreal forests – turning ecosystems that have fixed carbon for millennia into grasslands and carbon bombs. Meanwhile, increasing volumes of atmospheric carbon precipitate as acid rain, reducing the oceans’ capacity to absorb carbon, and further heating the hothouse.2 Steffen et al noted that “Hothouse Earth is likely to be uncontrollable and dangerous to many … and it poses severe risks for health, economies, political stability … and ultimately, the habitability of the planet for human” (2018:8257). The challenge for humanity is to create “a ‘Stabilized Earth’ pathway that steers the Earth System away from its current trajectory toward the threshold beyond which is Hothouse Earth” (2018:8254).

Ecocide

The situation has been described as climate crisis, climate breakdown, climate emergency but, most ominously, as ecocide. In the scholarly literature, ‘ecocide’ emerged as a term in 1970 (Weisberg 1970) but was rarely invoked in the titles of academic articles and books until recent years.3 In his eponymously titled book, David Whyte defined ecocide as “the deliberate destruction of our natural environment” (2020:2), and pointed his finger directly at the profit-driven corporations that “are wrecking our world” (2020).

Stop Ecocide International, a movement organization campaigning to make ecocide an international crime, defines the term as “the mass damage and destruction of the natural living world,” literally “killing one’s home” (Stop Ecocide n.d.). Ecocide does not mean the end of nature, which is indifferent to any particular species, including ours. Nor is the prospect of ecocide a death sentence for all of humanity. Just as genocide – a term painfully familiar to us from contemporary Palestine – does not mean the annihilation of an entire ethnic group, ecocide implies the destruction of the conditions for a decent life for vast numbers of people. The growing numbers of climate refugees from regions that are already becoming uninhabitable – whether from sea level rise or desertification – confirm that ecocide is already upon us, in its earliest stage.

Ecocide is very much about the Earth’s prospects of supporting a large population of humans, but other species are already in sharp decline. Drawing on the most recent figures from the Living Planet Index,4 Patrick Greenfield (2022) notes that between 1970 and 2018 “wildlife populations have plunged by an average of 69%”; “the abundance of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles is falling fast, as populations of sea lions, sharks, frogs and salmon collapse.” Indeed, the climate crisis is entirely entangled with the Sixth Extinction, the cumulative decline of living systems – and of biodiversity – as forests are cleared to make room for cattle grazing, reducing biodiversity, impairing the Earth’s ‘lungs’ from fixing atmospheric carbon and increasing carbon emissions. Elizabeth Kolbert writes, in her Pulitzer Prize winning The Sixth Extinction:

“Having freed ourselves from the constraints of evolution, humans nevertheless remain dependent on the earth’s biological and geochemical systems. By disrupting these systems – cutting down tropical forests, altering the composition of the atmosphere, acidifying the oceans – we’re putting our own survival in danger.” (2014:267)

Although the Sixth Extinction looms in the background, this book is laser-focussed on the single most urgent ecological and existential challenge of our time: the climate crisis, its human causes, and the possibilities for refusing this cardinal element of ecocide.

The climate crisis is a natural phenomenon, driven by human activities (which, as I will explain in Chapter 1, are also natural phenomena). This has led many earth scientists to argue that the planet has crossed into a new epoch, the Anthropocene – that of the ‘geology of mankind’ – (Crutzen 2002), “beginning around 1950, representing the emergence of human-industrialized society as the primary factor in Earth System change” (Foster 2024:249). Critical social scientists, however, have noted that this term can be misleading. It fails to identify the specific human agents, operating within social structures, who are the primary drivers of the crisis. Andreas Malm (2016:391) suggests, “this is the geology not of mankind, but of capital accumulation.”

Drive for Capital Accumulation

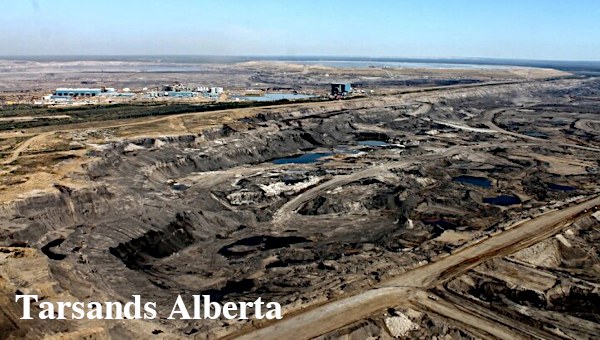

Certainly, the corporations that dominate the fossil fuel sector, and their predecessor firms, are the major culprits. In 2014, Richard Heede published an article documenting that between 1751 (before the invention of the steam engine) and 2010 the 90 biggest emitters – the ‘carbon majors’ – were responsible for 63% of cumulative worldwide emissions of greenhouse gases, with half of all emissions having been released since 1986. In the seven years following the 2015 Paris climate accord, the carbon majors increased their emissions; indeed 80% of global emissions from 2016 through 2022 “can be traced to just 57 corporate and state producing entities,” demonstrating “the outsized influence of a small group of producers that are increasing production” (InfluenceMap 2024:4, 26). Their investment decisions have directly caused the climate crisis, and continue to exacerbate it. The CEOs of these fossil-fuel producers could fit into a couple of school buses.

