By Nicholas Barrett

BBC News

Chimneys at a coal-fired power station in Germany

The publication of a major report into climate change - warning of catastrophic consequences if the world does not act to limit global warming - has led to a renewed debate about what individual countries are doing.

British Conservative MP John Redwood said the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in November would not produce the desired results, unless other nations including China and the US did more to cut their carbon emissions.

And he had this to say about Germany on BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "It's only going to work if Germany, which puts out twice as much as we do, starts to take the issue seriously and closes down its coal power stations."

So, is he right?

What do the figures show?

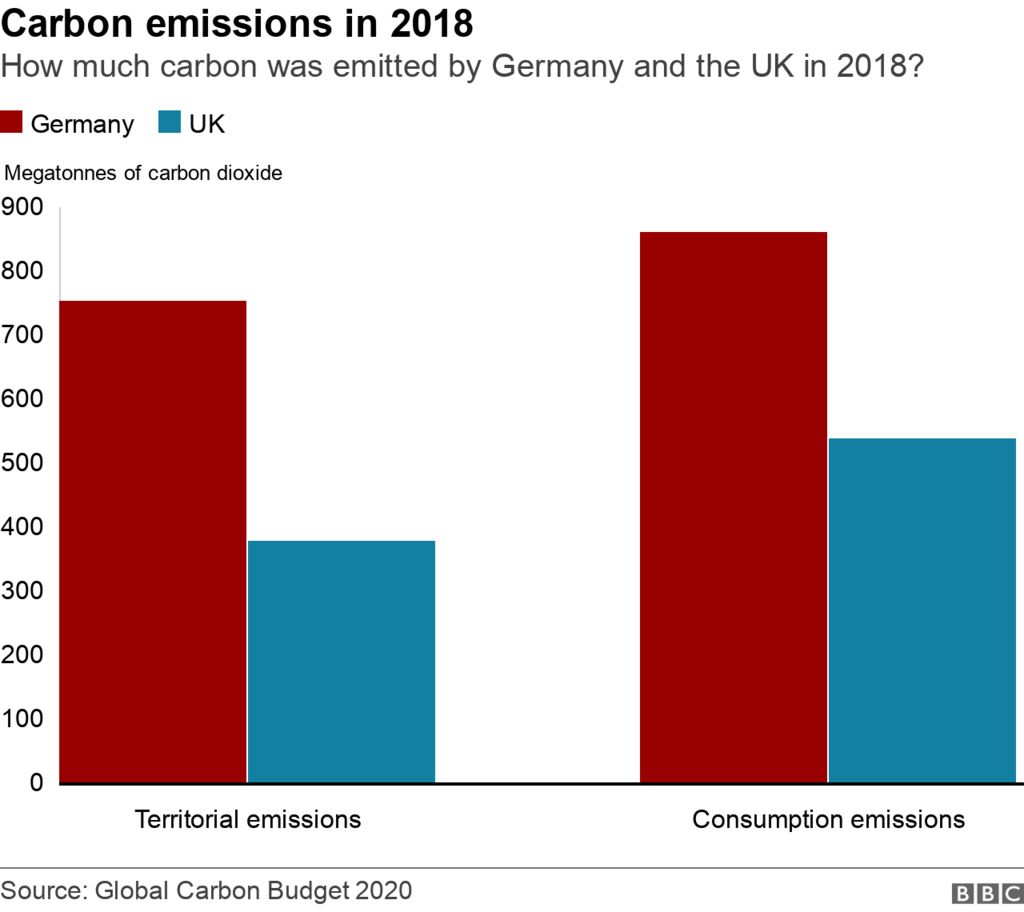

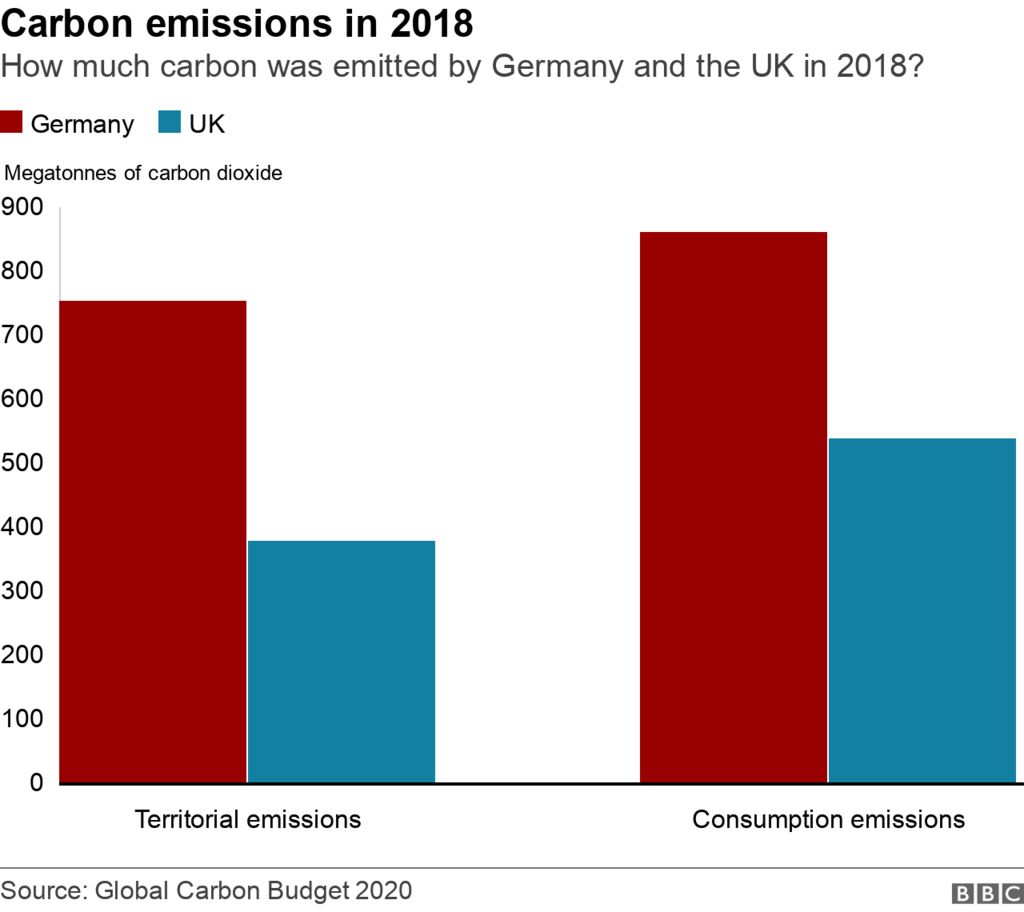

The Global Carbon Atlas (GCA) publishes emissions data from around the world. It says in 2018, the UK emitted 380 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO₂) from the burning of fossil fuels.

In the same year, Germany emitted 755 MtCO₂, about twice as much as the UK, and about 2% of the global total of 36,441 MtCO₂.

So the figures for 2018 support Mr Redwood's claim, but some context is needed when making this direct comparison.

Key differences

For a start, Germany is bigger than the UK. It's home to 83 million people, 17 million more than the UK.

It makes more things than the UK. Germany is a net exporter - meaning it exports more goods than it imports from other countries - whereas the UK is a net importer - meaning it imports more goods than it exports.

Speaking to the BBC, German Environment Minister Svenja Schulze said: "Germany is a strong industrial nation. We produce and export large numbers of goods that involve energy-intensive manufacturing processes. This makes the transition to a climate-neutral economy even more of a challenge."

Manufacturing accounts for twice as much of the economy in Germany as it does in the UK, according to the World Bank (23% of German national GDP, compared with just 11% in the UK).

"Germany has a larger population than the UK, so it's not too surprising total energy consumption and emissions are higher, because they have more residential and commercial buildings, and more cars on the road," says Dr Mike O'Sullivan, a mathematician and climate researcher at the University of Exeter, who collects data for the GCA.

There's also the question of which emissions you are measuring.

