THE WAR ON THE WAR ON CANCER

Trump’s Gutting of Toxics Regulations Will Mean Higher Profits for Polluters and Higher Cancer Rates for the American People

FEATURE ARTICLE LONG READ

A Polluter’s Paradise

There may be no better place to see the consequences of the unraveling of chemical regulation than in Texas. Home to roughly two-thirds of the nation’s petrochemical industry and a fast-growing number of factories that make plastic and its feedstocks, Texas is a hub for the production of carcinogenic compounds as well as a leader in the movement to weaken regulations of them. For years, Texas has been a polluter’s paradise. As the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries have exploded throughout the state, the TCEQ’s Honeycutt has presided over an easing of restrictions on their emissions even as his staff has been reduced.

With 1.7 million new cases estimated for 2019 in the United States, cancer is a particular problem in Freeport, Texas. Rates of Hodgkin lymphoma are elevated in this small town on the Gulf Coast, as are cancers of the liver and bile duct, lung, stomach, and nasal cavity and middle ear, according to a report that the Texas Department of State Health Services quietly released in 2018.

The report makes no mention of pollution as a possible cause of the elevated number of cancer cases, yet Freeport is home to the largest chemical production facility in the western hemisphere: 12,800 acres of holding tanks, machinery, canals, deep-water ports, and pipelines, owned by Dow. Alongside it are chemical production facilities owned by other companies, including BASF, Shintech, Huntsman, and the Olin Corporation, the largest chlor-alkali producer in the world, which bought part of its Freeport manufacturing site from Dow in 2015.

Dow’s Freeport plant produces more than 40 billion pounds of chemicals and other products, including the components of much of the world’s plastics. In the process, the plant emits hundreds of toxic chemicals. The facility released more than 200 air pollutants in 2017 and has violated its permits in every quarter of the past three years, making it a high-priority violator of the Clean Air Act. Between 2015 and 2018, the complex emitted more than 3 million pounds of unpermitted air pollution on top of what it was allowed to release, according to a report by the Environmental Integrity Project.

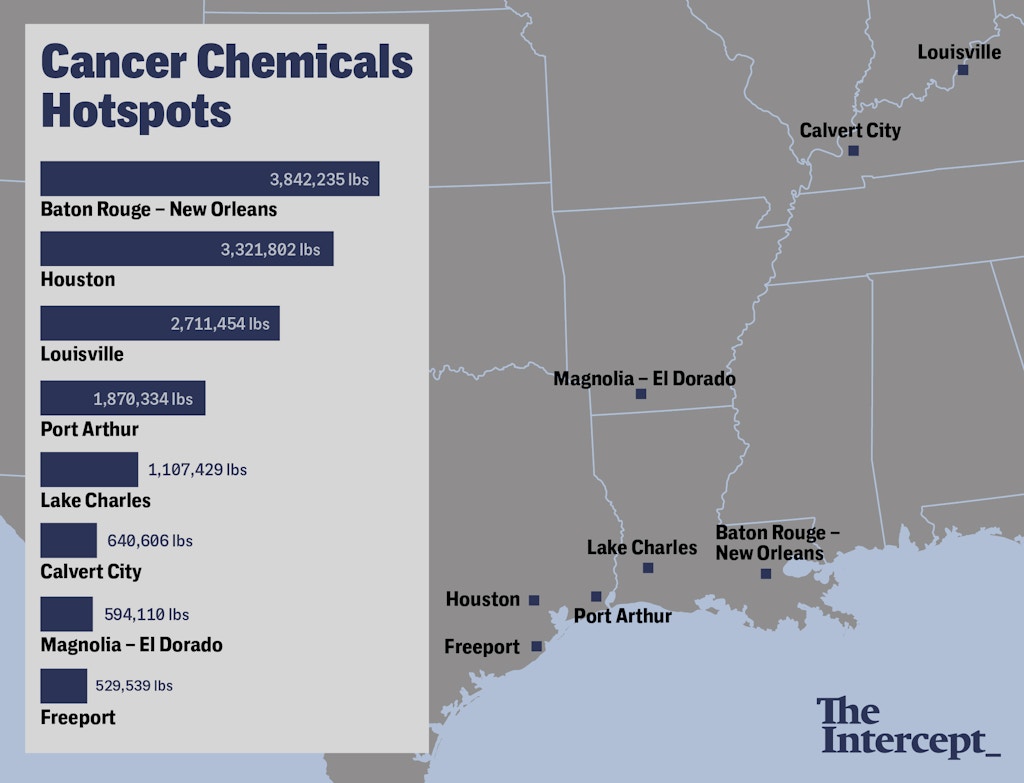

On-site manufacturing releases of 18 of the 19 carcinogens currently being reviewed by the EPA under the revised 2016 Toxic Substances Control Act. All data drawn from the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, 2014 – 2018, as reported by manufacturers. Locations include facilities within 50 miles. Data does not include releases at waste disposal/recycling facilities or on-site underground injection wells.

Graphic: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

Among the pollutants being released by Dow in Freeport are 11 carcinogens that are now being assessed or considered for assessment by the EPA under the new toxic chemicals law, according to EPA data. Of those chemicals, five have been shown to increase levels of the very cancers that are elevated in Freeport. Over the past five years, the Dow plant released more than 221,000 pounds of these five chemicals, including 1,2-dichloropropane, which causes bile duct cancer and is a probable cause of cancer of the nasal cavity and inner ear; 1,3-butadiene, which has been shown to increase rates of stomach cancers (and was recently released in an explosion at another chemical plant on the Texas coast); 1,1,2-trichloroethane and 1,1-dichloroethane, both of which have been linked to liver cancer in mice; and 1,2-dichloroethane, a probable carcinogen that has been linked to stomach, liver, and lung cancers.

But initial reports that the EPA recently released on the chemicals it’s investigating omit information that the agency has in its own databases about where and in what quantities these chemicals are produced, which companies make them, and how they’re used. As a result, most people in Freeport — and other polluted communities — do not realize that the industrial facilities near them are releasing dangerous amounts of these carcinogens. Also, because they omit this critical information, the assessments themselves may not reflect the true dangers posed by these substances.

Dow has done little to address the prevalence of cancer in the area, though the company did sponsor a “Sparkles and Spurs” fundraiser in 2018 to help buy a CT scanner for the CHI St. Luke’s Health cancer center in Brazosport, Texas, which is just a 15-minute drive from the Dow Chemical plant. Some residents call it the “Dow Cancer Center” because it was built on land donated by the giant chemical company. The evening of food, fun, and “foot stompin’” country music helped the center purchase the CT scanner, which the hospital is still using to diagnose new cancer cases.

Although they are more likely to get certain cancers, residents of Freeport — where the median household income is less than $37,000 a year — may have a difficult time getting care at the local hospital. “The Dow cancer center won’t take indigent patients,” said Melanie Oldham, a Freeport resident and physical therapist who said that she has worked with hundreds of clients in the area who have had cancer. “People who don’t have good insurance end up having to drive back and forth to either Galveston or to MD Anderson, which is an hour away.” Many of them are workers at the Dow plant, according to Oldham. “These are great jobs until you’re 50 or so,” she said. “That’s when a lot of my patients develop cancer.”

No comments:

Post a Comment