Gem Diamonds to cut jobs, salaries amid industry crisis

Cecilia Jamasmie | July 23, 2025 |

Letšeng diamond mine in Lesotho. (Image courtesy of Gem Diamonds.)

Gem Diamonds (LON: GEMD) has become the latest casualty in a deepening crisis engulfing the global diamond industry, announcing sweeping cost-cutting measures as the market buckles under falling prices and the growing popularity of lab-grown alternatives.

The Africa-focused diamond producer reported a 43% drop in revenue to $44.7 million for the first half of its financial year. Carat sales fell 22% to 44,360, while the average price per carat plunged 26% to $1,008.

In response,Gem Diamonds said it would reduce operating costs by $1.4 million to $1.6 million per month and cut around 250 jobs, or 20% of its workforce, at its Letšeng mine in Lesotho. Executives have also taken voluntary salary reductions.

“Considering the prolonged weakness in global diamond prices, compounded by a weak dollar and ongoing US tariff uncertainties, Gem has implemented decisive measures to conserve cash and protect shareholder value,” the company said.

Despite meeting production targets, Gem Diamonds admitted it has not been shielded from sustained pressure on rough diamond prices and adverse currency movements. Investors reacted accordingly, with the company’s shares falling more than 20% in early trading on the London Stock Exchange. They partially rebound to 5.5 pence in late trading, valuing the company at £7.7 million ($10 million).

Gem Diamonds’ measures mirrors those of its peers. just last week, Burgundy Diamond Mines (ASX: BDM) halted open pit operations at its Ekati mine in Canada’s Northwest Territories, triggering mass layoffs.

All three operating diamond mines in the region — Ekati, Diavik and Gahcho Kué — are now facing eventual closure, with Diavik scheduled to close in 2026 and Gahcho Kué expected to cease operations by 2030. Ekati’s long-term future remains uncertain.

Getting worse

Signs of a worsening crisis in the diamond sector were already clear in the first three months of 2025. De Beers, the world’s largest producer by value, saw a 44% drop in revenue in Q1 and is sitting on $2 billion in unsold inventory. It plans to cut over 1,000 jobs at its Debswana joint venture in Botswana.

Russia’s Alrosa, hampered by sanctions, reported a 77% plunge in profits and has halted production at key sites.

Petra Diamonds (LON: PDL) is fighting to survive after a 30% drop in sales and the sudden departure of its CEO.

Lucapa (ASX:LOM) entered voluntary administration in Australia, and Sierra Leone’s Koidu Limited shuttered operations and laid off more than 1,000 employees after losing $16 million to labour strikes.

Even Lucara (TSX: LUC), which operates in both Botswana and Canada, has flagged an “ongoing concern” risk despite hitting production records.

All eyes are now on De Beers. Once synonymous with manufactured scarcity and aggressive branding, the company is up for sale. Parent company Anglo American (LON: AAL) has cut its valuation by $4.5 billion in just over a year. No buyers have emerged, but Botswana is reportedly pushing to take a controlling stake.

Botswana seeks control of De Beers

Staff Writer | July 23, 2025 | 8:19 am Markets Top Companies Africa Europe Diamond

Image courtesy of De Beers.

Botswana is pushing to take a controlling stake in De Beers as Anglo American (LON: AAL) prepares to divest from the diamond company.

The country’s mining minister Bogolo Kenewendo told the Financial Times on Wednesday that President Duma Boko “remains resolute” in his quest to increase Botswana’s stake in De Beers to ensure Botswana’s full control over this strategic national asset and the entire value chain including marketing.

The comments come ahead of an early August deadline for bids to be submitted to Anglo from potential buyers of the diamonds business.

Kenewendo said any sale of the company “without our support will be difficult to achieve”.

“Our partners at Anglo American have, regrettably, failed to manage the process transparently or in co-ordination with the government and with our support,” she added.

De Beers, the world’s leading diamond producer by value, has been on the chopping block since May 2024, when Anglo announced plans to either sell the unit or launch an initial public offering (IPO). This decision came as part of a corporate overhaul triggered by Anglo’s successful defence against a £39 billion ($49 billion) takeover bid by Australian rival BHP (ASX: BHP).

The miner sources about 70% of its diamonds from the country.

The country’s bold move comes despite a widening budget deficit, expected to hit 7.5% by 2026, and analysts’ skepticism over its ability to raise sufficient funds. Kenewendo, however, insisted that “financing is not an issue.”

Shares of Anglo American rose 0.3% to close at £23.47 apiece in London on Wednesday, valuing the company at £27.6 billion.

Strategic asset, market slump

The developments pose a major challenge to Anglo’s “dual-track” strategy of either selling or publicly listing its 85% De Beers stake.

