This overarching history of the Brigades who fought in the Spanish civil war is a remarkable collection of testimonies and captivatingly readable

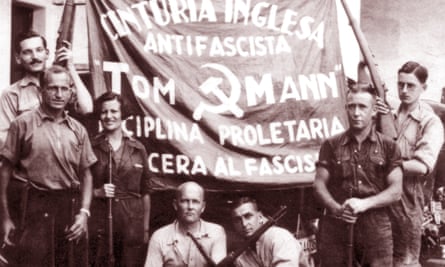

British volunteers in the International Brigade, 1937. Photograph: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Dan Hancox

Sat 3 Oct 2020

“We shall not forget you,” promised the famous Spanish communist known as La Pasionaria, addressing the surviving International Brigades as they departed Barcelona in October 1938, with Franco’s victory in the Spanish civil war nearly complete: “And when the olive tree of peace is in flower … return!” In mid-September 2020, the Spanish cabinet made a remarkable gesture in the same spirit: approving a draft of a new “democratic memory” law, which would offer citizenship to the descendants of those same volunteers. “It is about time we said to these heroes and heroines of democracy: thank you for coming,” Deputy PM Pablo Iglesias wrote.

A government spokesperson later rowed back on this highly unusual idea, but its spirit speaks to a unique moment in 20th-century history, where the engine of political change was in overdrive across Europe, to the point that volunteers travelled in their thousands to fight fascism and defend democracy in a foreign land, in the face of their own government’s indifference. There exist few parallels either before or since, although the journey of some volunteers to help the Kurds fighting Islamic State is one notable exception. For the late academic and writer David Graeber, whose father volunteered to fight fascism in Spain, the resonance was especially painful; he argued in the Guardian that the west’s abandonment of the struggle in Rojava, Syria, was tantamount to letting history repeat itself.

The Spanish civil war has long been valorised by the European left, documented, debated and commemorated in incredible detail – in many thousands of books, but also in film, in song, in musical theatre, in poster exhibitions, badges and T-shirts. And while there are many tales of selfless sacrifice, solidarity and idealism, there is also much in the story that is inglorious – the boredom, unpreparedness and terrible equipment, the panic, internal arguments and betrayals, lice, accidental deaths and injuries and Franco’s eventual triumph.

Sculpture of ‘La Pasionaria’ in Glasgow, Photograph: Peter Marshall/Alamy

Imposing order on a history that is both chaotic and contentious can be tricky, but like the volunteer army itself, Giles Tremlett’s epic new book is greater than the sum of its many parts. It comprises 52 time-specific chapters, discrete moments, battles, battalions and tales, building into a narrative of astonishing scope. Tremlett is known for his reporting and several books, among them the excellent Ghosts of Spain, which looks at the shadows cast by the “memory wars” in a country otherwise riding high, pre-financial crash. This latest study is a remarkable act of scholarship, as well as being captivatingly readable. The first overarching history of the brigades in English, it is alive with the testimonies of those who fought, and so much richer for stretching far beyond the obvious and famous Anglophone accounts of men of letters.

It is true the brigades drew an astonishing array of international literary figures – Orwell, Hemingway, Spender, Auden – and also great photographers, artists, and politicians in the making. But above all, it attracted working-class men and women from across Europe and beyond: many of them already refugees, those fleeing or fearing persecution, unemployment and degradation. There were French, Poles, Germans and Italians in their thousands, but also brigaders from Ethiopia, Argentina, Indonesia, Japan and Pakistan. A good half of those who volunteered were communists, and they did so alongside socialists, anarchists, liberals, democrats, people of all faiths and none, even a few conservatives and politically agnostic adventurers, from 65 countries, with only one thing uniting them: anti-fascism. Remarkable individual lives fly past in a single tantalising line: the three Jewish tailors from Stepney who had “arrived by bicycle”, for example.

In one of many unforgettable vignettes, a trainload of new volunteers from “all the nations in Europe, and some from outside Europe as well” crossing the border into Spain with no common language, join together to sing the “Internationale”, but each doing so in their own tongue. “I find it extremely difficult to explain how exhilarating this was,” recalls a British volunteer. “I don’t think I’ve ever felt the same feeling at any other time in my life.”

