By VIRGINIA TECH DECEMBER 11, 2020

A high flying Pteranodon, a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles. Illustration courtesy of Elenarts / Adobe Stock. Credit: Elenarts

Here’s the original story of flight. Sorry, Wright Brothers, but this story began way before your time — during the Age of the Dinosaurs.

Pterosaurs were the earliest reptiles to evolve powered flight, dominating the skies for 150 million years before their imminent extinction some 66 million years ago.

However, key details of their evolutionary origin and how they gained their ability to fly have remained a mystery; one that paleontologists have been trying to crack for the past 200 years. In order to learn more about their evolution and fill in a few gaps in the fossil record, their closest relatives had to be identified.

With the help of newly discovered skulls and skeletons that were unearthed in North America, Brazil, Argentina, and Madagascar in recent years, Virginia Tech researchers Sterling Nesbitt and Michelle Stocker from the Department of Geosciences in the College of Science have demonstrated that a group of “dinosaur precursors,” called lagerpetids, are the closest relatives of pterosaurs.

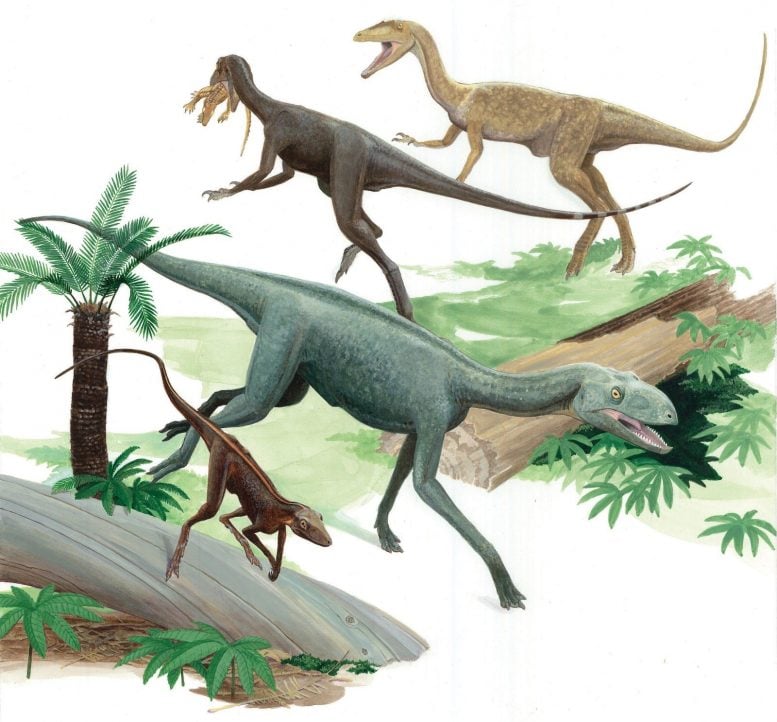

Artistic rendering of Dromomeron (foreground) and associated dinosaurs and relatives, based off of fossils from Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. Illustration courtesy of Donna Braginetz. Credit: Donna Braginetz

“Where did pterosaurs come from?’ is one of the most outstanding questions in reptile evolution; we think we now have an answer,” said Nesbitt, who is an associate professor of geosciences and an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute and the Global Change Center.

Their findings were published in Nature.

Fossils of Dromomeron gregorii, a species of lagerpetid, were first collected in Texas in the 1930s and 1940s, but they weren’t properly identified until 2009. Unique to this excavation was a well-preserved partial skull and braincase, which, after further investigation, revealed that these reptiles had a good sense of equilibrium and were likely agile animals.

A partial skeleton of Lagerpeton (hips, leg, and vertebrae) from ~235 million years from Argentina. Further examination of this specimen helped tie features of lagerpetids to pterosaurs. Photo courtesy of Sterling Nesbitt. Credit: Virginia Tech

After finding more lagerpetid species in South America, paleontologists were able to create a pretty good picture of what the lagerpetids were; which were small, wingless reptiles that lived across Pangea during much of the Triassic Period, from 237 to 210 million years ago.

