Paleontologists examined the braincases of two daspletosaurs and were surprised to find significant differences between them.

By

Isaac Schultz

Today 2:30PM

A mounted daspletosaur at the Canadian Museum of Nature.

Not much is known about Daspletosaurus, a late Cretaceous theropod that thrived in the forests of North America 75 million years ago. Now, paleontologists have shined a literal light on one of the animal’s mysteries, by taking CT scans of two of dinosaur braincases to digitally reconstruct the brains and adjacent structures.

Daspletosaurus was a meat-eating dinosaur first described in 1970; it is a tyrannosaur, meaning it’s part of the family Tyrannosauridae, the group that includes Tarbosaurus, Albertosaurus, and of course Tyrannosaurus rex, among other similarly terrifying predators. The research team looked at two Daspletosaurus skulls—one found near Alberta, Canada’s Red Deer river in 1921 and another dug up near the province’s Milk River at the turn of the millennium.

The two specimens are about 2 million years apart, a blink of the eye in terms of dinosaur evolution. At over 70 million years old, they’re far too ancient for any soft tissue to remain intact. But CT scans aren’t just great for peering non-invasively into complex structures like the brain—they can even be useful when the brain is long gone. In this case, the research team was able to map out some otherwise hidden structures in the two skulls that offer glimpses at how the dinosaurs made sense of their environment. Their work, published today in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, found differences between the animals’ braincases, suggesting that tyrannosaur skulls may have had more variation than previously thought.

Compared to other anatomical structures influenced by natural selection, “the brain is a very conservative organ … the bones surrounding it are also considered to change little,” said Tetsuto Miyashita, a paleontologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature and the study’s lead author, in an email.

“This was thought true to dinosaurs, but because we used to have access to so few braincases, we are only finding out recently in tyrannosaurs that the braincase actually varies a lot from species to species, or even within a species,” Miyashita expalined.

That’s a big takeaway from the recent study: that, based on the shapes of the two skulls and their respective ear structures, braincases, and dimensions, the animals may represent two distinct species, which would be a first for daspletosaurs. (The braincase is the specific part of the skull that holds the brain; it therefore offers unique insights on how dinosaurs’ nerves and senses worked.)

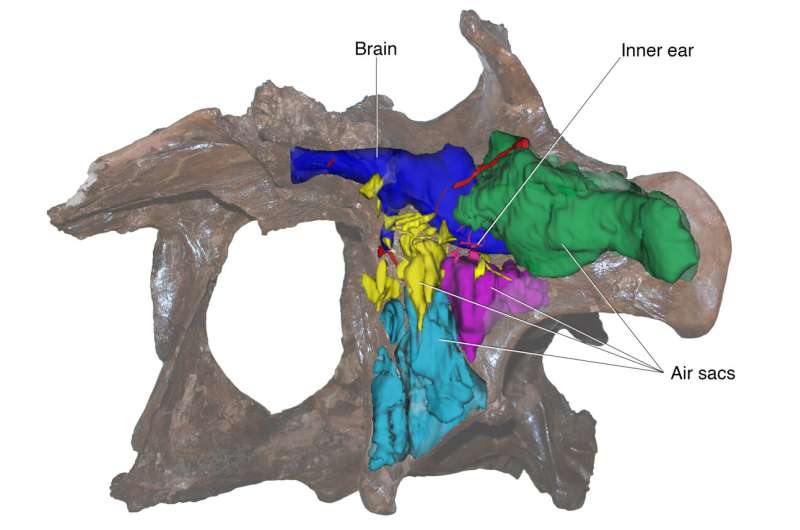

A diagram of some internal structures in one daspletosaur’s braincase.

In the paper, the researchers describe Daspletosaurus (specifically Daspletosaurus torosus) as a bit of a fallback classification for tyrannosaurs from western North America that aren’t clearly an animal like Albertosaurus or T. rex. As a result, daspletosaurs crop up over an “unusually broad” swath of the continent, the researchers wrote in the paper, though more recent work has begun to sift through these mislabeled creatures.

The new work follows up on studies clarifying the species of Daspletosaurus; Miyashita and his colleagues spent hundreds of hours scanning the internal spaces within the two fossils, which belonged to animals that lived in the late Cretaceous. With a unique view into their heads, the team found canals that hosted nerve bundles connected to the dinosaurs’ eyes. They also spotted air sacs—a common feature in theropods and modern birds—in many of the braincase bones.

“Cavities within the bones not only make the huge skull lighter but also are related to the middle region of the ear. The cavities probably helped to amplify sound and assist the system that communicates to the left and right ears, allowing the brain to determine where a sound is coming from,” said Ariana Paulina Carabajal, a paleontologist specializing in dinosaur braincases at the National University of Comahue in Argentina and a co-author of the paper, in a press release.