De Beers has struggled amid falling demand from China and growing competition from lab-grown stones. Anglo has twice cut De Beers’ valuation, most recently to $4.1 billion in February. The miner also reported a 44% revenue drop in the first quarter and is holding $2 billion in unsold diamonds.

Anglo said it remains in regular talks with Botswana and acknowledged the country’s role as a key partner.

Cecilia Jamasmie | July 23, 2025 |

Man-made diamonds are 100% carbon, with the same hardness and sparkle of the original.(Stock image: Motortion.)

De Beers, the world’s largest diamond miner by value, once convinced the world that true love needed a mined diamond. The precious stones weren’t just beautiful — they were a natural wonder, formed over billions of years deep within the Earth and extracted from far-off places by companies like De Beers itself.

That mystique guaranteed mine diamonds a century of dominance. Today, that power is fading fast as lab-grown diamonds, identical in structure, sparkle, and hardness, are redefining what a “real” diamond means.

These synthetic gems, created under high pressure and temperature in controlled environments, have gone from novelty to norm. They are widely available and increasingly affordable. And that’s rattling the foundations of a global industry.

Alarm bells

The central Chinese province of Henan now produces over 70% of the world’s lab-grown diamonds for jewellery. Many end up on the ring fingers of newly engaged couples, especially in the United States.

In 2022, Walmart began selling lab-made stones. Two years later, they made up half its diamond assortment. Sales surged 175% in 2024 compared to the previous year, making the retail giant the second-largest fine jewellery seller in the country, just behind Signet.

The rapid growth has triggered alarm among some traditional players. Yoram Dvash, president of the World Federation of Diamond Bourses says synthetic diamonds now dominate new US engagement rings. He warned of an “unprecedented flood” of lab-made stones and called on the industry to unite in response.

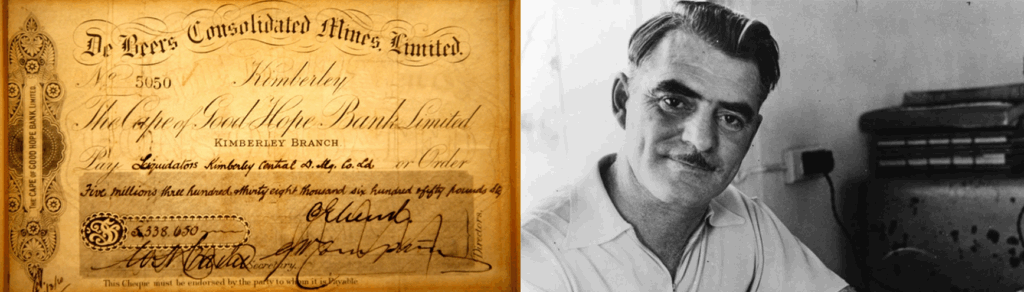

(Click on image to enlarge) LEFT: Competitors Cecil Rhodes and Barny Banato join forces, creating De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888. | RIGHT: Canadian geologist Dr. John Williamson sets up the Williamson mine in Tanzania, famous for its pink diamonds. (Images courtesy of De Beers Group.)

Not everyone sees an existential threat. Independent analyst Paul Zimnisky attributes the recent downturn to post-covid demand corrections, a luxury slowdown in China, and the disruptive ascent of lab diamonds. He remains cautiously optimistic, noting that lab-grown stones now account for over 20% of global diamond jewellery sales, up from under 1% in 2016.

For engagement rings, the market share is even higher. A 2024 survey of nearly 17,000 US couples by The Knot found that more than half of engagement rings featured a lab-made diamond, up 40% from 2019.

Zimnisky believes the industry’s survival hinges on branding. “If the industry gets lethargic and loses its way on the marketing front, all bets are off,” he told MINING.COM earlier this year.

Not everyone sees an existential threat. Independent analyst Paul Zimnisky attributes the recent downturn to post-covid demand corrections, a luxury slowdown in China, and the disruptive ascent of lab diamonds. He remains cautiously optimistic, noting that lab-grown stones now account for over 20% of global diamond jewellery sales, up from under 1% in 2016.

For engagement rings, the market share is even higher. A 2024 survey of nearly 17,000 US couples by The Knot found that more than half of engagement rings featured a lab-made diamond, up 40% from 2019.

Zimnisky believes the industry’s survival hinges on branding. “If the industry gets lethargic and loses its way on the marketing front, all bets are off,” he told MINING.COM earlier this year.

Marketing reset

The spotlight has shifted back to De Beers. Once the architect of diamond scarcity and prestige, it’s now for sale. Parent company Anglo American (LON: AAL) slashed its valuation by $4.5 billion in just over a year. While no buyer has stepped forward, Botswana is reportedly pushing to take a controlling stake.

