Suhauna Hussain

Wed, May 15, 2024

A study by researchers at Harvard and UC San Francisco found that 91% of California service sector workers surveyed experienced at least one labor violation in the last year at work. (Los Angeles Times)

Although California has some of the toughest labor laws in the country, a new study has found workers routinely suffer violations while on the job.

A team of researchers from UC San Francisco and Harvard University earlier this year surveyed 980 California workers at dozens of the state's largest retail, food and other service sector companies. The workers reported frequent abuses over pay, work schedules and other issues.

The study found, for example, that 41% of the workers surveyed had experienced at least one serious violation of federal labor in the last year, such as being required to work off the clock, not being paid overtime, or being paid less than minimum wage, according to the report, which was released this week.

Violations around paid sick leave and meal breaks were also common, the researchers found. More than half of workers, 58%, were not given proper rest breaks.

All told, 91% of the workers surveyed experienced at least one violation in the last year, the study found.

The findings seemed at odds with the fact that California has led the way in raising labor standards, said one of the study’s authors, Daniel Schneider, a professor of social policy and sociology at Harvard He and his co-author, Kristen Harknett, a UCSF sociology professor, wanted to understand why the state's rigorous laws weren't doing more to protect workers from abuse.

The survey of workers, Schneider said, showed it was common for workers not to report problems. Many, he said, "have been robbed of their time and their wages and the vast majority do not come forward.”

Schneider said the study found that workers who came forward to report problems to someone inside their company were often met with retaliation or other negative consequences, and that workers are unlikely to seek help from regulatory bodies such as the state labor commissioner.

"This is not to say that the laws are ineffective, but that their full promise isn't realized when they are being violated so routinely," Schneider said. "We need a robust system of enforcement to ensure these labor laws are being enforced and complied with.”

The results of the new study come against the backdrop of renewed debate over a controversial California law known as the Private Attorneys General Act that gives workers the right to file lawsuits against their employers over back wages and to seek civil penalties on behalf of themselves, other employees and the state of California.

Read more: The battle brewing over California workers' unique right to sue their bosses

An initiative seeking to gut the act will appear on the ballot in November, the culmination of a long-running effort by business groups to scrap it.

Backers of the ballot initiative argue the law has resulted in a slew of lawsuits that small businesses and nonprofits have little ability to fight, and say that the long, costly lawsuits workers must pursue result in their getting less money than if they had filed complaints through state agencies.

Although not an expert on the law, Schneider said he believes there should be "more avenues for workers to come forward, to pursue some kind of redress, not fewer.”

The recent study is limited in scope, Schneider said, and does not capture the experiences of undocumented workers or those in domestic, agricultural and construction jobs where violations may be even more common.

Since the survey focused on workers at large firms, it leaves out service sector workers employed at smaller firms, which also likely experience violations at higher rates, he said.

Another study published this month by researchers at Rutgers University found that minimum wage violations have more than doubled in some major metro areas in California since 2014.

Workers in the Los Angeles, San Jose and San Diego metro areas who had been paid below minimum wage lost on average about 20% of the money they were owed, or as much as $4,000 a year, the study found.

In the San Francisco area, losses were even more steep, with workers losing an average of $4,300 to $4,900 annually to minimum wage violations, according to the study.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

California sees a surge in minimum wage violations

Jonathan Williams

Tue, May 14, 2024

Scroll back up to restore default view.

Minimum wage violations have more than doubled in California cities like Los Angeles, costing workers billions.

California workers lose up to $4,000 per year in major metro areas that include San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose, according to a study by Rutgers University.

“This is the time to be strengthening — not weakening — labor enforcement,” said Professor Janice Fine, director of the Workplace Justice Lab at Rutgers University.

The study was conducted by the School of Management and Labor Relations (SMLR), a research center dedicated to analyzing labor standards enforcement in the U.S.

