Mongolia’s pitiless dzud

A herder collects snow to be melted down into drinking water.

By Anand Tumurtogoo in Ulaanbaatar February 20, 2021

The dzud is a peculiar weather phenomenon unique to Mongolia in which every few years a summer drought combines with a harsh winter. Nomadic herders can only despair as piles of dead, frozen sheep and goats stack up across the steppes, dead from either starvation or the cold. It is not uncommon to see a frozen animal dead on its feet.

Following the dry summer of 2020, most herders, mainly in the central provinces, were not able to prepare hay in the autumn because of degraded grazing lands. Thus, many were forced to buy fodder at high prices. This was a heavy blow to a great number of herders, particularly those who, given the disruption caused to trading by the coronavirus crisis, were unable to sell their primary source of income, cashmere wool.

Bones litter ground in Azraga Bag, Central Mongolia, the remnants of a dzud (Image: Taylor Weidman, The Vanishing Cultures Project, CC.Attrib.SA.3.0).

As of February 17, food and agriculture ministry data showed 402,300 livestock had died nationwide in Mongolia from the 2020/2021 dzud (sometimes spelt zud). The figures broke down to a list of devastation that included 2,100 camels, 17,200 horses, 36,600 cows, 123,300 sheep and 222,900 goats. In all, the dead animals were equivalent to 0.6% of the country’s livestock.

The highest number of livestock deaths were in the central regions, mainly in Arkhangai province (26,200 animals), Bayankhongor province (196,200), Gobi-Altai province (30,500), Uvurkhangai province (31,400) and Tuv province (35,600).

These numbers, however, are relatively low when held up against the more than 8mn livestock that perished in the dzud of 2010 or the more than 12mn lost from 1999 to 2001, infamous years that brought the worst dzud period in Mongolia’s history.

Towards 40% of Mongolia’s nomad population depend on animal husbandry for their livelihood.

In 2006, a UN research paper on Assessments of Impacts and Adaptations to Climate Change (AIACC) noted the following in describing the three-year dzud: “More than 12,000 herders’ families lost all their animals, while thousands of families had to subsist below the poverty line. Some people who lost all their animals even committed suicide.

“Such a long-lasting (three consecutive years) winter dzud followed by summer drought had not occurred in Mongolia in the last 60 years. Mongolia’s gross agricultural output in 2003 decreased by 40% compared to that in 1999 and its contribution to the national gross domestic product (GDP) decreased from 38% to 20% (Mongolian Statistical Yearbook, 2003). The livestock sector has become more destitute.”

Accursed year

As Mongolia’s latest winter loomed closer, the signs of it fast becoming severe were unmistakable. Herders in the central regions realised they had no time to lose in moving their livestock to the northern regions for more natural shelter and better grazing, but the accursed year of 2020 wasn't about to make things easy. Herders found their movements constrained as the nation went into a lockdown in November after officials recorded the first domestic transmissions of the coronavirus.

"Khurjun", or blocks of sheep and goat dung, protect animals during the dzud winter of 2010 in South Gobi (Image: Brucke-Osteuropa, public domain).

However, December brought a little good fortune: the virus was from that month seen as contained within the capital city, Ulaanbaatar, and relatively free movement across other parts of the country became permissible.

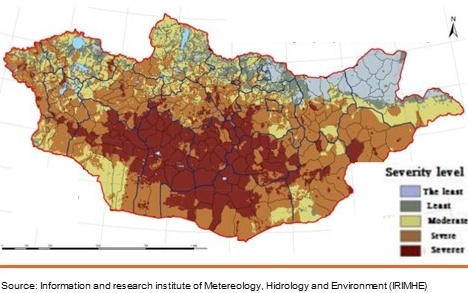

Each year, the Mongolian Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environmental Research compiles land and satellite data on droughts, dzuds and pastures. It then develops and issues a dzud risk map.