Territorial v consumption emissions

Climate scientists have two ways of measuring a country's carbon footprint:

Territorial emissions - this is how much CO2 is emitted within a country's borders. It takes no account of emissions generated elsewhere by the manufacture of imported goods.

Consumption emissions - this factors in emissions that come from the goods used or consumed in a country, including emissions from their production and delivery from abroad.

So, every time a car is manufactured in Germany and sold to a driver in Britain, the UK's consumption emissions increase, but its territorial emissions stay the same. The emissions from the factory that makes the car would count towards Germany's territorial emissions.

But once the car starts its engines in Britain, its emissions also count towards the UK's territorial emissions.

A total of 950,000 German-made cars were registered in the UK in 2016, according to the consultancy firm Deloitte.

By measuring consumption emissions, experts can better understand how responsible a country is for emissions produced abroad (for example, by another country making the goods which it is importing).

On this measure, the gap between the UK and Germany appears smaller.

We asked Dr O'Sullivan to calculate the difference.

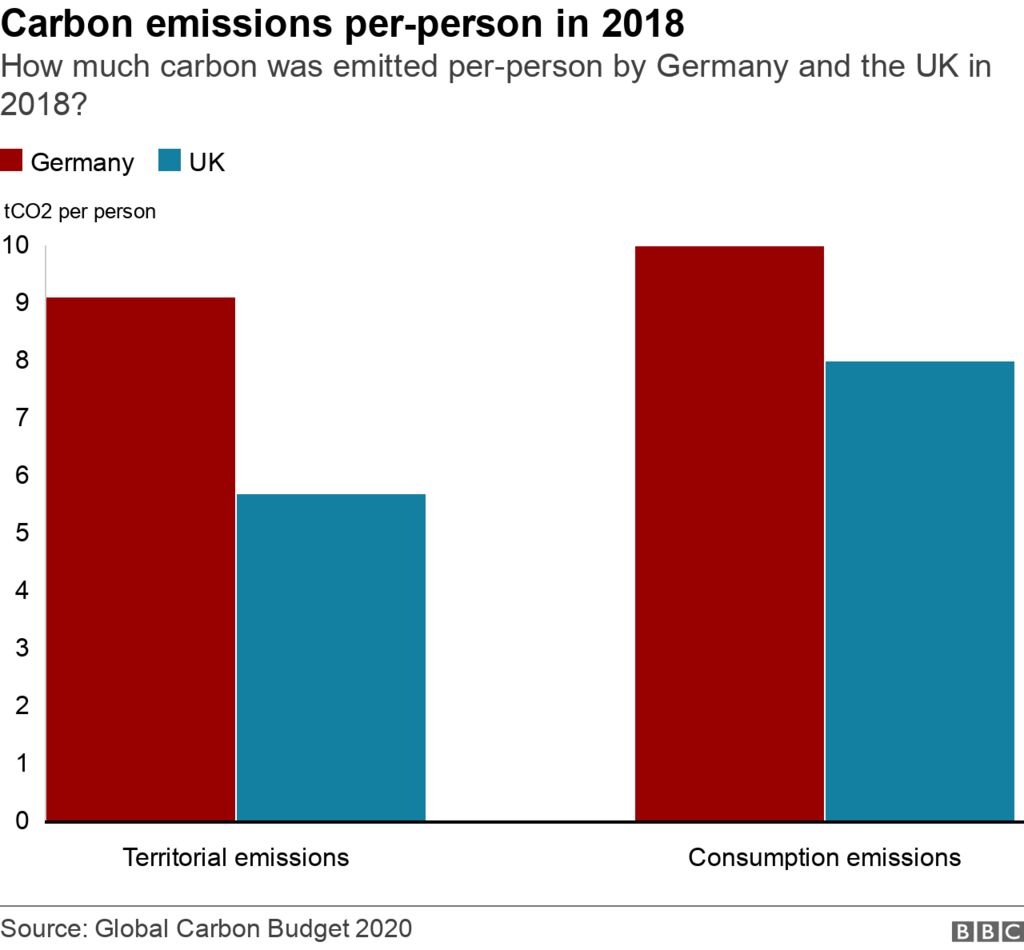

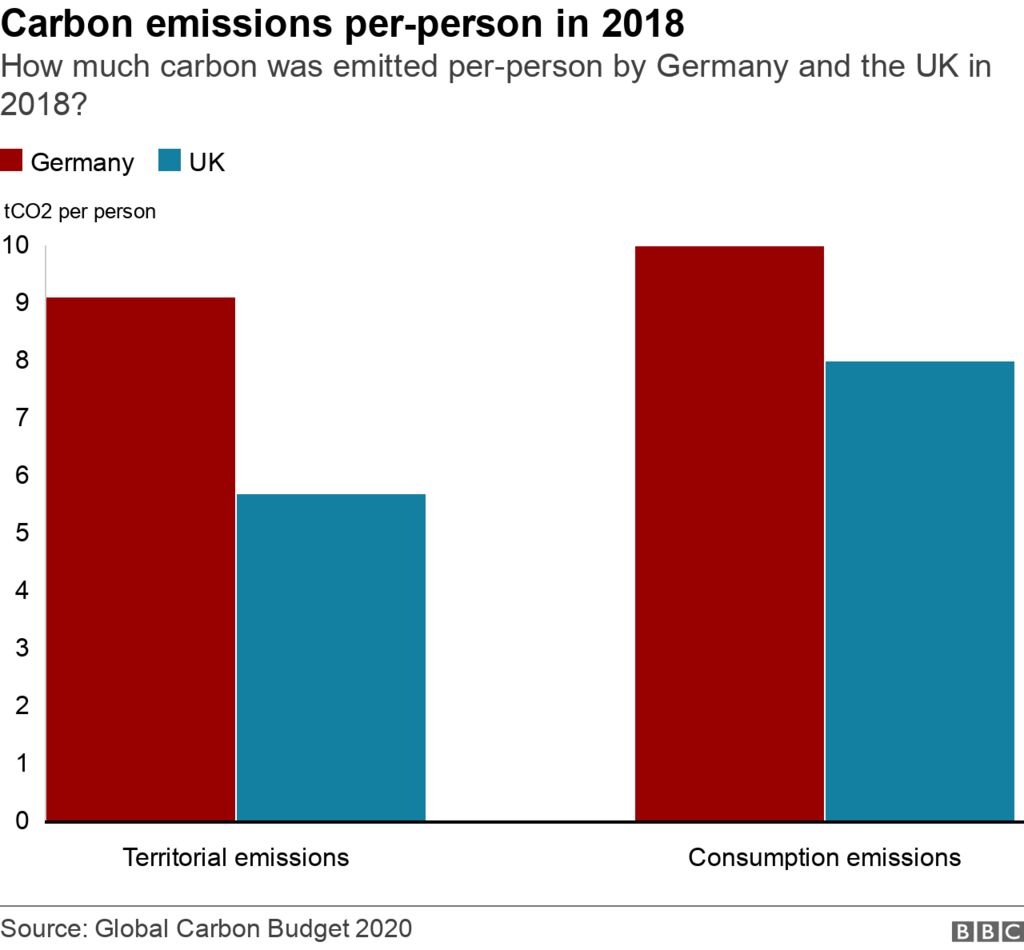

"If we account for population size and traded goods, the UK's emissions in 2018 were eight tonnes of CO2 per person, compared with 10 tonnes of CO2 per person for Germany, so 20% lower, not 50%."

Some have criticised the UK - and other countries - for focusing on territorial emissions. These are the basis for the UK's net-zero target and also what countries are required to submit to the United Nations.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg has accused the government of "creative carbon accounting".

The publication of a major report into climate change - warning of catastrophic consequences if the world does not act to limit global warming - has led to a renewed debate about what individual countries are doing.

British Conservative MP John Redwood said the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in November would not produce the desired results, unless other nations including China and the US did more to cut their carbon emissions.

And he had this to say about Germany on BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "It's only going to work if Germany, which puts out twice as much as we do, starts to take the issue seriously and closes down its coal power stations."