But the carbon majors are enabled by other actors and institutions. At the Corporate Mapping Project, a community-university research and public engagement project I co-directed from 2015 to 2023 (Carroll and Daub 2015; Carroll 2021), we mapped the various connections between the fossil-fuel sector and the economic, political, and cultural organizations that enable and legitimate its activities, focussing on the case of Canada, a major fossil-fuel producer. In Chapter 4, I reflect on some of our findings, which reveal a “regime of obstruction” that enables and protects the revenue streams and fixed-capital investments of fossil-fuel corporations and blocks meaningful climate action. The key actors in this regime include the banks and institutional investors that finance the industry, the captured regulators that green-light new investments, the government ministries in regular dialogue with industry lobbyists, and a range of organizations that legitimate the industry, from think tanks, industry groups, and business councils to corporate and astro-turf media and business schools.

This book focusses on these centres of economic, political, and cultural power. I analyze how their actions have driven the climate crisis, and why the ruling economic and political bloc, based in the advanced capitalist west, or global North, is incapable of steering humanity to a safe destination. Ecocide, however, is not inevitable. In recent decades, many initiatives have appeared in resistance and opposition to ecocidal practices. These include:

- grassroots movements and street actions to raise consciousness and pressure governing elites, such as Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future;

- more organized popular opposition grounded in the left, such as like Trade Unions for Energy Democracy, the Global Ecosocialist Network, and the Climate Justice Alliance;

- online platforms that offer critical policy analysis focussed on the fossil-fuel industry and its allies, enablers, and legitimators, such as Oil Change International, InfluenceMap and the Climate Social Science Network; and

- alternative media focussed on the ecological crisis, such as Desmog, Green Left, and Climate&Capitalism.

However, in the dominant institutions, including the annual Convention of the Parties (COP) that governs the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, corporate interests predominate, fettering the transformations that are obviously necessary. At COP 28, held in Dubai in December 2023, a record number of fossil fuel lobbyists (2,456 in all) outnumbered all national delegations but those of the host and host-designate. Dwarfing all official Indigenous representatives 7-to-1, those lobbyists found ready allies among the many fossil-fuel employees embedded in the national delegations of France, Italy, and other Northern countries (Corporate Europe Observatory 2023). Not surprisingly, COP 28, like all previous COPs,

“failed to agree on the need to phase out fossil fuels and to set a deadline for doing so. Instead, the final document suggests that states may – with no obligations – ‘draw down’ fossil fuel production. The demands from over 120 countries to completely eliminate new fossil fuel production were ignored.” (Progressive International, 2023)

The chasm between the urgency of serious climate action, understood by many, and the stasis of climate policy at global and national levels is palpable. Why this stasis, and what is to be done?

What Is To Be Done?

This book addresses these questions, in two parts. The first develops a critical perspective on fossil capitalism and climate breakdown, drawing primarily on the historical materialist framework first introduced by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. This framework directs our attention toward a ‘trifecta of power’ at the centre of capitalism as a way of life, illuminated via three core concepts. Capitalist accumulation, the economic aspect, is driven by the private profit motive toward endless growth and increasing inequities. Imperialism, the geo-political-economic aspect, entails the domination of the global South by advanced capitalist states as they strip the land of resources and super-exploit cheap labour. Finally, hegemony, the cultural and political aspect, organizes popular consent to the capitalist way of life, particularly in the global North.

In Chapter 1, I unpack that trifecta, and apply it in recounting the century-and-a-half epoch from the Industrial Revolution to the close of World War Two, during which fossil capitalism was fully established. Chapter 2 takes up the post-war era – the ‘golden years’ of economic prosperity, consumer capitalism and class compromise, from the mid-1940s into the 1970s, during which the Great Acceleration took shape, exponentially increasing carbon emissions and trending toward ecological overshoot.5 The final chapter in Part 1 brings us up to date. Powered by fossil fuels, capital has subjected the world to its predatory logic, eventuating in today’s deep civilizational crisis. In the 1980s and 1990s, the economic crisis of the 1970s was resolved through neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatization and austerity, as capital became more globalized and financialized. Although the global financial meltdown of 2008 discredited neoliberalism, no alternative has gained favour in the centres political-economic power. As climate breakdown becomes increasingly visible, and as a diverse array of movements for climate justice and sanity intensify hegemonic struggle, the neoliberal zombie stumbles toward the precipice.

The book’s second part appraises solutions to the climate crisis that have been proposed from various quarters. In these chapters I examine how proposed remedies square with our core analytical concepts of accumulation, imperialism and hegemony. This engagement with alternatives begins in Chapter 4 with a critique of the ‘false solutions’ comprising Climate Capitalism: attempts to regulate fossil capital via market mechanisms or to create techno-fixes, as in changing the energy source without addressing the socio-ecological relations at the heart of the crisis. The rejection of these approaches, which remain within the logic of accumulation, imperialism and bourgeois hegemony, leads to the final two chapters. Chapter 5 explores three alternatives that move us in the right direction, yet fail to provide the comprehensive approach that the civilizational and climate crisis actually demands. These projects – the Green New Deal, Degrowth, and Buen Vivir – each contain currents that could converge upon a refusal of ecocide.