“California is leading the way nationally in terms of strong state and local minimum wage laws, but our study shows that too many low-wage workers are not receiving the pay they are entitled to,” Fine said.

This November, a vote could come in the form of a California ballot initiative to repeal the Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA) act, revoking the ability to file class-action lawsuits over certain violations.

Instead of raising prices, California fast food restaurants should do this, franchisee says

Enacted in 2004, the California law empowers employees to file lawsuits for labor code violations on behalf of themselves, other workers, and the state.

The center took federal data collected from 2014 to 2023 and found that last year saw a 56% increase in violations, affecting nearly 1.5 million workers.

The study also found that mostly Black and Latino workers, and young people from the ages of 16-24 were more likely to experience minimum wage theft.

The most noticeable violation involved groups such as childcare workers, nannies, and home health care professionals.

On April 1, Californians experienced the fast-food minimum wage hike from $16 to $20 as the state continues to have one of the highest minimum wages in the country.

Business and labor groups would need to arrive at a deal before the end-of-June deadline to remove the measure. If no deal is reached, the issue will be presented to California voters in November.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

Labor laws largely exclude nannies. Some are banding together to protect themselves

CLAIRE SAVAGE and MORIAH BALINGIT

Updated Wed, May 15, 2024

Domestic Workers Rights

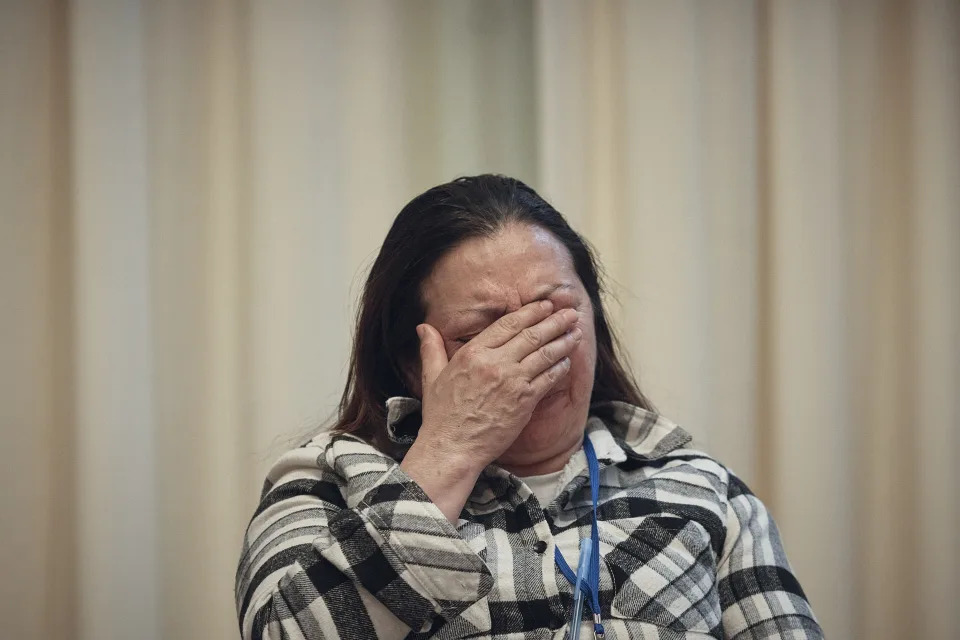

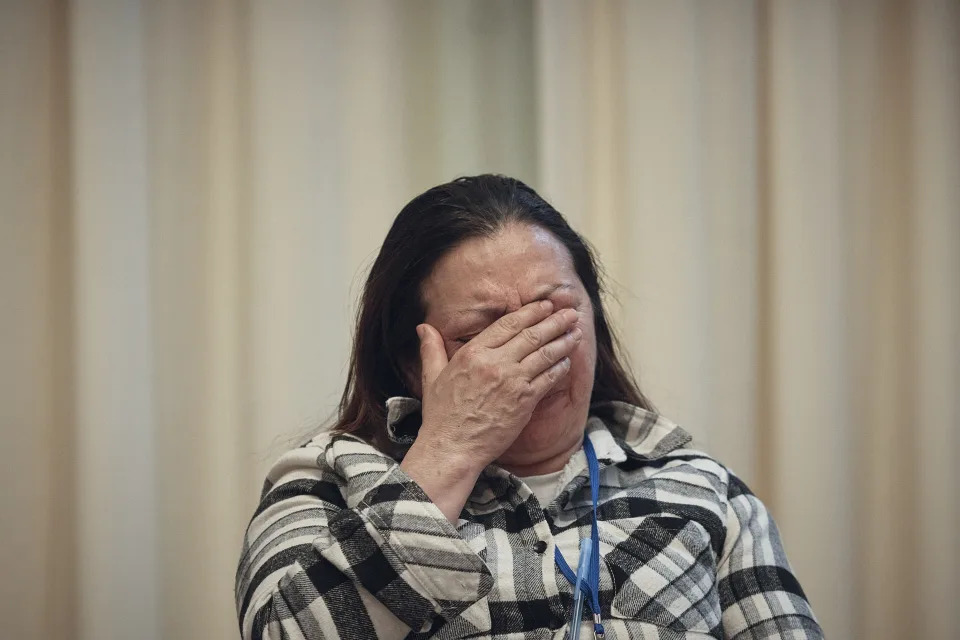

Sandra Milena Saenz cries during a sexual harassment prevention class for nannies and housekeepers on Saturday, April 27, 2024, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Nannies, housekeepers, and home care workers are excluded from many federal workplace protections in the United States, and the private, home-based nature of the work means abuse tends to happen behind closed doors.

NEW YORK (AP) — Map all doors in the home and figure out how to escape. Make a list of items in each room that you can use to defend yourself. Shelves, dishes, night stands, kitchen knives -- all can be weapons if you are attacked.