And in the past 15 years, five research groups from six different countries and three continents have come together to right some wrongs in the evolutionary history of the pterosaur, after the recent discovery of many lagerpetid skulls, forelimbs, and vertebrae from the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Madagascar.

What gave paleontologists the idea to take a closer look at lagerpetids as the closest relatives of pterosaurs? Paleontologists have been studying the bones of lagerpetids for quite some time, and they have noted that the length and shape of their bones were similar to the bones of pterosaurs and dinosaurs. But with the few fossils that they had before, it could only be assumed that lagerpetids were a bit closer to dinosaurs.

What really caused a shift in the family tree can be attributed to the recently collected lagerpetid skulls and forelimbs, which displayed features that were more similar to pterosaurs than dinosaurs. And with the help of new technological advances, researchers found that pterosaurs and lagerpetids share far more similarities than meet the eye.

Using micro-computed tomographic (µCT) scanning to reconstruct their brains and sensory systems within the recently discovered skulls, paleontologists determined that the brains and sensory systems of lagerpetids had many similarities with those of pterosaurs.

“CT data has been revolutionary for paleontology,” said Stocker, who is an assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology and an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute and the Global Change Center.

“Some of these delicate fossils were collected nearly 80 years ago, and rather than destructively cutting into this first known skull of Dromomeron, we were able to use this technology to carefully reconstruct the brain and inner ear anatomy of these small fossils to help determine the early relatives of pterosaurs.”

One stark and mystifying finding was that the flightless lagerpetids had already evolved some of the neuroanatomical features that allowed the pterosaurs to fly, which brought forth even more information on the origin of flight.

“This study is a result of an international effort applying both traditional and cutting-edge techniques,” said Martín D. Ezcurra, lead author of the study from the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales in Buenos Aires, Argentina. “This is an example of how modern science and collaboration can shed light on long-standing questions that haunted paleontologists during more than a century.”

Ultimately, the study will help bridge the anatomical and evolutionary gaps that exist between pterosaurs and other reptiles. The new evolutionary relationships that have emerged from this study will create a new paradigm, providing a completely new framework for the study of the origin of these reptiles and their flight capabilities.

With the little information that paleontologists had about early pterosaurs, they had often attributed extremely fast evolution for the acquisition of their unique body plan. But now that lagerpetids are deemed the precursors of pterosaurs, paleontologists can say that pterosaurs evolved at the same rate as other major reptile groups, thanks to the newly discovered “middle man.”

“Flight is such a fascinating behaviour, and it evolved multiple times during Earth’s history,” said Serjoscha W. Evers, of the University of Fribourg. “Proposing a new hypothesis of their relationships with other extinct animals is a major step forward in understanding the origins of pterosaur flight.”

Some questions still remain in this evolutionary mystery. Now that lagerpetids are the closest relatives of pterosaurs, why are they still lacking some of the key characteristics of pterosaurs, including the most outstanding of those – wings?

“We are still missing lots of information about the earliest pterosaurs, and we still don’t know how their skeletons transformed into an animal that was capable of flight,” said Nesbitt.

Nesbitt, Stocker, and a team of Virginia Tech graduate and undergraduate students will continue to study animals that appeared in the Triassic Period – a period of time in Earth history when many familiar groups of vertebrates, such as dinosaurs, turtles, mammal relatives, and amphibians, first appeared. If and when conditions are safe, they plan on going into the field to collect more fossils from the Triassic Period.

Maybe soon, we will have more information to put some finishing touches on the original story of flight.

Reference: “Enigmatic dinosaur precursors bridge the gap to the origin of Pterosauria” by Martín D. Ezcurra, Sterling J. Nesbitt, Mario Bronzati, Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia, Federico L. Agnolin, Roger B. J. Benson, Federico Brissón Egli, Sergio F. Cabreira, Serjoscha W. Evers, Adriel R. Gentil, Randall B. Irmis, Agustín G. Martinelli, Fernando E. Novas, Lúcio Roberto da Silva, Nathan D. Smith, Michelle R. Stocker, Alan H. Turner and Max C. Langer, 9 December 2020, Nature.

No comments:

Post a Comment