De Beers’ troubles go beyond ownership uncertainty. To counter the effects of oversupply and waning demand, the company is mining fewer diamonds. Rough diamond production fell 26% in the first half of the year to 7.22 million carats. Anglo had already slashed its 2025 output forecast to as low as 20 million carats, down from an earlier target of up to 33 million.

In May, De Beers shut down its lab-grown diamond jewellery brand, Lightbox, in a clear move to recommit to natural stones. It’s betting that a focused narrative, one rooted in rarity and romance, can revive demand and stabilize mined diamond prices.

Making that case is harder than ever. Lab-grown diamonds are chemically identical to their natural counterparts. Even trained gemologists need specialized equipment to tell them apart. The core difference now lies not in composition, but in story.

Lab-grown diamonds may be more affordable and visually identical to natural ones, but they typically don’t hold their value. While mined diamonds can resell for 20% to 60% of their original retail price, lab-grown gems often fetch just 10% to 30%, sometimes even less.

In a recent interview with The Wall Street Journal, De Beers CEO Al Cook predicted that as lab-grown diamonds become more abundant, their value will continue to fall. He warned they risk being seen more like low-cost imitations such as cubic zirconia or moissanite, which have different chemical compositions and are easily recognized as fakes.

The Luanda Accord was signed in June to pool resources and boost global marketing efforts for natural diamonds. (Image courtesy of the Natural Diamond Council.)

For buyers who spent thousands on lab-created stones, Cook didn’t sugar-coat the outlook. “I weep for you,” he said.

To sway a younger, more value-conscious generation, the industry has turned to fresh campaigns. De Beers and Signet launched “Worth the Wait” in October 2024, targeting so-called Zillennials — those born between 1993 and 1998 — with messaging about milestones, meaning, and the uniqueness of natural diamonds.

In June, a coalition of producing countries and De Beers inked the Luanda Accord, pledging 1% of rough diamond revenues toward a marketing fund run by the Natural Diamond Council. The NDC has since rolled out a new short film series and an educational website aimed at helping retail staff better articulate the case for natural gems.

A previous campaign that branded lab-made stones as “dupes” and urged buyers to “swipe left” backfired and was taken down.

Changing values

Even as traditionalists double down, the cultural ground is shifting. Young buyers care about origin and ethics. They want proof their purchase doesn’t fund conflict or exploit workers. Danish retailer Pandora switched entirely to lab-made diamonds in 2021, citing environmental and social concerns as well as lower prices.

For buyers who spent thousands on lab-created stones, Cook didn’t sugar-coat the outlook. “I weep for you,” he said.

To sway a younger, more value-conscious generation, the industry has turned to fresh campaigns. De Beers and Signet launched “Worth the Wait” in October 2024, targeting so-called Zillennials — those born between 1993 and 1998 — with messaging about milestones, meaning, and the uniqueness of natural diamonds.

In June, a coalition of producing countries and De Beers inked the Luanda Accord, pledging 1% of rough diamond revenues toward a marketing fund run by the Natural Diamond Council. The NDC has since rolled out a new short film series and an educational website aimed at helping retail staff better articulate the case for natural gems.

A previous campaign that branded lab-made stones as “dupes” and urged buyers to “swipe left” backfired and was taken down.

Changing values

Even as traditionalists double down, the cultural ground is shifting. Young buyers care about origin and ethics. They want proof their purchase doesn’t fund conflict or exploit workers. Danish retailer Pandora switched entirely to lab-made diamonds in 2021, citing environmental and social concerns as well as lower prices.

Even experts need specialized equipment to tell the difference between quality lab-grown and mined diamonds. (Image courtesy of the Natural Diamond Council.)

Zimnisky notes that for economies “sensitive” to changes in the diamond market, such as Botswana, Canada, Namibia, Angola and Russia, the stakes are high. “This is a luxury product,” he said. “It needs to be merchandised as such. All stakeholders must contribute to shaping the message.”

The mystique of mined diamonds may be fading, but the desire for something meaningful remains. For the industry to stay relevant, it must shift from legacy to legitimacy, replacing old myths with modern values.

Zimnisky notes that for economies “sensitive” to changes in the diamond market, such as Botswana, Canada, Namibia, Angola and Russia, the stakes are high. “This is a luxury product,” he said. “It needs to be merchandised as such. All stakeholders must contribute to shaping the message.”

The mystique of mined diamonds may be fading, but the desire for something meaningful remains. For the industry to stay relevant, it must shift from legacy to legitimacy, replacing old myths with modern values.

No comments:

Post a Comment