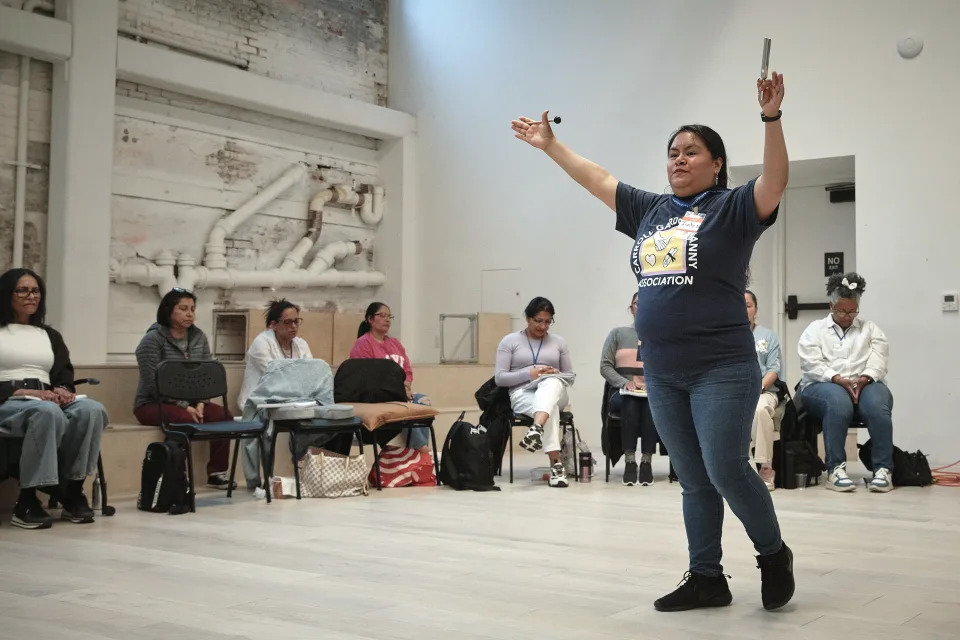

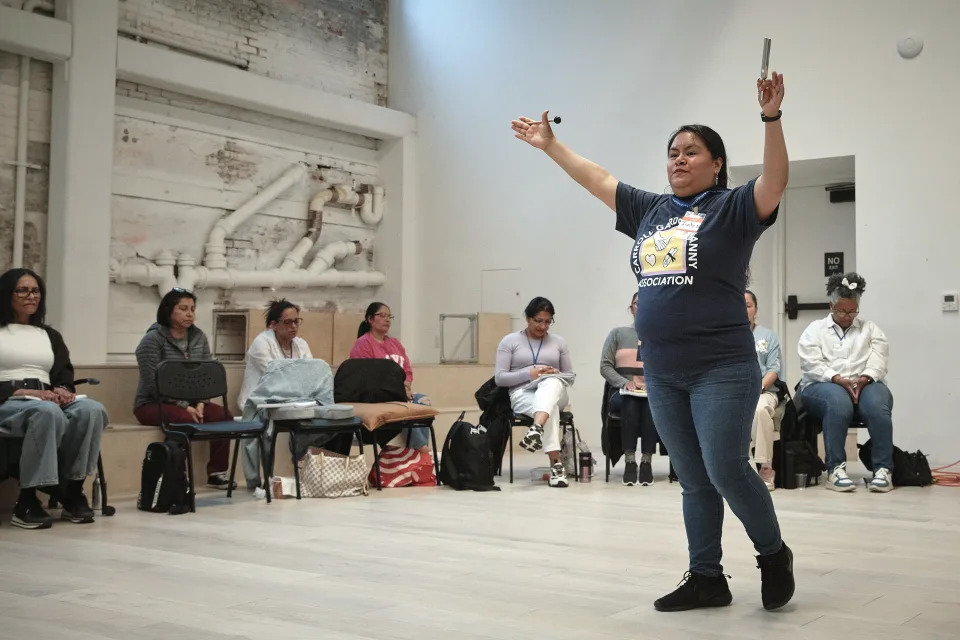

These are among the strategies Judith Bautista Hidalgo teaches her students -- 25 Hispanic women working as nannies, housekeepers and home care workers in the New York City area -- to defend themselves on the job. She hopes her April training on preventing sexual harassment will be a lifeline for many in the classroom who have experienced assault or abuse at work.

Domestic workers like those in Hidalgo's class are excluded from many federal workplace protections in the United States, and the private, home-based nature of the work means abuse tends to happen behind closed doors.

Although many domestic workers are covered under federal minimum wage and overtime laws, part-time and live-in workers are still exempt from some provisions. And domestic workers are generally excluded from Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — a federal law banning workplace discrimination, including sexual harassment — since it only applies to employers with 15 or more employees.

Neither are domestic workers covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which aims to ensure safe and healthy conditions for workers.

In the coming weeks, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) plans to introduce a national domestic workers bill of rights, which seeks to “reverse the historic exclusions of domestic workers from key labor laws,” according to a statement from her office.

Although previous efforts to pass similar legislation have stalled in Congress, support continues to mount this time around. But there are still plenty of hurdles to overcome, according to Ai-jen Poo, president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

“It’s not uncommon for a bill of the scope and significance to take decades,” she said.

Last month, domestic workers traveled to Washington, D.C., where they were in the crowd for a rally headlined by President Joe Biden. The next day, they met with Jayapal to discuss the federal domestic workers bill of rights, crowding onto couches and sharing their stories in English and Spanish.

Dulce Tovar, who has been a nanny for more than a decade, lives in El Paso, Texas, where neither the state nor the city have passed protections for domestic workers.

“There’s a lot of abuse,” Tovar said in Spanish. “If we complain about something, or ask for something, we aren’t heard. They tell us, ‘There’s a lot of people who want your job.’”