Dan Hancox

Sat 3 Oct 2020

“We shall not forget you,” promised the famous Spanish communist known as La Pasionaria, addressing the surviving International Brigades as they departed Barcelona in October 1938, with Franco’s victory in the Spanish civil war nearly complete: “And when the olive tree of peace is in flower … return!” In mid-September 2020, the Spanish cabinet made a remarkable gesture in the same spirit: approving a draft of a new “democratic memory” law, which would offer citizenship to the descendants of those same volunteers. “It is about time we said to these heroes and heroines of democracy: thank you for coming,” Deputy PM Pablo Iglesias wrote.

A government spokesperson later rowed back on this highly unusual idea, but its spirit speaks to a unique moment in 20th-century history, where the engine of political change was in overdrive across Europe, to the point that volunteers travelled in their thousands to fight fascism and defend democracy in a foreign land, in the face of their own government’s indifference. There exist few parallels either before or since, although the journey of some volunteers to help the Kurds fighting Islamic State is one notable exception. For the late academic and writer David Graeber, whose father volunteered to fight fascism in Spain, the resonance was especially painful; he argued in the Guardian that the west’s abandonment of the struggle in Rojava, Syria, was tantamount to letting history repeat itself.

The Spanish civil war has long been valorised by the European left, documented, debated and commemorated in incredible detail – in many thousands of books, but also in film, in song, in musical theatre, in poster exhibitions, badges and T-shirts. And while there are many tales of selfless sacrifice, solidarity and idealism, there is also much in the story that is inglorious – the boredom, unpreparedness and terrible equipment, the panic, internal arguments and betrayals, lice, accidental deaths and injuries and Franco’s eventual triumph.

Sculpture of ‘La Pasionaria’ in Glasgow, Photograph: Peter Marshall/Alamy

Imposing order on a history that is both chaotic and contentious can be tricky, but like the volunteer army itself, Giles Tremlett’s epic new book is greater than the sum of its many parts. It comprises 52 time-specific chapters, discrete moments, battles, battalions and tales, building into a narrative of astonishing scope. Tremlett is known for his reporting and several books, among them the excellent Ghosts of Spain, which looks at the shadows cast by the “memory wars” in a country otherwise riding high, pre-financial crash. This latest study is a remarkable act of scholarship, as well as being captivatingly readable. The first overarching history of the brigades in English, it is alive with the testimonies of those who fought, and so much richer for stretching far beyond the obvious and famous Anglophone accounts of men of letters.

It is true the brigades drew an astonishing array of international literary figures – Orwell, Hemingway, Spender, Auden – and also great photographers, artists, and politicians in the making. But above all, it attracted working-class men and women from across Europe and beyond: many of them already refugees, those fleeing or fearing persecution, unemployment and degradation. There were French, Poles, Germans and Italians in their thousands, but also brigaders from Ethiopia, Argentina, Indonesia, Japan and Pakistan. A good half of those who volunteered were communists, and they did so alongside socialists, anarchists, liberals, democrats, people of all faiths and none, even a few conservatives and politically agnostic adventurers, from 65 countries, with only one thing uniting them: anti-fascism. Remarkable individual lives fly past in a single tantalising line: the three Jewish tailors from Stepney who had “arrived by bicycle”, for example.

In one of many unforgettable vignettes, a trainload of new volunteers from “all the nations in Europe, and some from outside Europe as well” crossing the border into Spain with no common language, join together to sing the “Internationale”, but each doing so in their own tongue. “I find it extremely difficult to explain how exhilarating this was,” recalls a British volunteer. “I don’t think I’ve ever felt the same feeling at any other time in my life.”

Photograph: Photo 12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

For too long the volunteers were fighting an amateur war in defence of the republic; they were a ragtag collection of militias in mismatched uniforms, who looked, in the words of artist Felicia Browne, “like pirates”. In October 1936, when the first official brigade departed from a base in Albacete for the front, the British writer John Sommerfield recalled that their uniforms and equipment had arrived that very afternoon. “Everyone got something and no one got everything. We marched off looking like a lot of scarecrows, and in filthy tempers.”

Bad weapons, lack of training, the urgency of the conflict and, in the minds of some brigaders, “absurd democratisation” weakened discipline in the ranks. Tremlett records the distrust and tensions, especially in the anarchist and Poum ranks, over the Soviet Union’s semi-professionalisation of the initial anti-fascist militias: “Discipline was something that the fascist army in front of them used to oppress its working-class soldiers,” Tremlett writes. These were internal suspicions that would last almost throughout the three-year conflict.