Though both fossils had these features, they varied, with one of the specimens having unique-looking sinuses and some internal characteristics more evocative of other tyrannosaur species, like Gorgosaurus and Bistahieversor. Miyashita said the work was just the first step in teasing apart the specimens long thought to be a single species, Daspletosaurus torosus. Next, the team will check out the rest of the body of the more recently discovered Daspletosaurus. We could have a new meat-eating dinosaur on our hands quite soon.

More: Utah Mass Death Site Bolsters Theory That Tyrannosaurs Hunted in Packs

Study of tyrannosaur braincases shows more variation than previously thought

Among the fierce carnivores that lived during the late Cretaceous was a predator named Daspletosaurus. The massive tyrannosaur, about nine meters long, lived in the coastal forest of what is now Alberta around 75 million years ago—-preceding the more famous T. rex by about 10 million years.

For the first time, scientists in Canada and Argentina have used CT scans to digitally reconstruct the brain, inner ear, and surrounding bones (known as the braincase) of two well-preserved Daspletosaurus specimens.

Their results, published online today in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, counter a prevailing view that dinosaur brains and the bones enclosing and protecting them varied little within species, or among closely related species, especially when compared with changes observed in other parts of the skeleton. "Our study with the two Daspletosaurus specimens suggests otherwise," explains Dr. Tetsuto Miyashita, paleontologist with the Canadian Museum of Nature and senior author of the study.

"We know that tyrannosaurs had relatively good-sized brains for a dinosaur, and this study shows that this pattern holds for Daspletosaurus. Furthermore, based on the shapes of the brain, ear structure, and braincase, we suggest that these two specimens represent distinct species of daspletosaurs."

Access to a braincase, the internal part of the skull that surrounds and protects the brain, helps unlock one of the most complex parts of dinosaur anatomy. This requires advanced medical technology such as a CT scanner to image the internal spaces hidden underneath thick bones, with the resulting hundreds of hours of work to reconstruct the brain and other fleshy parts slice by slice. Therefore, most studies on dinosaur brains have each focused on one specimen from a representative species of the group. As an exception, Tyrannosaurus rex has several such reconstructions of their brains. Now, this new study investigates two remarkably well-preserved skulls of Daspletosaurus, a much rarer tyrannosaur than T. rex.

One belongs to the original specimen of Daspletosaurus, which is prominently displayed at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Unearthed in 1921 along the banks of Alberta's Red Deer River, its description in 1970 as Daspletosaurus torosus ("muscular frightful lizard)" by Dr. Dale Russell ushered in the modern era of research on tyrannosaurids. The second specimen, uncovered in 2001, is with the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta. Miyashita is continuing to study it with Dr. Philip Currie of the University of Alberta, another author of the study.

Study of the braincase structure and its endocranial cavity provides insights on the brain itself, as well as characteristics such as the layout of cranial nerves, and some aspects of the sensory biology such as auditory and visual anatomy that drove the life of the dinosaur.

Dr. Ariana Paulina Carabajal, a dinosaur braincase expert in Argentina and study co-author at the Instituto de Investigaciones en Biodiversidad y Medioambiente (CONICET-Universidad Nacional del Comahue), provided the detailed models of the brain and inner ear anatomy and related structures. Among the findings were the presence of large bony canals that would have transmitted thick nerve bundles that moved the eyeballs. The researchers also describe large air sacs that filled up most of the braincase bones, which is in line with the limited studies known of other tyrannosaurs.

"These cavities within the bones not only make the huge skull lighter, but also are related to the middle region of the ear," explains Paulina Carabajal. "The cavities probably helped to amplify sound and assist the system that communicates to the left and right ears, allowing the brain to determine where a sound is coming from."

Yet, even within the two braincases of Daspletosaurus, there were differences. "It was surprising to see so many variations in the braincases even though the skeletons are similar," says Miyashita, who offers that their study provides a good reason to look at more braincases within similar groups of dinosaurs, or even within species.

"Researchers have looked inside so few braincases in dinosaurs, typically one each for whatever species they studied, that this reinforced the assumption that these structures don't change much within and among species. We just haven't looked inside enough skulls to document variation."

New evidence for combat and cannibalism in tyrannosaurs

More information: Ariana Paulina Carabajal et al, Two braincases of Daspletosaurus (Theropoda: Tyrannosauridae): anatomy and comparison, Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences (2021). DOI: 10.1139/cjes-2020-0185

Journal information: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences

Provided by Canadian Museum of Nature

No comments:

Post a Comment