Part of the problem is that domestic work is undervalued and often dismissed as “caregiving work that women were just expected to do out of the goodness of their hearts” rather than professional work deserving of labor protections, said Julie Vogtman, senior counsel for the National Women’s Law Center.

Isabel Santos, a nanny from Chicago, said many do not appreciate the expertise experienced caretakers like herself bring. Santos, 51, has been caring for children for more than two decades and has received training on early childhood development. She has potty-trained children, taught them Spanish, taught them their alphabets and colors and has made sure they were ready for school by the time they entered kindergarten.

“To support the child’s development, we have to be a little bit teacher, a little bit nurse and a little bit psychologist,” Santos said.

Domestic workers from across the country have taken their fight beyond Congress and straight to statehouses, where they have been instrumental in getting labor protections passed.

But even in the 11 states with laws on the books that specifically target domestic workers, those often go unenforced. Women are more likely to be assaulted at work than men. Domestic workers, who make less than half of what a typical worker makes and are disproportionately women and immigrant women -- many of whom lack legal work status -- are especially vulnerable to workplace exploitation, experts say.

The women taking Hidalgo’s course as part of We Rise Nanny Training in Brooklyn have no intention of being defenseless.

“We are fighters. We matter,” said Aniuska Esther, a house cleaner who attended the course on a recent Saturday afternoon. “We do the work that no one else will do.”

A coalition of organizations including Carroll Gardens Nanny Association, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, and Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations created We Rise as a low-cost education and organizing program aimed at transforming the domestic worker industry. Besides combating sexual harassment, the curriculum offers classes in English and Spanish on workers’ rights, newborn care, CPR and first aid, organizing, negotiating, family communication, child nutrition and more.

Hidalgo herself knows firsthand what it feels like to endure sexual harassment in the workplace. Last April, she said she was cleaning an apartment in New Jersey when a friend of the employer visited. He later cornered her in the kitchen, exposed himself and started to masturbate.

When he advanced toward her despite her protests, Hidalgo said she pulled out a meat knife she had just washed and held it to his throat. “Stay away from me,” she repeated. He retreated to the living room and sat down “like nothing happened,” Hidalgo said.

She was fired after reporting the incident to her employer.

A year later she's still living with the consequences. Hugs from her boyfriend or teenage son send her into a panic. Crowded subways set her on edge. It's hard to fall asleep at night.

When she felt strong enough, she came forward with her case and began teaching sexual harassment prevention classes. Some participants came forward with their own experiences, and classmates engulfed them in hugs and offered tissues.

Some said they feel afraid to speak up because they lack legal work authorization. But “the same laws apply to an undocumented worker as any other worker,” said Laura Rodriguez, a New York City area employment attorney who primarily represents low-wage immigrant workers, including domestic workers.

Although employers may threaten to call immigration authorities if domestic workers speak up about problems in the workplace, they generally don't because they risk revealing that they broke the law themselves by hiring someone without work authorization, she explained.

Some clients Rodriguez has represented experienced abuses so severe they are considered labor trafficking violations. For example, when the pandemic hit, some families insisted their nannies remain at the employer’s home to avoid spreading Covid-19, so workers were unable to go out in public or see their own families for long periods at the risk of getting fired, according to Rodriguez.

On top of that, duties often increased -- cooking meals and doing laundry for the whole family instead of just the children after parents started working remotely, for example.

Combined with lower pay and job insecurity, “the pandemic was a nightmare for every domestic worker,” according to Wendy Guerrero, program and membership coordinator for Carroll Gardens Nanny Association and a former nanny who helped organize the We Rise Nanny Training.

Esther, the housekeeper who attended Hidalgo’s class, said the trainings make her feel empowered. Before she started taking the classes, Esther had to miss four days of work because of breast cysts requiring biopsies that left her arm and chest swollen for days. She didn't know that New York law entitled her to paid sick leave, and went without pay.