So, is he right?

What do the figures show?

The Global Carbon Atlas (GCA) publishes emissions data from around the world. It says in 2018, the UK emitted 380 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO₂) from the burning of fossil fuels.

In the same year, Germany emitted 755 MtCO₂, about twice as much as the UK, and about 2% of the global total of 36,441 MtCO₂.

So the figures for 2018 support Mr Redwood's claim, but some context is needed when making this direct comparison.

Key differences

For a start, Germany is bigger than the UK. It's home to 83 million people, 17 million more than the UK.

It makes more things than the UK. Germany is a net exporter - meaning it exports more goods than it imports from other countries - whereas the UK is a net importer - meaning it imports more goods than it exports.

Speaking to the BBC, German Environment Minister Svenja Schulze said: "Germany is a strong industrial nation. We produce and export large numbers of goods that involve energy-intensive manufacturing processes. This makes the transition to a climate-neutral economy even more of a challenge."

Manufacturing accounts for twice as much of the economy in Germany as it does in the UK, according to the World Bank (23% of German national GDP, compared with just 11% in the UK).

"Germany has a larger population than the UK, so it's not too surprising total energy consumption and emissions are higher, because they have more residential and commercial buildings, and more cars on the road," says Dr Mike O'Sullivan, a mathematician and climate researcher at the University of Exeter, who collects data for the GCA.

There's also the question of which emissions you are measuring.

Territorial v consumption emissions

Climate scientists have two ways of measuring a country's carbon footprint:

Territorial emissions - this is how much CO2 is emitted within a country's borders. It takes no account of emissions generated elsewhere by the manufacture of imported goods.

Consumption emissions - this factors in emissions that come from the goods used or consumed in a country, including emissions from their production and delivery from abroad.

So, every time a car is manufactured in Germany and sold to a driver in Britain, the UK's consumption emissions increase, but its territorial emissions stay the same. The emissions from the factory that makes the car would count towards Germany's territorial emissions.

But once the car starts its engines in Britain, its emissions also count towards the UK's territorial emissions.

A total of 950,000 German-made cars were registered in the UK in 2016, according to the consultancy firm Deloitte.

By measuring consumption emissions, experts can better understand how responsible a country is for emissions produced abroad (for example, by another country making the goods which it is importing).

On this measure, the gap between the UK and Germany appears smaller.

We asked Dr O'Sullivan to calculate the difference.

"If we account for population size and traded goods, the UK's emissions in 2018 were eight tonnes of CO2 per person, compared with 10 tonnes of CO2 per person for Germany, so 20% lower, not 50%."

Some have criticised the UK - and other countries - for focusing on territorial emissions. These are the basis for the UK's net-zero target and also what countries are required to submit to the United Nations.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg has accused the government of "creative carbon accounting".

Do governments meet their green targets?

"They're falling short by not considering the full scope of how to reduce emissions both inside and outside the UK," argues John Barrett, a professor in energy and climate policy at the University of Leeds.

"We need to consider how we could reduce the impact of what we consume, irrespective of whether it was made in the UK or not."

BBC Reality Check explains how to cut your carbon footprint

When asked about the focus on territorial emissions, a government spokesperson told us: "Our emissions have fallen by 44% since 1990, the fastest of any country in the G7 [group of the biggest economies]".

What about coal?

The UK has moved significantly faster to reduce its dependency on coal than Germany.

According to the Fraunhofer Research Institute, Germany generated 24.1% of its power from coal last year, while the UK was down to just 3.1%, data from the National Grid shows.

Germany is currently planning to phase out the use of coal for the production of electricity by 2038, while the British government has promised to close the UK's last coal power station before October 2024.

"Unlike the UK, Germany was heavily reliant on coal for far too long and started phasing out coal too late. Our goal is a sustainable, reliable and climate-friendly energy supply" says Ms Schulze.

In 2019, the UK passed a law requiring the government to bring territorial emissions down to net-zero emissions by 2050. Germany has

No comments:

Post a Comment