According to the map as of January 10, more than 20% of the country faced a very high dzud risk, while almost 60% was classified as at high risk and 15% as at moderate risk.

About 11.7mn heads of livestock herded by 26,600 households were forced to on to the winter migration, Monstame reported on December 29. Some herders had to migrate more than 700 kilometres to find better winter grazing lands, known as otor. Those who travelled the furthest actually left their home region as early as May; as a result, they could not allow their animals the usual mating period.

Amid the bitter cold, it is not unusual to hear of dedicated herder families keeping some of their animals inside their tents. Many livestock that have been unable to put on enough weight to survive the winter months are victims of rapid desertification caused by over-grazing and global warming that has over time degraded Mongolia’s land. Herders have as a consequence become more territorial. Some herders block other herders that want to let animals graze on their territory during the winter. The altercations this provokes have steadily gotten worse. In 2019, there were reports of herders killing one another over winter grazing disputes. Such reports are becoming commonplace in Mongolia.

Order not to expel

To help resolve the situation and to assist herders during the pandemic, the Mongolian State Emergency Commission and government advised provincial governors not to expel herders during the winter, but to provide moral support and cooperation. However, the herders have been informed that by government order they must return to their own land by April 1. This is a problem as livestock will in the coming weeks start to calve. If there is no vegetation, animals will be too weak to travel. But the government is aware of the issue and might adjust matters in response to the situation. Lawmaker Chinzorig Sodnom, who toured three provinces hit hard by the dzud in January, told local news outlet Zuunii Medee: “The herders voiced their concerns about high winter migration costs and rising fodder prices and on how they might not be able to travel back in April. Therefore, it is necessary to extend the implementation deadline of this law and provide more opportunities for these herders.”

Addressing the severity of this year’s dzud, with the help of the World Bank, the government since February 1 has provided Mongolian tugrik (MNT) 300,000 ($88) worth of fodder to each of the more than 45,000 herder households across the five provinces that have experienced the severest winter.

Heading to Ulaanbaatar

Suffering a lack of livestock, a substantial number of poverty-trapped nomadic herders—who rely on their animals for so much, from meat and milk, to the burning of their waste to heat their homes to selling their skins to buy food and pay children's education fees—have in recent times headed for Ulaanbaatar in search of economic prospects, but their lack of other job skills count against them.

The herders have generally settled in suburban areas of the capital known as "ger districts", which are largely slums with almost no public amenities and infrastructure, especially heating. During the winter months, the ger districts (a ger is a traditional yurt, or roundhouse) rely on coal for warmth. That makes Ulaanbaatar one of the most polluted cities in the world.

There is a backdrop of societal and economic change in Mongolia that has taken place since the 1990s, when the country became a democracy. The state stopped subsidising herders and the organisation that ran livestock population management was dissolved. Prior to Mongolia shifting away from the communist regime, the livestock head count never surpassed 25mn. In 2019, according to the national statistics office, it stood at 70.9mn.

This high number might stem from the introduced market economy and liberalisation of herding, but it is doubtful that herders are incentivised to keep a high number of animals because of actual market demand. The situation is more likely tied to fear—fear of suffering from a diminished number of livestock given the greater vulnerabilities now facing the nomadic herder.

The dzuds, the degradation of grazing land, the climate change causing desertification. Each of these growing woes interact with one another and it becomes more and more difficult to find sufficient sheltered lands with viable grazing. Keeping as much livestock as one can to survive the ever more treacherous steppes is grasped as a solution.

The prevailing perspective right now is that it seems many herders this winter escaped the bleak devastation of the dzud with swift action and some government intervention. The search for sustainable solutions, however, risks being overtaken by worsening events.

Only when the snows have melted will the full extent of the devastation become clear. Above, A young nomad pauses as he crosses a frozen stream. (Image: Taylor Weidman, The Vanishing Cultures Project, CC.Attrib.SA.3.0).

No comments:

Post a Comment