“I can defend myself now. I can’t stay silent. Now I feel that the law is with me and I feel that I can speak," she said.

____

Balingit reported from Washington, D.C.

___

The Associated Press’ women in the workforce and state government coverage receives financial support from Pivotal Ventures. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Although California has some of the toughest labor laws in the country, a new study has found workers routinely suffer violations while on the job.

A team of researchers from UC San Francisco and Harvard University earlier this year surveyed 980 California workers at dozens of the state's largest retail, food and other service sector companies. The workers reported frequent abuses over pay, work schedules and other issues.

The study found, for example, that 41% of the workers surveyed had experienced at least one serious violation of federal labor in the last year, such as being required to work off the clock, not being paid overtime, or being paid less than minimum wage, according to the report, which was released this week.

Violations around paid sick leave and meal breaks were also common, the researchers found. More than half of workers, 58%, were not given proper rest breaks.

All told, 91% of the workers surveyed experienced at least one violation in the last year, the study found.

The findings seemed at odds with the fact that California has led the way in raising labor standards, said one of the study’s authors, Daniel Schneider, a professor of social policy and sociology at Harvard He and his co-author, Kristen Harknett, a UCSF sociology professor, wanted to understand why the state's rigorous laws weren't doing more to protect workers from abuse.

The survey of workers, Schneider said, showed it was common for workers not to report problems. Many, he said, "have been robbed of their time and their wages and the vast majority do not come forward.”

Schneider said the study found that workers who came forward to report problems to someone inside their company were often met with retaliation or other negative consequences, and that workers are unlikely to seek help from regulatory bodies such as the state labor commissioner.

"This is not to say that the laws are ineffective, but that their full promise isn't realized when they are being violated so routinely," Schneider said. "We need a robust system of enforcement to ensure these labor laws are being enforced and complied with.”

The results of the new study come against the backdrop of renewed debate over a controversial California law known as the Private Attorneys General Act that gives workers the right to file lawsuits against their employers over back wages and to seek civil penalties on behalf of themselves, other employees and the state of California.

Read more: The battle brewing over California workers' unique right to sue their bosses

An initiative seeking to gut the act will appear on the ballot in November, the culmination of a long-running effort by business groups to scrap it.

Backers of the ballot initiative argue the law has resulted in a slew of lawsuits that small businesses and nonprofits have little ability to fight, and say that the long, costly lawsuits workers must pursue result in their getting less money than if they had filed complaints through state agencies.

Although not an expert on the law, Schneider said he believes there should be "more avenues for workers to come forward, to pursue some kind of redress, not fewer.”

The recent study is limited in scope, Schneider said, and does not capture the experiences of undocumented workers or those in domestic, agricultural and construction jobs where violations may be even more common.

Since the survey focused on workers at large firms, it leaves out service sector workers employed at smaller firms, which also likely experience violations at higher rates, he said.

Another study published this month by researchers at Rutgers University found that minimum wage violations have more than doubled in some major metro areas in California since 2014.

Workers in the Los Angeles, San Jose and San Diego metro areas who had been paid below minimum wage lost on average about 20% of the money they were owed, or as much as $4,000 a year, the study found.

In the San Francisco area, losses were even more steep, with workers losing an average of $4,300 to $4,900 annually to minimum wage violations, according to the study.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

California sees a surge in minimum wage violations

Jonathan Williams

Tue, May 14, 2024

Scroll back up to restore default view.

Minimum wage violations have more than doubled in California cities like Los Angeles, costing workers billions.

California workers lose up to $4,000 per year in major metro areas that include San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose, according to a study by Rutgers University.

“This is the time to be strengthening — not weakening — labor enforcement,” said Professor Janice Fine, director of the Workplace Justice Lab at Rutgers University.

The study was conducted by the School of Management and Labor Relations (SMLR), a research center dedicated to analyzing labor standards enforcement in the U.S.