The challenge lies in pulling these social forces into a coherent hegemonic project with a mass base. Chapter 6 takes up this challenge. I argue for a democratic eco-socialism that breaks decisively from both fossil capitalism and Climate Capitalism. A capacious eco-socialist project directly confronts the trifecta of power that is at the heart of ecological degradation and social injustice. It is our best bet, against lengthening odds, in refusing ecocide. •

This is an excerpt from William K. Carroll Refusing Ecocide: From Fossil Capitalism to a Liveable World, (London: Routledge, 2025).

References

- Canada. 2011. Canada’s State of the Oceans Report, 2012. Ottawa: Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

- Carrington, Damian. 2024. “World’s Top Climate Scientists Expect Global Heating to Blast Past 1.5C Target.” The Guardian. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- Carroll, William K. 2021. “Introduction.” in Regime of Obstruction, edited by W. K. Carroll. Edmonton: AU Press, pp. 3–31.

- Carroll, William K., and Shannon Daub. 2015. “We’re Putting Fossil Fuel Industry Influence under the Microscope.” Corporate Mapping Project. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- Corporate Europe Observatory. 2023. “Record Number of Fossil Fuel Lobbyists Granted Access to COP28 Climate Talks.” Corporate Europe Observatory. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- Crutzen, Paul J. 2002. “Geology of Mankind.” Nature 415(6867):23–23. doi:10.1038/415023a

- Earth Overshoot Day. 2024. “How Many Earths? How Many Countries?” Earth Overshoot Day. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- Foster, John Bellamy. 2024. The Dialectics of Ecology: Socialism and Nature. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Greenfield, Patrick. 2022. “The Biodiversity Crisis in Numbers – a Visual Guide.” The Guardian. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- Heede, Richard. 2014. “Tracing Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide and Methane Emissions to Fossil Fuel and Cement Producers, 1854–2010.” Climatic Change 122(1–2):229–41. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0986-y

- InfluenceMap. 2024. “The Carbon Majors Database: Launch Report.” Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- Kashiwase, Haruhiko, Kay I. Ohshima, Sohey Nihashi, and Hajo Eicken. 2017. “Evidence for Ice-Ocean Albedo Feedback in the Arctic Ocean Shifting to a Seasonal Ice Zone.” Scientific Reports 7(1):8170. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08467-z

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2014. The Sixth Extinction. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Malm, Andreas. 2016. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming. Verso.

- Progressive International. 2023. “PI Briefing No. 50 COP Out.” Progressive International. Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- Progressive International. 2024. “PI Briefing | No. 6 | 1.5 to Stay Alive?” Progressive International. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- Steffen, Will, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, Timothy M. Lenton, Carl Folke, Diana Liverman, Colin P. Summerhayes, Anthony D. Barnosky, Sarah E. Cornell, Michel Crucifix, Jonathan F. Donges, Ingo Fetzer, Steven J. Lade, Marten Scheffer, Ricarda Winkelmann, and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. 2018. “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(33):8252–59. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810141115

- Stop Ecocide. n.d. “What Is Ecocide?” Stop Ecocide. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- Weisberg, Barry. 1970. Ecocide in Indochina: The Ecology of War. San Francisco: Canfield Press.

- Whyte, David. 2020. Ecocide: Kill the Corporation before It Kills Us. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- World Meteorological Organization. 2024. “State of the Global Climate 2023.” Retrieved May 2, 2024.

Endnotes

- As Kashiwase et al. (2017:8170) explain, “Ice-albedo feedback is a key aspect of global climate change. In the polar region, a decrease of snow and ice area results in a decrease of surface albedo, and the intensified solar heating further decreases the snow and ice area.”

- Each year, about one third of the carbon dioxide (CO2) in fossil fuel emissions dissolves in ocean surface waters, forming carbonic acid and increasing ocean acidity. Over the next century or so, acidification will be intensified near the surface where much of the marine life that humans depend upon live’ (Canada 2011:10).

- From 1970 to 1990 ‘ecocide’ appeared in titles of 49 articles and books in the Google Scholar database. The term was used in titles of 187 publications between 1991 and 2010. From 2011 to 25 April 2024, 770 academic publications included ‘ecocide’ in their titles (393 since 2021; search conducted on 25 April 2024).

- livingplanetindex.org, accessed 26 April 2024.

- The Global Footprint Network estimates that “humanity is using nature 1.7 times faster than our planet’s biocapacity can regenerate. That’s equivalent to using the resources of 1.7 Earths.” For everyone on the planet to live like the average American or Canadian would require 5.1 Earths (Earth Overshoot Day 2024).

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate