Photo by Gabriella Clare Marino on Unsplash

red white and black graffiti

November 25, 2024

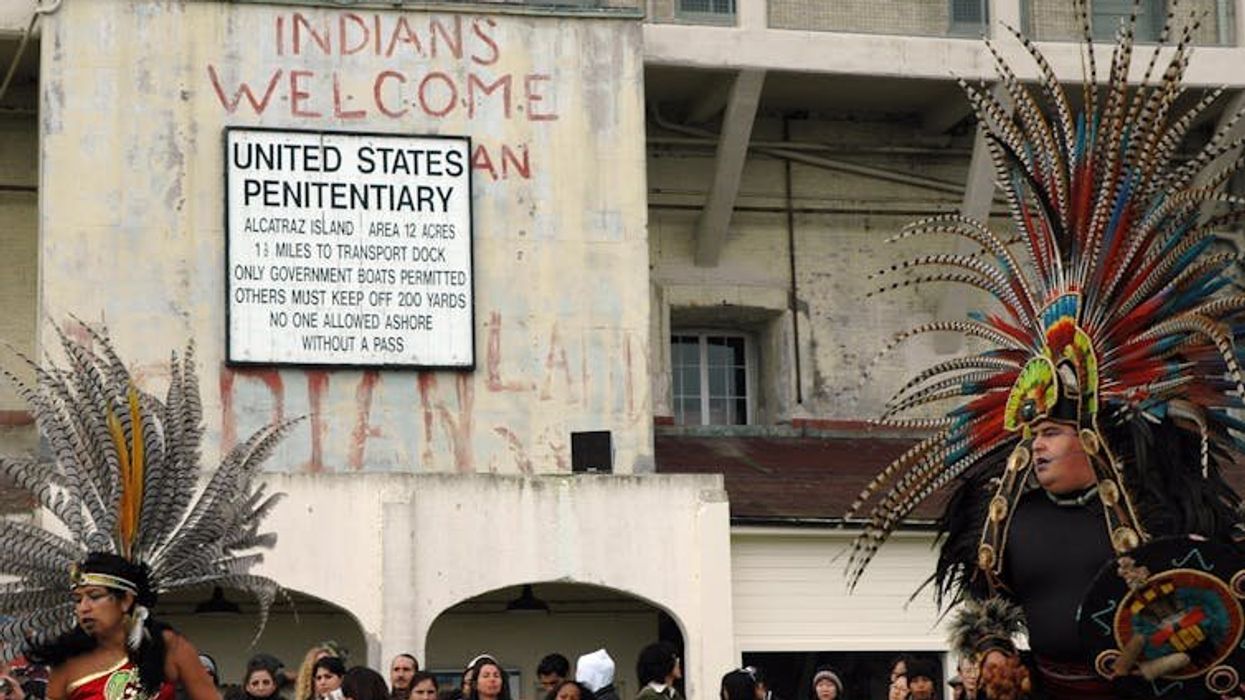

Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II features a scene in which a senator, seated at a pavement cafe in Rome, reads a printed newspaper. The moment has caused history buffs around the world to wince – the printing press wouldn’t be invented for another 1,200 years. But the film also depicts a much more authentic form of mass communication in the ancient city: writing on walls.

This includes not only the formal and well-planned inscriptions shown on buildings and triumphal arches, but the informal scratchings, painted notices and charcoal messages scribbled on the walls of the city.

The hero of the first Gladiator film, Maximus (played by Russell Crowe in 2000), has his name crudely carved onto his makeshift secret tomb in the Colosseum. Elsewhere his name has been erased from a list of gladiatorial victors in a parody of damnatio memoriae, the process by which the name and image of a person was removed from public inscriptions and buildings.

This is rather like the way the real Emperor Geta (played by Joseph Quinn) had his name and image erased from Rome following his murder at the hands of his brother Caracalla (Fred Hechinger).

Latin-literate viewers may spot a particularly obscene threat to the emperors – “irrumabo imperatores” – painted on an external wall of Rome in the background of one scene. This most likely draws on Roman poet Catullus’s Poem 16, a work deemed so offensive that it wasn’t even translated into English until the 20th century.

While the language may seem gratuitous – it roughly translates as “I will orally fuck the emperors” – this is precisely the sort of vernacular that survives on the walls of Pompeii. Archaeologists have uncovered quotes from the poet Virgil, greetings to friends, price lists, practice alphabets, the scribbled drawings of children and the doodling of adults. Yet much of the graffiti would not look out of place on the back of a toilet door.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the walls of Pompeii’s brothel were a particular hot-spot for sexual graffiti.

One anonymous customer boasts that he had “fucked many girls there”, but similar comments are found on the walls of taverns, bathhouses and in the slightly shady area of tombs on the roads just outside of Pompeii.

Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II features a scene in which a senator, seated at a pavement cafe in Rome, reads a printed newspaper. The moment has caused history buffs around the world to wince – the printing press wouldn’t be invented for another 1,200 years. But the film also depicts a much more authentic form of mass communication in the ancient city: writing on walls.

This includes not only the formal and well-planned inscriptions shown on buildings and triumphal arches, but the informal scratchings, painted notices and charcoal messages scribbled on the walls of the city.

The hero of the first Gladiator film, Maximus (played by Russell Crowe in 2000), has his name crudely carved onto his makeshift secret tomb in the Colosseum. Elsewhere his name has been erased from a list of gladiatorial victors in a parody of damnatio memoriae, the process by which the name and image of a person was removed from public inscriptions and buildings.

This is rather like the way the real Emperor Geta (played by Joseph Quinn) had his name and image erased from Rome following his murder at the hands of his brother Caracalla (Fred Hechinger).

Latin-literate viewers may spot a particularly obscene threat to the emperors – “irrumabo imperatores” – painted on an external wall of Rome in the background of one scene. This most likely draws on Roman poet Catullus’s Poem 16, a work deemed so offensive that it wasn’t even translated into English until the 20th century.

While the language may seem gratuitous – it roughly translates as “I will orally fuck the emperors” – this is precisely the sort of vernacular that survives on the walls of Pompeii. Archaeologists have uncovered quotes from the poet Virgil, greetings to friends, price lists, practice alphabets, the scribbled drawings of children and the doodling of adults. Yet much of the graffiti would not look out of place on the back of a toilet door.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the walls of Pompeii’s brothel were a particular hot-spot for sexual graffiti.

One anonymous customer boasts that he had “fucked many girls there”, but similar comments are found on the walls of taverns, bathhouses and in the slightly shady area of tombs on the roads just outside of Pompeii.

Political protest

Yet there was also a serious side to ancient graffiti. The plot of the first Gladiator film centred on the memory of a democratic Rome that had once been a republic, in contrast to the oppression, cruelty and political intrigue of the city as ruled by Emperor Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix). The Rome of Gladiator II is similarly portrayed as one of political unrest. It’s ruled over by two tyrannical brothers, Geta and Caracalla, who are entirely ill-suited to leadership.

The trailer for Gladiator II.

In such circumstances, graffiti can be an important form of political expression and resistance. In Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), Romanes eunt domus daubed on a wall in Jerusalem, is famously parsed by John Cleese’s Roman soldier as “People called Romanes, they go, the house” and corrected to Romani ite domum or “Romans go home”.

This fictional scene may be the most famous example of political graffiti from the Roman world, but there are plenty of real-life instances from ancient literature. They indicate that graffiti was an established way for the people of Rome to communicate their displeasure about the actions of their leaders, writing on walls, columns and on placards hung around the necks of statues.

Brutus, for instance, was encouraged to join the conspiracy against Julius Caesar by graffiti written in Rome under the cover of darkness. When Emperor Tiberius’ stepson Germanicus died and Tiberius was suspected of having had him murdered, notices appeared on walls in Rome demanding, somewhat unfeasibly, Germanicus’ return.

In the latter years of Emperor Nero’s reign and at a time of high food prices when people must have found Nero’s theatrical excess particularly galling, mocking graffiti appeared around the city. Emperor Domitian apparently erected so many triumphal arches in the city that someone wrote “It is enough” in Greek on one of them.

People in Rome had every reason to feel aggrieved by the actions of Caracalla and Geta, both in the film and historically. The film versions of the emperors are portrayed as out-of-touch with reality, living a life of luxury and focusing only on the arena. Caracalla even makes his monkey a consul, an echo of Roman historian Suetonius’ famous claim that Emperor Caligula was planning to bestow the same honour on his horse.

The historian Cassius Dio paints a picture of the brothers abusing women and boys, embezzling money and hanging out with gladiators and charioteers in Rome. Later, Caracalla was ruthless in removing any potential threats to his power, including Geta and 20,000 of his followers as well as his own wife, Fulvia Plautilla.

The obscene graffiti directed against Caracalla and Geta in Gladiator II then is part of a long tradition of political resistance in Rome. The anonymous author undercuts the tyranny and pomp of the emperors by rendering them sexually passive – an insult to their masculinity in a Roman context – and slightly ridiculous.

Unlike the senator sitting outside the cafe with his newspaper, the daubing of “irrumabo imperatores” on a wall of Rome by cover of darkness is perfectly believable.

Claire Holleran, Associate Professor Classics and Ancient History, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In the latter years of Emperor Nero’s reign and at a time of high food prices when people must have found Nero’s theatrical excess particularly galling, mocking graffiti appeared around the city. Emperor Domitian apparently erected so many triumphal arches in the city that someone wrote “It is enough” in Greek on one of them.

People in Rome had every reason to feel aggrieved by the actions of Caracalla and Geta, both in the film and historically. The film versions of the emperors are portrayed as out-of-touch with reality, living a life of luxury and focusing only on the arena. Caracalla even makes his monkey a consul, an echo of Roman historian Suetonius’ famous claim that Emperor Caligula was planning to bestow the same honour on his horse.

The historian Cassius Dio paints a picture of the brothers abusing women and boys, embezzling money and hanging out with gladiators and charioteers in Rome. Later, Caracalla was ruthless in removing any potential threats to his power, including Geta and 20,000 of his followers as well as his own wife, Fulvia Plautilla.

The obscene graffiti directed against Caracalla and Geta in Gladiator II then is part of a long tradition of political resistance in Rome. The anonymous author undercuts the tyranny and pomp of the emperors by rendering them sexually passive – an insult to their masculinity in a Roman context – and slightly ridiculous.

Unlike the senator sitting outside the cafe with his newspaper, the daubing of “irrumabo imperatores” on a wall of Rome by cover of darkness is perfectly believable.

Claire Holleran, Associate Professor Classics and Ancient History, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To some ancient Romans, gladiators were the embodiment of tyranny

Photo by Leonhard Niederwimmer on Unsplash

a very old building with a lot of arches

Caricature as character

To participate in Roman political culture required training in rhetoric and oratory.

Although a good deal of oratorical training was done by modeling oneself after one’s teachers, the first century B.C.E. saw an influx of influential rhetorical teachers from Greece, and a boom in what might loosely be called textbooks of rhetoric. These manuals not only offer theoretical discussions of what makes a good speech, but they also reveal a great deal about Roman values.

Books like the anonymous “Rhetoric for Herennius,” which circulated in the earlier years of Cicero’s political career, teemed with examples for how to characterize the opposition in a court of law.

The author – as Cicero wrote in his own work, “On Rhetorical Brianstorming” – emphasized that discussions of physical attributes were not just fair game; they were all but expected as a way to highlight a plaintiff’s or defendant’s virtuous – or vicious – character.

Good looks, for instance, could be used favorably to show how nature’s blessings added to a client’s virtue without leading to pride. When characterized unfavorably, those same good looks might be spun as a product of the opponent’s vanity and self-indulgence.

More to the sword-point: According to the author of “Rhetoric for Herennius,” qualities of speed and strength might be highlighted to show “respectable training and effort” when done in moderation. But if you’re looking to tear down an opponent, the orator may “mention his use of [speed and strength], which any given gladiator may have thanks to dumb luck.”

Strength? Definitely.

Honor? Depends who you ask.

John M. Oksanish, Associate Professor of Classics, Wake Forest University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by Leonhard Niederwimmer on Unsplash

a very old building with a lot of arches

November 24, 2024

Neither “Gladiator” nor its cinematic sequel is particularly concerned with historical fact. For one thing, the emperor Marcus Aurelius had no intention of restoring the republic. Gladiatorial contests were abhorrent displays of cruelty, but they didn’t always end in death. And the Romans didn’t sculpt bone-white statues; they painted them using an array of colors.

But I’m most interested in how the two films misrepresent the way Roman gladiators and their bodies were viewed by their republic-minded contemporaries.

In the films, the brawny biceps of gladiators Maximus and Lucius reflect “strength and honor” – to reprise the motto of the franchise – as each of these heroes fights to overthrow self-indulgent emperors and to restore the Roman republic with its traditional political values of liberty and self-restraint.

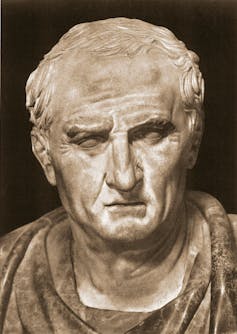

However, as I discuss in my book, “Vitruvian Man: Rome Under Construction,” the gladiator represented something else altogether. The most famous martyr of the Roman republic – Marcus Tullius Cicero – used gladiators’ physiques not to celebrate the republic’s valiant heroes, but to deride their bloated muscles as the embodiment of amoral tyranny.

Neither “Gladiator” nor its cinematic sequel is particularly concerned with historical fact. For one thing, the emperor Marcus Aurelius had no intention of restoring the republic. Gladiatorial contests were abhorrent displays of cruelty, but they didn’t always end in death. And the Romans didn’t sculpt bone-white statues; they painted them using an array of colors.

But I’m most interested in how the two films misrepresent the way Roman gladiators and their bodies were viewed by their republic-minded contemporaries.

In the films, the brawny biceps of gladiators Maximus and Lucius reflect “strength and honor” – to reprise the motto of the franchise – as each of these heroes fights to overthrow self-indulgent emperors and to restore the Roman republic with its traditional political values of liberty and self-restraint.

However, as I discuss in my book, “Vitruvian Man: Rome Under Construction,” the gladiator represented something else altogether. The most famous martyr of the Roman republic – Marcus Tullius Cicero – used gladiators’ physiques not to celebrate the republic’s valiant heroes, but to deride their bloated muscles as the embodiment of amoral tyranny.

Enemies of the Republic?

Cicero’s career was both marked and made by the constitutional crises that characterized the last decades of the Roman republic. In several of his speeches from the period, he characterized the enemies of the republic as gladiators.

In the so-called second Catilinarian conspiracy of 62 B.C.E., Lucius Sergius Catilina, also known as Catiline, attempted a coup after losing his campaign to become a consul. Rome’s highest office, a consul was the rough equivalent to a U.S. president, except he served for one year alongside another consul, with each wielding equal political power.

Cicero’s career was both marked and made by the constitutional crises that characterized the last decades of the Roman republic. In several of his speeches from the period, he characterized the enemies of the republic as gladiators.

In the so-called second Catilinarian conspiracy of 62 B.C.E., Lucius Sergius Catilina, also known as Catiline, attempted a coup after losing his campaign to become a consul. Rome’s highest office, a consul was the rough equivalent to a U.S. president, except he served for one year alongside another consul, with each wielding equal political power.

Cicero saw little to admire in a brawny body.

Stock Montage/Getty Images

Cicero, who was consul himself that year, pulled no punches in his speeches, which were all premised upon the notion that the would-be usurper Catiline – though of noble birth – was an enemy because he associated with “the criminals of the gladiatorial schools.”

The real defenders of Roman values – according to Cicero, anyway – exchanged sharp words in the Roman senate. Catiline, on the other hand, “trained” his superhuman physical hardiness to inflict “insult” and “wickedness” on the republic, its institutions and its freedoms, all while wielding a dagger, the weapon of thugs and cutthroats.

A couple of decades later, when the Roman republic had placed unprecedented political power in the hands of three men, Cicero again deployed the figure of the gladiator as a troubling symbol.

This time, he used it to call out one of these three “triumvirs,” Mark Antony, whose later alliance and dalliance with Cleopatra made him an enemy not only of the Roman republic, but also of Roman identity itself.

In his red-hot second Philippic – one of 14 invectives directed against Antony – Cicero put the spotlight on Antony’s rugged, gladiatorial body and its monstrous capacity for self-indulgence. This was a disgrace unfit for the Roman populace, and it was at odds with the traditional value of self-restraint in Roman political life:

“You! With your neck, your sides, your hard, gladiator’s body: you drained down enough wine at Hippia’s wedding that you had to throw it all up in plain sight of the Roman people the next day.”

But apart from the simple fact that most gladiators were enslaved – and, for that reason, were scorned by elites as social outcasts – there is another reason for the prevalence of this image in Roman political language.

Cicero, who was consul himself that year, pulled no punches in his speeches, which were all premised upon the notion that the would-be usurper Catiline – though of noble birth – was an enemy because he associated with “the criminals of the gladiatorial schools.”

The real defenders of Roman values – according to Cicero, anyway – exchanged sharp words in the Roman senate. Catiline, on the other hand, “trained” his superhuman physical hardiness to inflict “insult” and “wickedness” on the republic, its institutions and its freedoms, all while wielding a dagger, the weapon of thugs and cutthroats.

A couple of decades later, when the Roman republic had placed unprecedented political power in the hands of three men, Cicero again deployed the figure of the gladiator as a troubling symbol.

This time, he used it to call out one of these three “triumvirs,” Mark Antony, whose later alliance and dalliance with Cleopatra made him an enemy not only of the Roman republic, but also of Roman identity itself.

In his red-hot second Philippic – one of 14 invectives directed against Antony – Cicero put the spotlight on Antony’s rugged, gladiatorial body and its monstrous capacity for self-indulgence. This was a disgrace unfit for the Roman populace, and it was at odds with the traditional value of self-restraint in Roman political life:

“You! With your neck, your sides, your hard, gladiator’s body: you drained down enough wine at Hippia’s wedding that you had to throw it all up in plain sight of the Roman people the next day.”

But apart from the simple fact that most gladiators were enslaved – and, for that reason, were scorned by elites as social outcasts – there is another reason for the prevalence of this image in Roman political language.

Caricature as character

To participate in Roman political culture required training in rhetoric and oratory.

Although a good deal of oratorical training was done by modeling oneself after one’s teachers, the first century B.C.E. saw an influx of influential rhetorical teachers from Greece, and a boom in what might loosely be called textbooks of rhetoric. These manuals not only offer theoretical discussions of what makes a good speech, but they also reveal a great deal about Roman values.

Books like the anonymous “Rhetoric for Herennius,” which circulated in the earlier years of Cicero’s political career, teemed with examples for how to characterize the opposition in a court of law.

The author – as Cicero wrote in his own work, “On Rhetorical Brianstorming” – emphasized that discussions of physical attributes were not just fair game; they were all but expected as a way to highlight a plaintiff’s or defendant’s virtuous – or vicious – character.

Good looks, for instance, could be used favorably to show how nature’s blessings added to a client’s virtue without leading to pride. When characterized unfavorably, those same good looks might be spun as a product of the opponent’s vanity and self-indulgence.

More to the sword-point: According to the author of “Rhetoric for Herennius,” qualities of speed and strength might be highlighted to show “respectable training and effort” when done in moderation. But if you’re looking to tear down an opponent, the orator may “mention his use of [speed and strength], which any given gladiator may have thanks to dumb luck.”

Strength? Definitely.

Honor? Depends who you ask.

John M. Oksanish, Associate Professor of Classics, Wake Forest University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.