“California is leading the way nationally in terms of strong state and local minimum wage laws, but our study shows that too many low-wage workers are not receiving the pay they are entitled to,” Fine said.

This November, a vote could come in the form of a California ballot initiative to repeal the Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA) act, revoking the ability to file class-action lawsuits over certain violations.

Instead of raising prices, California fast food restaurants should do this, franchisee says

Enacted in 2004, the California law empowers employees to file lawsuits for labor code violations on behalf of themselves, other workers, and the state.

The center took federal data collected from 2014 to 2023 and found that last year saw a 56% increase in violations, affecting nearly 1.5 million workers.

The study also found that mostly Black and Latino workers, and young people from the ages of 16-24 were more likely to experience minimum wage theft.

The most noticeable violation involved groups such as childcare workers, nannies, and home health care professionals.

On April 1, Californians experienced the fast-food minimum wage hike from $16 to $20 as the state continues to have one of the highest minimum wages in the country.

Business and labor groups would need to arrive at a deal before the end-of-June deadline to remove the measure. If no deal is reached, the issue will be presented to California voters in November.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

Labor laws largely exclude nannies. Some are banding together to protect themselves

CLAIRE SAVAGE and MORIAH BALINGIT

Updated Wed, May 15, 2024

Domestic Workers Rights

Sandra Milena Saenz cries during a sexual harassment prevention class for nannies and housekeepers on Saturday, April 27, 2024, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Nannies, housekeepers, and home care workers are excluded from many federal workplace protections in the United States, and the private, home-based nature of the work means abuse tends to happen behind closed doors.

(AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

NEW YORK (AP) — Map all doors in the home and figure out how to escape. Make a list of items in each room that you can use to defend yourself. Shelves, dishes, night stands, kitchen knives -- all can be weapons if you are attacked.

These are among the strategies Judith Bautista Hidalgo teaches her students -- 25 Hispanic women working as nannies, housekeepers and home care workers in the New York City area -- to defend themselves on the job. She hopes her April training on preventing sexual harassment will be a lifeline for many in the classroom who have experienced assault or abuse at work.

Domestic workers like those in Hidalgo's class are excluded from many federal workplace protections in the United States, and the private, home-based nature of the work means abuse tends to happen behind closed doors.

Although many domestic workers are covered under federal minimum wage and overtime laws, part-time and live-in workers are still exempt from some provisions. And domestic workers are generally excluded from Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — a federal law banning workplace discrimination, including sexual harassment — since it only applies to employers with 15 or more employees.

Neither are domestic workers covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which aims to ensure safe and healthy conditions for workers.

In the coming weeks, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) plans to introduce a national domestic workers bill of rights, which seeks to “reverse the historic exclusions of domestic workers from key labor laws,” according to a statement from her office.

Although previous efforts to pass similar legislation have stalled in Congress, support continues to mount this time around. But there are still plenty of hurdles to overcome, according to Ai-jen Poo, president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

“It’s not uncommon for a bill of the scope and significance to take decades,” she said.

Last month, domestic workers traveled to Washington, D.C., where they were in the crowd for a rally headlined by President Joe Biden. The next day, they met with Jayapal to discuss the federal domestic workers bill of rights, crowding onto couches and sharing their stories in English and Spanish.

Dulce Tovar, who has been a nanny for more than a decade, lives in El Paso, Texas, where neither the state nor the city have passed protections for domestic workers.

“There’s a lot of abuse,” Tovar said in Spanish. “If we complain about something, or ask for something, we aren’t heard. They tell us, ‘There’s a lot of people who want your job.’”

Part of the problem is that domestic work is undervalued and often dismissed as “caregiving work that women were just expected to do out of the goodness of their hearts” rather than professional work deserving of labor protections, said Julie Vogtman, senior counsel for the National Women’s Law Center.