As recounted in one horrifying chapter, the Sans Nom, or “nameless” battalion of Poles, Serbs and other miscellaneous non-French volunteers, went to the southern front in Andalusia after just five days of training, having fired only six practice shots each, with only four of their 36 machine guns working. They were sent into battle on Christmas Eve without maps, mostly on foot, right into a Francoist assault. Abandoned by their commander to the fascists’ Moroccan cavalry, they fled chaotically – rather than beating an organised retreat – across the substantial Guadalquivir river, where some drowned, and others were picked off with ease on the other side. On Christmas Day, unarmed groups and individuals wandered the olive groves, lost, clothes in tatters, eating bitter olives and grass for sustenance; only half of the 700 Sans Nom volunteers made it back alive.

Betrayal is a thread that runs throughout the Spanish tragedy. The brigades were often let down by their Soviet and Spanish commanders, but also by their own governments, who left both their lives and that of Spanish democracy to the fate of the aerial assault of Hitler and Mussolini. On returning to their own countries – those who did make it home; one-fifth of British volunteers died in Spain – many were treated as dangerous dissidents, spied on and prevented from fighting fascism in the second world war. But they were not abandoned by the establishment in its entirety: it is notable that both Clement Attlee and the anti-appeasement Edward Heath were among the crowd at Victoria Station to welcome home the returning British volunteers.

For too long the volunteers were fighting an amateur war in defence of the republic; they were a ragtag collection of militias in mismatched uniforms, who looked, in the words of artist Felicia Browne, “like pirates”. In October 1936, when the first official brigade departed from a base in Albacete for the front, the British writer John Sommerfield recalled that their uniforms and equipment had arrived that very afternoon. “Everyone got something and no one got everything. We marched off looking like a lot of scarecrows, and in filthy tempers.”

Bad weapons, lack of training, the urgency of the conflict and, in the minds of some brigaders, “absurd democratisation” weakened discipline in the ranks. Tremlett records the distrust and tensions, especially in the anarchist and Poum ranks, over the Soviet Union’s semi-professionalisation of the initial anti-fascist militias: “Discipline was something that the fascist army in front of them used to oppress its working-class soldiers,” Tremlett writes. These were internal suspicions that would last almost throughout the three-year conflict.

As recounted in one horrifying chapter, the Sans Nom, or “nameless” battalion of Poles, Serbs and other miscellaneous non-French volunteers, went to the southern front in Andalusia after just five days of training, having fired only six practice shots each, with only four of their 36 machine guns working. They were sent into battle on Christmas Eve without maps, mostly on foot, right into a Francoist assault. Abandoned by their commander to the fascists’ Moroccan cavalry, they fled chaotically – rather than beating an organised retreat – across the substantial Guadalquivir river, where some drowned, and others were picked off with ease on the other side. On Christmas Day, unarmed groups and individuals wandered the olive groves, lost, clothes in tatters, eating bitter olives and grass for sustenance; only half of the 700 Sans Nom volunteers made it back alive.

Betrayal is a thread that runs throughout the Spanish tragedy. The brigades were often let down by their Soviet and Spanish commanders, but also by their own governments, who left both their lives and that of Spanish democracy to the fate of the aerial assault of Hitler and Mussolini. On returning to their own countries – those who did make it home; one-fifth of British volunteers died in Spain – many were treated as dangerous dissidents, spied on and prevented from fighting fascism in the second world war. But they were not abandoned by the establishment in its entirety: it is notable that both Clement Attlee and the anti-appeasement Edward Heath were among the crowd at Victoria Station to welcome home the returning British volunteers.

A memorial to anti-fascist dead in Valladolid. Photograph: Juan Medina/Reuters

The International Brigades arrives at a critical point in more ways than one. It would be useful for some contemporary pundits and politicians to be reminded that “horseshoe theory”, which places anti-fascist activity in the same category as the fascists they oppose, is dangerous nonsense. But it is also a critical point for the legacy of the brigaders: the last British veteran, Geoffrey Servante, died last year at the age of 99; there are at most a couple of other survivors left in the world.

Fortunately, Tremlett is a worthy custodian of their stories. He has created a dazzling mosaic of vignettes and sources, of lives lived and lost, of acts of heroism, solidarity, betrayal and futility, that builds to a grand picture of a conflict that drew idealists from across the world. The war left many of them in despair, injured or dead – but also hardened many more in their determination to defeat fascism. This book is as close to a definitive history as we are likely to get.

• The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War is published by Bloomsbury (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

1400 CANADIANS FOUGHT WITH THE INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES

The Spanish civil war: a primer

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/LYN442LIYVH25DESH3BFWPE3UY)

Jules Paivio, right, is the last surviving veteran of the Mackenzie-Papineau Batallion. This photo shows him with two other briadistas, Briton Frank Graham and American Harold Smith, during the Spanish Civil War.

The International Brigades arrives at a critical point in more ways than one. It would be useful for some contemporary pundits and politicians to be reminded that “horseshoe theory”, which places anti-fascist activity in the same category as the fascists they oppose, is dangerous nonsense. But it is also a critical point for the legacy of the brigaders: the last British veteran, Geoffrey Servante, died last year at the age of 99; there are at most a couple of other survivors left in the world.

Fortunately, Tremlett is a worthy custodian of their stories. He has created a dazzling mosaic of vignettes and sources, of lives lived and lost, of acts of heroism, solidarity, betrayal and futility, that builds to a grand picture of a conflict that drew idealists from across the world. The war left many of them in despair, injured or dead – but also hardened many more in their determination to defeat fascism. This book is as close to a definitive history as we are likely to get.

• The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War is published by Bloomsbury (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

1400 CANADIANS FOUGHT WITH THE INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES

The Spanish civil war: a primer

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/LYN442LIYVH25DESH3BFWPE3UY)

Jules Paivio, right, is the last surviving veteran of the Mackenzie-Papineau Batallion. This photo shows him with two other briadistas, Briton Frank Graham and American Harold Smith, during the Spanish Civil War.

KATE TAYLOR

Spanish Civil War: Deep divisions in Spanish society between the army, church and monarchists, and the democratically elected reformist Republican government supported by democrats, anarchists, socialists and communists led to a military coup in 1936. Russia and Mexico supported the Republicans; Italy, Germany and Portugal supported the Nationalists. The bloody conflict that ensued ended with the Nationalists' victory in 1939 and the collapse of the government: General Francisco Franco took power in a military dictatorship that lasted until his death in 1975, after which King Juan Carlos established a constitutional monarchy.

International Brigades: In the absence of armed support for Spain from the Western powers, the Communist International headquartered in Paris organized a volunteer army, with Soviet approval. About 60,000 men and women from more than 50 countries, including France, Italy, Germany, Britain, Canada and the United States, volunteered for combat and non-combat roles. They were soldiers, nurses, doctors (includijng Norman Bethune) and journalists (such as George Orwell). At any given point in the war, it was estimated that 20,000 volunteers were fighting. The brigades were discharged by the Spanish government in 1938, shortly before it fell. In recent years, Spain has awarded honorary citizenship to the remaining brigadistas.

The Mackenzie-Papineau Batallion: In 1937, Canadian volunteers, who first fought in the two American battalions, formed their own unit and fought in Spain until 1938. They took their name from William Lyon Mackenzie and Louis-Joseph Papineau, two heroes of the 1837 Rebellion. Library and Archives Canada records the names of 1,546 Canadians who fought in Spain, and estimates that about 400 of them were killed, although some researchers put the death toll higher. Because of the brigades' association with communism, the veterans had difficulty getting recognition at home, even as thousands more Canadians were soon fighting fascism in Europe during the Second World War. A monument to their memory was finally erected in Ottawa in 2001.

RADIO

The Mac-Paps get the last word

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/IPPNMLR7CVAE7FFXU5IAGURDCY)

Spain; 1937-1938--Spanish Civil War-- Soldier of the Mackenzie-Papineau Batallion in a trench.

(CP PHOTO) 1999 (NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF CANADA)

KATE TAYLOR

PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 9, 2012

At the click of a mouse, a frail and cracked old voice fills the office of a CBC radio producer. "I have been a very lucky guy … I was lined up to be shot," says 95-year-old veteran Jules Paivio as he recalls his last-minute escape from a fascist firing squad during the Spanish Civil War.

CBC producer Steve Wadhams is also lucky: To create The Spanish Crucible, a two-hour radio documentary filled with the voices of veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, he didn't have to rely solely on his recent interview with Paivio, the last living Canadian volunteer to have fought in Spain in 1936 to 1938. Instead, he could draw on 150 hours of interviews with dozens of hearty middle-aged men that were recorded in the 1960s, but never aired.

"Forty-plus years of doing radio, and I have never stumbled into a treasure trove like this," Wadhams said.

The producer of Living Out Loud, a weekly program on CBC Radio One devoted to oral stories submitted by the public, Wadhams read about Paivio in a newspaper when the veteran was honoured with Spanish citizenship earlier this year. He asked CBC archivist Ken Puley to hunt for any interviews that might be on file. Puley found there was a 90-minute one with Paivio as well as "a few more." Puley handed over a stack of written summaries and "my jaw hit my chest," Wadhams said.

Puley had discovered the tapes from an oral history project conducted by CBC producer Mac Reynolds in 1964-65. Reynolds interviewed about 60 of the Mac-Paps, as the soldiers were known, a group of about 1,600 Canadian volunteers who, out of political conviction hardened by the Great Depression, went to the rescue of Spain's Republican government when it was under attack from the Spanish army lead by General Francisco Franco. Reynolds had recorded the stories of the often poor or unemployed Canadians who went to Europe to form an ill-equipped, amateur army fighting a bloody and ultimately unsuccessful battle against professionals backed by fascist governments in Italy and Germany.

"They were mainly working-class guys, a lot of them recent immigrants to Canada, 10-year immigrants. Loggers, miners, restaurant workers, out of work, in the relief camps. Some intellectuals, a university student, an accountant, a nurse, the only woman I've got," Wadhams said, referring to the interview with Rosaleen Ross, who worked on the mobile blood-transfusion team established by Canadian doctor Norman Bethune during his time in Spain. The volunteers were leaving the Depression behind, Wadhams said: "They were riding the rails, having a hard time in Canada, and they were politicized. Some were from Europe and saw what was happening."

The democratically elected reformist Republican government in Spain faced a military revolt, igniting the civil war, and anti-fascist volunteers were recruited abroad and sent to Spain. After the Canadian government passed a law in 1937 banning citizens from fighting in foreign wars, only the Communist Party was willing to flout the law and continue recruiting. Many of the volunteers were themselves Communists or at least sympathizers: The recruiters tried to weed out men who were seeking adventure or looking to escape a family.

Their politics and their decision to support a foreign government before Canada had entered the Second World War to join the battle against fascism in Europe were often held against them when they returned home. Discharged honourably by the Spanish government in 1938, shortly before its collapse in 1939, the Mac-Paps were regarded with suspicion by the RCMP, sometimes had trouble volunteering for the Canadian armed forces and were not recognized with their own monument in Ottawa until 2001.

Those politics may also explain why the CBC didn't use the tapes earlier: Wadhams speculates that during the Cold War years, the public broadcaster wasn't comfortable with, or at least not interested in, a project that might lionize the Mac-Paps. Reynolds is dead, but his daughter has told Wadhams that he was a Communist sympathizer, and may have regretted not going to Spain himself.

Wadhams says many documentaries about the International Brigades are clearly on the side of the boys, but he is trying to tell the story of these ill-paid and idealistic mercenaries more neutrally.

The details themselves are harrowing. The interviews include Paivio's description of climbing the snow-covered Pyrenees in dress shoes as the volunteers snuck into Spain from France. Others in a group that sailed to Barcelona narrowly escaped drowning when their ship was torpoed by an Italian submarine. They had arms supplied by the Russians – they often complained about their quality – and had to dig trenches in hard Spanish soil with helmets and spoons because they had no shovels. Their ranks were decimated in battles with the Nationalist army; more than a quarter of the battalion did not make it home.

If caught, they were treated to summary justice. But at the moment when Paivio and his comrades were about to be shot, an officer pulled them out of the firing line, perhaps recognizing that foreign nationals might prove useful hostages. When the war ended with the fascist victory, the foreigners were expelled while Spanish Republicans were relentlessly pursued by the regime that lasted until Franco died and democracy was restored in the 1970s.

"I'm lost in wonder," Wadham says of their experiences. "I can't imagine doing this, but they did … I feel an honour putting this on the radio, a responsibility. It's now or never."

In February 1965, almost 30 years after he set out for Spain, Paivio told a CBC interviewer: "The main thing was a terrible fear of fascism taking over. I didn't expect to come back … but it seemed a worthwhile thing."

No comments:

Post a Comment