Isabel Santos, a nanny from Chicago, said many do not appreciate the expertise experienced caretakers like herself bring. Santos, 51, has been caring for children for more than two decades and has received training on early childhood development. She has potty-trained children, taught them Spanish, taught them their alphabets and colors and has made sure they were ready for school by the time they entered kindergarten.

“To support the child’s development, we have to be a little bit teacher, a little bit nurse and a little bit psychologist,” Santos said.

Domestic workers from across the country have taken their fight beyond Congress and straight to statehouses, where they have been instrumental in getting labor protections passed.

But even in the 11 states with laws on the books that specifically target domestic workers, those often go unenforced. Women are more likely to be assaulted at work than men. Domestic workers, who make less than half of what a typical worker makes and are disproportionately women and immigrant women -- many of whom lack legal work status -- are especially vulnerable to workplace exploitation, experts say.

The women taking Hidalgo’s course as part of We Rise Nanny Training in Brooklyn have no intention of being defenseless.

“We are fighters. We matter,” said Aniuska Esther, a house cleaner who attended the course on a recent Saturday afternoon. “We do the work that no one else will do.”

A coalition of organizations including Carroll Gardens Nanny Association, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, and Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations created We Rise as a low-cost education and organizing program aimed at transforming the domestic worker industry. Besides combating sexual harassment, the curriculum offers classes in English and Spanish on workers’ rights, newborn care, CPR and first aid, organizing, negotiating, family communication, child nutrition and more.

Hidalgo herself knows firsthand what it feels like to endure sexual harassment in the workplace. Last April, she said she was cleaning an apartment in New Jersey when a friend of the employer visited. He later cornered her in the kitchen, exposed himself and started to masturbate.

When he advanced toward her despite her protests, Hidalgo said she pulled out a meat knife she had just washed and held it to his throat. “Stay away from me,” she repeated. He retreated to the living room and sat down “like nothing happened,” Hidalgo said.

She was fired after reporting the incident to her employer.

A year later she's still living with the consequences. Hugs from her boyfriend or teenage son send her into a panic. Crowded subways set her on edge. It's hard to fall asleep at night.

When she felt strong enough, she came forward with her case and began teaching sexual harassment prevention classes. Some participants came forward with their own experiences, and classmates engulfed them in hugs and offered tissues.

Some said they feel afraid to speak up because they lack legal work authorization. But “the same laws apply to an undocumented worker as any other worker,” said Laura Rodriguez, a New York City area employment attorney who primarily represents low-wage immigrant workers, including domestic workers.

Although employers may threaten to call immigration authorities if domestic workers speak up about problems in the workplace, they generally don't because they risk revealing that they broke the law themselves by hiring someone without work authorization, she explained.

Some clients Rodriguez has represented experienced abuses so severe they are considered labor trafficking violations. For example, when the pandemic hit, some families insisted their nannies remain at the employer’s home to avoid spreading Covid-19, so workers were unable to go out in public or see their own families for long periods at the risk of getting fired, according to Rodriguez.

On top of that, duties often increased -- cooking meals and doing laundry for the whole family instead of just the children after parents started working remotely, for example.

Combined with lower pay and job insecurity, “the pandemic was a nightmare for every domestic worker,” according to Wendy Guerrero, program and membership coordinator for Carroll Gardens Nanny Association and a former nanny who helped organize the We Rise Nanny Training.

Esther, the housekeeper who attended Hidalgo’s class, said the trainings make her feel empowered. Before she started taking the classes, Esther had to miss four days of work because of breast cysts requiring biopsies that left her arm and chest swollen for days. She didn't know that New York law entitled her to paid sick leave, and went without pay.

“I can defend myself now. I can’t stay silent. Now I feel that the law is with me and I feel that I can speak," she said.

____

Balingit reported from Washington, D.C.

___

The Associated Press’ women in the workforce and state government coverage receives financial support from Pivotal Ventures. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment